Distal Femoral Physeal Fractures

Martin J. Herman

DEFINITION

Fractures of the distal femoral physis are those that involve the physis or growth plate of the distal femur.

These fractures occur most commonly in older children and adolescents from falls or sports activities.

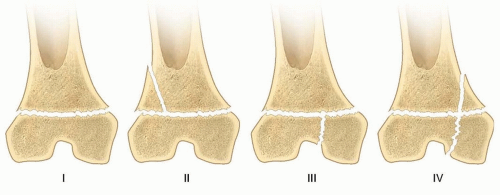

Physeal fractures of the distal femur are best categorized by the Salter-Harris (SH) classification. The vast majority of these fractures are SH type I and II fractures, which are extra-articular. SH III and IV fractures, which are uncommon, are intra-articular (FIG 1).3

The goals of treatment for these fractures are healing of the fracture in acceptable alignment and anatomic restoration of the physis and joint line to reduce the risk of growth arrest and premature arthritis of the knee.

ANATOMY

The distal femoral physis accounts for 40% of the longitudinal growth of the lower extremity, growing approximately 9 mm per year until skeletal maturity.

Morphologically, this growth plate is not flat but instead has undulations across its surface which add to the stability of the physis but also make it more prone to damage when fractures of the physis occur.

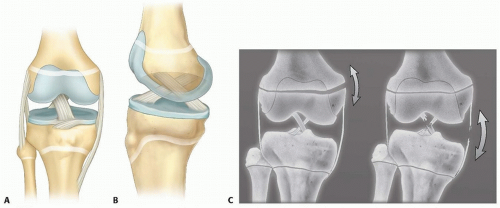

The medial and lateral collateral ligaments originate from the distal femoral epiphysis distal to the physis. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments originate from the intercondylar notch, also distal to the physis (FIG 2).

The popliteal artery courses along the posterior surface of the distal femur as its traverses the popliteal space. The sciatic nerve divides into the peroneal and posterior tibial branches just proximal to the physis. Anterior displacement of the distal fragment is associated with popliteal artery injury, and medial displacement is associated with peroneal nerve injury.

PATHOGENESIS

Physeal fractures generally cleave through the zone of hypertrophic calcification then go either proximal (SH I and II) or distal to this zone (SH III and IV). In distal femoral physeal fractures, however, the fracture cleaves not only through the hypertrophic zone but also crosses other zones including the germinal zone of the growth plate because of its undulating morphology, making growth disturbance likely even after SH I and II fractures.

These fractures result most commonly from medial or lateral forces applied to the knee, resulting in varus (medial) or valgus (lateral) displacement, respectively.

Knee hyperextension injuries lead to anteriorly displaced fractures while direct forces applied to the flexed knee, such as a dashboard strike during a motor vehicle crash, commonly cause intra-articular SH III and IV fractures.

NATURAL HISTORY

The distal femoral physis has tremendous healing and remodeling potential in children with at least 2 years of growth remaining. In this age group, fractures with anatomic realignment of the joint surface that are realigned with less than 10 degrees of deformity in the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral planes heal with restoration of normal function in most patients who do not develop a growth arrest.

For patients who develop a growth arrest, however, the results are variable. The growth disturbance is the result of either injury to the germinal cells of the physis from the trauma of the initial injury or subsequent reduction, from malreduction with physeal bar formation, or from iatrogenic injury from screws that cross the physis.1, 2, 6

The resulting problems related to growth disturbance are angular deformities from incomplete arrest or limb length discrepancy from complete physeal closure.

Because of the high risk of growth-related problems, patients and their families must be counseled at the time of initial treatment about the potential for complications.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A complete history includes an inquiry about the precise mechanism of injury and when it occurred, questions about changes in motor or sensory function of the affected limb, and any significant medical history.

A complete physical examination begins with inspection of the limb for deformity, swelling, knee joint effusion, excessive bleeding from an open injury, and any other defects of the soft tissue such as lacerations or abrasions. The entire limb is then palpated to identify focal areas of tenderness about the knee and any associated injuries proximal and distal to it.

A motor and sensory examination is necessary to identify neurologic deficits of the peroneal and posterior tibial nerves. The vascular status of the limb is assessed by assessing the distal pulses and other signs of limb perfusion including the capillary refill of the toes and the temperature of the limb.

In patients without obvious deformity but with a history and examination that is otherwise suspicious for a distal physeal fracture, gentle varus-valgus and anterior drawer or Lach-man stress testing may allow the examiner to differentiate between a physeal injury and a ligament injury.

IMAGING

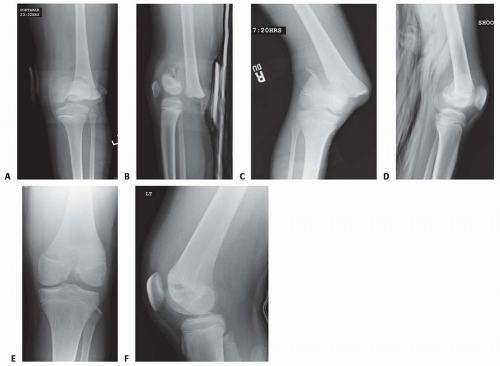

High-quality AP and lateral radiographs of the entire extremity are necessary to fully assess these injuries as well as the overall alignment of the limb and other associated fractures (FIG 3). Dedicated views of the knee, with comparison views of the uninjured side if necessary, are useful to precisely define the fracture pattern, especially when the fracture is nondisplaced.

Computed tomography (CT) of the knee is indicated for most intra-articular fractures (SH types III and IV) to define the fracture pattern and the degree of displacement as well as to aid in planning of fixation (FIG 4).5

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used to confirm occult fractures when the radiographs are normal but the examination is suspicious for a fracture as well as to diagnose other knee pathology such as meniscus tears, ligament tears, and osteochondral injuries.4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Distal femoral metaphyseal fracture

Knee (tibiofemoral) dislocation

Patellar dislocation

Proximal tibial fracture

Collateral ligament tears (vs. nondisplaced fracture)

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

Long-leg cast immobilization for 4 to 6 weeks is indicated only for fractures which are nondisplaced.

Fractures which require reduction to achieve satisfactory alignment are generally unstable and are best treated with fixation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications

Surgical reduction and fixation are indicated for all displaced distal femoral physeal fractures.

Surgical fixation is indicated for some nondisplaced fractures that are at high risk for displacement, such as SH III and IV fractures or those that are associated with severe soft tissue injury or neurovascular abnormalities. Other indications are obesity that inhibits effective long-leg cast immobilization and behavioral or intellectual problems that preclude cooperation with non-weight-bearing instructions.

FIG 3 • A,B. AP and lateral radiographs of displaced SH I distal femoral physeal fracture. C,D. AP and lateral radiographs of displaced SH II distal femoral physeal fracture. E,F. AP and lateral radiographs of a displaced SH III distal femoral physeal fracture.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|