Myofascial pain is one of the most common causes of pain. The diagnosis of myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) is made by muscle palpation. The source of the pain in MPS is the myofascial trigger point, a very localized region of tender, contracted muscle that is readily identified by palpation. The trigger point has well-described electrophysiologic properties and is associated with a derangement of the local biochemical milieu of the muscle. A proper diagnosis of MPS includes evaluation of muscle as a cause of pain, and assessment of associated conditions that have an impact on MPS.

Key points

- •

Myofascial pain is a common condition that occurs as a primary source of pain as well as a comorbid pain with other conditions.

- •

The source of pain in myofascial pain is the myofascial trigger point that is a small region of hardness and tenderness in a taut band of muscle.

- •

Many of the pain syndromes are caused by pain referred from the trigger point region.

- •

The diagnosis of myofascial pain in the clinical setting is best made by palpation of the trigger point, moving in a cross-fiber direction perpendicular to the direction of the fibers.

- •

Evaluation of the patient must include an assessment of those factors that either predispose the patient to the development of myofascial pain or that are comorbid with it.

Introduction

Myofascial pain (MP) is a widespread and universal cause of soft tissue pain. Physicians commonly overlook this condition because of lack of awareness and training but it is a relatively simple diagnosis. The central feature of MP syndrome (MPS) is the myofascial trigger point (MTrP), a very small, localized area of muscle contraction that is hard to the touch, and that is very tender. The trigger point is always located on a discrete band of hardness located within a muscle. The diagnosis of MPS is made by palpation of the MTrP.

Introduction

Myofascial pain (MP) is a widespread and universal cause of soft tissue pain. Physicians commonly overlook this condition because of lack of awareness and training but it is a relatively simple diagnosis. The central feature of MP syndrome (MPS) is the myofascial trigger point (MTrP), a very small, localized area of muscle contraction that is hard to the touch, and that is very tender. The trigger point is always located on a discrete band of hardness located within a muscle. The diagnosis of MPS is made by palpation of the MTrP.

Features of the MTrP

The MTrP is always located on a tight or taut band of muscle. An MTrP that causes pain is always tender to palpation. When stimulated mechanically by palpation or by needling, it contracts sharply, referred to as local twitch response (LTR). The taut band limits stretch of a muscle and produces weakness that is rapidly reversed as the trigger point is inactivated. It can activate autonomic activity, such as vasodilation or constriction, goose bumps, or piloerection ( Box 1 ).

- 1.

Taut band within the muscle

- 2.

Exquisite tenderness at a point on the taut band

- 3.

Reproduction of the patient’s pain

- 4.

Local twitch response

- 5.

Referred pain

- 6.

Weakness

- 7.

Restricted range of motion

- 8.

Autonomic signs (skin warmth or erythema, tearing, piloerection [goose-bumps])

The MTrP, like other physical sources of chronic pain, refers pain to distant sites and leads to central nervous system sensitization. Central sensitization results in a lower pain threshold and in tenderness, and in an expansion of painful areas, including an increase in MTrPs. MTrPs can be spontaneously painful (so-called “active” MTrPs) or they can be nascent or quiescent (so-called “latent” MTrPs), inactive until physical activity converts them to active MTrPs.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of MPS is based on a pertinent history and physical examination. Objective means of identifying the MTrP exist, but are generally not used in clinical practice because they are costly, time-consuming, and are not available to most practitioners. Now that high-definition ultrasound (HDUS) is more widely available, there is interest in using it to guide the practitioner in performing injection or deep dry needling of difficult muscles using HDUS guidance. The experienced hand is faster and quite adequate at identifying the site to be needled.

History

MP can be acute pain or chronic muscle pain. The nature of the pain in both cases is dull, deep, aching, and poorly localized. It is rarely sharp and stabbing, although acute episodes of stabbing pain can occur, even on a background of chronic pain. It mimics radicular or visceral pain. Somatic pain from trigger points in the abdomen, for example, can feel like irritable bowel, bladder pain, or endometrial pain. Trigger points in the gluteus minimus muscle refer pain down the side and back of the leg, like L5 or S1 radicular pain. It can be accompanied by a sensory component of paresthesias or dyesthesias but does not present in this manner. Paresthesias, such as tingling, when present, are generally distributed in the dermatome of the nerve root(s) innervating the muscle harboring the relevant trigger point. Pain is often experienced as referred to other regions, such as the head, the neck, or the hip, as referred pain (RP). MP can also be the presenting symptom for radiculopathy, or major joint pain (shoulder or hip). MPS persists long after the initiating cause of pain has resolved. Hence, the story of a remote injury can be relevant.

Thus, the onset of the pain, the regions involved, the timing and pace of progression, and the quality of the pain, are important elements of the history. In addition, there are certain predisposing factors that make MP more likely to occur. These include iron deficiency (most commonly caused by menstrual blood loss in women, but also from dietary insufficiency), hypothyroidism, and deficiency of vitamin D or B12. Lyme disease, hypermobility, and spondylosis also predispose to the development of MP. Parasitic infections can manifest as widespread trigger point pain. Questions about travel and backpacking are therefore relevant as well.

Physical Examination

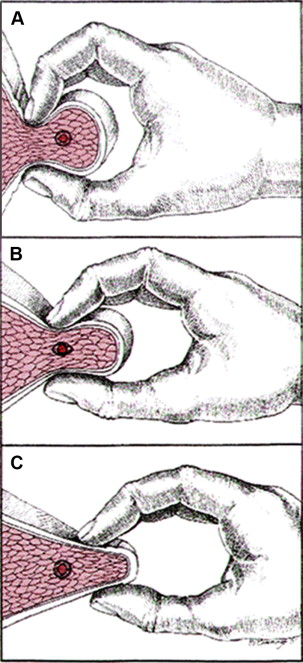

The diagnosis of MPS is made by the identification of an MTrP and relating it to the patient’s pain complaint ( Box 2 ). A MTrP is identified by palpation. The MTrP is characterized by the presence of a taut band palpable within muscle. The taut band can be palpated in almost every muscle, with some initial guidance and practice. It is also tender when it is the immediate cause of the patient’s pain. Thus, MTrP-containing muscle has a heterogeneous feel of hard and soft areas, rather than a homogeneous uniform consistency. The intense contraction of the trigger point results in a sensory phenomenon of localized, exquisite pain that is always associated with the taut band. Moreover, some taut bands are not painful to palpation, but have functional consequences, such as altering the normal sequence of muscle activation. The taut band must be palpated cross-fiber, that is, perpendicular to the direction of the muscle fiber. The direction of muscle fiber may not be obvious, especially in pectoral muscles, the infraspinatus muscle, and the gluteal muscles.

- 1.

History and pain diagram: the history identifies the areas affected by pain

- 2.

Examination of muscles whose trigger points can refer pain to the affected areas

- 3.

Palpate the muscle for taut bands, using either flat palpation or pincer palpation

- 4.

Move the fingers along the taut band to find the hardest and most tender spot (the trigger point)

- 5.

Compress the trigger point manually and ask (1) if the spot is tender or painful, and if so, (2) does the pain resemble the patient’s usual pain

- 6.

Compress the trigger point for 5–10 seconds and then ask if there is pain or some sensation away from the trigger point (referred pain)

Palpating the Taut Band

An MTrP is always palpated perpendicular to the direction of the muscle fiber so as to detect the taut band. Palpation overlying a firm or bony structure is palpated by compressing the muscle against it ( Fig. 1 ). When the muscle can be grasped between the fingers, the muscle is palpated by a pincer grip with the thumb and the index and long fingers ( Fig. 2 ). When a taut band is identified, the examining fingers move along the band to identify the small region of greatest hardness, the area of least compliance to compression. It is this area that is most tender. This is the center or heart of the trigger point. Stimulation of this area induces RP. It is in this area that mechanical stimulation elicits the LTR. The farther away stimulation is from this center, the more difficult it is to elicit RP and the LTR, until they cannot be elicited at all. The LTR cannot be elicited at all when the taut band is stimulated 3 cm or more from the trigger point zone. The importance of locating the area of greatest hardness in the taut band, which is the area of greatest tenderness, is that this is the area that is to be treated. Compression of the trigger zone for 5 to 10 seconds can induce referred pain, or pain that is at a distance from the point of stimulation because RP represents central activation or central sensitization. It requires activation of interneurons and spreads rostrally and caudally in the spinal cord, which does not occur instantaneously. Hence, 5 to 10 seconds of compression is needed to be certain that the palpated MTrP induces RP. Once the MTrP is identified, determined to be tender, and RP is confirmed, the patient is asked if the pain or tenderness, local or referred, reproduces or is like all or part of his or her usual pain. That relates a particular MTrP to a patient’s complaint. Identifying an MTrP that is related to the presenting or another complaint aids in determining which trigger points need to be treated and in what order.

A tender trigger point is an indication that there is hyperalgesia or allodynia. Pain at the MTrP is due to the release of neuropeptides, cytokines, and inflammatory substances, such as substance P, calcitonin gene–related peptide, interleukin-1α, and bradykinin, and protons that create local acidity. Models for acute muscle pain have been developed and have yielded information about the generation of local and referred pain. However, most clinically relevant muscular pain syndromes last far longer than the conditions studied in animals or humans under laboratory conditions. Therefore, there is great interest in studying longer-lasting and chronic pain in humans.

Taut Bands

A taut band does not need to be tender because MTrPs are dynamic, being quiescent (when they do not cause pain) or resolve with rest, massage, or stretch. They are activated with movement or action, including psychological stress. When they are quiescent, the MTrP does not reproduce pain (ie, spontaneously cause pain), but that was nonetheless tender to palpation. A taut band that is not tender to palpation will not, of course, reproduce pain unless it does so by causing RP. Such taut bands restrict movement because taut bands are not innocuous with deleterious functional effects. Lucas and colleagues have shown a latent MTrP disrupts the normal sequence of muscle activation. They can activate central effects, such as decreasing the threshold for pain activation distally. They limit muscle lengthening and have a role in activating other MTrPs. Hence, determination of treatment is to be made to treating taut bands, whether latent or not. The decision requires a judgment about whether a taut band is clinically relevant or not. This is not always clear and, therefore, the taut band may be treated more often than not.

Additional Trigger Point Characteristics

LTR is elicited by mechanical stimulation of the taut band causing local contraction. This is differentiated from a Golgi tendon reflex, which involves contraction of an entire muscle in response to stretch. The LTR is a brief (25–250 ms), high-amplitude, polyphasic electrical discharge. The discharge is attenuated when the stimulation is remote from the trigger zone. The twitch response is dependent on an intact spinal cord reflex arc. Severing the peripheral nerve completely abolishes the local twitch response, whereas transecting the spinal cord does not abolish the twitch response. Thus, the local twitch response is mediated through the spinal cord, and is not affected by supraspinal influences. The twitch response is unique to the MTrP and is not seen in healthy muscle.

Referred Pain

RP represents spread through a central nervous system that has been activated (ie, spread that is facilitated by central sensitization). It is most common in the distribution of the nerve innervating the muscle with the trigger point being activated. Thus, a trigger point arising in the infraspinatus muscle, primarily innervated by the C5 nerve root, tends to refer pain to other C5-innervated muscles, with a spillover to C4 and C6 innervated muscles. The primary referral patterns reflect the arborization and spread of incoming first-order neuronal axons within the spinal cord. The nociceptive spread or arborization of incoming axons is far greater than that of touch and position sense. Hence, there is the potential for greater spread of pain than for perception of touch. Moreover, as incoming nociceptive impulses become more intense and the duration of central nociceptive neurons becomes longer, central sensitization results in a greater extent of increased synaptic efficacy through more distant spinal segments, a result of the neuroplastic changes that accompany central sensitization and RP encompasses ever far-reaching parts of the body. RP can be felt over many spinal cord segments, and in extreme cases can appear to be bizarre and body wide. MTrP points in the ventral (anterior) trunk muscles can even refer to the dorsal (posterior or back) muscles.

Limited Range of Motion

Limited range of motion (ROM) is due to pain on lengthening a muscle harboring an MTrP and to the limitations imposed by the shortened taut band. ROM testing can be misleading because of the potential multiple pathologies that can limit motion about a joint, and, additionally, normal ROM is variable depending on the individual, such as hypermobile individuals.

Examination of ROM can be a useful clue in determining which muscles harbor trigger points. Limited rotation of the head and neck to the left can implicate the left sternocleidomastoid and/or trapezius muscles, or the right splenius cervicis and oblique capitis inferior muscles, all muscles that have to lengthen to accomplish this movement. An additional limitation of head and neck side bending right would focus attention on the left sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

Weakness

Weakness is often but not always evident in a muscle harboring a trigger point. Weakness in affected muscles is rapidly reversed as the trigger point is inactivated. Hence, weakness does not represent a neuropathic or myopathic process, but appears to be a form of muscle inhibition that may be central. This phenomenon has not been well studied.

Autonomic changes

Vascular dilation and constriction occur as a result of autonomic nervous system activation, resulting in erythema or blanching, and warm or cool areas usually in the distribution of the nerve innervating an affected muscle.

Diagnostic Criteria

There is some debate in the literature as to what is needed to diagnose an MTrP (and hence, diagnose MPS). Articles often state that the diagnosis of MP is made using the criteria of Simons and colleagues. Simons and colleagues described at least 7 features of the trigger point: (1) taut band, (2) exquisite tenderness on the taut band, (3) reproduction of pain, (4) local twitch response, (5) restricted ROM, (6) autonomic symptoms, and (7) RP. To this is often added a nodular hardness at the trigger point. Not all features described are present at any one time, and not all are necessary to identify a trigger point and make a diagnosis. This question has not been answered definitively at this time, but the presence of a taut band that is tender and that reproduces the patient’s pain complaint in full or in part is sufficient to base a treatment program. These criteria, a tender, taut band that reproduces the patient’s pain, allow the clinician to select a trigger point for treatment. The proof of efficacy is that treatment based on these criteria alone is sufficient to reduce or eliminate pain, which is our experience, although there has not been a study confirming this.

One can ask if identification of a taut band is enough to make a diagnosis. However, to diagnose a pain syndrome, one must have pain, so that it makes sense that tenderness or pain must be elicited by examination so as to diagnosis MPS. However, a nontender taut band should be treated in a patient with trigger point pain syndrome when it is likely to have significant clinical effects, like restricting motion or producing weakness.

There are a number of studies that have shown inter-rater reliability of the physical examination of an MTrP, starting with the study by Gerwin and colleagues. Subsequent studies were more sophisticated and showed that clinicians could agree on the identification of the same trigger point, not just the muscle(s) that harbored MTrPs. Sciotti and colleagues showed that examiners could independently identify the same taut band region. Interrater reliability of MTrP palpation in shoulder muscles was demonstrated by Bron and colleagues.

A number of reviews have been published questioning the data and purporting to show that physical examination is not reliable, but these reviews show a fundamental lack of understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the MTrP, which biases the author’s conclusions. For example, one such review discounted a number of positive studies because the investigators did not specify that they looked for a “nodule” in the taut band, a feature they said was mentioned as essential by MP “experts.” In fact, “all” the experts they were referring to turned out to be Dr David Simons. Simons was referring to the area of tender hardness on the taut band. One has to identify the taut band and to elicit tenderness, but there is no need to identify the region as nodular rather than linear to make a diagnosis. Simons never made a point that identifying a nodularity in the taut band was necessary for identifying a trigger point. The MTrP may simply be described as a sense of swelling, but often all that the palpating finger feels is hardness on the taut band.

Diagnostic Inactivation of the Trigger Point

An active MTrP is symptomatic and can be assessed for a particular complaint of pain, like headache pain or shoulder or low-back pain. Reproduction of the patient’s pain complaint is important in determining if a particular trigger point is clinically significant. When there is doubt about the clinical significance of a particular trigger point, it can be inactivated either manually, by using a laser, by deep dry needling, or by a trigger point injection. An immediate (with 2–3 minutes) unequivocal decrease in pain is good evidence that the MTrP in question is clinically relevant. Sometimes the relief of pain can be dramatic, as in piriformis syndrome, and readily leads to an effective treatment plan ( Box 3 ).