Dermatologic Disorders

General Examination

Examination of the skin is an extremely important part of the evaluation of the upper extremity. The clinician should note the overall appearance, texture, and color, as well as the presence of any skin lesions, rash, nicotine stains, and nail abnormalities. The way the hand has been used can be determined by the presence or absence of calluses on the palm and fingers.

Differential Diagnosis

The appearance of the skin can give the physician clues as to the underlying disease process. For example, in reflex sympathetic dystrophy the skin may have abnormal sweating, appear shiny, and lose its normal wrinkled appearance. After a nerve transection, the skin becomes dry and there is a demonstrable loss of sweat in the sensory dermatomal distribution of the injured nerve.

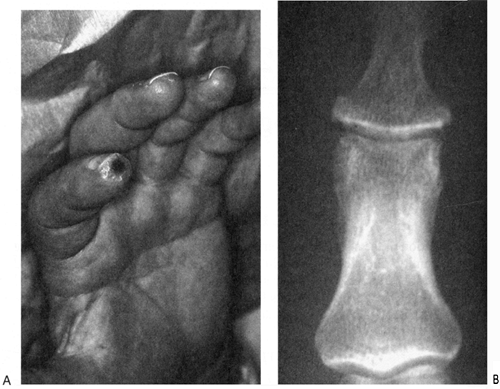

Skin ulcers can be seen at the tips of the digits in conditions associated with ischemia (i.e., scleroderma, Buerger’s disease, Raynaud’s disease, and Crest syndrome) (Fig. 1).

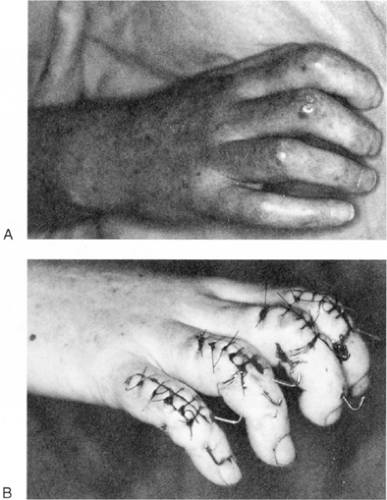

Scleroderma is associated with fingers that become slender, shiny, and immobile (metaphalangeal [MP] extension contractures and proximal interphalangeal [PIP] flexion contractures). Skin breakdown and ulcers are common in areas where the skin is stretched, such as over the dorsum of the proximal interphalangeal joints with PIP flexion contractures (Fig. 2).

It is important to note any evidence of psoriasis, which may include a scaly, erythematous skin rash over extensor surfaces of the elbow and several other areas of the body. Typical nail findings in psoriasis include pitting and crumbling. Approximately 5% of patients with psoriasis have an inflammatory arthritis, and 15% to 20% of patients develop the skin lesions after the onset of arthritis. Isolated proximal interphalangeal joint swelling is commonly seen with psoriatic arthritis. Psoriatic arthritis, unlike rheumatoid arthritis, can be asymmetric (Fig. 3). Osteolysis at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints results in a “pencil in cup” appearance.

Onychomycosis

Fungal infections of the nail, most commonly seen in the toes, can also be seen in the fingers (Fig. 4). Predisposing factors include heat, moisture, trauma, false nails, diabetes, inheritance, aging, and altered immunologic status. The diagnosis can be confirmed by a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation from the nail clippings or subungual keratotic debris.

Treatment

A combined surgical and medical approach may be indicated. The diseased nail can be cut back or completely removed and the underlying nail bed curetted in an attempt to debulk the fungus. Several topical preparations have been used with limited, temporary success. Lamisil cream (terbinafine hydrochloride 1%) has been the most effective and should be applied for 2 to 3 months. Oral griseofulvin was used in the past. Pulsed treatment of oral Sporanox (itraconazole) is recommended: 200 mg bid for 1 week separated by

a 3-week period, followed by 1 more week of treatment. (Pulsed treatment is not recommended when treating the toes.)

a 3-week period, followed by 1 more week of treatment. (Pulsed treatment is not recommended when treating the toes.)

FIG. 2. A: A woman with scleroderma with metaphalangeal extension contractures and PIP flexion contractures. Note skin breakdown over dorsum of proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints. B: Treatment with multiple PIP fusions in a more extended position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|