Postmastectomy pain syndrome is a common sequela of breast cancer treatment that can lead to impairments and limited participation in work, recreational, and family roles. Pain can originate from multiple anatomic sites. A detailed evaluation to determine the specific cause or causes of pain will help guide the clinician to successfully manage this pain syndrome. There are many available treatments, but more evidence is needed for the efficacy of rehabilitation, pharmacologic, and nonpharmacologic therapy. There is evidence for some effective treatments to prevent this syndrome, but, here also, more research is needed.

Key points

- •

Postmastectomy pain syndrome is a prevalent disorder that negatively impacts the function and quality of life of breast cancer survivors.

- •

The key to successful treatment of postmastectomy pain is a thorough evaluation to identify the specific anatomic structures that lead to this pain syndrome.

- •

After determining the anatomic cause of postmastectomy pain, there are many potential treatments, including rehabilitation, medications, injections, and other nonpharmacologic treatments.

Background

Epidemiology of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in the United States, irrespective of race or ethnicity, accounting for nearly 1 in 3 cancers. Each year, there are more than 230,000 new cases of breast cancer in the United States and more than 40,000 deaths. It is the second leading cause of cancer death among women after lung cancer and the most common cause of death from cancer among Hispanic women according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in 8 women will develop invasive breast cancer. Approximately one million new cases are diagnosed globally every year, and this number is expected to increase in future decades. As a result, more women will likely undergo surgical procedures for the treatment of breast cancer, and the incidence of postoperative complications and pain syndromes is likely to increase.

Surgical Techniques in the Treatment of Breast Cancer

In the past several decades, the standard of care for the treatment of breast cancer involved radical mastectomy and total axillary dissection to achieve local tumor control and increase the likelihood of cure. Over the years, less invasive surgical approaches have become the standard of care and include modified radical mastectomy, total (simple) mastectomy, and more recently, skin-sparing mastectomy and nipple-sparing mastectomy. These less invasive surgical techniques have continued to gain favor over time. These more conservative surgical approaches have enhanced rates of local control and 5-year survival, in part due to a gradual shift from unimodal to multimodal treatment approaches.

Treatment options for patients with early stage breast cancer typically include total mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery with adjuvant radiation therapy. Total mastectomy involves removal of skin, nipple, areola, breast tissue, and the fascia of the pectoralis major. Patients who have undergone total mastectomy may be candidates for immediate breast reconstruction, which is increasingly used with a skin-sparing mastectomy technique, especially for women with smaller breasts. Regardless of specific technique, all patients with invasive breast cancer should undergo sampling of axillary lymph nodes for proper staging and treatment.

Until the late 1990s, it was standard of practice for patients to undergo 2- to 3-level axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in addition to breast-conserving treatment or mastectomy. The extent of lymph node dissection can potentially be limited by the identification of the axillary sentinel lymph node(s) (SLN) using a radiolabeled isotope. Based on predictable patterns of lymphatic drainage within the breast, SLN identification limits nodal dissection and may allow for immediate completion ALND in cases with metastatic disease within the sentinel node.

Finally, women who undergo mastectomy for the treatment or prevention of breast cancer often consider cosmetic reconstruction. Multiple surgical techniques are currently used and include single-stage reconstruction, tissue expansion followed by implant, combined autologous tissue/implant reconstruction, and autologous tissue reconstruction alone. Common approaches to autologous breast reconstruction include transverse rectus abdominus muscle flap, latissimus flap, and deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Reconstruction is deemed safe from an oncology perspective and can improve appearance, sense of femininity, and self-esteem.

Background

Epidemiology of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women in the United States, irrespective of race or ethnicity, accounting for nearly 1 in 3 cancers. Each year, there are more than 230,000 new cases of breast cancer in the United States and more than 40,000 deaths. It is the second leading cause of cancer death among women after lung cancer and the most common cause of death from cancer among Hispanic women according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One in 8 women will develop invasive breast cancer. Approximately one million new cases are diagnosed globally every year, and this number is expected to increase in future decades. As a result, more women will likely undergo surgical procedures for the treatment of breast cancer, and the incidence of postoperative complications and pain syndromes is likely to increase.

Surgical Techniques in the Treatment of Breast Cancer

In the past several decades, the standard of care for the treatment of breast cancer involved radical mastectomy and total axillary dissection to achieve local tumor control and increase the likelihood of cure. Over the years, less invasive surgical approaches have become the standard of care and include modified radical mastectomy, total (simple) mastectomy, and more recently, skin-sparing mastectomy and nipple-sparing mastectomy. These less invasive surgical techniques have continued to gain favor over time. These more conservative surgical approaches have enhanced rates of local control and 5-year survival, in part due to a gradual shift from unimodal to multimodal treatment approaches.

Treatment options for patients with early stage breast cancer typically include total mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery with adjuvant radiation therapy. Total mastectomy involves removal of skin, nipple, areola, breast tissue, and the fascia of the pectoralis major. Patients who have undergone total mastectomy may be candidates for immediate breast reconstruction, which is increasingly used with a skin-sparing mastectomy technique, especially for women with smaller breasts. Regardless of specific technique, all patients with invasive breast cancer should undergo sampling of axillary lymph nodes for proper staging and treatment.

Until the late 1990s, it was standard of practice for patients to undergo 2- to 3-level axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in addition to breast-conserving treatment or mastectomy. The extent of lymph node dissection can potentially be limited by the identification of the axillary sentinel lymph node(s) (SLN) using a radiolabeled isotope. Based on predictable patterns of lymphatic drainage within the breast, SLN identification limits nodal dissection and may allow for immediate completion ALND in cases with metastatic disease within the sentinel node.

Finally, women who undergo mastectomy for the treatment or prevention of breast cancer often consider cosmetic reconstruction. Multiple surgical techniques are currently used and include single-stage reconstruction, tissue expansion followed by implant, combined autologous tissue/implant reconstruction, and autologous tissue reconstruction alone. Common approaches to autologous breast reconstruction include transverse rectus abdominus muscle flap, latissimus flap, and deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. Reconstruction is deemed safe from an oncology perspective and can improve appearance, sense of femininity, and self-esteem.

Postmastectomy pain syndrome

Definition

Postmastectomy pain syndrome (PMPS) refers to persistent pain following any breast surgery, not just mastectomy. Pain has been reported following other breast procedures, including lumpectomy, breast reconstruction, augmentation, and reduction, although procedures targeting the upper outer quadrant of the breast or axilla are particularly prone to pain syndromes. For a diagnosis of PMPS, pain must persist for more than 3 months postoperatively when all other causes of pain, such as infection or tumor recurrence, have been excluded ; however, no specific diagnostic criteria are universally accepted. Persistent pain after mastectomy was first reported during the 1970s and was characterized as a dull, burning, and/or aching sensation in the anterior chest, arm, and axilla, often worsened by movement of the shoulder. There are various potential causes of PMPS, including intraoperative damage to the intercostobrachial nerve, axillary nerve, or chest wall; phantom breast pain; incisional pain; musculoskeletal pain; and pain caused by neuroma. Although traditionally, PMPS has been defined in the literature as a neuropathic pain syndrome, the authors of this article believe this to be an inaccurate generalization. Many patients with PMPS have musculoskeletal pain syndromes with no apparent component of neuropathic pain.

Epidemiology

Reported incidence rates of PMPS have varied significantly, perhaps as a result of the absence of a formalized definition or diagnostic criteria. Most studies of chronic pain following breast surgery report an incidence ranging from 20% to 70%. One study showed 44% of breast cancer survivors still with arm pain more than 4 years after breast surgery. It is likely that incidence rates differ across anatomic subsets of postmastectomy pain. Therefore, more accurate and clinically relevant incidence estimates may require broad acceptance and application of subset-specific diagnoses.

An important characteristic that distinguishes PMPS subtypes and has direct import for clinical decision making is the presumed pathophysiology of the pain. Nociceptive pain occurs as a result of surgical injury and typically resolves as damaged tissue heals. Musculoskeletal pain syndromes are common nociceptive causes of PMPS, but for most, epidemiology remains uncharacterized. In contrast, neuropathic pain results from dysfunction of the nervous system and may be difficult to treat. Several different types of neuropathic pain following breast surgery have been described. Phantom breast pain may occur after radical mastectomy or modified radical mastectomy and refers to the sensation of a removed breast or nipple that is painful. Studies have estimated the prevalence of phantom breast pain from 13% to 44%. Intercostobrachial neuralgia refers to pain related to surgical injury to the intercostobrachial nerve, which may occur following axillary dissection and is a commonly discussed cause of PMPS in the literature, although rigorous incidence estimates are lacking. Neuromas are another cause of chronic pain after breast surgery and may form following injury to any nerve. Neuromas can form within scars following both mastectomy and lumpectomy, although pain from neuroma may be more common following lumpectomy or in patients who have undergone concomitant ALND and radiation. The prevalence of neuroma pain following breast surgery varies throughout the literature and ranges from 20% to 50%. Additional causes of neuropathic pain are also possible and include damage to the intercostal, thoracodorsal, medial and lateral pectoral nerves, and long thoracic nerves.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with PMPS typically present with neuropathic or musculoskeletal pain symptoms. Symptom onset may be in the immediate postoperative period, but can also occur several months after surgery and persist beyond the normal timeframe for surgical healing. Pain is commonly localized to the axilla, operative site, and/or ipsilateral arm. Patients may also experience pain in the chest wall and/or shoulder with accompanying limitations in range of motion, or decreased handgrip strength.

Risk Factors

Reasons for the development of persistent pain following a mastectomy are not clearly understood and are likely multifactorial. Risk factors span clinical and demographic domains, including the severity of acute postoperative pain, adjuvant radiation, ALND, and psychosocial factors. Severe postoperative pain that becomes chronic has been studied after various surgical procedures. Persistent acute pain is thought to activate mechanisms within the central and peripheral nervous systems, leading to sensitization. This, in turn, leads to allodynia, hyperalgesia, and hyperpathia that can affect physical functioning and lead to chronic pain. In a study of 569 patients reported by Tasmuth and colleagues, patients with significant postoperative pain were more likely to develop persistent ipsilateral arm pain compared with those whose pain was less severe.

Demographic risk factors

Younger age at diagnosis is associated with increased risk for PMPS. Although the reason for this is poorly understood, several mechanisms have been proposed. These mechanisms include greater sensitivity to nerve damage in younger people, lower pain thresholds, and increased preoperative anxiety. In addition, younger age may be correlated with more aggressive treatments, including a more thorough axillary dissection and adjuvant radiotherapy.

Socioeconomic status has also been associated with PMPS. Patients with lower socioeconomic status, including lower annual income and educational level, are predisposed to develop higher rates of chronic pain. One explanation for this may be diagnosis at later stages of cancer, necessitating more aggressive surgical and adjuvant treatment.

Treatment- and complication-related risk factors

Although it is commonly assumed that PMPS is a sequela of mastectomy, large-scale studies show no difference in PMPS rates between mastectomy and lumpectomy. Rather, it is the extensiveness of ALND, damage to the intercostobrachial nerve, and adjuvant treatment that are presumed to initiate and sustain postoperative and chronic pain. Tumors located in the upper outer quadrant may warrant a more extensive axillary dissection, leading to greater neuropathic pain. Furthermore, the number of axillary lymph nodes dissected as well as the number and location of surgical drains may play a role. Immediate reconstruction following mastectomy has not been found to effect the development of PMPS.

Adjuvant radiation therapy to the axilla is another potential cause of neuropathic pain in patients with breast cancer. Pain related to radiation can occur months to years following treatment, even in those patients who undergo breast conservation surgery. Pain following radiation can present in the breast, chest wall, and ipsilateral arm.

One study demonstrated that surgical complications, such as cellulitis, and the development of neuromas and seromas, do not increase the risk of developing chronic pain.

Psychosocial risk factors

In terms of psychosocial risk factors for the development of PMPS, patients with moderate postoperative pain reported significantly higher preoperative levels of depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and fatigue as well as lower social well-being and quality of life. Almost half of all patients with cancer exhibit some elements of anxiety and depression. In one study of women with breast cancer, 50% were noted to have depression and anxiety within the first year of diagnosis. In a study of 611 patients undergoing a mastectomy, preoperative catastrophizing was the only independent contributing factor to predicting clinically significant pain at 2 days after breast surgery. Catastrophizing and maladaptive coping behavior may mediate postoperative pain by way of central and peripheral sensitization and impaired pain inhibition ( Box 1 ).

- •

Severity of acute postmastectomy pain

- •

Radiation

- •

ALND

- •

Younger age

- •

Low socioeconomic status

- •

Preoperative and postoperative anxiety and depression, especially catastrophizing

Clinical assessment of postmastectomy pain syndrome

History

Evaluation of PMPS requires a careful history and physical examination, which should focus on identifying the cause of the pain and the pain generator(s). History should include the timing of symptom onset, the type of breast surgery (mastectomy vs lumpectomy), type of reconstruction, and whether the patient had an ALND or SLN biopsy. The clinician should be aware of how many lymph nodes were removed and how many were positive for metastatic disease. In addition, the patient’s tumor stage and grade should be noted. Adjuvant treatment should be included in the history, including type and duration of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy.

A careful history of the patient’s pain should be taken. The distribution, duration, and quality of the pain, as well as associated symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and weakness, should be included. Phantom pain/sensations, breast pain, and/or swelling should be assessed. It is important to determine whether the patient has difficulty with shoulder motion or a history of premorbid shoulder dysfunction. Finally, the patient’s psychosocial status should be evaluated, including mood, coping skills, and extent of social support. Underlying depression and anxiety should be noted and addressed. Functional history, including activities of daily living, as well as vocational and avocational activities, before and after cancer diagnosis should be assessed ( Box 2 ).

- •

Surgical factors (timing, lumpectomy vs mastectomy, ALND vs SLN biopsy, type of reconstruction)

- •

Cancer pathology, stage, grade, estrogen/progesterone receptor status, metastatic disease

- •

Adjuvant treatments (chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy)

- •

Pain history

- •

Functional history

- •

Social status and support system

- •

Assess for anxiety and depression

Physical Examination

Physical examination includes examination of the breasts, skin, and upper extremities for any signs of cellulitis, radiation-association change, muscle atrophy, scapular winging, or lymphedema. The surgical incision should be evaluated for signs of wound infection, adhesions, seromas, and neuromas. The cervical and thoracic spine should be inspected for deformities and range-of-motion testing should be performed. The trapezius, serratus anterior, pectoralis muscles, rhomboids, and latissimus muscles should be palpated for potential asymmetry, trigger points, or other stigmata of myofascial dysfunction. For patients who have undergone breast reconstruction, special attention should be given to the pectoralis and lateral chest wall muscles, as well as the flap harvest sites, such as the abdomen. The axilla should be palpated for cording or masses. Shoulder girdle examination should include inspection for asymmetry, passive and active range of motion, as well as palpation and provocative testing of the rotator cuff and other musculoskeletal structures. In addition to testing strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes of the upper extremity myotomes and dermatomes, the neurologic examination should focus on motor testing of the muscles innervated by nerves that can be affected by surgery of the breast. These include the thoracodorsal, long thoracic, medial, and lateral pectoral nerves ( Box 3 ).

- •

Inspecting skin, incision, breast, cervical spine, shoulder girdle (for atrophy, asymmetry, or scapular winging)

- •

Palpate incision for tenderness, neuromas, and mobility

- •

Palpate musculature for tender/trigger points

- •

Palpate axilla and upper extremity for cording

- •

Range of motion

- •

Neurologic examination

- •

Special provocative tests depending on suspected diagnosis (eg, rotator cuff impingement signs)

Diagnostic Studies

Diagnostic studies can support and supplement the history and physical examination and aid the clinician when the diagnosis is unclear. Ultrasound can be helpful in diagnosing musculoskeletal abnormality. MRI may confirm shoulder, cervical spine, or thoracic spine abnormality. A chest computed tomographic scan or MRI can evaluate potential metastatic disease or brachial plexus injury. PET scanning can also be ordered if tumor recurrence or metastatic disease is suspected. Nerve conduction studies and electromyography can diagnose radiculopathy, plexopathy, mononeuropathies, polyneuropathy, or evidence of radiation fibrosis, for example, myokymia and/or myopathic motor unit action potentials.

Outcome Measures

Although standardized outcome measures in the setting of postmastectomy pain have not been clearly delineated, there are several well-established breast cancer–specific functional outcome measures. A prospective surveillance approach with functional measures for breast cancer has been proposed. The authors suggested serial functional evaluations with a 6-minute walk test, chair stand, shoulder range of motion, hand grip strength, upper extremity functional index or Kwan’s arm problem scale, and functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast or Breast-Q.

Postmastectomy pain syndrome diagnostic subgroups

The key to successful treatment of PMPS is to determine the specific pain cause or causes. The following section details pain generators that can lead to PMPS and suggested treatment approaches. Some treatments are evidence based, and some reflect anecdotal experience.

Rotator Cuff Dysfunction

Rotator cuff dysfunction, the leading cause of shoulder pain in the general population, is also a well-recognized phenomenon among breast cancer survivors. The frequency of rotator cuff–related pain among breast cancer survivors has not been rigorously estimated. Altered biomechanics have been implicated in the development of rotator cuff dysfunction, whether after mastectomy or lumpectomy. Postmastectomy scapulothoracic motion has been noted to increase disproportionately to glenohumeral motion, with subsequent rotator cuff microtrauma and tendinopathy. This is due to postoperative glenohumeral range-of-motion limitations and decreased muscle activity in the musculature affecting the scapula (serratus anterior, upper trapezius, pectoralis major, and rhomboid) ipsilateral to the carcinoma. The shoulder girdle is placed in a more protracted and inferior position as a result of shortening of the pectoral muscles and associated soft tissues, thus narrowing the subacromial space available for the rotator cuff tendons. Symptoms include pain, tightness, decreased function, and weakness. Kyphotic posture can also contribute to pectoralis muscle tightness, resulting in further rotator cuff impingement. It should be noted that studies have shown altered scapulothoracic motion contralateral to the cancer, explaining the occurrence of bilateral shoulder dysfunction, or even unilateral involvement of the unaffected side.

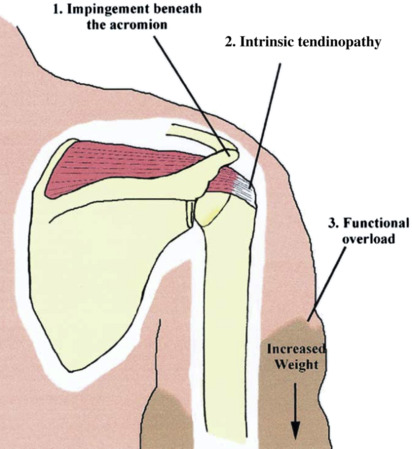

Other risk factors may contribute to rotator cuff dysfunction in patients with breast cancer. Chest wall radiation treatment contributes to muscle and soft tissue tightening; fibrosis may be a major factor in this phenomenon. Interestingly, one study demonstrated that chest wall radiation involving the pectoralis major, regardless of the presence of clinically detectable radiation fibrosis, was a significant contributor to shoulder morbidity. A review of several studies involving radiotherapy demonstrated that the addition of axillary radiation places patients at increased risk for late shoulder dysfunction compared with chest wall radiation alone. Lymphedema also contributes to rotator cuff tendinopathy. The incidence of shoulder pain in lymphedema patients is reported as 53% and 71% from 2 separate studies. Increased weight of the limb and decreased joint range of motion can aggravate subacromial impingement, intrinsic tendinopathy, and/or functional overload ( Fig. 1 ). In addition, reports have speculated that the increased risk of cellulitis in the lymphedematous arm may decrease healing capacity of tissue and cause pathologic effects on the rotator cuff, but this has not been validated. Early management of lymphedema has been suggested given the association noted between the duration of lymphedema symptoms and, rotator cuff abnormality seen on musculoskeletal ultrasound.