Congenital Radial Head Dislocation

CASE PRESENTATION

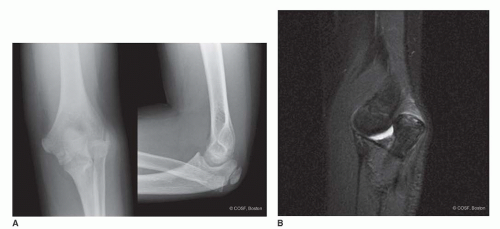

A 13-year-old male presents with an isolated unilateral congenital dislocation of the radial head on the left side. He is right-hand dominant. Diagnosis was made at age 8 when he and his family noted a prominence on the lateral aspect of his elbow, and he began experiencing pain. Then he lacked only 5 degrees of elbow extension with pronation to 70 degrees and supination to 30 degrees and minimal pain with sports. Over the past 5 years, he developed increasing pain, mild loss of motion, and, most recently, in the past 3 months, intermittent locking of his elbow. He is now limited in both athletics and activities of daily living. On exam, his radial head is prominent posterolaterally. He has flexion to 130 degrees and extension to -40 degrees. His forearm rotation is 60 degrees pronation and 5 degrees supination. His radiographs and MRI scan are outlined in Figure 16-1.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

How do you distinguish a congenital from a traumatic radial head dislocation?

Is there a predominant direction of dislocation for a congenital radial head?

What are the associated upper limb conditions and systemic syndromes with a congenital radial head dislocation?

Are there functional limitations with a congenital dislocation of the radial head?

What are the indications for open reduction of a congenital radial head dislocation?

Is it appropriate to excise a dislocated radial head in a skeletally immature child?

What are the expected outcomes from operative intervention?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Congenital dislocation of the radial head needs to be distinguished from a traumatic dislocation. It has been written that a unilateral dislocation indicates traumatic etiology.1 That is not true, though bilateral dislocations are clearly more commonly congenital.2,3 It has been stated that direction of displacement distinguished congenital from traumatic dislocations. That also is not true, though anterior dislocations tend to be more traumatic and posterolateral dislocations more congenital in origin (Figure 16-2). The local changes in the capitellum, radial head, and forearm alignment are very helpful in this distinction. In general, congenital dislocations will exhibit a convex, aspherical radial head; a hypoplastic, flattened capitellum; an elongated, bowed radial neck; an ulna greater than radial length; and mild proximal ulnar bowing. However, local and regional deformity does occur with traumatic dislocations. And just to add to the confusion, a congenital dislocation can suffer a fracture, and a traumatic dislocation has been described at birth.4,5

The reason all this matters is decision making regarding operative intervention.6 It is not unusual to be referred a patient from the emergency room for surgical intervention who has undergone multiple failed attempts at closed reduction of a misdiagnosed traumatic Monteggia lesion when he or she actually has an undiagnosed congenital dislocation of the radial head. Reconstruction of a chronic Monteggia may be successfully performed by a surgeon at the double black diamond level (see Chapter 30), if the radial head is not convex. Late reconstruction of a congenital dislocation will be fraught with failure except in very unusual circumstances.7,8

Etiology and Epidemiology

Congenital dislocation of the radial head can be seen in isolation, in conjunction with other congenital differences about the elbow and upper limb, or as part of a syndromic condition. Approximately 66% occur in isolation, while

33% are associated with regional or syndromic anomalies. The exact incidence in the general population of the isolated congenital dislocation is unknown. Congenital dislocations associated with ulnar dysplasia, radioulnar synostosis, below-elbow amputations, congenital pseudarthrosis of the ulna, osteogenesis imperfecta, nail patella syndrome, trisomy 8 and 12, omodysplasia, and familial inheritance, among others, are well described.9, 10, 11 and 12

33% are associated with regional or syndromic anomalies. The exact incidence in the general population of the isolated congenital dislocation is unknown. Congenital dislocations associated with ulnar dysplasia, radioulnar synostosis, below-elbow amputations, congenital pseudarthrosis of the ulna, osteogenesis imperfecta, nail patella syndrome, trisomy 8 and 12, omodysplasia, and familial inheritance, among others, are well described.9, 10, 11 and 12

Clinical Evaluation

The degree and direction of dislocation, along with associated conditions, affect the timing of presentation. Most isolated congenital dislocations do not present for evaluation and care until later in life, often around school age. The child’s lack of full elbow extension or forearm rotation may only be noted when specific arm and hand motion tasks are attempted under direct supervision or observation. The child’s compensatory shoulder and wrist motion usually prevents functional limitations and parental awareness until direct observation and inspection occurs. This is similar to the presentation of radioulnar synostosis (see Chapter 17).

FIGURE 16-2 Sagittal MRI scan of rare anterior congenital radial head dislocation with impingement against a hypoplastic capitellum. |

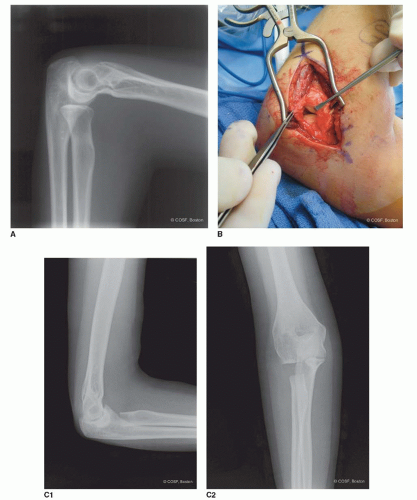

Early on, pain is rare, if present at all. Occasionally, the children will complain of instability with forearm rotation, or the parents will hear a snapping sound with rotatory motion in the subluxed or minimally dislocated situation13 (Figure 16-3). Later, osteochondral deterioration of the radial head and capitellum can create activity-related pain, produce loose bodies, and cause locking and crepitus. Some of these children present acutely to the emergency room with a locked joint or, more commonly, pain with activities such as sports.14

Finally, some adolescents only present when they are disturbed by the aesthetic appearance of a prominent posterolateral dislocation. Their desire for excision is more psychosocial than functional.

Examination of an isolated posterolateral dislocation usually reveals a 5- to 40-degree lack of elbow extension and <50% full forearm rotation. There is often compensatory wrist and shoulder rotation that prevents functional impairment. Bilateral involvement can be more disabling. With local dysplasia or syndromic conditions, the limitations on exam become more regional or systemic. If there is hand and/or brain involvement, the functional limitations become more marked.

FIGURE 16-3 (continued) D: Forearm x-ray revealing radial head resection and neutral ulnar variance. |

Radiographs will reveal the direction of dislocation. The contour of the radial head; bowing of the radial neck and shaft; radiocapitellar, proximal, and distal radioulnar articulations; distal ulnar variance; and shape and contour of the ulna are all evaluated on plain radiographs of the forearm, wrist, and elbow. Other regional anatomic abnormalities, such as radioulnar synostosis, are recorded. Osteochondral deterioration is noted. On rare occasions in which the diagnosis is made perinatally or in infancy, ultrasound or MRI scan is used to determine the feasibility of an open reduction.

Surgical Indications

One of the lessons of history is that nothing is often a good thing to do and always a clever thing to say. —Will Durant

The ideal surgical solution for a congenital dislocation of the radial head includes (1) early recognition by prenatal or infantile ultrasound and (2) successful operative reduction of the radial head that leads to proximal radioulnar and radiocapitellar joint remodeling, normal alignment, and motion. The first is often difficult, and there is debate if the second is achievable. Too often these children are not diagnosed until later in life due to minimally noticeable disability. It is not a common or severe enough problem to warrant neonatal screening, such as with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Usually at the time of diagnosis, there is too much radial head and capitellar deformity to warrant open reduction.7,15,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree