Complications of Surgery for Anterior Shoulder Instability

Thomas J. Gill

Bertram Zarins

The goals of surgery for shoulder instability are to restore stability while maintaining a pain-free, maximal range of motion. In the past, surgeons have performed operations that restored glenohumeral stability, but often at the price of decreased mobility or stiffness (1). Examples of these procedures are the Putti-Platt and Magnuson-Stack procedures. Recent outcome studies have reported that patients’ priorities are full mobility and function, even to the exclusion of absolute stability (2).

When complications do arise, the problems generally fall into one of several categories. These categories include recurrent instability, loss of motion without arthrosis, loss of motion with arthrosis, subscapularis ruptures, neurologic injuries, and hardware-related problems. In order to treat these complications successfully, there are several principles of treatment that are helpful to consider.

PRINCIPLES

Perhaps the most important principle of treatment when evaluating a complication of open instability surgery is to diagnose the exact reason for failure of the prior surgery (3). It is not enough to simply assume that a revision Bankart operation can be used to treat the recurrent instability. A precise anatomic explanation for the instability should be determined whenever possible.

It is helpful to start the patient interview by obtaining a history about the events that led up to the first instability procedure. What kind of symptoms was the patient having that led to the surgical intervention? Was it instability or pain only? If a trauma was involved, did the shoulder actually dislocate and require a formal reduction? In what position was the arm when the trauma occurred, and what position of the arm exacerbated the symptoms? These types of questions help to confirm that an accurate diagnosis of anterior instability was made prior to performing an anterior stabilization procedure.

If the patient had an initial Bankart procedure, but upon questioning had symptoms more consistent with posterior instability, then the reason for the patient’s instability complaints may not be due to a failed primary surgery, but rather that the wrong procedure was performed for the wrong diagnosis. It should also be remembered that not all cases of anterior instability are due to Bankart lesions alone. Anterior-inferior labral tears are present in 65% to 90% of shoulders (2,4, 5, 6, 7). Other pathology includes Hill-Sachs lesions in 77%, injury to the glenoid rim (including fracture) in 73% (6,8), and glenoid avulsion fractures in 4% of shoulders. Rotator cuff tears are identified in up to 13%, and posterior glenoid labral tears in 10% of shoulders (9). A redundant capsule and deficient subscapularis muscle can also contribute to shoulder instability (5).

If it is determined that the initial diagnosis and treatment were more than likely appropriate, the next step is

to diagnose the current cause for symptoms. It is helpful to determine whether the complaints are acute and the result of a recent significant trauma, or whether the shoulder has never felt quite right since the initial surgery. Complaints of pain versus instability are important to differentiate. Instability symptoms may be due to failure of the initial repair, whereas pain may be due to arthrosis or concomitant rotator cuff pathology. Differentiating these conditions can typically be accomplished through a careful physical examination and appropriate radiographs. The single most important finding for recurrent instability on examination is the presence of the apprehension sign.

to diagnose the current cause for symptoms. It is helpful to determine whether the complaints are acute and the result of a recent significant trauma, or whether the shoulder has never felt quite right since the initial surgery. Complaints of pain versus instability are important to differentiate. Instability symptoms may be due to failure of the initial repair, whereas pain may be due to arthrosis or concomitant rotator cuff pathology. Differentiating these conditions can typically be accomplished through a careful physical examination and appropriate radiographs. The single most important finding for recurrent instability on examination is the presence of the apprehension sign.

Once the diagnosis of recurrent anterior instability has been made, it is essential to obtain the previous operative report whenever possible before deciding upon revision treatment. It cannot be assumed that a revision Bankart operation is indicated for every case. For example, a Bankart alone may not be successful if the initial procedure was a Latarjet or Bristow done in the presence of a large bony Bankart lesion. Choosing a revision Bankart operation will also not be successful if the cause of recurrent instability is a subscapularis rupture or insufficiency. Therefore, it is useful to know whether the subscapularis was divided during the initial surgery or split along its fibers, which would be less likely to cause this complication.

The initial postoperative course can also provide useful information regarding the patient’s current condition. Questions should be asked about the rehabilitation program that was performed. An overly aggressive program may be an indication that the surgical repair has been disrupted. Failure to do appropriate range-of-motion exercises in a timely fashion may have more to do with loss of motion in a patient than an overly tight surgical repair. Asking whether the patient ever experienced an abrupt change in his or her status during the course of the rehabilitation program, and what exercises they were doing at the time, can also yield helpful information. Issues related to voluntary instability are also pertinent (10).

NONANATOMIC AND HISTORICAL REPAIRS

The surgeon should be familiar with a variety of historical instability procedures and nonanatomic repairs (11). Specific complications are inherent to specific nonanatomic repairs. This knowledge will allow a better understanding of the pathology that might be encountered at revision surgery and allow appropriate preoperative planning to be performed. In rare cases, some of these operations may be used as the revision procedure itself to salvage a specific earlier repair.

For example, the Bristow procedure scars the subscapularis tendon and muscle. This typically causes a loss of external rotation up to 23 degrees (12) and decreases internal rotation of the shoulder. Athletes who require overhead use of their arms are frequently unable to return to high-performance levels due to the alteration of normal anatomy (13,14). The typical complications following the Bristow procedure include recurrent painful anterior instability, articular cartilage damage, nonunion of the coracoid bone block, loosening and migration of hardware (15), neurovascular injury (especially musculocutaneous nerve), and posterior instability (16). Revision of a failed Bristow procedure is very difficult due to the significant scarring that occurs. Consider the need for bone grafting, hardware removal, and soft tissue repair, if necessary.

In the Putti-Platt procedure, a vertical incision is made in the subscapularis tendon and capsule. The tendon and capsule are then shortened by overlapping them in a “pantsover-vest” fashion. Intra-articular pathology (such as labral tears) is not repaired. The Putti-Platt procedure can result in complications such as limitation of external rotation and degenerative arthritis (17). Patients are typically unable to return to competitive throwing. Common revision issues include the need for soft-tissue release, tendon lengthening, or the treatment of various stages of arthritis.

The Magnuson-Stack procedure (18) involves lateral transfer of the subscapularis tendon from its insertion on the lesser tuberosity to the greater tuberosity. The procedure, like the Putti-Platt, is designed to restrict external rotation without addressing any underlying pathology that causes shoulder instability. Recurrence rates range from 2% (19) to 17% (20), whereas loss of external rotation ranges from 10 to 30 degrees (19,20). Glenohumeral arthritis and muscle weakness are reported as well (21,22).

RECURRENT INSTABILITY

Recurrent instability following an anterior shoulder stabilization procedure must be assessed carefully and systematically. For example, following a previous Bankart operation, a new trauma can cause a disruption of a well-performed capsulo-labral repair done for correctly diagnosed anterior instability. Alternatively, the new trauma may not disrupt the prior repair but rather result in a new cause for instability, such as a subscapularis rupture or bony Bankart injury. If the previous repair was not performed adequately, a relatively minor trauma can also lead to recurrent instability. While interviewing the patient, it may become clear that preoperative symptoms were never eliminated. This is an indication that either an incorrect diagnosis was made initially or the correct procedure was not performed. Lastly, a strong repair may have been done for the wrong initial diagnosis, such as an anterior Bankart repair done in the presence of a missed posterior instability.

Recurrent instability following anterior stabilization of

the shoulder occurs in 0% to 11% of patients (4,23,24). The most common causes for failure are: (a) an avulsed anterior capsulo-labral complex from the glenoid rim (unrepaired Bankart lesion or failed initial repair), (b) excessive capular laxity, (c) an enlarged “rotator interval,” and (d) failure to diagnose the correct direction(s) of instability. Other causes include large osseous defects that are not treated at the time of the initial stabilization (25), the presence of a Hill-Sachs lesion, reduced humeral head retroversion (26), excessive glenoid cavity retroversion, avulsion of the anterior capsule from its lateral humeral attachment (HAGLlesion) (27), unrecognized scapular winging, and a ruptured, scarred, or weakened subscapularis muscle or tendon.

the shoulder occurs in 0% to 11% of patients (4,23,24). The most common causes for failure are: (a) an avulsed anterior capsulo-labral complex from the glenoid rim (unrepaired Bankart lesion or failed initial repair), (b) excessive capular laxity, (c) an enlarged “rotator interval,” and (d) failure to diagnose the correct direction(s) of instability. Other causes include large osseous defects that are not treated at the time of the initial stabilization (25), the presence of a Hill-Sachs lesion, reduced humeral head retroversion (26), excessive glenoid cavity retroversion, avulsion of the anterior capsule from its lateral humeral attachment (HAGLlesion) (27), unrecognized scapular winging, and a ruptured, scarred, or weakened subscapularis muscle or tendon.

Specific guidelines for treatment to correct recurrent anterior shoulder instability after prior treatment have previously been reported by Zarins and Kolettis (28) and Gill et al. (29). The critical element is to make an anatomic diagnosis of the etiology for recurrent instability and then choose a revision procedure that directly addresses the pathology. Often, this diagnosis can be made on history and physical examination, in conjunction with appropriate imaging. Missed instability patterns, especially posterior instability or multidirectional instability, should be specifically investigated on examination. Increased passive external rotation, a positive belly press test, or positive liftoff test suggests disruption of the subscapularis tendon.

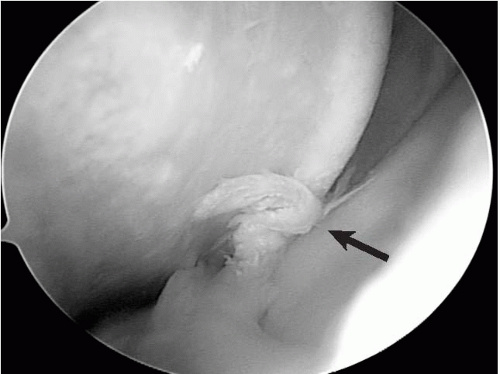

Judicious use of imaging can also elucidate the etiology of recurrent instability. Appropriate use of plain radiographs is very useful to rule out any osseous defects. In particular, the axillary view can give an assessment of the anterior and posterior glenoid rims, the West Point view gives good visualization of the anterior-inferior glenoid rim to better assess the presence of a bony Bankart lesion, and the Stryker notch view can be used to delineate the size of a Hill-Sachs lesion. If bony lesions are suspected, computed tomography (CT) imaging should be performed to quantify the degree of bone loss. Postsurgical changes may make standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) difficult to interpret, although subscapularis tendon ruptures can be confirmed. The use of magnetic resonance arthrography increases the sensitivity of detecting recurrent labral tears. Even if an open approach to revision surgery is preferred, as is often the case, an initial arthroscopic examination can be very useful to make or confirm a diagnosis of a failed prior labral repair or to rule out an associated posterior labral tear, which may indicate an undiagnosed posterior component of the instability. In addition, arthroscopy allows for a dynamic assessment of whether a Hill-Sachs lesion engages the anterior glenoid rim with external rotation, indicating the possible need for either osseous reconstruction, or intentionally preventing the degree of external rotation necessary to engage the defect (Fig. 1-1).

SURGICAL OPTIONS

Some of the etiologies of recurrent instability are relatively straightforward to address. If the diagnosis is made of a recurrent Bankart lesion, then a revision Bankart procedure (either open or arthroscopic) can be performed. However, other etiologies offer more complex challenges.

Osseous defects of either the glenoid or humeral head are often overlooked or undiagnosed. Patients are suspected to have this lesion if they have failed prior instability surgery and/or have had many instability episodes with decreasing force necessary for each episode. Historically, Rowe’s qualitative assessment of one-third glenoid bone loss as a basis for deciding about soft-tissue repair was the surgeon’s best method (6). This might be expected to underestimate the degree of glenoid loss and cause the surgeon to err on the side of a biomechanically weak soft-tissue reconstruction using a conventional Bankart repair technique (30). Burkhart and DeBeer (31,32) observed a failure rate greater than 80% in athletically active individuals who had anterior glenoid erosion treated with arthroscopic Bankart repair. Gerber and Nyffler (33) described a criterion to determine the need for glenoid bone grafting. The authors recommend a bone graft if the length of the glenoid defect is longer than the maximum radius of the glenoid (Fig. 1-2). Other studies have supported this concept (30,34, 35, 36, 37, 38). Preoperative CT imaging of patients suspected of severe glenoid bone loss can identify candidates for glenoid reconstruction preoperatively.

In one study, a 4% (11/262) incidence of severe glenoid insufficiency in the setting of recurrent anterior instability after trauma was reported (25), which was thought to be directly responsible for the patient’s instability. Most of these patients (9/11) had recurrent instability following conventional Bankart repair. Several options are available to address a deficient glenoid rim. The Bristow-Helfet and the Laterjet procedures involve transfer of the coracoid process and conjoined tendon through the subscapularis and onto

the anterior scapular neck (23,39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46). The mechanism of stability is through creation of an anterior bone block, as well as both the passive sling effect and active stabilizing effect of the conjoined tendon. Although these series have reported very satisfactory outcomes with this technique, some have observed significant problems including loss of motion, hardware impingement and loosening, nonunion of the bone graft, and arthritis. Furthermore, revision surgery can be very challenging due to scarring and distortion of the anatomy around the subscapularis muscle and brachial plexus (16). We prefer an anatomic reconstruction of the anterior glenoid rim using tricortical iliac crest bone graft (Fig. 1-3). Excellent results have been reported with this technique, with very few complications (25).

the anterior scapular neck (23,39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46). The mechanism of stability is through creation of an anterior bone block, as well as both the passive sling effect and active stabilizing effect of the conjoined tendon. Although these series have reported very satisfactory outcomes with this technique, some have observed significant problems including loss of motion, hardware impingement and loosening, nonunion of the bone graft, and arthritis. Furthermore, revision surgery can be very challenging due to scarring and distortion of the anatomy around the subscapularis muscle and brachial plexus (16). We prefer an anatomic reconstruction of the anterior glenoid rim using tricortical iliac crest bone graft (Fig. 1-3). Excellent results have been reported with this technique, with very few complications (25).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree