Etiology and Prevention

Since Codman’s initial treatise on the surgical treatment of rotator cuff tears in 1911,

45 improved operative techniques have been responsible for a high success rate, with enduring patient satisfaction.

47,

57,

75,

107,

108,

120,

137,

214,

241 However, recurrent or persistent rotator cuff defects have been reported to occur in 20% to 90% of the cases,

20,

38,

73,

77,

90,

102,

133,

141,

143,

160,

161,

179,

227,

232,

233,

243 with the risk of recurrence increasing relative to the size of the initial tear. The failure rates between arthroscopic and open repairs appear to be equal when the tear is small and involves minimal retraction of the musculotendinous unit. The incidence of failure is highest among elderly patients with chronic and retracted tears involving two or three tendons. Arthroscopic repairs under these conditions represent the highest failure rate in both in vitro and clinical studies,

40,

44,

73,

75,

83,

160,

219,

232 although the gap appears to be closing as arthroscopic techniques continue to improve with failure rates anywhere from 30% to 50% for the large to massive tears.

137 Recently, Millar and colleagues showed improvement in outcomes and re-tear rates using arthroscopic methods versus open methods.

160 However, Bishop and colleagues showed an almost threefold increase in re-tear rates for tears greater than 3 cm done by arthroscopic techniques.

20 Clearly, controversy continues to exist for the best method of treating large to massive rotator cuff tears.

Persistent defects are not necessarily the sine qua non for failure, since the presence of a persistent rotator cuff defect is compatible with a good postoperative result following rotator cuff repair.

38,

57,

73,

77,

133,

143,

232 This process of converting a symptomatic tear into an asymptomatic re-tear is not entirely clear, although it may involve adequate subacromial decompression (SAD), debridement, biceps tenotomy, partial healing of the rotator cuff, and adequate postoperative rehabilitation.

30,

31,

188,

210 The quality of functional results, however, depends on the size of the persistent defect, associated atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles, the integrity of the deltoid and the coracoacromial arch, and the age and functional demands of the patient.

57,

65,

102,

103,

122,

144,

171,

185,

252 Patients with persistent rotator cuff defects will be capable of overhead function when the deltoid is intact and the anterior and posterior portions of the rotator cuff are intact and balanced.

29,

31,

32,

57,

232 However, they will generally complain of fatigue with overhead activities, and limitation in activities that require vigorous or sustained overhead strength, as compared with patients with an intact rotator cuff.

77,

102,

179 Therefore, the goal of rotator cuff repair is long-term restoration of a functional, healed musculotendinous unit. While this may not always be attainable in primary rotator cuff repair, the development of recurrent rotator cuff tears may be minimized through a combination of careful preoperative patient selection, meticulous surgical technique, and attention to appropriate postoperative protection and rehabilitation.

With the understanding that the correlation between postoperative subjective and functional results and anatomic results (i.e., rotator cuff integrity) is variable,

77,

85,

102,

143 outcome studies have begun to focus on patient satisfaction in terms of patient-derived subjective assessments of symptoms and function.

117,

159,

182,

212,

232,

243 Preoperative and surgical variables that are associated with poorer patient satisfaction include older patients, patients with chronic or irreparable subscapularis tears, large to massive supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears, tear retraction, atrophy of the rotator cuff muscles, especially the infraspinatus, and fatty infiltration of the muscle bellies.

47,

80,

82,

85,

88,

107,

117,

149,

182,

185,

204,

214,

229,

243,

250 Objective postoperative variables that are associated with poorer patient satisfaction include diminished and weakened forward elevation, impingement signs, and acromioclavicular joint pain and tenderness. Subjective variables associated with poorer patient satisfaction include persistent pain, functional impairment, and work disability.

182,

250 Numerous studies have shown that fat infiltration and muscle atrophy are not reversible after surgery and are positive predictors of re-tear and decreased functional outcomes.

81,

83,

85,

90,

141,

161,

243 In a 13-year follow-up study on the results of rotator cuff repair in patients under 50 years of age, Sperling and colleagues have shown that while patients experience significant long-term pain relief following repair, the functional results are inferior to those seen in a mixed-age population.

229 A prospective longitudinal analysis of rotator cuff repairs by Galatz and colleagues indicated that as patients advance in age, their functional requirements decrease, and therefore satisfaction does not decline.

75 This was also found by Oh and colleagues, who showed that functional outcomes were improved in older patients after rotator cuff repair despite decreased rotator cuff integrity when compared with a younger population.

185Associated risk factors for recurrent tears include advanced age, tear size, chronicity and atrophy, poor tendon quality, fatty infiltration of the muscle belly, poor bone quality, inappropriate rehabilitation, inadequate SAD, smoking, steroid injections, and diabetes.

59,

77,

90,

102,

175,

184,

185,

204,

233Preoperative variables exist which will have a bearing on the ability to obtain long-term tendon-to-bone healing. In the presence of an acute rotator cuff tear, the biologic potential for healing appears greater when the repair is performed within 3 weeks of injury.

12,

101 In long-standing tears or delayed repairs, muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration may develop, which do not appear to be reversible after rotator cuff healing, and have a negative effect on the outcome following rotator cuff repair.

85,

141,

220 These changes may be graded using computed tomographic scanning or magnetic resonance imaging, and increase with elapsed time from the tendon rupture.

72,

101,

161,

233,

259 Additionally, chronic retraction and scarring of the musculotendinous unit may preclude the surgeon from obtaining an adequate tendon-to-bone repair. Therefore, in the presence of an acute or acute-on-chronic rotator cuff tear with retraction of the tendon, early repair is more likely to result in long-term tendon-to-bone healing as compared with late repair. This potential advantage should be considered in the context of appropriate patient selection criteria such as age, physical demands, comorbidities (diabetes and smoking), and motivation (willingness to comply with rehabilitation), prior to recommending surgical intervention.

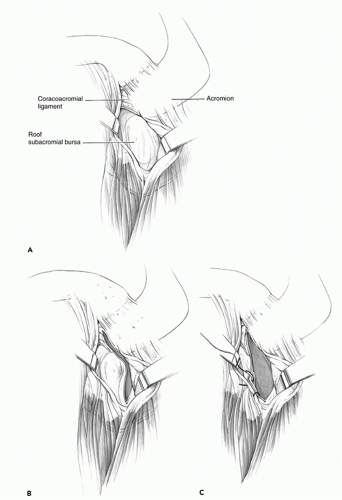

The surgical principles that most likely reduce postoperative recurrent tears or persistent defects include adequate mobilization of the tendon to the greater tuberosity, preparation of the tendon and bone interfaces, and secure fixation of

the tendon to bone. These principles hold true for all repair methods. The superficial surface should be free from the overlying deltoid, acromion, subdeltoid bursa, scapular spine, coracoid, and the trapezius muscle. Capsular releases are frequently required to release the tenodesis effect of the underlying capsule.

261 Interval releases may also be required to allow full excursion of the contracted tendon.

16,

171,

172 and

173 A thorough understanding of the various tear configurations will enable the surgeon to perform the proper releases, repair longitudinal tears in a convergent manner, and repair the tendon to bone with minimal tension. A repair that has been overly tensioned will eventually fail.

32 Inability to adequately mobilize the tendon may be due to substantial intramuscular scarring and the development of fatty atrophy. Tendon convergence and advancement methods as well as the management of irreparable rotator cuff tears have been discussed in previous chapters.

Debridement of the greater tuberosity, along with abrasion of the cortical surface at the proposed site of tendon attachment, may enhance tendon healing. While open rotator cuff techniques often include the creation of a shallow cancellous trough, most arthroscopic techniques repair the tendon to the cortical surface of the greater tuberosity. The rates of tendon healing between a shallow cancellous groove or trough, and a cortical bone surface appear to be equal.

230 Therefore, complete removal of the cortical surface of the humeral attachment site is probably not necessary.

158 While excessive debridement of the tendon edges is not necessary or advisable, excision of the friable, necrotic edges will reveal a healthy tendon edge for suture placement.

87 The majority of rotator cuff repair failures occur when the suture pulls through the tendon.

54 Tendon grasping suture techniques such as the Mason-Allen technique provide excellent pullout strength and presumably a more durable repair during open rotator cuff surgery, as compared with simple or mattress sutures.

40,

83,

222 The holding strength of arthroscopically tied horizontal mattress sutures appears to be higher than that of the Mason-Allen suture. The massive cuff stitch, which includes a horizontal mattress stitch that is reinforced with a vertical loop, may act in a manner similar to that of the Mason-Allen suture technique.

146 While the holding strength that is required for successful tendon-to-bone healing is unknown, data exist supporting the superior holding strength of open transosseous techniques as well as for arthroscopic fixation using bone anchors.

40,

44,

160,

161,

205 As a result, some authors continue to prefer open repair methods in order to reduce the risk of re-tear, especially in the case of large to massive rotator cuff tears.

The advent of improved suture anchoring devices has led to their widespread acceptance and use in rotator cuff repair procedures. The advantages of suture anchors include the ease of use, decreased operating time, and decreased surgical exposure and morbidity. While most rotator cuff repair failures occur at the tendon— suture interface, anchors may subside without actually pulling out of the bone, leading to gap formation, poor tendon-to-bone healing, and rotator cuff repair failure.

32,

33,

37,

40,

44,

146,

155,

158,

161,

222,

235 Anchor placement depends on the type of bone in which they rely for fixation, and pullout strength varies according to the bone quality of the humeral head. Tingart and colleagues have shown that the higher bone mineral density in the proximal—medial and proximal anterior regions of the greater tuberosity (i.e., closer to the articular surface) is associated with increased pullout strength of suture anchors.

235 While suture anchors may represent an attractive option in young patients with high bone density, like any fixation device in orthopedic surgery, bone stock and strength remain major limitations and caution should be exercised among patients with poor bone quality such as postmenopausal women, smokers, and elderly patients, as these devices may not provide adequate pullout strength for rotator cuff repair. Under these circumstances, passing sutures through bone tunnels and tying the sutures over a lateral bone bridge may provide superior strength. This may be augmented with a thin plate or button to provide additional resistance to pullout of the sutures.

37 Recently, a novel arthroscopic technique has been developed that incorporates the advantages of both a true transosseous technique and an arthroscopic approach to the shoulder. Short- and long-term studies are necessary to fully evaluate this technique.

Proper postoperative protection and rehabilitation play an important role in preventing postoperative recurrent or persistent rotator cuff defects. Early postoperative mobilization has been a subject of increased debate and controversy. Although many surgeons have advocated for early passive range of motion after rotator cuff surgery in the past,

126,

131,

171,

211 recent in vitro studies by Peltz and colleagues

194,

195 showed that early passive range of motion in a rat model was associated with increased joint stiffness. The same group has also shown that while there is an increase in stiffness at early time points after immobilization, this was transient with a resolution of range of motion in the immobilization group. A recent in vitro study has shown an improved tendon biomechanics when activity and exercise was limited in a rat model.

195 The delicate balance between tendon healing and postoperative stiffness was recently addressed in a study by Parsons and colleagues who found that 6 weeks of immobilization had no effect on range of motion at 1 year.

189 Immobilization typically lasts 4 to 6 weeks with patients who return to their postoperative visits exhibiting increased stiffness undergoing initiation of simple passive exercises of external rotation and pendulum exercises. Larger tears that have been repaired will typically be managed with increased immobilization and a greater tolerance for immediate postoperative stiffness. Immobilization is usually in a simple sling; however, in larger posterior-superior tears, the protective orthosis should place the arm at the side in a small amount of abduction in order to allow the tendon to heal under a minimum amount of tension.

111,

206 Chronic or massive tears may require the use of a larger abduction pillow or orthosis, depending on the amount of tension that is observed at the time of surgery. Passive motion exercises should be instituted at 4 to 6 weeks with active motion exercises initiated between 8 and 10 weeks, avoiding resisted strengthening and isokinetic exercises until 3 months following repair. Increases in resistance are continued until 6 months at which time the patient can be allowed to return to full activity. The initiation of early active motion and the use of weights in the early postoperative period have been associated with failure of the repair.

175

Evaluation

Since the risk of recurrent rotator cuff tears is highest among elderly patients with chronic tears involving two or more tendons,

102 the index of suspicion for this complication should be high when these patients complain of persistent pain and functional impairment. Physical findings vary according to the size and location of the tear, the integrity of the coracoacromial arch, and the presence of soft tissue contracture. Lack of both active and passive elevation is more likely to represent capsular contracture rather than residual rotator cuff insufficiency. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to determine the presence and clinical relevance of recurrent rotator cuff tears

in a stiff shoulder. Once the soft tissue contracture has been excluded or corrected, the physical findings associated with a recurrent rotator cuff tear will become more apparent.

Symptomatic patients will have subacromial crepitance, weakness on isolated muscle testing, and will often demonstrate a positive “lag sign” on physical examination.

112 When pain appears to be a limiting factor during strength testing, a subacromial lidocaine injection will usually alleviate a significant amount of associated pain, and increase the reliability of the examination. Recurrent defects in the posterior-superior portion of the rotator cuff (supraspinatus and upper infraspinatus tendons) generally demonstrate weakness of arm abduction and weakness of external rotation with the arm at the side. This external rotation weakness generally improves when the arm is brought into 90 degrees of elevation in the scapular plane. Conversely, a tear involving the posterior-inferior portion of the rotator cuff (infraspinatus and teres minor tendons) will usually demonstrate external rotation weakness with the arm at the side as well as in 90 degrees of elevation in the scapular plane. External rotation lag signs refer to the inability of the patient to actively maintain maximal external rotation of the arm when it has been passively placed in this position by the examiner. Positive external rotation lag signs with the arm at the side, or with the arm at 90 degrees of elevation in the scapular plane, indicate recurrent defects in the posterior-superior and posterior-inferior rotator cuff, respectively. External rotation lag signs at any level of abduction are not particularly reliable in the detection of weakness associated with an isolated supraspinatus tear.

121 Abduction of the arm in the scapular plane, with the elbow extended and the humerus internally rotated, is generally accepted to represent supraspinatus function.

112,

126 Therefore, weakness in this position may indicate a recurrent or persistent tear of the supraspinatus.

Subscapularis insufficiency results in increased passive external rotation of the shoulder as well as weakness of terminal internal rotation. Detection of a recurrent defect requires careful isolation of the muscle from other internal rotators of the shoulder girdle.

93 The internal rotation lag sign represents the inability of the patient to maintain the dorsum of the hand away from the mid-lumbar spine after it has been passively placed in this position of maximal internal rotation by the examiner. Similarly, the lift-off test is sensitive for detecting subscapularis insufficiency and describes the inability of the patient to actively lift the dorsum of the hand away from the lumbar spine.

82,

112 These tests require full passive internal rotation in order to place the arm in the appropriate position. In the presence of posterior capsular contracture, the abdominal compression test appears to be as specific as the lift-off test in assessing subscapularis insufficiency.

236 The test is positive when the patient is unable to maintain the flexed elbow anterior to the coronal plane of the body while simultaneously maintaining the palm of the hand compressed against the abdomen. Scapular protraction is often difficult to control and will interfere with the performance of this test. When this occurs, it may be easier to control scapular protraction with the patient in the supine position.

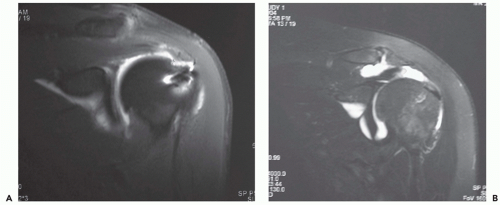

The suspected diagnosis of a recurrent rotator cuff tear may be confirmed with ultrasonography, arthrography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

38,

77,

96,

141,

148,

161,

186,

243 The presence of postsurgical artifact will interfere with the interpretation of imaging studies, and the diagnostic criteria for a full-thickness recurrent tear are more stringent than that for a shoulder that has not undergone surgery. Magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) or ultrasonography can be used. However, our preferred imaging modality is MRA because it provides information regarding tear size, muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration, and concomitant biceps and labral pathology. While the clinical relevance of minor tendon signal abnormalities is uncertain,

165 a well-defined tendon gap that is traversed by fluid is a reliable indicator of a persistent or recurrent rotator cuff defect (

Fig. 1-1).

96,

179,

233