Complications of Anterior and Posterior Open Approaches to the Lumbar Spine

Raj D. Rao

Peeush Singhal

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar spinal disorders are the most frequent cause of disability related to the spine. In most cases, nonsurgical care will successfully alleviate symptoms. Surgery is necessary when the pain persists and is intractable, or when neurologic findings are progressive. This chapter will review complications of the anterior and posterior approach to the lumbar spine, and discuss common techniques that help reduce the incidence of these complications.

A thorough understanding of the anatomy, meticulous preoperative planning, and careful surgical technique will obviate most complications. As in almost all cases of spine surgery, adequate visualization helps minimize surgical time and reduce complications. Appropriate lighting and magnification have now become routine. Understanding the anatomic planes, placement of retractors in the appropriate position, and maintenance of a relatively dry operative field helps optimize the surgical procedure.

POSITIONING THE PATIENT

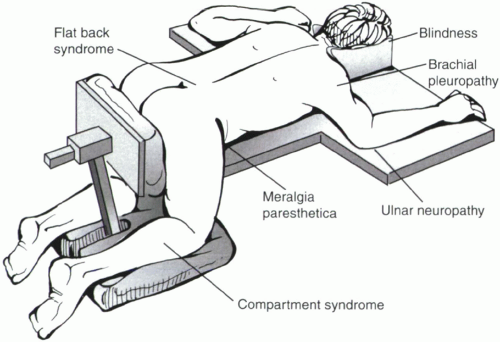

Appropriate and careful positioning is an integral component of spine surgery. While the focus of the surgeon is to obtain maximal access to the lumbar spine, a systematic protocol must be developed to protect the head, neck, and extremities during the surgical procedure. Many elderly patients undergoing spine surgery have thin, friable skin and vulnerable bony prominences. Adequate padding must be placed around all bony prominences to avoid skin breakdown.

Responsibility for positioning of the head is generally assumed by the anesthesiologist, who ensures the endotracheal tube is securely positioned. The spine surgeon should nevertheless be aware of potential consequences of inappropriate positioning. Pressure breakdown from foam headrests can occur over the nasal cartilages or chin during lengthy operations.

Blindness is a feared but rare complication of spine surgery in the prone position (1,2,3). Direct pressure over the eyeball with ischemic optic neuropathy or central retinal artery occlusion is a postulated mechanism. Blindness can also result from systemic hypotension during the operative procedure, massive blood loss, or preexisting microvascular disease, including diabetes mellitus. Headrests are generally to be avoided in favor of a foam cushion with cut-outs for the eyes, nose, and chin, and the anesthesiologist should repeatedly examine these organs during the operation to ensure that they continue to stay free of pressure.

Nerve palsies result from undue pressure on the course of peripheral nerves, especially when they lie superficially or tethered against bony prominences. Particular attention should be paid to positioning the upper extremities. Ulnar nerve injury at the cubital tunnel is frequently reported, and the medial elbows should be well-padded with foam cradles. Brachial plexus palsy may result from prolonged abduction of the shoulders beyond 90 degrees. Brachial plexus or axillary nerve injury can also result from allowing the unsupported shoulder to droop, or from excessive pressure in the axilla. In the lower extremities, injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerves or femoral nerves can result from pressure on the iliac crest or proximal femur, particularly in heavy individuals, or with inadequate padding of the pelvic or femoral support pads for a patient in the prone position.

The patient is positioned either flat prone or in the knee-chest position when posterior surgery is planned (Fig. 9.1). In either position, keeping the abdomen free of pressure will decrease intra-abdominal venous pressure and result in reduced intraoperative blood loss. Positioning in the knee-chest position reduces lumbar lordosis, providing greater access to the interlaminar space for decompression of neural structures. However, fusion of the spine should not be carried out in this position to avoid pain from a flat-back syndrome. Prolonged knee-chest position can result in decreased blood flow to the lower extremities, compartment pressure elevations in the leg, and pressure breakdown of the skin over the tibial crest (4).

Deep venous thrombosis remains a significant perioperative complication following spine surgery, with a reported incidence between 1.0% and 2.4% (5,6). Chemical anticoagulation is generally contraindicated in the immediate period following spine surgery to minimize the risk of epidural bleeding, and mechanical prophylaxis remains the technique of choice. Thromboembolic stockings and sequential compression devices should be used intraoperatively and have been shown to decrease the rate of deep venous thrombosis. Care should be taken to ensure that the crest of the tibia does not directly lie over these devices when the patient is in the prone position, as this can lead to skin necrosis in the region of the tibial crest.

POSTERIOR APPROACHES TO THE LUMBAR SPINE

Posterior approaches to the lumbar spine are very familiar to the surgeon involved in the management of lumbar spinal disorders. The specific approach chosen will vary with the location and type of pathology and is either through a midline approach, paraspinal approach as described by Wiltse, or a transforaminal endoscopic approach. While some complications are common to all posterior approaches, others are specific to a particular approach. As with any surgical exposure, adequate lighting, magnification, and hemostasis are required for proper visualization and minimization of complications.

Approaches recently described as “minimally invasive” attempt to minimize the muscle stripping associated with the posterior approach. These approaches generally approach the spinal column through a muscle-splitting approach in the paramedian plane, either dissecting through muscle or through sequential dilatation that, in theory, spreads muscle fibers around the portal. Specialized retractor systems or tubular access portals allow visualization in the depths of the incision while limiting the length of the skin incisions. The anatomic structures at risk, and the potential complications, are similar with both open and minimally invasive posterior approaches. The decreased visualization with the newer techniques increases the likelihood of adverse events, particularly during the learning curve for

the surgeon. Dealing with complications is a greater challenge through these limited incision techniques.

the surgeon. Dealing with complications is a greater challenge through these limited incision techniques.

Neurologic Injuries

Radiographs of the lumbar spine should be carefully reviewed preoperatively to determine whether the patient has spinal dysraphism such as such spinal bifida occulta, or otherwise large interlaminar spaces. Iatrogenic durotomy can occur in these patients during the process of elevating the paraspinal muscles off the posterior bony elements, with either the electrocautery or the periosteal elevator. Similar care is also necessary in cases of prior laminectomy. Ensuring that the tip of your instalment can feel bone will avoid inadvertent entry into the canal and injury to the dura or nerves.

Bony resection for a laminectomy or laminotomy is generally carried out with Kerrison rongeurs or motorized burrs. Residual bony spikes can lacerate the dura and should be smoothed out with a rongeur or curette. The foot plate of the Kerrison rongeur should be placed parallel to the thecal sac or nerve root to prevent inadvertent laceration. In addition, the foot plate must be inserted flush with the undersurface of the bone to minimize the risk of trapping a fold of dura within the jaws. Cottonoid pledgets are generally inserted between the dura and the overlying structures to avoid inadvertent dural tears. In patients with high-grade lumbar stenosis, insertion of large Kerrison rongeurs or cottonoid pledgets can further compromise the spinal canal, leading to neurologic deficits. In these cases, a burr is used to thin the laminar bone and curettes can then be used to remove the remaining bone. This avoids insertion of instruments into the canal, further compromising an already narrowed spinal canal. Leaving the ligamentum flavum and epidural fat layers intact during the initial phases of laminectomy can in some cases provide an additional layer of protection during the initial laminectomy. These tissues can later be easily separated from the dura and removed.

With chronic and severe lumbar spinal stenosis, the dura is occasionally adherent to the overlying soft tissue or bone. This must be recognized early to minimize the likelihood of durotomy. The adhesions are released with angled curettes or soft tissue dissectors prior to bone or ligamentum flavum removal. Movement of the dura during bone or ligamentum removal should raise suspicion for such adhesions. In some cases, it may be preferable to leave a small section of adherent ligamentum flavum attached to the dura, as long as this does not mechanically compress the thecal sac.

The next stage of the decompression generally focuses on the lateral canal, and attention is paid at this step to avoid nerve root or dural injury. Care should be exercised to avoid excessive or prolonged retraction of the thecal sac, to minimize the risk of a “battered root syndrome” or other neurologic deficit. There should be no attempt at retraction of the spinal cord or conus medullaris in the upper lumbar spine. The nerve root will occasionally resemble a disc when it is stretched taut by an underlying disc herniation. Prior to incising what appears to be annulus, the lateral edge of the nerve root and thecal sac must be clearly identified. If difficulty is encountered in locating the nerve root, more lamina is resected until the medial wall of the pedicle is located. The exiting nerve root is noted along the inferomedial aspect of the corresponding pedicle. Congenital variations in nerve root anatomy can lead to a missing nerve root at a level, and occur with an incidence of 2% to 14% in lumbar spine surgery (7).

When an intertransverse fusion is planned, the dissection will extend ventrally past the facet joint to expose the transverse processes. It is important during this dissection to identify and avoid violation of the intertransverse membrane. The ventral rami of the nerve roots lie anterior to this membrane after exiting the neuroforamen. Blunt elevation of the muscles off the membrane, combined with electrocautery of residual muscle fibers directly on the bone of the transverse process, allows safe exposure of the area.

Vascular and Visceral Injuries

Substantial blood loss can occur with posterior lumbar approaches if proper surgical technique is not adhered to. Subperiosteal elevation of the paraspinal musculature minimizes laceration of large intramuscular vessels. During mobilization of the thecal sac and nerve roots, significant bleeding occasionally occurs from the epidural venous plexus. In these cases, bleeding should be controlled with thrombotic agents or bipolar cautery. Unipolar cautery should be avoided in the canal. Ensuring that the abdomen is free during positioning of these patients can reduce the back pressure within these veins and reduce intraoperative bleeding. Careful exposure of the region between the pars interarticularis and facet joint will allow early identification and cauterization of the segmental artery just lateral to the pars. These segmental arteries are branches from the aorta, fourth lumbar artery, middle sacral artery, internal iliac artery, and the iliolumbar artery. The arteries travel dorsally in between the facet joint and just lateral to the pars interarticularis (Fig. 9.2).

Injury to large vessels anterior to the lumbar spinal column can occur during discectomy from inadvertent passage of instruments beyond the anterior longitudinal ligament (8,9). Visceral injuries occur rarely with the posterior approach. Injuries to the bowel, pancreas, and ureters have been reported with violation of the anterior longitudinal ligament during lumbar discectomies (10). Entry into the retroperitoneum can occur if dissection is carried anterior to the intertransverse membrane.

Miscellaneous Complications Associated with the Posterior Lumbar Approach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree