Complex Regional Pain Syndromes

General Information

Arm injuries produce pain. This is not surprising given the density of sensory innervation of the arm. Not only will the patient experience pain from skin incision or laceration, but also from indirect (swelling or traction) and direct (contusion or laceration) of deeper innervated structures, including individual named and unnamed nerves.

Difficulty arises when pain appears greater than that expected from the observed injury. This phenomenon of “pain out of proportion to the observable injury” is often referred to as “complex regional pain syndrome.” Unfortunately, this term is imprecise and cannot be universally defined. Some agreement exists that to be considered classic complex regional pain syndrome the patient should exhibit:

Pain out of proportion to the provable injury

Measurable stiffness of joints in the affected region

Observable vasomotor difference in the affected area

Diagnostic Criteria

History

The typical patient with complex regional pain syndrome may not exist; however, some characteristics are seen commonly:

The patient will likely recall an injury. The injury may not have been severe and no fracture, laceration, or other observable injury may have been noted. The onset of “true complex regional pain syndrome” in the absence of a recalled injury is decidedly uncommon. The physician should detail the recalled injury exactly as the patient states. In work or litigation scenarios, the

physician should delineate the relation of activity to any aggravation of symptoms.

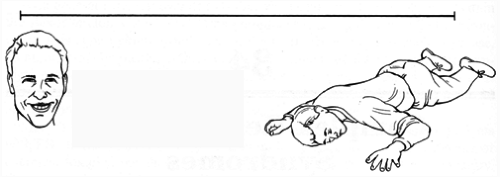

FIG. 1. Visual analog pain scale. The patient is asked to mark the location and volume of the pain. This scale is completed before each visit.

The injury may have been “small.” Management of the injury is often unremarkable.

Women develop this condition more often than men.

This condition rarely occurs in children.

Other factors, such as ongoing addictions (nicotine, prescription drugs, street drugs, ETOH), past history of addictions, involvement in litigation, history of ipsilateral injuries, and current work status should be recorded. No specific past treatment is associated with the onset of complex regional pain syndrome; however, the use of external fixateurs may have a higher than average rate of pain syndrome development when compared with internal fixation for the same fracture type.

A useful method of assessing the degree of pain experienced by a patient is a visual analog scale (VAS pain scale) (Fig. 1). Having the patient complete this tool after each manipulation assists the physician in assessing the effectiveness of treatments.

Physical Examination

Complex regional pain syndrome can involve one or many joints (Fig. 2). The patient’s whole extremity should be examined, beginning with the base of the skull to include the C-spine, shoulder, upper arm, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand.

Palpation will confirm the preceding visual findings and should not reveal any specific mass, lymph node enlargement, swelling consistent with abscess or cellulitis, or bone or joint instability. Examination of joint motion or stability, tendon, nerve, and vessel function should also be within the range of expected

outcome for treatment of a specific injury. Substantial deviation from expected outcome may indicate that the patient’s pain is the result of undertreatment or incomplete treatment of the original injury rather than complex regional pain syndrome (Fig. 2B).

outcome for treatment of a specific injury. Substantial deviation from expected outcome may indicate that the patient’s pain is the result of undertreatment or incomplete treatment of the original injury rather than complex regional pain syndrome (Fig. 2B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree