This article discusses several issues related to therapies that are considered “complementary” or “alternative” to conventional medicine. A definition of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) is considered in the context of the evolving health care field of complementary medicine. A rationale for pain physicians and clinicians to understand these treatments of chronic pain is presented. The challenges of an evidence-based approach to incorporating CAM therapies are explored. Finally, a brief survey of the evidence that supports several widely available and commonly used complementary therapies for chronic pain is provided.

Key points

- •

Complementary therapies are widely used among chronic pain populations.

- •

Physicians and clinicians who treat chronic pain should inquire about and respect the use of complementary therapies.

- •

To enhance an effective therapeutic relationship, clinicians should be able to discuss complementary medicine use nonjudgmentally and in light of the scientific evidence regarding effectiveness and potential for complications.

- •

There is evidence that supports the effectiveness of many complementary therapies.

Introduction

This article discusses several issues related to therapies that are considered “complementary” or “alternative” to conventional medicine (CM). A definition of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) is considered in the context of the evolving health care field of complementary medicine. A rationale for pain physicians and clinicians to understand these treatments of chronic pain is presented. The challenges of an evidence-based approach to incorporating CAM therapies are explored. Finally, a brief survey of the evidence that supports several widely available and commonly used complementary therapies for chronic pain is provided.

Introduction

This article discusses several issues related to therapies that are considered “complementary” or “alternative” to conventional medicine (CM). A definition of “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) is considered in the context of the evolving health care field of complementary medicine. A rationale for pain physicians and clinicians to understand these treatments of chronic pain is presented. The challenges of an evidence-based approach to incorporating CAM therapies are explored. Finally, a brief survey of the evidence that supports several widely available and commonly used complementary therapies for chronic pain is provided.

Emergence of complementary and alternative medicine

Book One of Paul Starr’s 1982 seminal work, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, documents the rise of organized medicine to a position of dominance and hegemony over health care. Although this transformation depended on increased emphasis on education, science, and research, it also fostered an explicit proscription of traditions, histories, and practices of many competing health care disciplines.

At the turn of the twentieth century, American medical practice had just emerged from traditions of heroic medicine that had long coexisted with more moderate, less invasive therapies promoted by William Buchan (domestic medicine), Samuel Hahnemann (homeopathy), Samuel Thompson (naturopathic medicine), and Daniel D. Palmer (chiropractic).

Seeing a challenge to medical dominance, organized medicine, through the agency of the American Medical Association (AMA), began a purge of homeopaths in their ranks, disparaged herbalists, midwives, chiropractors, and other nonmedical professionals. For example, AMA opposition to chiropractic care persisted well into the twentieth century until the final resolution of Wilk v. American Medical Association in 1990 that led to the disbanding of the AMA Committee on Quackery, which had the explicit purpose to “contain and eliminate” the chiropractic profession.

Despite ongoing efforts to marginalize these alternate and competitive healing traditions, many of them persisted and even flourished. For the most part, these streams of nonmedical practice went unnoticed by mainstream medicine until the Eisenberg 1993 article in New England Journal of Medicine . In that survey study, Eisenberg observed that 34% of survey respondents reported using one or more “unconventional” therapies, and about one-third of those saw a provider of the therapy. He went on to extrapolate from the survey data to estimate that Americans made 425 million visits to unconventional medicine providers in 1990, a number that exceeded visits to all US primary care physicians at that time. Further estimates were of $13.7 billion spent on unconventional care. Eisenberg’s “discovery” of the magnitude of health care occurring outside of the medical mainstream of physician offices, clinics, and hospitals caught the attention of many.

Terminology: what is “complementary and alternative medicine”?

Despite its prevalence, cost, and patterns of use, a definition of “complementary and alternative medicine” has been problematic. The Eisenberg study used the term “unconventional medicine,” which they defined as “medical interventions not taught widely at U.S. medical schools or generally available at U.S. hospitals. Examples include acupuncture, chiropractic, and massage therapy.”

Although Eisenberg’s definition was perhaps accurate in 1993, by 2003, 98 US medical schools included CAM-related curricula. In the second decade of the 2000s, acupuncture, chiropractic therapy, and massage therapy can be found in hospitals across the United States. A 2010 survey of US hospitals found that 42% of respondents offered one or more CAM services, most commonly massage therapy and acupuncture. Chiropractic care is provided at 47 major Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities across the United States. Chiropractic therapy is available in many US hospitals.

“Complementary” medicine and “alternative” medicine have different meanings. In addition to Eisenberg’s “unconventional medicine,” other terms are often applied to the field as well to integrative medicine, holistic medicine, and others. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) is a center in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that was created by Congress in 1998. The mission of the Center “is to define through rigorous scientific investigation, the usefulness and safety of complementary and alternative medicine interventions and their roles in improving health and health care.” NCCAM acknowledges the ambiguity surrounding the definitions of these diverse health care practices and offers a summary of the various terms presented in Table 1 . NCCAM now endorses the use of “complementary health approaches” to define the field. All of these terms are contrasted with “conventional,” “biomedical,” “allopathic,” and “mainstream” medicine as practiced by medical (MD)/osteopathic (DO) physicians and their allied professionals, such as nurses and physical therapists. This article uses the term “complementary medicine” to refer to health care clinicians, practices, and interventions that are usually distinct from conventional medical care. Patients use these approaches along with, or complementary to, their conventional medical care.

| Alternative medicine | Used in place of CM |

| Complementary medicine | Used together with CM |

| Integrative medicine | Usually practiced by conventionally trained physicians, integrative medicine combines mainstream medical therapies and CAM therapies |

| Integrated medicine | Typically provided by teams of conventional and CAM clinicians |

| Holistic medicine | Considers body, mind, and spirit in health and healing. |

How is complementary medicine different?

There clearly are differences between health care available in physician offices, clinics, and hospitals and interventions provided by complementary medicine practitioners. There are 3 features of complementary medicine that distinguish it from CM. Complementary therapies are individualized to each patient. Complementary medicine providers almost universally incorporate a philosophy of health that emphasizes and leverages an innate capacity for healing in every individual. Finally, complementary medicine tends to acknowledge the existence of properties of living systems that are resistant to understanding by contemporary reductionist scientific methods of inquiry that inform CM.

These distinguishing features present significant challenges to research and assembling meaningful evidence. They also create opportunities to develop more effective, efficient, and humanizing care for a very difficult population of patients, such as those with chronic pain. A recent observation by Cicerone on evidence-based practice and the limits of rational rehabilitation points out that “…we need to acknowledge the subjective meanings of illness and disability to the patients we serve. Any efforts to build our practice based on the best available systematic evidence are unlikely to succeed unless we include patients’ values and beliefs and incorporate this perspective into our rehabilitation research. This aspect of evidence-based rehabilitation raises important questions about our fundamental roles and how we will choose to practice and define our field in the future.”

Individualized treatment is a hallmark of most complementary therapies. For example, an acupuncture practitioner may evaluate 2 patients, both with the same CM diagnosis, but develop 2 radically different treatment plans based on the Oriental medicine examination findings and assessment. This approach seems to work well for patients. Studies of patients who obtain care from complementary medicine practitioners reveal high levels of satisfaction with the practitioners and the outcome of the therapies. These providers spend time with their patients; they are successful in endorsing patients’ complaints and in explaining to patients the nature of their health problems. Treatment planning tends to be more of a collaboration between therapist and patient than is often experienced in CM practice. Interventions are developed that are consistent with each patient’s expectations, needs, and preferences. Individualized treatments, however, pose significant threats to the validity of typical randomized controlled clinical trial methodology.

Philosophy of care is not something that most CM practitioners ponder extensively. Health care philosophic discourse underlies many CAM therapies. Chiropractic, for example, contains an extensive literature that can loosely be described as “philosophy.” Beginning with the founder, D.D. Palmer, chiropractic thinkers have historically focused not so much on the rational scientific underpinnings of this healing art, but on the art itself. “Innate Intelligence” is posited by Palmer and his successors as a fundamental life force that, when fully expressed without interference, the ultimate expression of health occurs, naturally and without need of intrusion from outside agents. In this chiropractic philosophic world view, the aim of the chiropractor is to locate and correct interferences with this natural expression of the life force. Exclusive focus on this “philosophy” has largely been abandoned by modern evidence-based chiropractors. Other complementary medicine disciplines also have underlying philosophies of life force. It is identified as “chi” in Oriental medicine, “prana” in yoga, “doshas” in Aruvedic medicine, “vix medica naturae” in naturopathic medicine, and each discipline has elaborated some measure of a conceptual life force that guides and propels healing and health.

Conventional medicine with its intellectual traditions anchored in western scientific thought is understandably skeptical of notions of “innate intelligence,” “chi,” or other conceptualization of a putative life force. Finding no “testable hypotheses” to investigate a possible life force, convention has largely dismissed such philosophic musing. Oschman provides a comprehensive review of this seeming “impenetrable intellectual barrier” between CAM and CM world views.

Who uses complementary medicine…and why?

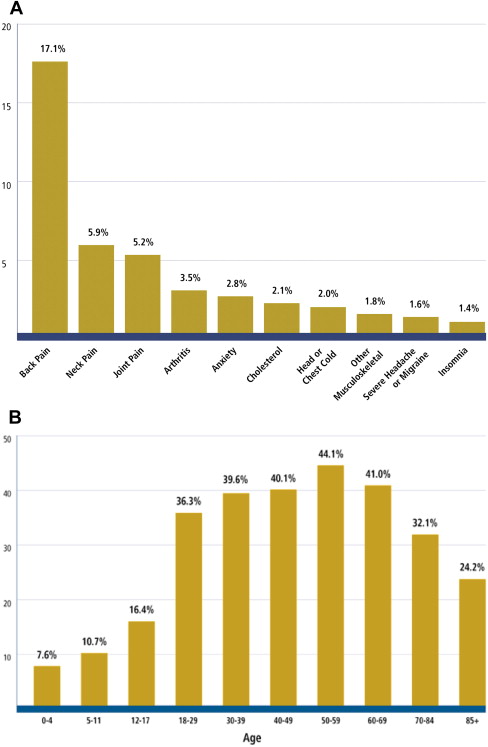

Surveys conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have shown that complementary medicine users come from all demographics. Nearly 40% of the adult population reports using some form of complementary medicine, wherein “complementary medicine” includes both practitioner-based therapies, such as massage and acupuncture, and self-administered treatments, such as deep breathing or nutritional supplements. More than 11% of children have used it as well. Users tend to be more likely female (women generally use more health care services of all types) and have higher levels of education and income. Some studies indicate that complementary medicine appeals to individuals with a heightened sense of self-efficacy and internal locus of control. Complementary medicine use persists into old age. Roughly one-third of adults 70 to 84 years and one-fourth of elders 85 years of age and older use complementary medicine.

Most people use nonmainstream health care along with CM. Dissatisfaction with CM is not usually a motivator for complementary medicine use. Complementary medicine users are likely to report poor health status, that they find symptomatic relief with complementary medicine, and that complementary medicine approaches are consistent with the value they place on the role of nonphysical factors of mind/body connections in health and disease. Users are also more likely to engage actively in their health care decisions rather than “simply to accept unquestionably the physician’s knowledge and expertise.”

Patients use complementary medicine for a wide variety of clinical conditions. Adults most frequently use complementary medicine to treat disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Findings from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey were reported by Barnes and colleagues, as summarized in Fig. 1 .

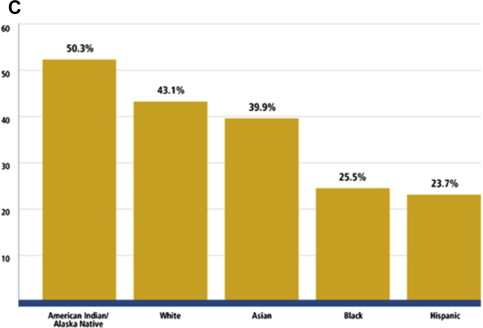

Complementary medicine use by children also is focused on musculoskeletal problems, as shown in Fig. 2 .

Complementary medicine use is common in many clinical populations. A survey of primary care patients at a VA facility found that about one-half of respondents used some form of complementary medicine for managing chronic pain and illness as well as for wellness and health promotion. It is commonly used by patients with cancer along with conventional cancer care. For example, 80% of patients with thyroid cancer, more than 70% of a sample of patients with colon, breast, and prostate cancer, and from 6% to 91% of patients with pediatric cancer report using at least one form of complementary medicine.

Complementary medicine use in chronic pain

As noted in the CDC surveys, complementary medicine is used most commonly for pain problems of the back, neck, joints, arthritis, and other musculoskeletal disorders. Patients with chronic pain report an even higher frequency of complementary medicine use than in the general population.

In a survey of primary care patients on long-term opioid therapy, 44% reported at least one complementary medicine modality over the preceding 12 months. Complementary medicine use has also been reported by more than 40% of patients with peripheral neuropathy, 50% of chronic migraine sufferers, and 52% of primary care patients with chronic pain.

Assessing the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary therapies in chronic pain is problematic. The methodological challenges of efficacy studies in complementary medicine are discussed later. Patient surveys and pragmatic studies of effectiveness of these interventions suggest that most patients using complementary therapies find them helpful.

Chronic Pain

The study by Fleming and colleagues of opioid-using patients with chronic pain in primary care looked at a broad sample of patients with chronic, noncancer pain. Complementary medicine users reported the therapy was “helpful” from 59% (for acupuncture) to 90% (for massage) of the time.

Cancer Pain

CAM use is widespread among patients with cancer. Up to about 60% of adult patients with cancer report using at least one nonconventional treatment for pain, nausea, fatigue, and other cancer-associated symptoms. Forty-four percent of women with lung cancer report CAM use, and 20% of patients at a private cancer clinic report receiving massage. The National Cancer Institute booklet on “Pain Control” notes “other ways to control pain” that include massage, acupuncture, hypnosis, and imagery—biofeedback, meditation, and therapeutic touch (TT). The message to patients with cancer is, “Along with your pain medicine, your health care team may suggest you try other methods to control your pain. However, unlike pain medicine, some of these methods have not been tested in cancer pain studies. But they may help improve your quality of life by helping you with your pain, as well as stress, anxiety, and coping with cancer.”

Headache

An analysis of national health survey data indicated that 50% of US adults with migraines or severe headaches used at least one CAM over the past 12-month period. Self-reported efficacy of complementary medicine approaches, while modest, is prevalent with 40% to 90% of chronic headache patients reporting use of at least one nonconventional therapy.

Low-Back Pain

A Consumer Reports survey of patients intended to provide “real-life accounts” of patient experience with a variety of treatments for low-back pain. Fifty-nine percent of respondents who saw a chiropractor were “completely” or “very” satisfied with their treatment. This report compared with 44% for those who saw a physician specialist and 34% who saw a primary care provider for their back pain. In a “systematic review of systematic reviews” for treatment of nonspecific low-back pain, Kumar and colleagues observed that despite weaknesses in the research designs of the primary studies, “…massage may be an effective treatment option in the short term…”

Surveys of convenience samples of complementary medicine users show 98% of respondents replied “always” or “usually” to the question, “Has the treatment or recommendation you received from this provider helped you?” Eighty-two percent of patients answered “usually” or “always” to: “Has the treatment or recommendation you received reduced your use of prescription drugs?” Ninety-two percent of respondents answered “usually” or “always” to: “Has the treatment or recommendation you received reduced your use of other medical care for this problem?”

Evidence-based complementary medicine

Although patient surveys and pragmatic studies indicate that complementary medicine is helpful, these essentially anecdotal reports are not convincing for many observers. Critics of complementary medicine summarily dismiss it because it is unscientific and lacks a research evidence base. However, a recent search of the Cochrane Collaboration for the term “complementary and alternative medicine” returns 1000 results and 621 reviews. A search of PubMed returns 13,654 citations. A search on PubMed for “acupuncture” returned more than 9000 citations. Limiting the search term to “complementary and alternative medicine and chronic pain” returned 357 citations on PubMed and 107 results on the Cochrane database.

The research on complementary medicine is collated and reviewed in several other databases, as listed in Table 2 . These resources assist researchers as well as clinicians at the bedside. There clearly is a growing body of research on CAM.

| Database | Description | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Standard | Founded by health care providers and researchers to provide high-quality, evidence-based information about CAM including dietary supplements and integrative therapies. Grades reflect the level of available scientific data for or against the use of each therapy for a specific medical condition. | https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/ |

| Natural Medicines Data Base | Has grown to be recognized as the scientific gold standard for evidence-based information on this topic. Leaders in CM as well as complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine recognize the Database as the go-to resource for the most complete and practical information. | http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com/home.aspx?cs=&s=ND |

| Society for Acupuncture Research | Our Mission is to promote, advance, and disseminate scientific inquiry into Oriental medicine systems, which include acupuncture, herbal therapy, and other modalities. We value quantitative and qualitative research addressing clinical efficacy, physiologic mechanisms, patterns of use, and theoretic foundations. | http://www.acupunctureresearch.org/page-1160977 |

| The MANTIS Database | MANTIS addresses all areas of alternative medical literature. It has also become the largest index of peer-reviewed articles for several disciplines, including chiropractic, osteopathy, homeopathy, and manual medicine. | http://www.healthindex.com/MANTIS.aspx |

| Dynamed | Our community of clinicians synthesizes the evidence and provide objective analysis in an easily-digestible format. We follow a strict evidence-based editorial process focused on providing unbiased information to help guide physicians in their decision-making process. | https://dynamed.ebscohost.com/ |

| Trip Database | Trip is a clinical search engine designed to allow users to quickly and easily find and use high-quality research evidence to support their practice and/or care. | http://www.tripdatabase.com/ |

Challenges of evidence-based complementary medicine

Developing the evidence about complementary medicine therapies for chronic pain is problematic from several perspectives. There are problems with blinding of both subjects and clinicians, the confounding caused by expectations that subjects and therapists may bring to interventions involving complementary medicine such as acupuncture, subject allocation by complex clinical conditions that may have multifactorial origins and uncertain clinical end points and, finally, publication and editorial bias.

Complementary medicine therapies are often inherently resistant to analysis by commonly used clinical research methods. For example, in the hierarchy of evidence, the randomized controlled trial (RCT) is considered to be the gold standard. Nevertheless, many argue that this methodology, although well suited to the study of drugs, may not be the best research design to study complex, individualized treatments routinely offered by complementary medicine practitioners. In a drug trial, the mechanism of action is usually well understood, whereas in complementary medicine, the interventions are often multipronged, such as manipulation and exercise in a neck pain trial. Isolating the “active ingredient” in this type of clinical intervention is difficult in the context of an RCT.

Blinding

Trials of manipulative therapy (spinal manipulative therapy [SMT]) and other manual therapies have been plagued by the difficulty in developing a “sham” treatment and concurrently controlling for the “nonspecific” effects of the hands-on practitioner-patient interaction with the sham treatment. Concealing active versus placebo manipulation, for example, is challenging. SMT-naïve research subjects likely can detect genuine from placebo manipulations. SMT-experienced subjects certainly can tell the difference. Blinding the therapist in an SMT trial is similarly quite difficult, especially when compared with blinding of clinicians in a drug trial.

Acupuncture poses similar threats to methodological integrity. Various sham acupuncture interventions have been proposed, including “minimal” needling to only a shallow, putatively nontherapeutic depth, needling at an “inert” acupuncture point, and using a placebo needle that does not penetrate the skin at all. However, these “placebo” procedures produce clinical and physiologic effects that are sometimes indistinguishable from genuine interventions. Acupuncture clinicians discount the existence on inert points, noting the “tree-and-branch” perspective of acupuncture meridians, which suggests that although the flow of chi is maximally affected at traditional acupuncture points, areas adjacent and remote from these points also produce an effect, negating the notion of an “inert” acupuncture point.

Expectations

Expectations by trial participants, patients, and clinicians can further confound the outcomes of all clinical trials. Subjects bring preconceptions, positive or negative, about the trial’s interventions, as revealed in informed consent statements. Subjects biased favorably toward a “complementary medicine” intervention will likely report positive effects, regardless of whether the treatment is active or placebo. Haas and colleagues note in their trial of manipulation that participant expectations and the therapist interaction with the subject “can have a relatively important effect on outcomes in open-label randomized trials of treatment efficacy. Therefore, attempts should be made to balance the DPE [doctor patient encounter] across treatment groups and report degree of success in study publications.”

Allocation

Evidence about any treatment of chronic pain is further confounded by the complex nature of the condition itself. Patient selection is often a significant challenge to study validity. The wide variety of pathologic, functional, and behavioral disorders that are operant in chronic pain conditions defies the development of coherent and consistent diagnostic categories. Combining a wide variety of patients with “low-back pain,” for example, into a conceptually uniform study group ignores the wide variety of conditions that may be classified into this category. It is no wonder that such trials frequently produce equivocal results for almost any intervention whether conventional or complementary and fail to reveal significant differences in effectiveness between treatment arms, between genuine treatment and sham or placebo, or between treatment and no treatment.

End Points

Problems associated with measuring the clinical effect of an intervention in chronic pain conditions are not unique to complementary medicine research. Pain is a subjective experience and has little in the way of an objective clinical finding, such as a laboratory value to evaluate clinical effectiveness. Several instruments are typically used to measure pain before intervention and after intervention, including a variety of pain scales (eg, visual analog pain scales), self-reported disability (Oswestry and neck disability index), and self-reported health (SF-36). Between-subject variability in how these instruments measure pain and changes in pain over time is problematic. Other outcomes, such as return to work or cessation of medical care, have also been suggested. Deyo discusses some approaches to this dilemma in the context of low-back pain research. The development of the PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) by the NIH offers measures of primary and secondary clinical endpoints that are reliable and meaningful to patients.

Publication Bias

Finally, publication and indexing biases are obstacles to assembling and assessing reliable evidence about complementary medicine therapies. As is often the case in CM research, studies with positive results are more likely to be submitted for publication. Many studies of CAM are in foreign language journals, thus limiting their exposure to English-speaking audiences. A more subtle bias also is observed in CM-published research on CAM. As one CAM researcher put it, “A negative study of acupuncture concludes that ‘acupuncture doesn’t work.’ The analogue would be a negative drug trial that concluded ‘medicine does not work” (Hammarschlag R, personal communication, 2005).

The challenges of applying evidence of this nature to the practical realities of treating patients have been increasingly recognized. Fortunately, researchers, particularly in the complementary medicine field, are actively developing research strategies that are more appropriate for both the individualized nature of complementary medicine interventions and the complex, multifactorial nature of chronic conditions, such as chronic pain.

Why should a physiatrist learn about complementary and alternative medicine therapies for chronic pain?

There is a compelling case why CM physicians, especially in the challenging field of pain medicine, might want to better understand complementary medicine therapies.

- •

Because complementary medicine use is widespread, it is more likely than not that patients with chronic pain are already using at least one CAM therapy concurrently with conventional treatments.

- •

The evidence for some complementary therapies is equivalent to that which supports many commonly prescribed conventional treatments ( Table 3 ).

Table 3

Comparison of the evidence for conventional and complementary therapies for low-back pain

Therapy

Evidence as Summarized by Cochrane Collaboration Reviews

NSAIDs

The review authors conclude that NSAIDs are slightly effective for short-term symptomatic relief in patients with acute and chronic low-back pain without sciatica (pain and tingling radiating down the leg). In patients with acute sciatica, no difference in effect between NSAIDs and placebo was found. Only 42% of the studies were considered to be of high quality.

Opioids

In general, people that received opioids reported more pain relief and had less difficulty performing their daily activities in the short term than those who received a placebo. However, there are little data about the benefits of opioids based on objective measures of physical functioning. We have no information from RCTs supporting the efficacy and safety of opioids used for more than 4 mo. Furthermore, the current literature does not support that opioids are more effective than other groups of analgesics for low-back pain, such as anti-inflammatories or antidepressants. The quality of evidence in this review ranged between “very low” and “moderate.” See more at: http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD004959/BACK_opioids-for-the-treatment-of-chronic-low-back-pain#sthash.axeqopHv.dpuf

Therapeutic ultrasound

We did not find any convincing evidence that ultrasound is an effective treatment of low-back pain. There was no high-quality evidence that ultrasound improves pain or quality of life. The quality of the evidence on ultrasound leaves much to be desired. In this review, we found “moderate” quality evidence regarding back-related function. The evidence on other outcomes was of “low” or “very-low” quality.

SMT

The results of this review demonstrate that SMT appears to be as effective as other common therapies prescribed for chronic low-back pain, such as exercise therapy, standard medical care, or physiotherapy.

Acupuncture

For chronic low-back pain, results show that acupuncture is more effective for pain relief than no treatment or sham treatment, in measurements taken up to 3 mo. The results also show that for chronic low-back pain, acupuncture is more effective for improving function than no treatment, in the short term. Acupuncture is not more effective than other conventional and “alternative” treatments. When acupuncture is added to other conventional therapies, it relieves pain and improves function better than the conventional therapies alone.

Massage therapy

Massage was more likely to work when combined with exercises (usually stretching) and education. The amount of benefit was more than that achieved by joint mobilization, relaxation, physical therapy, self-care education, or acupuncture. It seems that acupressure or pressure point massage techniques provide more relief than classic (Swedish) massage, although more research is needed to confirm this. In summary, massage might be beneficial for patients with subacute (lasting 4 to 12 wk) and chronic (lasting longer than 12 wk) nonspecific low-back pain, especially when combined with exercises and education.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree