Abstract

A diagnosis of esophageal perforation at some time after cervical spine surgery is difficult to establish since there exists no clinical picture specific to tetraplegic patients. We carried out a detailed retrospective study of revelatory clinical manifestations and conventional radiographic data in a series of 16 patients hospitalized at Hôpital Henry-Gabrielle (Lyon, France) for rehabilitation purposes between 1983 and 2010 and who presented this complication. The most frequent clinical picture associates cervical pain, fever and dysphagia. Simple front and side X-rays of the cervical spine led in 77% of the cases to a diagnosis of esophageal perforation. The most prevalent radiographic signs of the latter consist in osteosynthesis hardware or instrumentation failure, prevertebral free air next to the cervical esophagus and enlarged prevertebral space. Visualized esophageal X-rays, also known as series, highlight parenchymal opacity next to the posterior wall of the esophagus. A diagnosis of esophageal perforation needs to be carried out in order to facilitate suitable treatment and avoid the compromising of vital functions.

Résumé

Le diagnostic de perforation œsophagienne à distance de la chirurgie cervicale est difficile à poser devant l’absence de tableau clinique spécifique dans la population de tétraplégiques. Nous avons réalisé une étude rétrospective détaillée des manifestations cliniques révélatrices et des données de la radiologie conventionnelle chez une série de 16 patients hospitalisés à l’hôpital Henry-Gabrielle pour rééducation entre 1983 et 2010 ayant présenté cette complication. Le tableau clinique le plus fréquent associe douleur cervicale, fièvre et dysphagie. Les radiographies simples du rachis cervical face et profil ont permis de suspecter le diagnostic de perforation œsophagienne dans 77 % des cas. Les signes radiographiques les plus fréquents sont une défaillance du montage du matériel d’ostéosynthèse, la présence de clartés aériques prévertébrales en regard de l’œsophage cervical et un élargissement de l’espace prévertébral. Le transit œsophagien permet de mettre en évidence une image d’addition en regard de la paroi postérieure de l’œsophage. Le diagnostic de perforation de l’œsophage est important à poser pour permettre un traitement adapté et éviter une mise en jeu du pronostic vital.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The annual incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury is estimated at 19.4 new cases a year by one million inhabitants in France, including 500 cases of cervical spinal cord injuries a year . Treatment of cervical spine trauma is more often than not surgical, and it is aimed at achieving medullary decompression, fracture reduction and a stabilized cervical spine. The anterior approach of the cervical spine is presently the most widely used. It permits ablation of the bone and disc fragments likely to compress the dural sheath forwards, and the approach also facilitates diagnosis of a dural breach. Fracture reduction is completed by osteosynthesis with installation of a generally autologous bone graft accompanying the fixation hardware .

Esophageal perforation is a rarely encountered complication of anterior cervical surgery, and its incidence is lower than 1.5% . The main revelatory clinical manifestations identified in a series of 44 cases following anterior cervical surgery include fever, sore throat, neck pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, alteration of the voice and cervical induration. There also exist forms that are paucisymptomatic , asymptomatic or associated with different complications (fistula, cellulitis, mediastinitis) that explain a delay in diagnosis . A perforation diagnosis is confirmed by tomodensitometry (TDM) tests and magnetic resonance imagery (MRI) of the cervical spine as well as endoscopic exploration . According to a preliminary study carried out in four tetraplegia patients presenting with an esophageal fistula , conventional radiography may prompt suspicion of a fistula diagnosis by underscoring indirect signs such as prevertebral free air behind the esophagus, an osteosynthesis device anomaly or enlargement of prevertebral space.

The objective of this work is to provide a detailed retrospective analysis of the revelatory clinical manifestations as well as conventional radiological data in a series of 16 patients presenting with post-traumatic tetraplegia complicated by an esophageal perforation.

1.2

Method

1.2.1

The population studied

Sixteen patients presenting with tetraplegia secondary to fracture of the cervical spine, operated through an anterior approach and complicated by an esophageal perforation, were included in the study. Between 1983 and 2010, these patients had been hospitalized in Hôpital Henry-Gabrielle (Lyon, France) for the purposes of rehabilitation. The esophageal perforation diagnosis had been confirmed in every one of these cases by endoscopic or intraoperative radiological explorations (esophageal series, TDM, MRI).

1.2.2

Method

This was a retrospective study. For each patient, data consisted in: age, sex, characteristics of the cervical spine trauma (cause, type of cervical lesion, presence of intracanal fragments or of a dural breech noted during the preoperative examination), type of surgical treatment carried out (corpectomy, discectomy, nature of the graft, the osteosynthesis instrumentation employed), presence of associated thoracic trauma, tetraplegia characteristics (ASIA and Frankel sensory and motor scores, last healthy neurological level), intubation duration and presence of a tracheotomy ( Table 1 ).

| Patients | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of accident | 1983 | 1984 | 1986 | 1986 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1999 | 2003 | 2003 | 2003 | 2004 | 2004 | 2006 | 2010 |

| Sex (M/F) | M | M | F | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | M |

| Age (years) | 30 | 26 | 44 | 30 | 18 | 18 | 41 | 20 | 22 | 28 | 18 | 47 | 41 | 20 | 27 | 24 |

| Neurological motor level | C4 | C6 | C7 | C5 | C7 | C7 | C6 | C8 | C8 | C6 | C5 | C8 | C6 | C7 | C5 | C5 |

| ASIA motor score (/100) | 2 | 20 | 19 | 14 | 40 | 14 | 25 | 16 | 19 | 12 | 4 | 25 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 22 |

| ASIA sensory score (/224) | 24 | 40 | 84 | 32 | 224 | 166 | 68 | 208 | 62 | 176 | 117 | 34 | 64 | 20 | 32 | 82 |

| Frankel score (A to E) | A | A | B | A | B | B | C | C | A | B | B | A | A | A | A | A |

| Type of cervical lesion (lux: dislocation) | Fr Lux C5C6 | Lux C5C6 | Lux C5C6 | Fr Lux C5C6 | Fr C7 | Fr Lux C5C6 | Fr Lux C5C6 | Fr C5 | Fr Lux C6C7 | Fr Lux C5C6 | Fr Lux C4C5 | Fr Lux C6C7 | Fr Lux C6C7 | Fr Lux C5C6; Fr C7 | Fr Lux C5C6 | Fr C6 |

| Bone fragments Intracanal (P) | – | – | – | P | P | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | P | P | – | – |

| Dural breech (P) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | P | – | P | – | – |

| Associated thoracic trauma (P) | – | P | – | – | – | – | – | P | – | P | – | – | P | P | P | – |

| Delay between accident and surgery (days) | 2 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Graft (A or H) | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | H | A | H | A |

| Corpectomy/Discectomy | C | D | D | D | C, D | D | C, D | D | D | C, D | C | C | D | C, D | C, D | C |

| Intubation duration (days) | 9 | 27 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 24 | 70 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 13 |

| Tracheotomy (P) | P | – | – | P | – | – | – | – | – | – | P | – | P | – | – | P |

| Diagnosis | FOPB | PO | FOC | FOT | PO | PO | PO | PO | FOC | PO | FOT | PO | FOT | PO | PO | PO |

| Delay between surgery and diagnosis (days) | 1005 | 21 | 478 | 63 | 1391 | 59 | 95 | 94 | 9 | 116 | 31 | 28 | 79 | 39 | 317 | 97 |

Two types of parameters were studied:

- •

clinical manifestations revealing the perforation: cervical pain, dysphagia, pain when swallowing, fever, anterior cervical tumefaction, cervical outflow, meningitis, swallowing the wrong way, repeated respiratory events (bronchial congestion, pneumopathy, pleurisy);

- •

anomalies or abnormalities underscored by front and side X-rays of the cervical spine in a seated position: osteosynthesis hardware failure (shift in position of an osteosynthesis plate, shift in position or migration of a screw, presence of a screw in the interdiscal space or in the graft), prevertebral free air next to the cervical esophagus, enlarged prevertebral space, anomalous bone alignment and bone lysis, parenchymal opacity on the visualized esophageal X-rays using the contrast medium known as gastrografin.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Characteristics of the population studied

Patient characteristics are presented hereinafter ( Table 1 ). The population studied comprised 16 patients with a mean age of 28.38 years. The cervical spine trauma resulted in 13 cases from a traffic accident, in two cases from falling off a tree and in one case from a diving accident. All of the patients presented with sensory and motor tetraplegia. None of them presented with motor functions below the level of injury.

Eighty-one percent of the patients presented with cervical dislocation. All of the patients had undergone surgical treatment using anterior cervical approach with osteosynthesis associating the installation of a graft and the fixation of hardware. The average lapse of time between the date of the accident and the operation was 2 days. Mean duration of intubation was 11.94 days. Four out of the 16 patients presented a surgical complication necessitating a second operation; in two cases fracture reduction was incomplete, in two cases the osteosynthesis instrumentation had shifted in position, and in one case the complication was of an infectious nature.

The esophageal perforation was isolated in 10 cases, associated with a tracheal fistula in three cases, cutaneous in two cases and pleurabronchial in one case. The perforation diagnosis was confirmed in all cases by endoscopic and/or radiological explorations (fistulography, esophageal series with gastrografin, TDM, MRI) and in three cases by intraoperative examination. The mean time lapse between cervical surgery and perforation diagnosis was 8 months, and it ranged from 9 days to 3.8 years.

Treatment of the esophageal perforation was surgical in 12 cases, associated with the ablation of osteosynthesis hardware in nine cases, and it was medical in three cases with cessation of oral feeding and systemic antibiotic treatment. One patient died before treatment got underway.

1.3.2

Clinical symptoms

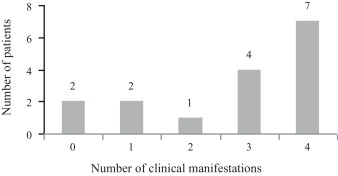

Table 2 presents the different clinical manifestations revealing an esophageal fistula. The most frequently encountered symptoms are fever, cervical pains and dysphagia. Eleven patients presented with three or more associated clinical signs ( Fig. 1 ). Two patients were asymptomatic (cases 4 and 7).

| Number of patients out of 16 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | 9 | 56 |

| Cervical pain | 8 | 50 |

| Dysphagia | 8 | 50 |

| Pain when swallowing | 6 | 38 |

| Repetitive respiratory events (congestion, pneumopathy and/or pleurisy) | 5 | 31 |

| Anterior cervical tumefaction | 4 | 25 |

| Cervical abscess outflow | 2 | 13 |

| Food “down the wrong pipe” | 1 | 6 |

| Postoperative meningitis | 1 | 6 |

1.3.3

Radiological signs

Simple front and side X-rays of the cervical spine were carried out in 13 of the 16 patients. Table 3 presents the different abnormalities that were displayed.

| Number of patients out of 13 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Osteosynthesis hardware failure | 10 | 77 |

| Prevertebral free air next to the cervical esophagus ophage | 8 | 62 |

| Enlarged prevertebral space | 6 | 46 |

| Anterior vertebral wall no longer aligned | 4 | 31 |

| Presence of a screw on abdominal radiography without preparation | 2 | 15 |

| Bone lysis | 2 | 15 |

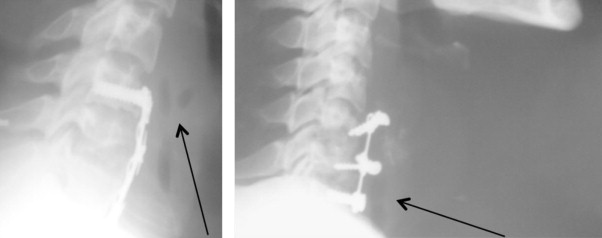

The most frequently encountered anomalies or abnormalities were osteosynthesis hardware failure, prevertebral free air next to the cervical esophagus and enlarged prevertebral space ( Fig. 2 ).

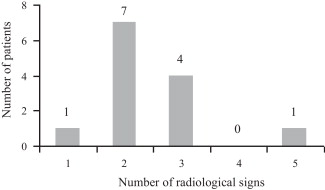

Cervical spine X-rays were abnormal in all of the 13 patients, and in 12 cases, they showed more than two anomalies ( Fig. 3 ). The two most pertinent radiological abnormalities with regard to suspected esophageal perforation were those showing prevertebral free air and the presence of a screw on abdominal radiography without preparation (77% of the cases).

Ten patients were observed in esophageal images taken in series with gastrografin. Parenchymal opacity favoring a perforation diagnosis was shown to exist in seven patients (70%), along with a fistular trajectory in five patients.

1.4

Discussion

The objective of this study was to retrospectively analyze the clinical symptoms and the radiographic abnormalities revealing an esophageal perforation in 16 patients presenting with tetraplegia secondary to cervical trauma.

The results show that the most frequently encountered revelatory clinical manifestations are fever, dysphagia and cervical pain. These results are comparable to those found in previous series . None of the symptoms are specific to esophageal perforation. Pain and dysphagia are frequent symptoms after anterior cervical surgery, with their prevalence lessening in time . In a similar way, repetitive bronchial episodes constitute a frequent complication on tetraplegic patients . A combination of several symptoms appears to strongly suggest an esophageal perforation but may be explained by difficulties in arriving at a diagnosis.

The results also show that all the patients presented abnormalities on the simple X-rays of the cervical spine. As is the case with the clinical symptoms, the simultaneous existence of several abnormalities should lead to suspicion of an esophageal perforation. The most widespread abnormality involves the osteosynthesis hardware. The other abnormalities (prevertebral free air and enlarged prevertebral space) are more difficult to identify and necessitate an experienced eye. They nonetheless strongly suggest an esophageal perforation .

The prevertebral free air may correspond to the passage of esophageal air by the perforation or to an infection with anaerobic germs.

As for the enlarged prevertebral space, it attests to abnormal collection in front of the cervical fracture.

These results highlight the interest of systematically performing front and side X-rays of the cervical spine in post-traumatic tetraplegic patients having undergone anterior operation, and these examinations should be renewed during disease evolution in the event of a suggestive clinical symptom. Moreover, the abnormalities present in the simple spinal X-rays remain visible at a complicated stage of esophageal perforation .

Esophageal series confirmed the diagnosis of seven patients out of 10 (70%). The results of the radiographic examinations are often difficult to read because the osteosynthesis hardware creates artifacts.

According to Gaudinez et al., in 22.7 of the reported cases, tomodensitometric and magnetic resonance examinations do not justify affirmation of the diagnosis .

In 50 to 63.6% of the reported cases, endoscopic pharyngo-esophageal exploration confirms the presence of an esophageal lesion .

In a review dating back to 2007, the authors recommend X-rays and first-line esophageal series when perforation of the esophagus is suspected .

The physiopathological mechanisms of esophageal perforation appear to be multiple. The initial trauma may indirectly occasion an esophageal lesion through injury of the posterior esophageal wall by means of a bone fragment or through shearing of the wall during hyperextension trauma .

The esophageal wall may have been damaged during the operation. Some authors have suggested that a lesion was due to blunt surgical devices or to ischemic compression occasioned by the retractors used during the operation . In our series, there exists a lengthy delay, averaging eight and a half months, between cervical surgery and the perforation diagnosis. Late discovery of the presence of an esophageal perforation has previously been mentioned in the literature , and the sizable time lapse does not favor the hypothesis of a direct intraoperative lesion.

The wall of the esophagus may have been damaged during intubation . In our series, the patients presenting with a fistula between the esophagus and the respiratory tract were all equipped with a tracheotomy. The esophageal wall may likewise have been damaged while the tracheotomy was being performed or favored by use of a tracheotomy tube (shearing injury, inflammation of the tracheal wall). In addition, a respiratory tract fistula may occasion a tracheotomy procedure on account of the extubation difficulties associated with the repeated occurrence of respiratory infections. Moreover, 77% of the patients in our study showed an anomaly in the positioning of the osteosynthesis hardware, and several authors have suggested that osteosynthesis devices may indeed have a traumatizing effect on the esophageal wall. The literature reports less elevated ratios (2.33 to 35%) of hardware device failure following anterior cervical osteosynthesis . In our series, shift in position of the osteosynthesis hardware would appear to be a risk factor with regard to perforation of the posterior pharyngo-esophageal wall, and it may be at the origin of repetitive micro-traumas on the posterior wall of the esophagus. Hanci et al. have suggested that osteosynthesis hardware may exert pressure on that wall; this factor, as well, may help to explain the delay in discovery of esophageal perforations .

In a series of 109 patients monitored for 2 years after a degenerative cervical lesion led to anterior approach surgery , a new operation subsequent to osteosynthesis hardware failure showed a form of tissue realignment in the vicinity of the hardware that was highly unlikely to injure adjacent structures. Not a single patient presented with an esophageal lesion. According to Sahjpaul et al., the existence of paucisymptomatic forms and an unexpectedly low mortality rate may be explained by the slowness of esophageal screw migration in an overall context of circumscribed inflammation .

Given the absence of a clinical picture specific to tetraplegic patients, a diagnosis of esophageal perforation at some time after cervical surgery is particularly difficult to obtain. In our series of 16 patients, the most frequent clinical picture associated fever, cervical pain and dysphagia. Simple front and side X-rays of the cervical spine led in 77% of the cases to a suspected esophageal perforation diagnosis. The most commonly noted radiographic signs were osteosynthesis hardware or instrumentation failure, the presence of prevertebral free air next to the cervical esophagus and enlarged prevertebral space. Visualized esophageal X-rays highlighted parenchymal opacity next to the posterior wall of the esophagus. A diagnosis of esophageal perforation needs to be carried out in order to facilitate suitable treatment and avoid the compromising of vital functions. Evolution is long-term, and numerous setbacks and relapses are to be expected .

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’incidence annuelle des lésions médullaires d’origine traumatique est estimée à 19,4 nouveaux cas par an par millions d’habitants en France dont 500 cas de lésions de la moelle cervicale par an . Le traitement du rachis cervical traumatique est le plus souvent chirurgical avec pour objectifs la décompression médullaire, la réduction de la fracture et la stabilisation du rachis cervical. L’abord antérieur du rachis cervical est actuellement le plus utilisé. Il permet l’ablation de fragments osseux et discaux susceptibles de comprimer le fourreau dural en avant et le diagnostic d’une brèche durale. La réduction de la fracture est complétée par une ostéosynthèse avec pose d’un greffon osseux, le plus souvent autologue, associée à du matériel de fixation .

La perforation de l’œsophage est une complication rare de la chirurgie cervicale par voie antérieure, dont l’incidence est inférieure à 1,5 % . Les principales manifestations cliniques révélatrices sont la fièvre, le mal de gorge, les douleurs cervicales, la dysphagie, l’odynophagie, la modification de la voix et l’induration cervicale identifiées dans une série de 44 cas après chirurgie cervicale antérieure . Il existe également des formes paucisymptomatiques , asymptomatiques ou associées à des complications (fistule, cellulite, médiastinite) à l’origine d’un retard de diagnostic . Le diagnostic de perforation est confirmé par les examens tomodensitométriques (TDM), d’imagerie par résonnance magnétique (IRM) du rachis cervical ainsi que l’exploration endoscopique . D’après une étude préliminaire réalisée chez quatre patients tétraplégiques présentant une fistule œsophagienne , la radiographie conventionnelle peut faire suspecter le diagnostic de fistule en mettant en évidence des signes indirects tels que des clartés aériques prévertébrales en arrière de l’œsophage, une anomalie du matériel d’ostéosynthèse ou un élargissement de l’espace prévertébral.

L’objectif de ce travail est une analyse rétrospective détaillée des manifestations cliniques révélatrices et des données de la radiologie conventionnelle chez une série de 16 patients présentant une tétraplégie post-traumatique compliquée d’une perforation œsophagienne.

2.2

Méthode

2.2.1

Population étudiée

Seize patients présentant une tétraplégie secondaire à une fracture du rachis cervical opérée par voie antérieure et compliquée d’une perforation œsophagienne sont inclus dans l’étude. Ces patients ont été hospitalisés à l’hôpital Henry-Gabrielle pour rééducation entre 1983 et 2010. Le diagnostic de perforation de l’œsophage a été confirmé dans tous les cas par des explorations radiologiques (transit œsophagien, TDM, IRM), endoscopiques ou peropératoires.

2.2.2

Méthode

Il s’agit d’une étude rétrospective. Pour chaque patient, les données recueillies sont : l’âge, le sexe, les caractéristiques du traumatisme du rachis cervical (cause, type de lésion cervicale, présence de fragments intracanalaires ou d’une brèche durale notés à l’examen peropératoire), le traitement chirurgical réalisé (corporectomie, discectomie, nature de greffon, matériel d’ostéosynthèse), la présence d’un traumatisme thoracique associé, les caractéristiques de la tétraplégie (scores moteur et sensitif ASIA et Frankel, dernier niveau neurologique sain), la durée de l’intubation et la présence d’une trachéotomie ( Tableau 1 ).