Clinical Diagnosis and Imaging

Gregory Gramstad

Guido Marra

INTRODUCTION

History and clinical evaluation are the cornerstones by which patients with elbow complaints are managed. These steps are important because they allow the treating physician to evaluate a patient’s subjective and objective level of disability. Only after these steps are completed does an accurate reflection of the patients’ state of health exist. Correlating this information with patients’ expectations allow the treating physician to properly outline appropriate treatment options.

In this chapter pertinent pathologic conditions of the elbow are reviewed. A systematic approach to elbow examination is presented. A systematic approach for evaluation of common pathologic elbow conditions is provided.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FOR CONDITIONS REQUIRING ARTHROPLASTY

Osteoarthritis

Primary osteoarthritis (OA) of the elbow is a rare condition that presents most frequently in the dominant extremity of middle-aged working males. Disability is primarily caused by limitation of elbow flexion and pain at the extremes of motion. Care should be made to rule out inflammatory causes of joint degeneration and to look for secondary causes for OA that affect treatment and outcomes.

OA is the most common articular disease, affecting millions of people worldwide. Attention to this common condition has been more focused over the last several decades because it has been recognized as a major source of disability and health care expenditure. With the advent of arthroscopy and other treatment options, a sustained interest in the treatment of this condition has emerged.

Pathogenesis

Primary OA is a disease that originates in hyaline articular cartilage, causing its progressive destruction and alteration of the subchondral bone. Articular geometry is slowly altered through cartilage remodeling, capsular and synovial thickening, marginal osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis, and subchondral cyst formation.

The role of systemic and local biomechanical and biochemical alterations is under investigation. Genetics, aging, bone density, muscle weakness, joint laxity, and obesity have all been cited as possible etiologic factors in the development of OA (1,2). Although aging and repetitive microtrauma have been shown to alter articular cartilage, normal lifelong joint use has not been shown to cause degeneration (2). Changes in osteoarthritic cartilage do not parallel the changes in the cartilage of a normal aging adult, implying genetic and molecular etiologies. An underlying imbalance in the cytokine-mediated anabolic and catabolic processes of articular cartilage regeneration appears to have some role (3).

Mechanical factors also play an important role in the pathogenesis of cartilage destruction. The interstitial water supports approximately 95% of a compressive load in normal cartilage (2). In osteoarthritic cartilage, water content and permeability increase as the hydrophilic proteoglycan content decreases. The hydraulic strength proportionately decreases, subjecting the collagen matrix to a greater proportion of the applied loads. Compressive joint reaction forces across the elbow have been shown to reach six times body weight during throwing or heavy pounding, which belies the assumption that the elbow is not a weightbearing joint (4).

Alterations in joint biomechanics can cause an increase in the joint reaction force. Chronic strain from heavy repetitive motion has been shown to cause laxity of the elbow’s stabilizing collateral ligaments (5). Cartilage injury from repetitive microtrauma can cause a localized thickening of the subchondral bone at the expense of uncalcified hyaline cartilage thickness (2). Cartilage thinning leads to an altered ability to resist normal shear forces and compressive loading, accelerating joint degeneration in the effected compartment.

A disparity exists between the wear patterns of normal aging elbows and those requiring surgical intervention. Goodfellow and Bullough provide a description of the pattern of wear in 28 cadaver elbows of varying age (6). They report a consistent and progressive erosion of the radiocapitellar joint in all specimens with a relative sparing of the ulnohumeral articulation. In contrast, Morrey found that of 15 elbows undergoing surgical treatment, all displayed significant ulnohumeral disease, whereas radial head osteophytes were present in only seven (7). One hypothesis for this disparity would state that attenuation of the medial collateral ligament, from repetitive stress, or an altered joint line, from pediatric fracture, caused a chronic alteration in medial joint reaction force. The ulnohumeral joint must then increase its contribution to joint stability at the expense of altered loading patterns. This situation is analogous to the valgus extension overload seen in the pitching elbow with posteromedial ulnohumeral impingement and posterior osteophyte formation (8). Edge loading and olecranon impingement decrease the weightbearing surface of the articulation, causing an uneven distribution of compressive stresses (9). Damage to the cartilage and hypertrophy of the subchondral bone accelerate the progression to OA by the aforementioned mechanisms.

Two studies have reported the incidence of primary symptomatic OA in the elbow joint to be approximately 2% to 8% (10, 11, 12). Stanley reported on the prevalence of primary elbow OA in 1,000 consecutive patients attending a fracture clinic. All cases of previous periarticular elbow fracture, multiple joint OA, and posttraumatic arthritis were excluded. It was discovered that more than 10% of those involved with heavy labor had primary OA of the elbow and none were younger than 40 years of age. A report by Doherty and Preston emphasized the high association between elbow and metacarpophalangeal involvement in the axial digits (62%), which may strengthen the association to the repetitive microtrauma hypothesis (13).

Clinical Significance

Patients with primary OA frequently present with activityrelated joint pain and restriction of motion. A definable periarticular or ligamentous injury may be recalled, but most have no recollection of prior injury. Middle-aged males are many times more likely to be afflicted than females, with the dominant extremity involved in 54% to 90% of cases (10,13, 14, 15, 16). Approximately 60% to 80% report an occupation or proclivity for an activity that involves a heavy repetitive use of the dominant arm (10,15). Individuals who use the upper extremities for prolonged crutch ambulation or wheelchair mobility have been diagnosed with OA in the elbow as well (7).

Clinical Evaluation

History

The mechanical impingement pain of OA typically occurs at the extremes of motion. Classically, painful terminal extension is noted in daily life when lifting heavy objects or carrying items with the elbow extended. Its severity is quite variable and does not reliably relate to the stage of disease. The patient’s current activity and occupational demands will largely dictate how disabling the arthritic process has become, regardless of radiographic staging. Typically, there is a modest flexion contracture with an average arc of motion from 30 to120 degrees. Approximately 50% will have pain with attempted full

flexion (7). Pain throughout the arc of motion is indicative of advanced disease. Forearm rotation usually is not affected.

flexion (7). Pain throughout the arc of motion is indicative of advanced disease. Forearm rotation usually is not affected.

Physical Examination

A primary goal in the evaluation of a patient with OA is to rule out inflammatory conditions and identify possible causes of secondary OA that could respond to medical therapy. In highly active young laborers, sources of referred pain from the neck should be sought if the pain is severe and unchanged throughout the range of motion. A careful neurologic examination can reveal a concomitant radiculopathy or neuropathy from cervical stenosis or peripheral entrapment. Examination of the ulnar nerve is essential because 10% to 30% of patients will show signs of neuritis from excessive ulnohumeral osteophyte formation (14,16). Radial nerve entrapment at the arcade of Frohse can cause a lateral elbow pain syndrome, which may mimic some symptoms of OA (17). Aspiration is used to rule out crystalline deposition disease, which could respond to medical therapy, or infection requiring debridement.

Radiographic Imaging

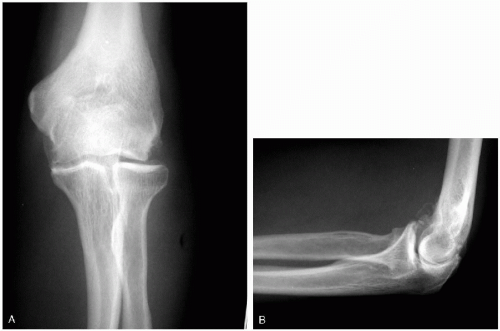

Radiographic evaluation assists in staging and can elucidate other important features of the arthritic condition. The lateral view typically reveals osteophytes on the olecranon and coronoid processes. The anteroposterior view shows ossification and osteophytes filling the olecranon fossa (15,18) (Fig. 23-1). Radiocapitellar involvement occurs in the later stages of disease. Loose bodies are found in approximately 50% of degenerative elbows (7). Their presence is a radiographic feature of primary OA that can cause pain and locking (19). Large chondral lesions of the capitellum can occur in younger individuals and represent one potential cause of secondary OA. A significant number of these individuals will present with degenerative change in the elbow joint at an early age (20).

Posttraumatic Arthritis

Elbows with significant deformity, instability, and/or bone loss have few options for reconstruction. Previous surgeries with attenuated soft tissues, avascular bone, retained hardware, and scarring of the ulnar nerve further complicate the treatment. The success of total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) lies in careful patient selection and an active preoperative evaluation of risk factors for failure.

Arthritis is an end-stage complication of traumatic conditions with residual articular or periarticular deformity, instability, and bone loss. The general consensus is that

anatomic restoration after trauma is the surest way to avoid this dreaded complication. Unfortunately, despite the most careful efforts to restore anatomic alignment, articular congruence, motion, and stability to the elbow, malunion, nonunion, and/or arthritis may result.

anatomic restoration after trauma is the surest way to avoid this dreaded complication. Unfortunately, despite the most careful efforts to restore anatomic alignment, articular congruence, motion, and stability to the elbow, malunion, nonunion, and/or arthritis may result.

Pathogenesis

Malunited intraarticular fractures of the distal humerus, radial head, and olecranon can result in posttraumatic arthritis. When open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are required, anatomic restoration of the injured articular surface is the primary goal. Residual articular incongruity can result in accelerated cartilage wear at a rate dependent on the residual malalignment and the demand placed on the elbow. Osteochondral or chondral defects can thwart even the best articular reductions and result in accelerated wear of the opposing articular surface. Periarticular deformity, particularly in the coronal plane, can result in accelerated joint wear by altering the forces across the elbow.

Residual elbow instability following traumatic injury can also lead to progressive cartilage wear and joint space narrowing. The elbow joint is highly constrained and does not tolerate alterations in stability without consequence. Minor alterations in ulnohumeral biomechanics secondary to ligamentous attenuation can lead to accelerated ulnohumeral degeneration.

Clinical Significance

Posttraumatic arthritis is particularly troublesome because it often affects a younger active patient population. Many years of heavy use are to be expected, and early advanced arthritis can adversely affect a patient’s ability to resume a previous occupation, often with significant social consequences. Unfavorable outcomes after reconstruction are often associated with multiple surgeries, infectious complications, instability, deformity, and bone loss (4,21, 22, 23, 24, 25).

Clinical Evaluation

History

Subjective complaints include pain, loss of motion, instability, weakness, and/or paresthesias. A determination of arm dominance, functional demands, previous surgeries, infectious complications, and subjective disability are important. A complete history includes a detailed account of the original injury and subsequent treatment. One study of 41 patients treated with TEA for posttraumatic arthritis found only three patients had not undergone prior procedures (21). Patients younger than 60 years of age averaged 2.7 procedures.

Providing patients with realistic expectations is important so that they understand how the available treatment options can best fit their needs. The expectations of an elderly sedentary patient will differ from the demands of a young laborer. Clear communication between patient and physician is required to optimize the end result of treatment.

Physical Examination

Physical examination must include an assessment of previous incisions, signs of infection, and limb alignment. Multiple previous procedures can leave the cutaneous soft-tissue envelope susceptible to devascularization, necessitating flap reconstruction if careless dissection is undertaken. Prominent hardware can cause irritation and skin breakdown around the elbow. Abundant granulation tissue should raise the suspicion of previous infection.

Evaluating the carrying angle of the elbow, as compared to the contralateral limb, a deformity of the limb can be present. Schneeberger and Morrey noted that patients with significant preoperative deformity had a higher rate of mechanical failure after TEA (50%) than individuals without marked deformity (6%) (21). The severity of arthritis and need for capsular release can be determined by testing range of motion.

A complete evaluation of all the neurovascular structures of the limb must be obtained. Morrey and colleagues found that there was a 20% incidence of ulnar neuropathy and 5% incidence of partial radial nerve neuropathy in patients with posttraumatic arthritis of the elbow at presentation (22). Ulnar nerve impingement or tethering can be caused by hypertrophic osteophytes or periarticular fibrosis in and around the cubital tunnel (26). A history of dislocation should prompt careful examination of both ulnar and median nerves.

Stability testing should assess the integrity of the collateral ligaments and elicit subtle posterolateral rotary instability. Instability is a frequent finding, occurring in 61% of patients requiring TEA for posttraumatic arthritis (21). Frank subluxation or dislocation was noted on preoperative radiographs in 17 of those 41 patients. The pattern and severity of instability can directly affect the constraint required if TEA becomes necessary.

Radiographic Imaging

Standard radiographs of the elbow can delineate the severity of arthritis, the presence of malunion or nonunion, the nature of implanted hardware, and the extent of associated bone loss. Significant bone loss, representing the loss of one or both humeral condyles, will be seen in one-third to one-half of patients (21,22). Clues to the nature of previous reconstructive procedures can be obtained, and the quality of the bone can be noted.

Ancillary Studies

Laboratory assessment of infection, including aspiration, is warranted in any patient with a history of prior surgery or infection. Reported deep infection rates after TEA in

patients with a diagnosis of posttraumatic arthritis range from 5% to 20%; the majority occur in patients with a concomitant history of previous surgery (27, 28, 29). One study reported a 33% incidence of post-TEA infection in patients with a prior history of infection (28). Previous flap reconstruction or arterial injury should prompt arteriography, and nerve conduction studies should be obtained as the clinical examination dictates (23).

patients with a diagnosis of posttraumatic arthritis range from 5% to 20%; the majority occur in patients with a concomitant history of previous surgery (27, 28, 29). One study reported a 33% incidence of post-TEA infection in patients with a prior history of infection (28). Previous flap reconstruction or arterial injury should prompt arteriography, and nerve conduction studies should be obtained as the clinical examination dictates (23).

Synovial-Based Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis remains the most common indication for TEA. Patients with inflammatory arthropathies often have general medical conditions that require optimization prior to any surgical intervention. Improved results with semi-constrained TEA in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) approach the results of lowerextremity arthroplasty.

Patients with inflammatory arthropathies comprise the single largest cohort requiring TEA. Nearly two-thirds of patients with RA will suffer from degenerative disease of the elbow (30,31). The first surgical experience with total elbow replacement was limited to those afflicted with RA (32). Elbow degeneration has been observed in other inflammatory arthropathies, including juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), crystalline arthritis, hemophilia, and reactive or postinfectious arthritis (ulcerative colitis, Reiter’s disease, rheumatic fever) (25,29,33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38). Although aggressive rheumatoid disease presents a complex challenge to reconstruction, the results of elbow arthroplasty are similar to the long-term success seen in the hip and knee arthroplasty (39).

Pathogenesis

The primary lesion in rheumatoid disease is an invasive inflamed synovium. The exact pathogenesis of synovial hyperplasia, angiogenesis, and pannus formation remains elusive to investigators. Both genetic and infectious models have been postulated and investigated. The strong association with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DR4 locus has been investigated for therapeutic and diagnostic significance. There is general agreement on the idea that genetically susceptible individuals exposed to an unknown environmental agent produce a cytokine-mediated autoimmune response that leads to the clinical manifestations seen in RA (3,40,41).

With advanced disease, a tumorlike expansion of highly invasive and immature fibroblastlike cells, or pannus, forms on the inner lining of the inflamed synovium. Cartilage destruction, in its earliest phases, occurs at the periphery of the joint where the cartilage and bone interface the invading synovial pannus. Inflammatory mediators and enzymes found in the synovial fluid sustain the continued destruction of cartilage, overlying tendons, ligaments, and bone (41). Periarticular osteopenia occurs early in the disease process. As cartilage and ligamentous support is destroyed, joint space narrowing progresses and instability may present. In the end stages of aggressive, poorly treated disease, significant bone loss and tissue attrition can cause ankylosis or a flail elbow.

JRA is a distinct entity from adult-onset RA. Currently, the cause is unknown. Although 5% to 10% will have a disease course that is similar to the adult form, in most children, the immunogenetics, clinical course, and outcomes will be different than the adult-onset disease. It is divided into three clinically distinct forms: systemic onset (Still’s disease), polyarticular JRA, and pauciarticular JRA.

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies represent a wide range of diseases involving the axial and peripheral joints. A strong association with the HLA-B27 histocompatibility complex is found in AS and Reiter’s syndrome.

Clinical Significance

A diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis is frequently made prior to presentation to the orthopedist. However, clinical suspicion should be aroused when a patient presents with symmetric polyarticular arthralgias without the typical signs of OA. Signs of systemic manifestations of inflammatory arthritides should be actively pursued if the diagnosis is unclear. Nearly two-thirds of all patients with RA will develop involvement of the elbow joint (30,31). Pain, stiffness, and loss of function in the rheumatoid elbow continue to be the most common indications for TEA (25,35, 36, 37,42).

Perhaps the most important factor to be considered prior to surgical treatment of the synovial-based arthritides is that medical therapy has been maximized. In most cases, synovial-based arthritides respond to medical remitting agents. That having been said, approximately 10% of patients with RA will have a progressive aggressive disease pattern that does not respond to current medical therapies. Many patients will present with polyarticular disease, and functional restoration should take a stepwise approach. Patients with highly aggressive rheumatoid disease, or those requiring long-term immunosuppressive medications, should be considered immuno-deficient and treated accordingly. Perioperative consultation with a medical physician should be obtained.

Surgical management of the extremity with multiple symptomatic joints deserves special consideration. Priority should be placed on the joints with the greatest pain and functional disability, or on the hand and wrist if all joints are equally symptomatic (39,47). Whether priority is placed on the shoulder or elbow when symptoms are similar is a topic of some debate. Although one report states that elbow arthroplasty should precede shoulder arthroplasty (48), Connor, Morrey, and Neel feel that in most cases, the shoulder arthroplasty should take precedence over the elbow (47,49). Deep infection after TEA or interval

glenoid bone loss could potentially preclude total shoulder arthroplasty.

glenoid bone loss could potentially preclude total shoulder arthroplasty.

Nutrition is also a concern when dealing with patients with chronic catabolic inflammatory diseases. Malnutrition, as evidenced by serum albumin, prealbumin, and transferring values, should be diagnosed and aggressively treated to maximize the intrinsically poor healing potential of these patients.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

History

At least twice as common in females, the typical presentation of RA is that of symmetric polyarticular arthralgias associated with greater than 1 hour of morning stiffness. The American College of Rheumatology has devised classification criteria for patients with RA for purposes of standardizing studies (43) (Table 23-1). Patients with the most aggressive disease class have been reported to have higher rate of deep infection after TEA (40%) than all other classes (5%) (28). A history remarkable for the use of steroid medications can give clues to the severity of disease. One study reported that 50% of the infections encountered occurred in those patients undergoing steroid therapy (27).

Physical Examination

A careful examination of the cervical spine and ipsilateral shoulder, wrist, and hand should include a thorough documentation of appearance; tenderness; effusions; motion; joint stability; nerve status; integrity of the rotator cuff and triceps; and tendon integrity across the wrist and digits.

Joint swelling and tenderness predate the appearance of deformity and motion loss. Functional loss is subjective and individual. Symmetric wrist and digital involvement with ulnar drifting of the proximal digital joints is characteristic and can further compromise the use of the effected limb. Because of its superficial nature, the presence of an effusion and pannus in the rheumatoid elbow is easily palpated and indicative of active disease.

TABLE 23-1 AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA FOR RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cervical spine instability is a well-described feature of advanced RA and should be assessed in any patient with RA prior to surgery. Even in the absence of myelopathy, lateral cervical and flexion-extension views of the cervical spine revealing basilar invagination or a posterior atlantodental interval of less than 14 mm warrant surgical spine consultation prior to management of the extremities (44).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree