Classification, Evaluation, and Nonoperative Management of Frozen Shoulder

Gita Pillai

Frances Cuomo

INTRODUCTION

Adhesive capsulitis is one of the most common yet one of the most poorly understood disorders of the shoulder. It is characterized by painful, gradual loss of glenohumeral motion resulting from progressive fibrosis and resulting in contracture of the glenohumeral capsule.

Codman first used the term “frozen shoulder,” to describe a condition of tendonitis with secondary involvement of the subacromial bursa. He described the disorder as a “condition difficult to define, difficult to treat, and difficult to explain from the point of view of pathology.”13 Neviaser, in 1945, coined the term “adhesive capsulitis” as he felt this term correlated more appropriately with the pathology seen—fibrosis, inflammation, and eventually capsular contracture.29

Adhesive capsulitis occurs in 2% to 5% of the population. The majority of affected patients are female.4 It is most frequently found in patients between the fourth and sixth decades of life.24 The nondominant extremity appears to be most often involved, with most reported cases being described as affecting the left side.12,14,23 Bilateral involvement occurs in 6% to 50% of cases, although only 14% of these cases manifest simultaneously.2,4,8,12,40

The etiology of this condition is unknown. Its development has been associated with various disorders including diabetes mellitus,6,27,28,32,48 thyroid disorders,6,48 hypoadrenalism,48 corticotrophin deficiency,11 and autoimmune disease,8 and the treatment of breast cancer.10,47 Trivial trauma has been postulated to be an important factor in the development of frozen shoulder, particularly when it is followed by a prolonged period of immobilization.14,36 Several investigators have proposed an autoimmune basis for frozen shoulder. Despite early reports, the incidence of HLA-B27 has been found not to be increased in patients with frozen shoulder.40

The true natural history of adhesive capsulitis has not been established. It has been common teaching that the disease is a selflimiting condition with a natural history lasting 1 to 3 years, while others have argued that 15% to 50% of patients have a refractory course that is unresponsive to conservative treatment.38,44

Frozen shoulder is a condition of uncertain etiology characterized by the spontaneous onset of pain with significant restriction of both active and passive range of motion of the shoulder. In this chapter, frozen shoulder will be discussed in terms of classification, evaluation, and nonoperative management.

CLASSIFICATION

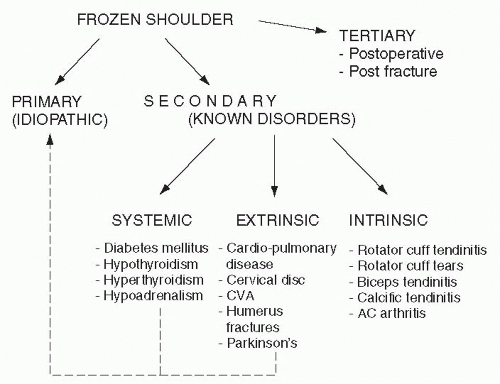

Frozen shoulder is typically classified into primary or secondary frozen shoulder (Fig. 9-1). Primary frozen shoulder is a term used to describe the process of progressive fibrosis and inflammation that occurs in the absence of any other lesions. Secondary frozen shoulder is used to describe the stiff shoulder that occurs in the presence of a known intrinsic, extrinsic, or systemic pathology.26

Secondary frozen shoulder can develop due to calcific tendonitis, rotator cuff pathology, or biceps tendon pathology. Postoperative shoulder stiffness, often called frozen shoulder, will be covered in the specific surgical chapters and its management as a postoperative complication.

Differentiating between primary disease and pain due to other pathology can be difficult. Often, patients with a small rotator cuff tear and frozen shoulder are classified as having

secondary frozen shoulder, but in reality the condition can be successfully treated as a primary frozen shoulder.

secondary frozen shoulder, but in reality the condition can be successfully treated as a primary frozen shoulder.

FIGURE 9-1. Proposed pathways for the development of frozen shoulder syndrome. AC, acromioclavicular; CVA, cerebrovascular accident. |

Adhesive capsulitis can be classified by clinical stages, arthroscopic stages, and histologic stages. Reeves originally studied the natural history of 49 cases of frozen shoulder over 10 years and identified three clinical stages—pain, stiffness, and recovery.38 Phase I consists of the insidious onset of pain with progressive stiffness that lasts 2 to 9 months. Phase II is the stiff, contracted phase that lasts 4 to 12 months. Phase III is the thawing phase where motion gradually improves over 12 to 24 months. Neviaser described four stages of adhesive capsulitis based on both the physical examination and the arthroscopic findings31 (Fig. 9-2). Hannafin subsequently did biopsies on 15 patients in varying stages of frozen shoulder (Neviaser 1-3) and correlated clinical symptoms, examination under anesthesia, arthroscopy, and histopathology.21 It is important to note that these are not discrete stages but rather a continuum of a disease process.

Stage 1 is characterized clinically by pain at the extremes of motion. If pain is relieved by lidocaine injection, range of motion is not limited. Night pain is common. Patients have typically had symptoms for less than 3 months. Diagnosis of stage 1 frozen shoulder may be difficult. Early loss of external rotation is common. Arthroscopically, one sees a fibrinous synovial inflammatory reaction, without adhesions or capsular contraction. Histopathology demonstrates hypervascular, hypertrophic synovitis, and normal capsular tissue.

Stage 2 is characterized clinically by severe night pain and decreased range of motion. This stage has been called the freezing stage.38 Motion is limited in multiple planes, forward elevation, external rotation, internal rotation, and abduction. Arthroscopy demonstrates thickened hypervascular synovitis described as having a Christmas tree appearance.31 There is some loss of the axillary fold as well. Biopsy demonstrates hypertrophic, hypervascular synovitis and perivascular, subsynovial capsular scar.

Stage 3 is characterized clinically by severe loss of motion. Pain my still be present at night and at extremes of motion. Arthroscopy demonstrates complete loss of the axillary fold and minimal synovitis. Capsular biopsy demonstrates a hypercellular, collagenous tissue with a thin synovial layer.

Stage 4, the thawing stage, is characterized by minimal pain and a gradual improvement in motion. Arthroscopy demonstrates adhesions. The amount of improvement of motion is debated.

DIAGNOSIS

Frozen shoulder represents a disease process that is diagnosed with careful history and physical examination rather than with diagnostic tests. The physician needs to take a careful history of related risk factors, especially diabetes mellitus. The physical examination is critical both in making an accurate diagnosis and in identifying the specific areas of capsular contracture.

History

Patients often report a gradual onset of pain, sometimes associated with a minor traumatic event such as putting on a coat, reaching into the backseat of a car, or a minor tug on the arm. Pain can range from minor to severe intensity and is often present for months prior to presentation. Pain typically occurs over the deltoid and may radiate into the forearm.

Pain is a critical component of the frozen shoulder condition with pain at night, pain with dressing, and pain with daily activities. Often the pain varies during the course of the disease. In the early phases patients often complain of an intense burning sensation—typically seen in the “pain” and “freezing” phases. In the early phases of frozen shoulder, the symptoms closely resemble those found in rotator cuff pathology. As the patient enters the “frozen phase,” pain occurs at extremes of motion and feels more like a dull fullness. As patients lose range of motion, activity overhead or behind the back becomes difficult to perform. The most significant loss of motion occurs in external rotation, with a smaller loss of abduction and internal rotation. Patients will complain about reaching, putting on a coat, or fastening a bra. Occasionally, patients will complain about pain in the scapular region, which is typically due to compensatory increased scapulothoracic motion.

The physician also needs to inquire about associated conditions such as diabetes, thyroid disease, CVA, and MI. The risk of frozen shoulder is much more common in the diabetic patient versus the general population with a risk of 20% as compared with 2% to 5%.19 Diabetic patients have a high incidence of bilateral symptoms (77%), and typically have poorer outcomes with treatment.19,42 In addition to inquiring about medical conditions, physicians need to inquire about medications such as barbiturates, antituberculosis agents, and protease inhibitors which have been associated with frozen shoulder.18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree