Key points

- •

Physiatrists are ideally suited to diagnose and treat whiplash injuries, provided they appreciate the sources of chronic pain for this patient population.

- •

Although most medical providers take the view that whiplash is a self-limited neck sprain/strain, peer-reviewed literature over the past 20 years gives more accurate data regarding why 20% to 30% of patients transition to chronic whiplash syndrome.

- •

Researchers have implicated the cervical facet joint as a primary pain generator in chronic whiplash. However, they continue to examine other anatomic causes, including the cervical intervertebral disc, spinal ligaments, temporomandibular joint, and paraspinal muscles, to improve clinical management of whiplash injuries.

Introduction

Whiplash injuries are common sources of chronic pain diagnosed and treated within a physiatry practice. These injuries are caused by sudden acceleration-deceleration events to the human body, most often caused by rear-end motor vehicle accidents but also by other types of collisions, slip and fall events, and sports-related injuries. An epidemiologic study in the United States in 2000 estimated that 901,442 emergency department visits in that year were for neck sprain/strain. In addition, about 28% of motor vehicle accident emergency department visits had neck sprain/strain as the predominant injury.

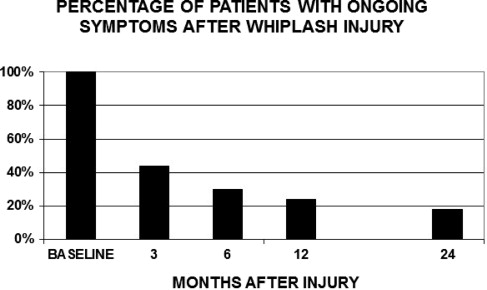

Following whiplash injuries, patients may have a variety of symptoms collectively known as whiplash-associated disorders (WADs). For many patients, symptoms resolve from within a few days up to 3 months. However, more than a third of patients who have a whiplash-type injury develop chronic pain, which is pain lasting for longer than 3 to 6 months. Radanov and colleagues published a study based on a cohort of 117 patients with WAD whom they followed from approximately 7 days after the injury until 2 years after initial injury. As shown in Fig. 1 , this analysis found that 44% of patients remained symptomatic at 3 months, 30% remained symptomatic at 6 months, 24% remained symptomatic at 1 year, and 18% remained symptomatic 2 years after the whiplash-type injury. These percentages are conservative estimates of the long-term morbidity after WAD compared with other studies.

As another example, a British study dating back to the 1980s found that more than 40% of patients were symptomatic from whiplash injuries 2 years after the date of injury. This same cohort was tracked for several years and found to have, on balance, permanent injuries. In our clinical practices, we find this 2-year mark to be a fairly accurate average time interval for patients with WAD to reach maximum medical improvement, among those who have not recovered from their injuries.

Given the prevalence of whiplash injuries and their impact on patient function, this topic warrants the attention of both specialist and primary care providers who treat patients with whiplash. This article describes the current understanding of the pain mechanisms behind common whiplash symptoms, including neck pain, headaches, back pain, upper extremity symptoms, jaw pain, and widespread pain or central sensitization. Effective treatment of these injuries is a large subject, beyond the scope of this article, which limits the focus to pain mechanisms associated with whiplash.

Although whiplash is commonly associated with neck pain, the second or third most common chronic injury among patients with WAD is lower back pain, which is sometimes called lumbar whiplash. Despite the major incidence of lumbar whiplash, this article focuses on neck and upper body symptoms and does not emphasize lower back injuries, which have received only passing epidemiologic interest without extensive research regarding the clinical biomechanics or the pathophysiology of injury.

On a final introductory note, many medical providers, including most primary care providers and surgical specialists, mistakenly assume that patients with WAD have simple neck sprains/strains and that these injuries always heal within 3 months. This assumption contrasts with research that has been done over the past 20 years examining WAD sources of pain, including the cervical facet (zygapophyseal) joints, cervical discs, paracervical muscles, and cervical spinal ligaments. Biomechanical and clinical researchers have identified specific structures—most notably the cervical facet joints—as sources of chronic neck pain after whiplash injuries, often in the setting of normal or ambiguous MRI scans.

Thus there is a large gap between the common clinical understanding of whiplash and the more accurate and specialized research dedicated to this disorder. Physiatrists are often called on to fill this gap between a cursory understanding of whiplash among other health care providers and cutting edge concepts from the pain literature.

Introduction

Whiplash injuries are common sources of chronic pain diagnosed and treated within a physiatry practice. These injuries are caused by sudden acceleration-deceleration events to the human body, most often caused by rear-end motor vehicle accidents but also by other types of collisions, slip and fall events, and sports-related injuries. An epidemiologic study in the United States in 2000 estimated that 901,442 emergency department visits in that year were for neck sprain/strain. In addition, about 28% of motor vehicle accident emergency department visits had neck sprain/strain as the predominant injury.

Following whiplash injuries, patients may have a variety of symptoms collectively known as whiplash-associated disorders (WADs). For many patients, symptoms resolve from within a few days up to 3 months. However, more than a third of patients who have a whiplash-type injury develop chronic pain, which is pain lasting for longer than 3 to 6 months. Radanov and colleagues published a study based on a cohort of 117 patients with WAD whom they followed from approximately 7 days after the injury until 2 years after initial injury. As shown in Fig. 1 , this analysis found that 44% of patients remained symptomatic at 3 months, 30% remained symptomatic at 6 months, 24% remained symptomatic at 1 year, and 18% remained symptomatic 2 years after the whiplash-type injury. These percentages are conservative estimates of the long-term morbidity after WAD compared with other studies.

As another example, a British study dating back to the 1980s found that more than 40% of patients were symptomatic from whiplash injuries 2 years after the date of injury. This same cohort was tracked for several years and found to have, on balance, permanent injuries. In our clinical practices, we find this 2-year mark to be a fairly accurate average time interval for patients with WAD to reach maximum medical improvement, among those who have not recovered from their injuries.

Given the prevalence of whiplash injuries and their impact on patient function, this topic warrants the attention of both specialist and primary care providers who treat patients with whiplash. This article describes the current understanding of the pain mechanisms behind common whiplash symptoms, including neck pain, headaches, back pain, upper extremity symptoms, jaw pain, and widespread pain or central sensitization. Effective treatment of these injuries is a large subject, beyond the scope of this article, which limits the focus to pain mechanisms associated with whiplash.

Although whiplash is commonly associated with neck pain, the second or third most common chronic injury among patients with WAD is lower back pain, which is sometimes called lumbar whiplash. Despite the major incidence of lumbar whiplash, this article focuses on neck and upper body symptoms and does not emphasize lower back injuries, which have received only passing epidemiologic interest without extensive research regarding the clinical biomechanics or the pathophysiology of injury.

On a final introductory note, many medical providers, including most primary care providers and surgical specialists, mistakenly assume that patients with WAD have simple neck sprains/strains and that these injuries always heal within 3 months. This assumption contrasts with research that has been done over the past 20 years examining WAD sources of pain, including the cervical facet (zygapophyseal) joints, cervical discs, paracervical muscles, and cervical spinal ligaments. Biomechanical and clinical researchers have identified specific structures—most notably the cervical facet joints—as sources of chronic neck pain after whiplash injuries, often in the setting of normal or ambiguous MRI scans.

Thus there is a large gap between the common clinical understanding of whiplash and the more accurate and specialized research dedicated to this disorder. Physiatrists are often called on to fill this gap between a cursory understanding of whiplash among other health care providers and cutting edge concepts from the pain literature.

Cervicothoracic pain and posttraumatic headache

The most common complaint following a whiplash-type injury is neck pain. Patients often present with nonradicular neck pain and stiffness, which on careful physical examination is documented as decreased and painful cervical range of motion as well as paracervical tenderness to palpation. Loss of range of motion is commonly thought to be caused by muscle guarding. However, patients with chronic WAD generally have decreased cervical range of motion, well beyond the expected time for muscle injury recovery, and there are likely other factors involved—including injury to the cervical facet joints, cervical intervertebral discs, and central (nervous system) amplification of pain—that contribute to chronic neck stiffness in this population.

Associated Thoracic Pain and Posttraumatic Headache

Neck pain from WAD is often accompanied by mid to upper thoracic pain and/or posttraumatic headache. Although it is probable that the thoracic region can undergo primary joint and muscle injury, this pain source has not received much attention in the WAD literature. By contrast, it is well established that lower cervical facet joint or discogenic injury cause pain referral patterns into the thoracic region (eg, Refs. ). Based on our clinical experiences and the current literature, a great portion of mid to upper thoracic pain among patients with WAD likely represents referred pain from the neck area.

Posttraumatic headache is often experienced in the occipital region with frontal and retro-orbital radiation. This headache usually arises from injury to the upper cervical facet joints, with the C2-3 facet joint in particular as a likely cause. However, astute clinicians should remember that there can be other causes for chronic posttraumatic headache in this population, including (but not limited to):

- 1.

Postconcussive headache, which often has migrainous features

- 2.

Headache associated with posttraumatic temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder

- 3.

Headache caused by injury of structures above the C2-3 facet joint, including the atlantoaxial (C1-2) joint and the greater or lesser occipital nerves

- 4.

Headache caused by internal disruption of the cervical intervertebral discs, most notably at the C2-3 level

- 5.

Headache associated with thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS), possibly caused by vertebral attachments of hypertonic scalene muscles causing abnormal forces on the facet joints

This article discusses thoracic pain and headache within the broad category of neck pain but these other potential sources should be kept within the differential diagnosis, especially among patients recalcitrant to treatment. One author (RS) in particular repeatedly humbled to finds that his patients with whiplash have headache resolution with treatment of posttraumatic TOS or TMJ disorder. Regarding postconcussive syndrome, clinicians who have a core practice treating whiplash understand that some patients have varying degrees of concomitant concussion. This subject is not covered here, but it should be considered within the differential diagnosis for posttraumatic headache.

Facet Injury

According to peer-reviewed research, the main cause of neck pain and headache among patients with chronic motor vehicle crash–related injuries is injury to the cervical facet joint. As an example of this literature, a strict double-blinded, randomized controlled trial using diagnostic cervical spinal injections (so-called medial branch blocks) was published in 1996. The investigators reported that 60% of chronic nonradicular neck pain after motor vehicle crash–related injuries was caused by cervical facet joint injury, most commonly the C2-C3 facet joint level but also throughout other levels of the cervical spine. Biomechanical and postmortem (ie, cadaveric) studies also clearly document facet injuries after simulated or actual motor vehicle crash exposure (eg, Refs. ).

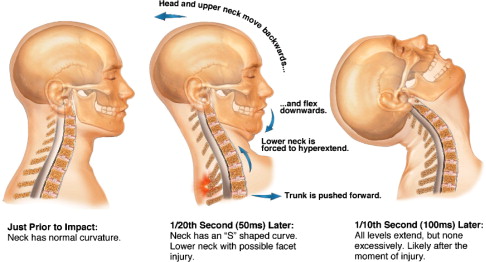

The biomechanical basis for facet joint injury began to emerge about 20 years ago in experiments that used high-speed digital image processing to detail the kinematics, or observed motion, of simulated rear-impact collisions. Using cadaveric cervical specimens subjected to laboratory motor vehicle crashes, researchers found a so-called S-shaped curve in response to rear impact for the human neck in the sagittal plane. This S-shaped curve is illustrated in Fig. 2 , which is derived from one of the first landmark studies by Grauer and colleagues in 1997.

Fig. 2 shows that, within a fraction of a second after rear impact, the upper part of the neck goes into flexion and retraction; the chin goes toward the chest and the occiput moves posteriorly with respect to the trunk. This movement creates an S shape to the neck when viewed in the sagittal plane. This finding challenged a conventional view that the neck moved into a uniform hyperextension after rear impact. Multiple investigators since this early study have verified the presence of the S-shaped curve, using postmortem biomechanical data as well as limited in vivo data with human volunteers. This response to rear impact is thought to put both abnormal compressive and tensile forces on the facet joints, providing a biomechanical basis for what is observed clinically as facet joint injury (eg, Refs. ).

There are even animal models for WAD facet joint injury. One animal model using rats has documented that carefully controlled distention of the facet joint causes central nervous system (CNS), or centrally mediated, increases in pain, consistent with clinical findings and other research discussed later.

Disc Injury

A less common source of neck pain and cervicogenic headache seen in our clinical practices and documented in the WAD literature is internal disruption to the intervertebral disc. Most patients with cervical discogenic pain do not present with radiculopathy but with axial pain and pain referral patterns either above the neck as headache or below the neck as upper back pain. Patients rarely present with radiculopathy, but much more frequently cervicobrachial symptoms are caused by TOS or other factors, as discussed later.

The scope of research to support cervical discogenic pain, in contrast with facet injury, is limited, as noted in reviews on anatomic pain generators for WAD. One reason for this decreased evidence is the inability to use noninvasive imaging or diagnostic spinal injections to provide anesthetic blockade of cervical intervertebral discs. Schellhas and colleagues in 1996 carefully correlated cervical discography with cervical MRI for patients with axial neck pain versus a control group and showed that most discogenic findings on MRI are not predictive of the cause of the pain. In the absence of cervical radiculopathy, fracture, or spinal cord injury, MRI is generally neither sensitive nor specific for pinpointing the source of pain after cervical trauma.

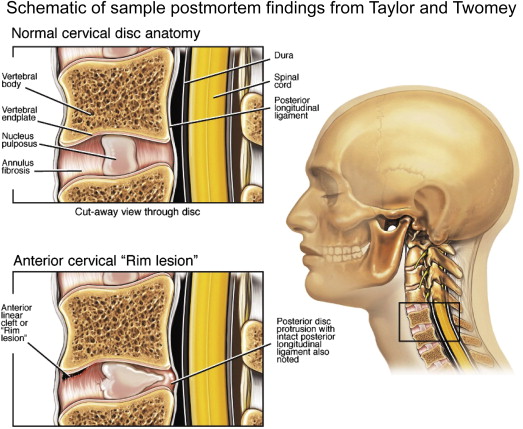

In a 1993 landmark postmortem study titled “Acute Injuries to Cervical Joints. An Autopsy Study of Neck Sprain,” Taylor and Twomey demonstrated contained disc protrusions and so-called rim lesions among patients who died in motor vehicle crashes of traumatic brain injuries but who had normal neck radiographs at the time of autopsy. One key feature of their study was to provide cadaveric specimens from a control group who died of nontraumatic causes, with the study pathologists blinded to the cause of death. Rim lesions were uniquely posttraumatic findings involving a hemorrhagic tear of the disc annulus from the adjacent vertebral endplate, likely caused by excessive tensile forces, which is thought to be one basis of discogenic injury from WAD. Fig. 3 shows the findings from this study. On a separate continent, Jonsson and colleagues published a similar study, without a control group and with more emphasis on findings at the facet joints and at the craniocervical junction.

These and other studies with cadaveric histology also help show the inadequacy of current imaging technologies (including MRI and computed tomography) for detecting these pathoanatomic lesions.

Other Sources of Cervicothoracic Pain

Cervicothoracic pain after whiplash is also hypothesized to come from primary muscle injury, spinal ligamentous injuries, and centrally mediated pain. A brief note is given to injury to the dorsal root ganglion, given an intriguing pig model that showed pressure gradients within the cervical spinal canal that might cause tissue damage at the level of the dorsal root ganglia during a simulated whiplash event. This pressure gradient decreased with the use of a head restraint mechanism in pigs, consistent with effective whiplash prevention. Centrally mediated pain is discussed later. All of this research is still in progress, and throughout readers are referred to a few recent reviews regarding anatomic pain generators in the setting of chronic whiplash injury.

Although muscle injury is not thought to be a source of chronic pain among patients with whiplash, it may indirectly influence chronic pain patterns through a variety of mechanisms, including the direct pull of muscle attachments on the facet joint capsule, chronic muscle atrophy after whiplash causing decreased neck strength and function, alterations in proprioception caused by muscle spindle injury, and other sources of aberrant neuromuscular control. Muscle injury is hypothesized to stem from the abrupt lengthening that occurs during the rapid movement of the head and neck despite reflex or active paracervical muscle activation.

As treatment providers who recognize that published research does not always reflect practice in the clinic setting, we have assisted several patients with whiplash at a plateau in their recovery by applying trigger point needling to paraspinal and periscapular muscles. However, patients with years of injury generally do not respond to this type of muscle-focused therapy. In addition, we have developed an increased respect for the role of muscle with chronic injury, given our experience with TOS, as discussed later.

Another postulated mechanism of neck pain after whiplash injury is damage to cervical spinous ligamentous structures, as discussed in several recent reviews and sample postmortem and animal studies. A 2001 cadaveric study by Yoganandan and colleagues documented injuries to the ligamenta flava and anterior longitudinal ligaments, in addition to injury to the facet joints and cervical disc annuli for whole human cadavers subjected to laboratory rear-impact collisions. The postmortem study by Jonsson and colleagues in 1991 (mentioned earlier) documented extensive spinal ligamentous injuries, in addition to facet joint and intradiscal injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree