Key points

- •

Although physiatrists are ideally suited to assess chronic pain, they need to perform a careful history and physical examination for accurate assessment.

- •

Specific attention should be given to comorbid factors, such as depression, disability, and deconditioning, at the same time searching for a treatable nociceptive focus driving the patient’s chronic pain.

- •

The examiner should avoid overreliance on medical technology in making their assessment because this approach is fraught with false-positive and false-negative pitfalls that may be harmful to the patient.

Introduction

In contrast to acute nociceptive pain, the paradox of chronic pain is that many who suffer with this condition experience amplified rather than decreased pain over time. Chronic pain is often associated with widespread functional deficits such as sleep disruption, muscle stiffness, and the loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL). Functional loss is often associated with higher level ADL, such as grocery shopping and housecleaning, but can involve more basic ADL in the setting of more severe injuries.

To put this information into context, up to 100 million Americans may suffer with chronic pain and a recent study estimated the annual burden of chronic pain, including work loss, to be more than $500 billion. Physiatrists are often first-line specialists for patients with chronic pain. This article describes a clinician’s approach to the assessment of chronic pain. The literature is replete with more theoretic discussions on the nature of chronic pain. This discussion will be more practical and grows out of years of experience as a practicing clinician.

Introduction

In contrast to acute nociceptive pain, the paradox of chronic pain is that many who suffer with this condition experience amplified rather than decreased pain over time. Chronic pain is often associated with widespread functional deficits such as sleep disruption, muscle stiffness, and the loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL). Functional loss is often associated with higher level ADL, such as grocery shopping and housecleaning, but can involve more basic ADL in the setting of more severe injuries.

To put this information into context, up to 100 million Americans may suffer with chronic pain and a recent study estimated the annual burden of chronic pain, including work loss, to be more than $500 billion. Physiatrists are often first-line specialists for patients with chronic pain. This article describes a clinician’s approach to the assessment of chronic pain. The literature is replete with more theoretic discussions on the nature of chronic pain. This discussion will be more practical and grows out of years of experience as a practicing clinician.

Clinical presentation: history

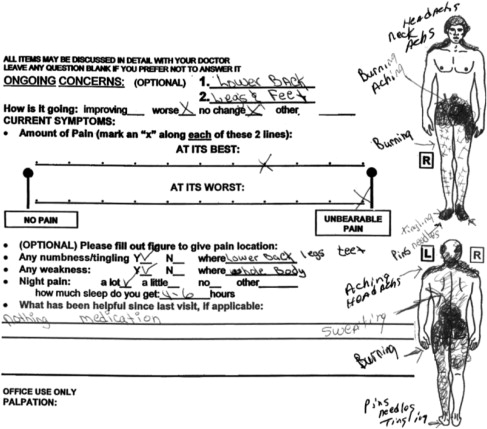

Patients who have chronic pain can be identified by several factors. Foremost, patients typically have pain of at least 3 to 6 months’ duration (and often much longer duration). Pain-body diagrams may illustrate a diffuse pain pattern, with fairly high baseline levels of visual analog scale pain. Fig. 1 illustrates a typical example for a clinic patient with severe chronic spinal pain.

The distribution of pain on the pain-body diagram may not follow any clear-cut, focal anatomic pattern. Practitioners may suspect a chronic pain syndrome for a new patient by simply scanning their pain-body diagram before entering the examination room.

Another feature of chronic pain is a significant loss of function. This loss of function can be assessed and tracked with the use of a functional index. Note, however, that simply tallying the total items of impaired function, for example with the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire, should not be considered diagnostic for identifying a patient with a generalized chronic pain syndrome. Fig. 2 illustrates such a scale for a patient who has chronic and severe, but focal, lower back pain from a specific injury. Although this impressive list of impaired function might imply a more generalized disorder such as fibromyalgia syndrome, this patient had a nociceptive focus as the source of his global decrease in function.

The Dreaded Ds

In practice, it may be helpful to collate and track the so-called dreaded Ds in assessing a patient with chronic pain. If patients have 3 or more of these features, their chronic pain often affects their daily function, their ability to work, and their quality of life. For these patients, I recommend physiatry referral, sooner rather than later. The dreaded Ds are as follows:

- 1.

Disability

- 2.

Depression

- 3.

Deconditioning

- 4.

Dependence on opioids

- 5.

Dysfunctional relationships, including divorce as a result of the patient’s loss of function and chronic pain

- 6.

Drinking and other substance abuse.

I cannot provide simple weighted averages to the various dreaded Ds. However, in my experience, vocational disability is often one of the most important factors to complicate a patient’s course of care. Patients who are unable to return to gainful employment generally do not have as good a prognosis as those who continue to work. There are no value judgments here. Rather, I offer my dispassionate view of outcomes from treating patients with traumatic injuries, mostly in the setting of personal injury and/or workers’ compensation.

Some of the dreaded Ds are likely not independent. For example, many injured patients will develop depression as a result of their loss of function. For some patients, if their function can be restored or their pain relieved, their depression will often melt away. For example, Barbara Wallis and colleagues conducted an elegant study showing resolution of depression and anxiety symptoms among patients with chronic whiplash injuries whose pain was successfully treated with facet joint neurotomy for chronic neck pain.

There are other patients who have a more complex relationship between their emotional state and their physical disability, evidenced within my clinical practice and in the literature on chronic whiplash. For example, patients who have a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may have this condition reactivated by a motor vehicle crash. In this setting, these patients often do poorly unless psychological factors can be addressed in addition to their physical pain. By contrast, others have a much more straightforward relationship between their chronic pain and their emotional state and resolve their dysphoria lock-step with improvement in pain and physical function.

Integrative Approach to the Complex Patient with Chronic Pain

In my experience, if a patient has at least 3 of the above 6 factors, usually a specialist with a physiatry approach to injury is required. In other words, if an orthopedic surgeon, for example, works with a patient who has had focal joint injuries but also more widespread problems with the dreaded Ds, the patient may well have relief of their focal joint pain from the orthopedic treatment but they are not likely to improve their functional status to the point of return to work and other functional gains.

Similarly, a chiropractor may do well to treat the patient’s spinal pain and help them avoid dependence on opioid-based pain medications. However, in my experience, they generally do not have enough scope of practice to address many of these other issues, such as disability, deconditioning, and depression. It has been my experience that the well-trained physiatrist, who is attuned to these multiple nonphysical issues, is ideally suited to treat the complex patient with chronic pain. Having physiatry training alone does not guarantee an ability to treat these larger issues. One needs to have a propensity and level of patience to identify the dreaded Ds and to formulate an integrative treatment plan.

One of the classic pitfalls I see in my clinical practice and work as an expert witness, is that patients who have experienced multiple complex injuries from major trauma are often passed from one orthopedic specialist to the next. There is no single specialist taking an overall view of the patient’s injuries and loss of function. Thus, they may get a focal shoulder consultation with surgery, then knee surgery, then foot and ankle assessment, and perhaps even physiatry spinal assessment with spinal injections given for diagnostic purposes. This barrage of specialty treatment is provided without any single provider giving an overall view of the patient’s functional status and the nonphysical barriers to rehabilitation. This pattern represents a major danger associated with the current specialized form of treatment and is one that, as physiatrists, we are naturally equipped to help prevent.

Special Case of Workers’ Compensation

In the workers’ compensation setting, I have found that the following additional dreaded Ds are relevant:

- 1.

Decision to litigate.

- 2.

Disagreement with employer.

Decision to litigate

The treating provider should not blame either the patient or the workers’ compensation claim company or employer for the presence of litigation. However, patients who decide to have legal representation in the workers’ compensation setting generally have claims that are more complex and almost always associated with chronic disability.

This association may not be coincidental because workers’ compensation attorneys generally are not paid unless the patient is on time loss. Thus, patients who are not on time loss may not find it either worthwhile or feasible to obtain legal representation in the workers’ compensation setting. In the personal injury setting, it is controversial whether litigation per se leads to a worsened outcome. Specifically, legal representation in the personal injury setting may represent the response to, rather than the cause of, worsening prognosis after chronic whiplash injuries. In other words, many patients do not bother with legal representation for the first few months after injury. However, they may seek an attorney if their injuries become more chronic.

Disagreement with employer

Again, the examiner should not take sides and decide whether the employer or the employee is to blame for a litigious or contentious claim. In my experience, if the employer and the injured worker have a mutual level of suspicion, the outcome of the claim will generally sour. For example, injured workers may be fearful that the employer will seek retaliation. Specifically, if the employer states that they are willing to have the patient return to work in a lighter duty capacity, given functional loss from a spinal injury, the worker may be concerned that they will be laid off shortly after the claim is closed. For their part, the employer may expedite claim closure by returning the patient to lighter duty employment, avoiding the expense for vocational consultation or retraining. Their offer for employment may be either in good faith or disingenuous. This uncertainty is a major source of concern for some injured workers, especially in industries in which there is no light duty, such as construction and other building trades. Because of this fear of being laid off once the claim is resolved, injured workers who are suspicious of their employers are often wary of accepting lighter duty work options. They assume, sometimes based on the experiences of their fellow injured workers, that the employer will terminate them once the claim is closed. In my experience, this problem of disagreement with employer is often one of the most important factors predicting outcome in a workers’ compensation setting. If the injured worker and the employer have a relationship of mutual respect, lighter duty work options or reasonable accommodations often emerge, and the claim may resolve successfully.

Again, the physician should try not to judge the employer or the injured worker. Instead, they should give a dispassionate rendering of medical treatment, at the same time acknowledging that the level of trust between injured worker and their employer is an important factor in the success of a claim. Although this factor may not have a direct bearing on the experience of chronic pain, the distinction between chronic pain and workers’ compensation claim-related factors can become blurred.

As an example, imagine a patient who is a pipefitter making approximately 4 times the minimum wage plus overtime and other benefits. If the pipefitter sustains a low back injury and is unable to return to their profession, he or she may be found eligible for permanent lighter duty work. In Washington State, there is no need to match patients to their previous level of earnings. This injured pipefitter might be found eligible to become a security guard, making slightly more than minimum wage. In my experience, most injured pipefitters remain reluctant to accept the career switch to security guard. Whether the patient is actually malingering or whether their behavior needs to be understood from a biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain should be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

Keep in mind that the choices for the injured pipefitter are (1) to receive 60% to 80% of their baseline wage on time loss, or more than twice the minimum wage, and remain resting at home, or (2) return to work as a security guard, with increased chances for aggravating their low back pain with return to physical activity and a significant pay cut going from time loss to working full-time. It may not be surprising from a cognitive-behavioral viewpoint, without considerations of malingering, that this injured worker may naturally feel entrenched with chronic spinal pain.

The employer may believe that the injured worker is malingering or overly invested in their disability. They may perform secret surveillance on the patient, with the goal of determining whether the patient is voluntarily underperforming or malingering. In some cases, the suspicion of excessive pain behavior with underperformance or malingering is verified, either through a functional capacity evaluation or video surveillance.

Clinical presentation: physical examination

Regarding physical examination, I note that chronic pain patients often have fairly globally reduced spinal range of motion. Lateral bending of the spine often causes contralateral paraspinal pain. For example, if patients undergo left lateral bending of the neck, they may develop right upper trapezius pain. This may be the manifestation of stiff and tightened muscles. For the cervical spine, in the setting of chronic whiplash, I often use quantitative cervical spine range of motion measurements to help track response to treatment. However, lumbar range of motion as a measure of impairment is more controversial and may not yield meaningful results.

There may be further loss of range of motion in the extremities, although generally this is limited to proximal joints, such as the shoulders and hips. In these more proximal joints, pain with range of motion is usually not localizable to an intra-articular joint problem. For example, although shoulder overhead range of motion may be limited, the resultant pain is often in the upper trapezius area, rather than in the lateral humeral area, which indicates a nociceptive focus within the shoulder joint, such as a rotator cuff tendinitis. Another example is the straight leg raise maneuver, which will often cause low back or buttock pain but not the lower extremity pain classic of lumbar radiculopathy. In fairness, the back and buttock pain may reflect a nociceptive focus, such as a discogenic pain generator, rather than a myofascial phenomenon of a painful muscle stretch.

The astute examiner should be alert to the coexistence of chronic centrally mediated pain and a focal nociceptive source of pain. For example, it is reasonable to assume that patients with chronic cervical facet-mediated pain after whiplash injuries have concomitant centrally mediated pain. Thus, a nociceptive focus can be thought of as driving a more generalized centrally mediated pain syndrome. As stated in one review on chronic whiplash pain, “The initial tissue damage and ensuing nociception may induce central hyperexcitability…This could be maintained by ongoing peripheral nociception or due to central changes that remain after resolution of the tissue injury.”

In my practice, I use simple bedside maneuvers to help me gauge whether there is centrally mediated pain or pain from peripheral sensitization from an original nociceptive focus. For example, with the patient prone, the examiner may do a test by rolling the skin over the area that has been painful, as illustrated in Fig. 3 . I believe exquisite segmental discomfort in response to this test is an indicator of centrally mediated pain or peripheral sensitization.