Abstract

Objective

We sought to establish whether chronic neck pain patients suffering from vertigo and instability have true balance disorders.

Patients and methods

Ninety-two patients having suffered from chronic neck pain for at least 3 months were enrolled in the present study. Patients with a history of neck trauma or ear, nose and throat, ophthalmological or neurological abnormalities were excluded. The patients were evaluated in a clinical examination (neck mobility) and a test of dynamic and static balance on the Satel ® platform in which mediolateral (Long X) and anterior-posterior deviations (Long Y) were monitored. Our patients were divided into three groups: a group of 32 patients with neck pain and vertigo (G1), a group of 30 patients with chronic neck pain but no vertigo (G2) and a group of 30 healthy controls.

Results

All groups were comparable in terms of age, gender, weight and shoe size. Osteoarthritis was found in 75% and 70% of the subjects in G1 and G2, respectively. Neck-related headache was more frequent in G1 than in G2 (65.5% versus 40%, respectively; p = 0.043). Restricted neck movement was more frequent in G1 and concerned flexion ( p < 0.001), extension ( p < 0.001), rotation ( p < 0.001), right inclination ( p < 0.001) and left inclination ( p < 0.001). Balance abnormalities were found more frequently in G1 than in G2 or G3. Static and dynamic posturographic assessments (under “eyes open” and “eyes shut” conditions) revealed abnormalities in statokinetic parameters (Long X and Long Y) in G1.

Conclusion

Our study evidenced abnormal static and dynamic balance parameters in chronic neck pain patients with vertigo. These disorders can be explained by impaired cervical proprioception and neck movement limitations. Headache was more frequent in these patients.

Résumé

Objectif

La question à laquelle nous avons souhaité répondre dans cette étude est de savoir si des troubles objectifs de l’équilibre existent chez les cervicalgiques chroniques se plaignant de sensations vertigineuses et d’instabilité ?

Patients et méthodes

Ont été inclus dans notre étude des patients adressés au service de médecine physique souffrant de cervicalgie chronique commune évoluant depuis plus de trois mois. Ont été exclus de l’étude les patients qui avaient des antécédents de lésions traumatiques du rachis cervical ou des anomalies aux explorations ORL, ophtalmologique ou neurologique. Chaque patient a été évalué par un examen clinique mesurant la mobilité cervicale et une évaluation instrumentale posturographique de l’équilibre statique et dynamique sur une plateforme de force Satel ® . Les paramètres recueillis et analysés sont les longueurs sur l’axe latéral (Long X) et antéropostérieur (Long Y) de déplacement du centre de pression des appuis plantaires. Nos patients ont été partagés en trois groupes : un premier groupe de 32 cervicalgiques chroniques avec sensations vertigineuses (G1), un deuxième groupe de 30 cervicalgiques chroniques sans sensation vertigineuse (G2) et un troisième groupe de 30 sujets sains (G3).

Résultats

Les trois groupes ont été jugés comparables selon l’âge, le sexe, le poids et la pointure. La cervicalgie était associée à une arthrose cervicale dans 75 % chez le G1 et dans 70 % chez le G2. Une céphalée d’origine cervicale était plus fréquente dans le G1 par rapport au G2 (65,6 % versus 40 % ; p = 0,043). Une limitation de la mobilité du rachis cervical a été constatée dans le G1 par rapport au G2 et G3. Cela a concerné tous les mouvements de flexion ( p < 0,001), d’extension ( p < 0,001), de rotations ( p < 0,001), et d’inclinaison droite ( p < 0,001) et gauche ( p < 0,001). Des troubles de l’équilibre ont été retrouvés dans le groupe G1 par rapport aux deux groupes G2 et G3. L’évaluation posturographique statique et dynamique yeux ouverts et fermés a montré des anomalies des paramètres de l’équilibre (Long X et Long Y) dans le G1 par rapport aux G2 et G3 avec des différences statistiquement significatives.

Conclusion

Notre étude montre des anomalies des paramètres de l’équilibre statique et dynamique chez des patients cervicalgiques chroniques ayant des sensations vertigineuses ou des sensations d’instabilité posturales. Ces troubles peuvent être expliqués par une altération de la proprioception cervicale et la limitation de la mobilité du rachis cervical. Une céphalée d’origine cervicale a été fréquemment associée chez ces patients.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Posture corresponds to maintenance of the body in a reference position. The mechanisms that control posture are extremely complex and involve a wide variety of structures: peripheral afferents (i.e. proprioceptive, exteroceptive, labyrinthine and visual afferents), the central nervous system (the CNS – notably the brain stem, cerebellum, basal ganglia and the hemispheres) and the effector muscles . Alterations in one of these components (such as cervical proprioception) can generate balance disorders. Degradation of cervical proprioception is often related to chronic neck pain, which is a frequent reason for consultation in rheumatology and physical medicine. Several studies have shown that deterioration of the cervical spine’s proprioceptive capacities results in perturbed postural stability control in chronic neck pain patients . The use of specific rehabilitation programmes to re-establish cervical proprioception improves balance in these patients .

With the objective of explaining the occurrence of vertigo and postural instability in chronic neck pain, we evaluated balance on a force platform in chronic neck pain patients (with or without vertigo) and control subjects. We hypothesized that the presence of balance disorders in chronic neck pain patients caused their episodes of vertigo and postural instability.

Our goal was to study balance in a population of chronic neck pain patients with or without vertigo, relative to a control group.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Patients

This was a prospective, year-long study that started in January 2006. We included all patients referred to our Physical Medicine Department for chronic (>3 months) neck pain (in the presence or absence of vertigo) linked to cervical arthritis or minor intervertebral disorders.

Vertigo was defined as an erroneous impression of the movement of objects relative to the subject or the movement of the subject relative to his/her environment, in the absence of vestibulo-ocular nystagmus.

The chronic neck pain patients were divided into two groups: a group with vertigo (G1) and a group without vertigo (G2).

These two groups were compared with a group of healthy controls (G3: hospital personnel) who had never suffered from cervical spine problems.

We excluded patients with a history of cervical spine trauma or surgery and those with abnormal results in ear, nose and throat (ENT) examinations (vestibular damage), ophthalmological tests (vision disorders) and/or neurological assessments (sensorimotor or coordination impairments).

All three groups underwent a posturographic evaluation of balance.

1.2.2

Methods

All the neck pain patients underwent a clinical evaluation, including an assessment of the pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS), a cervical spine examination (mainly focusing on cervical mobility and completed by standard X-ray imaging), a neurological assessment (evaluating the strength of the four limbs, surface and deep sensitivity and coordination) and a comprehensive ENT examination (including an electronystagmogram and a caloric test, in order to rule out potentially balance-altering vestibular damage).

For the cervical mobility measurements, we recorded the chin–sternum distance for flexion–extension, the chin–acromion distance for rotation and the earlobe–acromion distance for inclination.

An electronystagmogram was used to assess the following parameters: tracking eye movements, saccades and positional, spontaneous or head-shaking nystagmus.

The caloric test (with hot and cold water) was used to study the frequency and speed of reflex reactions in each ear.

In the absence of abnormal clinical examination and test results, we considered that a patient’s vertigo or feelings of instability were non-vestibular.

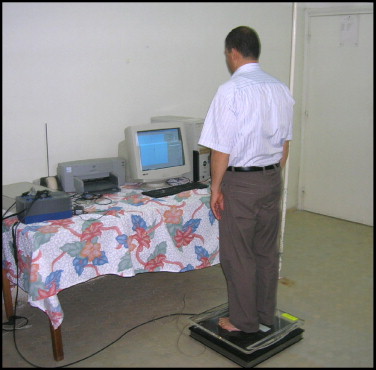

In addition to these examinations, our patients underwent a posturographic evaluation of static balance ( Fig. 1 ) and dynamic balance ( Fig. 2 ) on a Satel ® force. The latter measures displacements of the foot’s centre of pressure over time and generates a set of parameters which reflect balance – the most important being the lateral (Long X) and anteroposterior (Long Y) displacements of the foot’s centre of pressure.

The posturographic analysis of static balance was performed using a flat, rigid plate resting on three force sensors ( Fig. 1 ).

The patient was instructed to stand as still as possible on the platform and to look horizontally at a wall about 1.5 m in front (there was no particular visual target). There were two experimental conditions: “eyes open” and “eyes shut”. Each sequence lasted 51.2 s and the data acquisition frequency was 40 Hz. The base of support did not move and was not deformed. The recording was started once the subject was ready. In the event of problems, trials were repeated.

A posturographic analysis of dynamic balance was performed using a plane-cylindrical stabilometer with a single degree of freedom. A 48 cm × 48 cm balance board was placed on the force platform ( Fig. 2 ). The two parallel arcs on the underside of the board had a radius of curvature of 55 cm and an apex height of 6 cm. The subject stood on the board in order to successively measure lateral and anteroposterior balance in each of two conditions (eyes open and eyes shut). The subject was instructed to keep maintain the plate as horizontal as possible. The measurement period lasted 25.6 s and the data acquisition frequency was again 40 Hz.

Each patient thus underwent a total of six posturographic assessments: static, dynamic lateral and dynamic anteroposterior balance tests in the “eyes open” and “eyes shut” conditions.

We monitored lateral displacements (Long X) and anteroposterior displacements (Long Y). The anthropometric variables measured for each patient were age, gender, weight, height and shoe size.

1.2.3

Statistics

The results for quantitative variables (Long X and Long Y) were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare quantitative balance parameters. If a significant difference was present, the three groups were compared pair-wise in a post-hoc test (least squares difference). We used a χ 2 test to compare frequencies. The significance threshold was set to p = 0.05.

To compare each group’s mean values of the balance parameters (Long X and Long Y) in the “eyes open” condition with those in the “eyes shut” condition in the static, lateral dynamic and anteroposterior dynamic balance tests, we used a paired Student’s test.

1.3

Results

Groups G1 and G2 comprised 32 and 30 patients, respectively. The control group (G3) comprised 30 healthy subjects.

In order to eliminate potentially balance-altering factors other than chronic neck pain, the three groups were compared in terms of age, height, weight, shoe size and gender; there were no statistically significant differences.

Table 1 summarizes mean values of the anthropometric parameters for each group and the p value for the inter-group comparisons.

| Age (years) | Height (m) | Weight (kg) | Shoe size (French system) | % Women | % With arthritis | % With MID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 48.15 | 1.64 | 70.31 | 39.65 | 68.75 | 75 | 25 |

| Group 2 | 47.1 | 1.61 | 69.16 | 38.86 | 76.66 | 70 | 30 |

| Group 3 | 47.13 | 1.63 | 69.63 | 38.9 | 83.33 | – | – |

| p | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

In terms of the cause of neck pain, the patient distribution (arthritis or minor intervertebral disorders) was similar in G1 and G2 ( Table 1 ). The frequency of cervical arthritis in G1 and G2 was 75% and 70%, respectively, but this difference was not statistically significant. The mean time since onset of neck pain was 21.53 months in G1 and 29.63 months in G2.

The mean neck pain intensity on a VAS was 6.65 out of 10 in G1 and 4.03 in G2 ( p < 0.001).

Moreover, cervical spine mobility was significantly lower in G1 than in G2 and G3 ( p < 0.001); this primarily concerned flexion, extension, rotation and right and left inclination.

The amplitudes of all these movements and p values from intergroup comparisons are given in Table 2 .

| Flexion | Extension | Right rotation | Left rotation | Right inclination | Left inclination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 2.09 | 16.65 | 12.71 | 12.62 | 10.12 | 10.21 |

| Group 2 | 1.1 | 18.33 | 9.06 | 9.26 | 7.86 | 8 |

| Group 3 | 1.01 | 19.58 | 8.12 | 8.22 | 7.42 | 7.64 |

| p | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

The main balance parameters evaluated were Long X and Long Y. We observed abnormalities in these parameters in G1 (compared with G2 and G3) under all test conditions ( Tables 3–5 ).

| Eyes open | Eyes shut | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long X | Long Y | Long X | Long Y | |

| Group 1 | 312.04 ± 116.67 | 402.10 ± 169.92 | 408.92 ± 168.05 | 690.34 ± 288.48 |

| Group 2 | 218.48 ± 69.48 | 303.32 ± 80.78 | 253.39 ± 83.60 | 382.13 ± 108.65 |

| Group 3 | 221.21 ± 56.03 | 317.85 ± 96.54 | 265.02 ± 110.41 | 412.77 ± 134.66 |

| p | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Eyes open | Eyes shut | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long X | Long Y | Long X | Long Y | |

| Group 1 | 486.21 ± 165.78 | 407.50 ± 106.33 | 892.53 ± 235.85 | 764.89 ± 233.70 |

| Group 2 | 349.13 ± 84.03 | 312.22 ± 99.56 | 743.73 ± 177.27 | 611.66 ± 184.91 |

| Group 3 | 379.09 ± 91.00 | 311.46 ± 74.90 | 852.55 ± 307.30 | 559.26 ± 115.02 |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Eyes open | Eyes shut | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long X | Long Y | Long X | Long Y | |

| Group 1 | 312.82 ± 167.25 | 602.57 ± 270.75 | 575.66 ± 193.65 | 1146.61 ± 359.05 |

| Group 2 | 222.20 ± 62.35 | 471.14 ± 140.92 | 374.32 ± 126.24 | 864.97 ± 217.17 |

| Group 3 | 241.31 ± 75.27 | 483.04 ± 120.44 | 400.70 ± 130.40 | 857.33 ± 205.11 |

| p | 0.005 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

There were statistically significant mean Long X and Long Y differences between G1 on one hand and G2 and G3 on the other, in all the static and dynamic tests. There was no significant difference between G2 and G3.

By comparing the parameters in each test (static, dynamic mediolateral and dynamic anteroposterior tests) in the “eyes open” condition compared with “eyes shut”, we observed a number of statistically significant differences ( p < 0.05) between the three groups.

Furthermore, we did not find any significant correlations between neck pain intensity and balance parameters in G1 or G2. The same was true of the time since pain onset. In contrast, a neck-related headache was noted in 65.6% of the patients in G1 and in only 40% in G2. This difference was statistically significant ( p = 0.043).

1.4

Discussion

Balance results from a multimodal mechanism involving visual, vestibular and proprioceptive receptors which send information to the CNS via specialized afferents. This information is integrated by CNS structures whose efferent pathways then modulate muscle tone and trigger the postural adaptations required for the maintenance of posture or coherent movement. The latter factors must be under control at all times, in order to correct for and adjust to a new situation. If the various components of the sensory information are discordant, the subject experiences a sensation of imbalance . Perturbation of cervical proprioception can alter balance. In the present study, we addressed the question of whether true balance disorders exist in chronic neck pain patients suffering from vertigo or instability. Causes which have been described in this respect include torticollis, acute and chronic neck pain (primarily that observed during cervical arthritis), post-trauma neck pain and cervicobrachial neuralgia, which can led to neck spasms. In the present study, the patients had chronic neck pain related to either cervical arthritis or minor intervertebral disorders. Signs of cervical arthritis (arthritis of the discs and, potentially, the unvertebral joints) were found in 24 of the 32 chronic neck pain patients with vertigo in G1. Minor intervertebral disorders were diagnosed in eight patients. In G2 (30 chronic neck pain patients without vertigo), signs of cervical arthritis were found in 21 patients and minor intervertebral disorders were observed in nine patients.

Sensations of instability have been linked to neck-related headaches . In the present study, the proportion of patients suffering from neck-related headaches was significantly greater in G1 than in G2. These headaches are often unilateral and accompanied by signs and symptoms of C2-C3 cervical spine damage .

Vertigo and instability are related to neck extension and rotation, suggesting primarily benign, paroxysmal, positional vertigo or vertebrobasilar insufficiency. In the present study, all the neurological results were normal; there was neither nystagmus nor vestibular impairment. The ENT examination, caloric test, electronystagmographic analysis and auscultation of the cervical blood vessels did not reveal anomalies in any of our neck pain patients (regardless of whether or not they experienced vertigo).

Furthermore, frontal and lateral plain radiographs of the cervical spine and the atlanto-occipital joint ruled out the presence of bone malformations (such as basilar compression and Arnold-Chiari malformation) associated with the compression or malformation of neighbouring nervous structures.

Cervical MRI and/or CT imaging in seven of the G1 patients revealed signs of spinal canal narrowing in five cases and signs of disc-root conflict in two cases, together with arthritis.

The performance of vertebral arteriography is sometimes necessary when a doubt exists as to vertebrobasilar impairment and when justified by the intensity of the vertigo. None of our patients required this type of investigation.

In order to explain the occurrence of episodes of vertigo in chronic neck pain patients, we look for objectivised balance disorders related to alterations in cervical proprioception and which might underlie vertigo or instability.

Patients with neck pain were less able to correctly sense neck position than the control patients, indicating an alteration in cervical proprioception . This clinical evaluation enabled selection of patients requiring proprioceptive rehabilitation.

Furthermore, in order to assess our starting hypothesis, we evaluated our patients’ balance on the Satel ® platform. This investigation evidenced true balance disorders in patients in G1. These disorders were expressed in terms of the statistically significant inter-group differences in the mean displacements on the lateral axis (Long X) and the anteroposterior axis (Long Y) .

In a study of 266 neck sprain patients free of bone damage (on X-rays) and instability in dynamic imaging , 75% were found to have a cervicoscapulocephalic syndrome which generally featured vertigo and a drunken sensation when standing. The authors suggested the existence of neck-induced, proprioceptive, afferent non-compliance in the postural control system following apparently benign trauma.

Experiments performed by the same authors on monkeys subjected to accelerations with hyperextension trauma provided histological evidence of damage to the anterior soft tissues of the neck (due to stretching), the posterior soft tissues around the joint surfaces, joint capsules and posterior joints and the lower neck muscles (due to sudden hyper-coaptation). The latter muscles are particularly rich in proprioceptive sensors which play an essential role in tonic posture control.

In the same context, Lavignolle et al. performed a posturographic study on 126 patients with neck pain resulting from benign neck trauma and confirmed the existence of postural stabilization disorders in 118 subjects.

None of our neck pain patients had experience cervical trauma per se ; indeed, the majority (62.5%) were suffering from arthritis-related damage.

Consequently, cervical arthritis could (like trauma) result in postural disorders responsible for vertigo and a sensation of instability.

In a series of 12 patients with chronic neck pain (whether resulting from trauma or not), Faux et al. demonstrated a correlation between functional complaints and posturographic parameters.

Likewise, Norre et al. and Alund et al. have objectivised balance disorders by using posturography in chronic neck pain patients with vertigo.

Other authors have shown the existence of postural disorders (as measured on a force platform) in patients with cervical dystonia or torticollis, when compared with a control group. However, these disorders were only apparent during “eyes open” and “eyes shut” dynamic tests and not during a static evaluation .

The results of our study (static and dynamic posturographic measurements on the Satel ® platform under “eyes open” and “eyes shut” conditions) confirm the literature data. Although posturography does not provide any information on the aetiology or the exact anatomical location of the damage, it can highlight the deficient balance system .

What, then, is the physiopathological explanation? We know that there are cervical proprioceptive receptors which inform the balance centres of the positions of the cervical spine and the head; these receptors are situated in the upper part of the cervical spinal column (particularly in the posterior joint capsules and the perivertebral muscles) . Posterior joint dysfunction or a muscle spasm could perturb the operation of these receptors – leading to alteration of the proprioceptive message and vestibulo-oculocervical coordination and thus a disorganised motor pattern.

Vertigo- and instability-like postural disorders can be observed in subjects with chronic neck pain: when vestibular tests give normal results, one can legitimately assume that the postural disorders are related to functional or structural damage to neck proprioceptive receptors.

The differences in mean Long X and Long Y values in each group and in each test (static tests and mediolateral and anteroposterior dynamic tests) in the “eyes open” condition compared with the “eyes shut” condition also testifies to the contribution of vision to postural stabilisation.

In chronic neck pain patients, vertigo and a sensation of instability are often preceded or accompanied by headaches related to upper neck problems. If the vertigo is not associated with headaches, it should not be linked with cervical causes ; in fact, the highest neuromuscular bundle densities are found in the small, suboccipital muscles .

Taken as a whole, these data support a neck-related cause for certain episodes of vertigo, as Long as the damage is situated in the upper cervical spine. This type of vertigo is accompanied by spinal signs (pain and stiffness) . In fact, the cervical spine plays a decisive role in posture, in view of its proprioceptive qualities and its relationship with vision and the vestibular system .

Another hypothesis for explaining balance disorders in neck pain patients with vertigo relates to limited cervical spine mobility and thus a restricted visual field during neck movement. In fact, eye-head movement coupling means that whenever the eyes move by more than 15° in the horizontal plane, a reflex neck movement shifts the visual target towards the retinal fovea and enables more detailed analysis. Neck stiffness can lead to eye-head decoupling, due to weak interaction between the oculomotor and suboccipital muscles . The work by Karlberg and Madeleine argue in favour of this hypothesis ; physiotherapy reduces pain and increases cervical mobility and postural control, as evaluated by posturography .

On the therapeutic level, vertebral manipulation can be useful for minor intervertebral disorders .

In cases of cervical arthritis, one must treat the pain, stiffness and, above, cervical spasms by infiltration of the myofascial trigger points , relaxing massage and physiotherapy .

Rehabilitation is of major value, with the use of postural reflex techniques and postural adjustment with eye-neck coupling .

1.5

Conclusion

Our posturographic study with the Satel ® force platform confirmed the existence of objectivised static and dynamic balance disorders in chronic neck pain patients suffering from vertigo and sensations of instability. Moreover, we demonstrated the frequent association of neck-related headache in these patients and limited cervical spine mobility, which may result in impaired cervical proprioception and the occurrence of balance disorders.

These considerations justify the more widespread use of rehabilitation in the therapeutic management of chronic neck pain patients with vertigo. The rehabilitation programme should primarily include techniques for increasing suppleness and re-establishing eye-neck coupling.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Une posture correspond au maintien du corps dans une position de référence. Les mécanismes qui contrôlent cette posture sont extrêmement complexes et leur démembrement met en évidence la contribution de structures très variées à savoir les afférences périphériques (proprioceptives, extéroceptives, labyrinthiques et visuelles), les centres (tronc cérébral, cervelet, ganglions de la base, hémisphères cérébraux) et les effecteurs musculaires . L’altération de l’une de ces composantes dont la proprioception cervicale peut générer des troubles de l’équilibration. L’atteinte de la proprioception cervicale est souvent en rapport avec une cervicalgie chronique qui est un motif fréquent de consultation en milieu de rhumatologie et de médecine physique. Plusieurs études ont mis en évidence que la détérioration de la capacité proprioceptive du rachis cervical est à l’origine des perturbations du contrôle de la stabilité posturale des patients ayant une cervicalgie chronique . La restauration de cette proprioception cervicale par une rééducation spécifique améliore l’équilibre de ces patients .

Dans le but d’expliquer la survenue des sensations vertigineuses et d’instabilité posturale en cas de cervicalgie chronique nous avons évalué l’équilibre par plateforme de force chez des patients cervicalgiques chroniques avec ou sans sensation vertigineuse et des sujets témoins. Nous posons comme hypothèse que la présence de troubles de l’équilibre chez les patients cervicalgiques chroniques serait à l’origine de ces sensations vertigineuses et d’instabilité posturale.

Notre objectif a été d’étudier l’équilibre dans une population de cervicalgiques chroniques avec ou sans sensation vertigineuse par rapport à un groupe témoin.

2.2

Patients et méthode

2.2.1

Patients

Notre étude est prospective ; elle s’est déroulée en une année à partir de janvier 2006. Ont été inclus dans cette étude tous les patients adressés au service de médecine physique ayant une cervicalgie chronique commune avec ou sans sensation vertigineuse évoluant depuis plus de trois mois en rapport avec une arthrose cervicale ou un dérangement intervertébral mineur.

Une sensation vertigineuse a été définie par l’impression erronée de déplacement d’objets par rapport au sujet ou du sujet par rapport à son environnement sans nystagmus vestibulo-oculaire.

Ces patients ont été partagés en deux groupes : un premier groupe G1 de cervicalgiques chroniques avec sensation vertigineuse et un deuxième groupe G2 de cervicalgiques chroniques sans sensation vertigineuse.

Ces deux groupes ont été comparés à un troisième groupe témoin G3 comportant des sujets sains (personnels de l’hôpital) n’ayant jamais souffert de leur rachis cervical.

Ont été exclus de l’étude les patients qui avaient des lésions traumatiques ou une chirurgie du rachis cervical et les patients qui avaient des anomalies aux explorations ORL (atteinte vestibulaire), ophtalmologique (troubles de la vision) et/ou neurologique (déficit sensitivo-moteur ou de la coordination).

Ces trois groupes ont bénéficié d’une évaluation posturographique de l’équilibre.

2.2.2

Méthodes

Tous nos patients cervicalgiques ont bénéficié d’une évaluation clinique comportant une évaluation de la douleur cervicale par une échelle visuelle analogique (EVA), un examen du rachis cervical précisant surtout la mobilité cervicale et complété par des radiographies standard, un examen neurologique évaluant la force des quatre membres, la sensibilité superficielle et profonde, la coordination et un examen ORL complété systématiquement par un électronystagmogramme et une épreuve calorique afin d’éliminer une atteinte vestibulaire pouvant altérer l’équilibre.

Pour la mesure de la mobilité cervicale, nous avons utilisé la distance menton–sternum pour la flexion–extension, la distance menton–acromion pour les mouvements de rotation et la distance lobule de l’oreille–acromion pour les inclinaisons.

Les paramètres qui ont été analysés par l’éléctronystagmogramme sont la poursuite oculaire, l’épreuve de saccades, les tests optocinétiques, la recherche d’un nystagmus spontané ou provoqué par head shaking et le nystagmus positionnel.

L’épreuve calorique (eau chaude et eau froide) a étudié la réflectivité de chaque oreille en fréquence et en vitesse.

Des sensations vertigineuses ou d’instabilité ont été considérées d’origine non vestibulaire devant la normalité de l’examen clinique et de ces épreuves.

À côté de ces examens, nos patients ont bénéficié d’une évaluation posturographique sur une plateforme de force Satel ® pour l’étude de l’équilibre statique ( Fig. 1 ) et dynamique ( Fig. 2 ). C’est un matériel qui permet de mesurer les déplacements du centre de pression plantaire en fonction du temps. Il fournit un ensemble de paramètres qui reflètent l’équilibre dont les plus importants sont : les longueurs sur l’axe latéral (Long X) et antéropostérieur (Long Y) de déplacement du centre de pression plantaire.