Abstract

Objectives

Identify key informational and educational items (“messages”) to provide to physicians (general practitioners and specialists) and physiotherapists for the management of pain induced by exercise and mobilization (PIEM). Develop checklists to improve this management in daily practice.

Material and methods

The Delphi method for consensus-building was used to identify informational and educational messages for health professionals who deal with PIEM. Informed by the results of an extensive qualitative study, a panel of experts from 5 medical and paramedical disciplines concerned with PIEM and a representative of a patients’ association were interviewed individually and iteratively in order to obtain a single, convergent opinion.

Results

Delphi consultation helped to determine 9 areas corresponding to 54 key messages of information and education for doctors and physiotherapists who deal with PIEM. These messages relate to: defining, characterizing, identifying, and evaluating PIEM; identifying factors that may cause or increase this pain; informing the patient in order to avoid misinterpretation of PIEM; preventing and treating PIEM; and dealing with it during physical therapy sessions. The method also enabled us to develop 2 synthetic instruments (checklists) — 1 for physicians and 1 for physiotherapists — to help with the management of this pain.

Conclusion

Consulting a panel of experts comprising different categories of actors dealing with PIEM on the basis of a thorough qualitative diagnosis in order to identify messages for a training program makes it possible to harmonize programs with the expectations of patients and the problems encountered by professionals. The formulation of this program and the institutionalization of two checklists should enable health professionals to identify, qualify, and deal more effectively with PIEM.

1

Introduction

1.1

Pain management, a major focus of public health policy

Since the 1994 report by Senator Neuwirth on postoperative pain in France, pain management has become a priority in efforts to improve the quality of care. Pain was in fact recognized by the Law on patients’ rights and quality of the health system of 4 March 2002 and established as a priority in Law No. 2004-810 of 13 August 2004 on health insurance. Four national action plans against pain — 1998–2000 , 2002–2005 , 2006–2010 and 2013–2017 1

1 The 2013–2017 plan has not yet been implemented.

— have been adopted, with the second and the fourth plans according specific consideration to medical care-related pain.This focus on pain successfully responds to patients’ expectations , and pain management has been defined as a basic right of healthcare users, assigning health professionals the responsibility of preventing, evaluating, and treating pain . Neglecting to treat pain (physical and mental) may now expose hospitals to liability and legal action, and medico-legal disputes may well lead to convictions of hospitals and compensation for plaintiffs .

1.2

Care-related pain, a neglected form of pain

Care-related pain, although very common, is still downplayed today . Defined as “short-term pain caused by the physician or a therapist in predictable circumstances that may be prevented by appropriate measures” , this pain can occur in different circumstances: pain generated by basic care or nursing (toilet, bandages, dressing and undressing, transfers…); by procedures that are most often invasive (punctures, injections, insertion of catheters…); by treatments (surgery, pharmacology, radiotherapy, physiotherapy…); or by medical studies . Performed for the patients’ “good”, the acts or procedures that cause pain may be minimized or disregarded by the caregivers who prescribe or administer them , an attitude that underscores the need for recognition and prevention.

1.3

Physical therapy programs, an increasingly widespread therapeutic option

PIEM is one form of pain related to therapeutic actions. It is becoming more significant in that supervised exercise is used more extensively in programs for chronic painful conditions, and in developed countries, the prevalence of chronic diseases continues to increase .

In France, the 2007-11 Plan for improving the quality of life for people with chronic diseases estimated that “15 million people, nearly 20% of the population, are living with chronic disease”. With a longer lifespan, the number of people affected by chronic diseases is constantly increasing. The need for more attention to people with these diseases has been affirmed at both the national and international levels.

Exercise is one of many recommendations for managing chronic pain conditions, but no specific human or therapeutic support for dealing with the pain that may be induced by these treatments is ever mentioned. None of the 25 recommendations of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International relating to the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis mentions PIEM when patients are encouraged to perform regular joint mobilization exercises. Similarly, the recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) for managing hip osteoarthritis , those relating to non-pharmacological treatments for hip and knee osteoarthritis , and those for spondyloarthritis by the French Rheumatology Society call for non-pharmacological treatment based on physical exercises and mobilization but do not mention the painful implications of these physical therapy programs.

1.4

Pain induced by physical therapy programs, detrimental for patients

In addition to ethical and regulatory considerations, induced pain can indeed be harmful for patients. Painful treatments and care procedures performed without attention may cause some to abandon their care programs. Not only can neglecting treatment undermine the trust that patients have in their healthcare, it can also lead to non-adherence to treatments and medication .

1.5

Improving the information and training of health professionals: a path of progress in the management of physical therapy programs

Improving the information and training of health professionals has been shown to be an important part of pain management in the various national plans for combatting pain and in health policy regulation (Handbook of the Ministry of Health and Welfare in association with the French Society for the Study and Treatment of Pain ; recommendations by AFSSAP, HAS, and ANAES on managing chronic headaches , migraine , postoperative pain in oral and maxillofacial surgery , and recommendations by practitioners ).

In connection with PIEM, a socio-anthropological qualitative study of patients’, doctors’, and physical therapists’ views revealed both prescribers’ disregard for PIEM and also differences among patients, doctors, and physiotherapists regarding this specific type of pain and its management . By identifying weak points in therapeutic practices and in caregiver-patient relationships in this area, this study confirmed that some health professionals, including physiotherapists, GPs, and specialists who prescribe physical therapy programs, were in need of information and training. This study also provided the relevant qualitative database to develop a training program that corresponds to patients’ expectations and the problems encountered by these professionals.

We therefore designed a new study relying on the results of the qualitative study previously performed in order to identify key information and education items (“messages”) to provide to general practitioners, specialists and physiotherapists for the management of PIEM and to develop checklists to improve this management in daily practice.

2

Material and Methods

2.1

Medical ethics

The protocol for this study was submitted to the Ethics Committee (Comité de protection des personnes “Île-de-France I”), which found that it was “an observational study outside the scope of the Public Health Act on the protection of persons participating in biomedical research”.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient who was a member of the panel of experts received oral and written information in compliance with current regulations, which do not impose obtaining written consent in this type of study.

2.2

The Delphi method for consensus-reaching

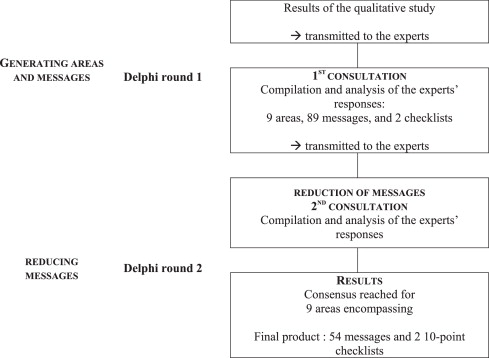

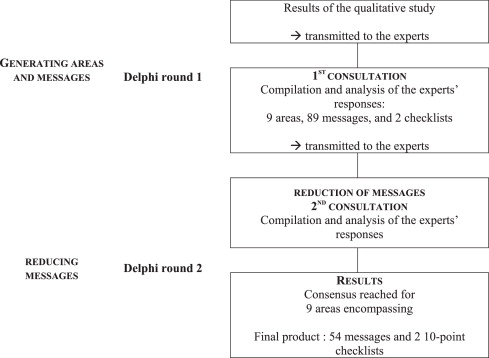

The content of the information and education program was determined using the Delphi method for consensus-reaching . This method provides a procedure of collective decision-making to obtain the opinion of a panel of experts on a specific topic. The experts go through successive rounds of questions in order to elicit one single, final, convergent opinion from the group. Because the experts are questioned iteratively and individually, this method guarantees the independence of their responses. The Delphi study process ended with a two-round process, shown in Fig. 1 .

2.3

The steering committee and the panel of experts

The steering committee included three experts — two clinicians, both rheumatologists and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians (S.P., C.P.), and the sociologist (S.A.) who conducted the qualitative investigation on PIEM mentioned above.

The panel of experts included multiple stakeholders concerned with PIEM — 8 doctors, 2 physiotherapists, and 1 patient — to reflect the diversity of views on this pain. Doctors were recruited from general medicine (2), patients’ first recourse, rheumatology (1), physical medicine and rehabilitation (3), and geriatrics (2). Two private physiotherapists and a patient, a member of an association dealing specifically with pain management, were also selected.

2.4

The communication process

The experts were able to participate in the study via e-mail, fax, or mail. Ten experts chose e-mail and one chose mail as their means of exchange and communication.

2.5

Producing messages

The Delphi method was used first to produce “messages” or content items, and then to select the most relevant among them .

The Delphi first round served to determine what information was relevant in composing informational and educational materials for caregivers. Two documents were sent to each of the experts: a detailed report of the results of a qualitative study previously conducted on the subject and a brief presentation of the main results of this survey . The experts were asked to use the two documents to help formulate their proposals for the content and format of the training materials. These proposals were designed to reflect the deep convictions of each expert. To help the experts, 15 different areas of thought were proposed ( Table 1 ). These areas were identified by the steering committee on the basis of the qualitative study results. The experts were invited to provide proposals both on the content of the training program and on the forms of the materials and their mode of distribution. The experts were then instructed to propose 10 to 20 specific messages for each area listed in the documents. They were also encouraged to make other suggestions that did not fall within any of the suggested areas.

| After reading the documents that you received, what content elements should be included in these materials? | |

|---|---|

| Physiopathology of pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 1 | Educational messages about the pathophysiology of PIEM (information on induced pain, its causes, underlying mechanisms…) |

| Specific education concerning pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 2 | Recognizing PIEM |

| Area no. 3 | Facilitating patients’ articulation of PIEM |

| Area no. 4 | Presenting techniques used in physical therapy programs that cause pain (program contents, types of exercises likely to be performed and likely to be painful…) |

| Area no. 5 | Presenting scientific recommendations for this area |

| Evaluating pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 6 | Assessing PIEM and using assessment instruments (scales, questionnaires…) |

| Treating pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 7 | Preventing and treating PIEM using non-pharmacological treatments (drug classes, pharmacokinetics, drug interactions…) |

| Area no. 8 | Preventing and treating PIEM using pharmacological treatments (physiotherapy, massages, relaxation…) |

| Area no. 9 | Dealing with PIEM during physical therapy sessions |

| Area no. 10 | Optimizing adherence to treatments prescribed in PIEM management |

| Area no. 11 | Proposing a checklist for the proper management of PIEM |

| Based on your own experience, what form(s) should the materials take and how should they be distributed? | |

|---|---|

| Form(s) | |

| Area no. 12 | These information and education materials for PIEM are intended for prescribers of these programs (GPs and specialists) as well as physiotherapists who carry them out. Should there be one or several forms for this? If more than one, what materials for what audience (brochure, website, application…)? |

| Area no. 13 | What is the most important visual content to include in these informational materials? |

| Area no. 14 | Should self-assessment elements be included for messages in these materials (quiz…)? If so, which ones and how? |

| Modes of distribution | |

| Area no. 15 | How should these materials be presented and advertised (place, time, method of contact with target audiences; contents of the presentation; varying the media; associated forums…)? |

2.6

Selecting the proposed messages

Each message generated was submitted to all the experts for evaluation. They were asked to rate both the relevance of the item (Do you believe that this message should be included in the final checklist?) and its formulation (Do you think that the wording of this message is appropriate?), on two 10-point Likert scales. The proposed messages were independent of each other, precise, and quantifiable. For each proposed area, the experts could add messages that they felt were important but missing.

This second round was designed to consolidate the list of messages and to identify which of them the experts found important enough to include in a training document to improve management of the PIEM. The experts could justify their choices, add to the list of proposals under evaluation, and reformulate the proposed messages.

2.7

Analysis of the data

After the Delphi first round, the proposals made by the experts were aggregated and duplicates were removed by the steering committee.

After the second round, statistical analysis of the experts’ propositions examined the areas of convergence (median) and the spread of opinions (interquartile range, extreme values).

Based on these two sets of statistical data and on the observations made by the experts in the two rounds, the members of the steering committee eliminated messages with insufficient consensus, aggregated the content of some related messages, and reformulated or developed others.

2

Material and Methods

2.1

Medical ethics

The protocol for this study was submitted to the Ethics Committee (Comité de protection des personnes “Île-de-France I”), which found that it was “an observational study outside the scope of the Public Health Act on the protection of persons participating in biomedical research”.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patient who was a member of the panel of experts received oral and written information in compliance with current regulations, which do not impose obtaining written consent in this type of study.

2.2

The Delphi method for consensus-reaching

The content of the information and education program was determined using the Delphi method for consensus-reaching . This method provides a procedure of collective decision-making to obtain the opinion of a panel of experts on a specific topic. The experts go through successive rounds of questions in order to elicit one single, final, convergent opinion from the group. Because the experts are questioned iteratively and individually, this method guarantees the independence of their responses. The Delphi study process ended with a two-round process, shown in Fig. 1 .

2.3

The steering committee and the panel of experts

The steering committee included three experts — two clinicians, both rheumatologists and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians (S.P., C.P.), and the sociologist (S.A.) who conducted the qualitative investigation on PIEM mentioned above.

The panel of experts included multiple stakeholders concerned with PIEM — 8 doctors, 2 physiotherapists, and 1 patient — to reflect the diversity of views on this pain. Doctors were recruited from general medicine (2), patients’ first recourse, rheumatology (1), physical medicine and rehabilitation (3), and geriatrics (2). Two private physiotherapists and a patient, a member of an association dealing specifically with pain management, were also selected.

2.4

The communication process

The experts were able to participate in the study via e-mail, fax, or mail. Ten experts chose e-mail and one chose mail as their means of exchange and communication.

2.5

Producing messages

The Delphi method was used first to produce “messages” or content items, and then to select the most relevant among them .

The Delphi first round served to determine what information was relevant in composing informational and educational materials for caregivers. Two documents were sent to each of the experts: a detailed report of the results of a qualitative study previously conducted on the subject and a brief presentation of the main results of this survey . The experts were asked to use the two documents to help formulate their proposals for the content and format of the training materials. These proposals were designed to reflect the deep convictions of each expert. To help the experts, 15 different areas of thought were proposed ( Table 1 ). These areas were identified by the steering committee on the basis of the qualitative study results. The experts were invited to provide proposals both on the content of the training program and on the forms of the materials and their mode of distribution. The experts were then instructed to propose 10 to 20 specific messages for each area listed in the documents. They were also encouraged to make other suggestions that did not fall within any of the suggested areas.

| After reading the documents that you received, what content elements should be included in these materials? | |

|---|---|

| Physiopathology of pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 1 | Educational messages about the pathophysiology of PIEM (information on induced pain, its causes, underlying mechanisms…) |

| Specific education concerning pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 2 | Recognizing PIEM |

| Area no. 3 | Facilitating patients’ articulation of PIEM |

| Area no. 4 | Presenting techniques used in physical therapy programs that cause pain (program contents, types of exercises likely to be performed and likely to be painful…) |

| Area no. 5 | Presenting scientific recommendations for this area |

| Evaluating pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 6 | Assessing PIEM and using assessment instruments (scales, questionnaires…) |

| Treating pain induced by physical therapy programs | |

| Area no. 7 | Preventing and treating PIEM using non-pharmacological treatments (drug classes, pharmacokinetics, drug interactions…) |

| Area no. 8 | Preventing and treating PIEM using pharmacological treatments (physiotherapy, massages, relaxation…) |

| Area no. 9 | Dealing with PIEM during physical therapy sessions |

| Area no. 10 | Optimizing adherence to treatments prescribed in PIEM management |

| Area no. 11 | Proposing a checklist for the proper management of PIEM |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree