Cardiac Rehabilitation

INTRODUCTION

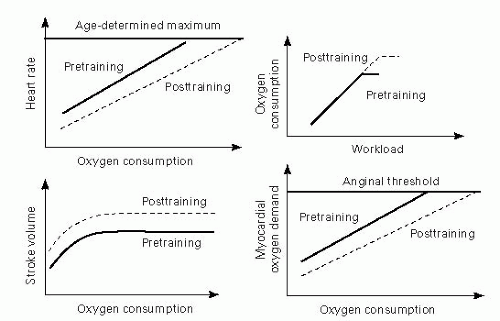

Under the broadened scope of the recent AHRQ guidelines, CR may include exercise programs, education and risk factor modification for secondary prevention, and psychosocial counseling.1 CR is indicated after acute MI, coronary revascularization, and cardiac transplantation or in patients with CHF or chronic stable angina. CR improves Vo2max, peripheral O2 extraction, ST depression, exercise tolerance, subjective sense of well-being, and return to work rates. It also lowers BP, resting HR, and myocardial O2 demand. In addition, CR has been shown to improve glycemic control and cause favorable lipoprotein changes (reducing TG and elevating HDL levels). Long-term moderate exercise in CR has been demonstrated to increase the quantity of mitochondrial enzymes in “slow twitch” muscle fibers and development of new muscle capillaries. Angiographic studies have shown reduced atherosclerotic lesions in stable angina patients undergoing intensive physical exercise and on low-fat diet over 1 year without lipid-lowering agents2 (It should be noted that it has been traditionally stated that CR does not raise [improve] anginal threshold, whereas angioplasty and CABG can.) (Fig. 13-1).

Adapted from Braddom RL, ed. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1996. |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In 1997, 1.1 million Americans were diagnosed with acute MI, and 800,000 patients underwent coronary revascularization.4 Limited data suggest that CR is a cost-effective use of medical care resources1; however, only 10% to 20% of appropriate candidates are thought to participate in formal CR programs.4 In the Medicare claims analysis for hospitalizations during 1997 of over 250,000 persons older than 65 years, CR use was only 13.9% in patients hospitalized for acute MI and 31% in those who underwent CABG. Women, the very elderly, nonwhites, and patients with multiple comorbidities were even less likely to receive CR.5 Low participation may be due to geographic factors and a failure of physicians to refer patients, particularly the elderly and women.

PHASES OF CR

Phase I – The inpatient training phase can begin from days 2 to 4 of hospitalization and typically lasts ≈1 to 2 weeks. Goals include prevention of the sequelae of immobilization, education and risk factor modification, independent self-care activities, and household distance ambulation on level surfaces. Protocol-limited submaximal stress testing is often done in uncomplicated patients prior to d/c as a guideline for outpatient ADLs and simple household activities.

Phase II – The output training phase starts 2 to 4 weeks post-d/c and typically lasts 8 to 12 weeks. Goals include increasing cardiac volume (CV) capacity and gradually returning to normal activity levels. A functional exercise tolerance (ECG stress) test is typically done 6 to 8 weeks of the postcardiac event (which allows time for the formation of a stable scar over the infarcted area) to guide the exercise prescription and determine eligibility for resuming work and sex.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree