Capsular Repair for Recurrent Posterior Instability

Edward V. Craig

James E. Tibone

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Posterior instability is not as common as its anterior counterpart. It usually occurs in young athletic population (1, 2, 3) and presents as a recurrent posterior subluxation rather than as a true recurrent posterior dislocation, which is rare.

Posterior instability itself is not an indication for surgical repair. Approximately two-thirds of patients with posterior instability respond to a proper exercise program (4) consisting of exercising the external rotators of the shoulder (the infraspinatus, teres minor, and posterior deltoid muscles) and the scapula stabilizers. Such a program will usually decrease the symptoms, but the instability may remain. No patient with instability who has not had 6 months of a structured exercise program should have surgery.

Athletes commonly present with posterior instability that interferes with their athletic endeavors (1, 2, 3). Surgical procedures geared solely to enabling them to perform at a high athletic level are usually unsuccessful. An athlete who does not respond to a conservative program will rarely be improved by operative repair if his or her only goal is to return to a high level of overhead activity. Thus, the indications for surgical repair in the athlete are pain and instability that interfere with activities of daily living. The primary indication for surgical repair is the demonstration of recurrent, symptomatic, unidirectional subluxation that has failed to respond to a comprehensive nonoperative program.

Two other clinical syndromes merit discussion and caution. True unidirectional posterior subluxation may not be as common as multidirectional instability with demonstrable posterior subluxation. Each patient with posterior subluxation should be evaluated for multidirectional or global instability, and if this is present, rehabilitation should be aimed at all directions of laxity. If nonoperative treatment fails, the operative technique must include stabilizing all directions of laxity and may require an extensive inferior capsular shift from either posterior or combined anterior and posterior directions. In addition, there are some patients, often with multidirectional instability, who have had an overly tight anterior repair that leads to gradually increasing symptomatic posterior instability. In these patients, especially if external rotation has been limited by the prior surgery and anterior tightness seems to be the predominant pathology, an anterior approach with subscapularis lengthening to restore humeral head centralization on the glenoid may be more effective than a posterior approach to tighten the soft tissue.

The second clinical syndrome that should be addressed is seen in the patient with a (suprascapular) nerve injury and weakness of the supra- and infraspinatus. Posterior subluxation in this patient may be related to weakness of the dynamic muscular stabilizers. Attention should be paid to the primary nerve injury and subsequent rehabilitation of the muscle groups rather than to tightening the posterior capsule, because without posterior muscular stabilization, the capsular repair will likely stretch out over time.

A posterior capsular repair alone is contraindicated in a ligamentously lax individual or in a patient with multidirectional instability. If surgery is indicated, these patients need a capsular shift procedure. Bony abnormalities

are rare in the shoulder with posterior instability, but a congenital hypoplastic glenoid with abnormal version would be another relative contraindication to a capsular repair and may be an indication for glenoid osteotomy. In addition, any individual with significant degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint is often made symptomatically worse by a capsular repair, which would overconstrain the shoulder and increase the degenerative changes. In line with this, the apparent posterior subluxation associated with osteoarthritis is secondary to asymmetric glenoid wear and should not be confused with recurrent posterior subluxation.

are rare in the shoulder with posterior instability, but a congenital hypoplastic glenoid with abnormal version would be another relative contraindication to a capsular repair and may be an indication for glenoid osteotomy. In addition, any individual with significant degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint is often made symptomatically worse by a capsular repair, which would overconstrain the shoulder and increase the degenerative changes. In line with this, the apparent posterior subluxation associated with osteoarthritis is secondary to asymmetric glenoid wear and should not be confused with recurrent posterior subluxation.

A relative contraindication is seen in a patient who, although lax and able to posteriorly subluxate the shoulder, does not have enough symptoms to warrant surgical repair or in a patient who has not undergone a supervised formal trial of rehabilitation. Additionally, a patient who has had prior posterior surgery with attendant damage to either the posterior cuff muscles or the suprascapular nerve is unlikely to benefit from further soft-tissue surgery posteriorly.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A typical patient with posterior subluxation has had a traumatic event with an injury occurring while the arm is in a position below shoulder level. Often, there is a direct blow from the anteroposterior (AP) direction followed by recurrent symptomatic subluxation. The patient, having suffered a significant single traumatic episode, may have had repeated episodes of microtrauma with gradually progressive stretching of the soft-tissue structures until the shoulder begins to subluxate.

A patient with posterior shoulder instability feels the shoulder slip, pop, or “click out and click in.” These instability episodes often occur with the arm in the frontal plane and may occur dynamically. Dynamic subluxation occurs as the patient begins to raise the arm upward; it reaches a point in the arc where the shoulder slips posteriorly, and as the arc of elevation is continued, relocation occurs. Thus, the patient may be able to demonstrate the posterior subluxation when asked. The posterior instability may or may not be painful.

In some patients with this type of dynamic posterior subluxation and relocation, the scapula may appear to “wing” as the humerus subluxates posteriorly. This is not true scapula winging such as that accompanying long thoracic nerve palsy and serratus anterior paralysis. Rather, it appears to be a type of scapula muscle dysfunction, of which the patients may have some control. The medial border of the scapula separates slightly from the chest wall as the head subluxates. In fact, manual stabilization of the scapula against the chest wall may actually prevent this dynamic subluxation from occurring. Thus, there may be a role for scapula muscle rehabilitation or even biofeedback techniques to “teach” the scapula to “set” properly against the chest wall. While formal surgical procedures to fix the scapula to the chest wall might theoretically appear an attractive option, these are unpredictable as procedures to control posterior subluxation in this small subset of patients with dynamic subluxation and scapula mechanic alteration.

The most important preoperative assessment is to document that the patient has an isolated posterior instability rather than a posterior instability as a component of multidirectional instability (5). On examination, care should be taken to elicit signs of generalized ligamentous laxity, which may be a clue to the presence of multidirectional shoulder instability. Hyperextensibility of the elbows, hyperflexibility of the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand, and laxity of the contralateral shoulder all may indicate the presence of global laxity. Attempts should be made to center the humeral head in the glenoid by a load-and-shift test and to subluxate the shoulder anteriorly, posteriorly, and inferiorly. The hallmark physical finding of multidirectional instability is a sulcus sign. These findings may be elicited either in the office or under anesthesia, when less patient guarding occurs, and are an additional argument for a complete examination under anesthesia and arthroscopy before an instability reconstruction, whether open or arthroscopic.

The patient who has isolated posterior instability often can be subluxated in a posterior direction by the examiner who grasps the humeral head and pulls directly backward, with the muscles of the shoulder relaxed. This load-and-shift test, or posterior drawer test, is positive in the posterior direction but negative in the contralateral shoulder. The examiner may also be able to demonstrate posterior subluxation as the arm is brought into the frontal plane at 90 degrees and internal rotation force is applied.

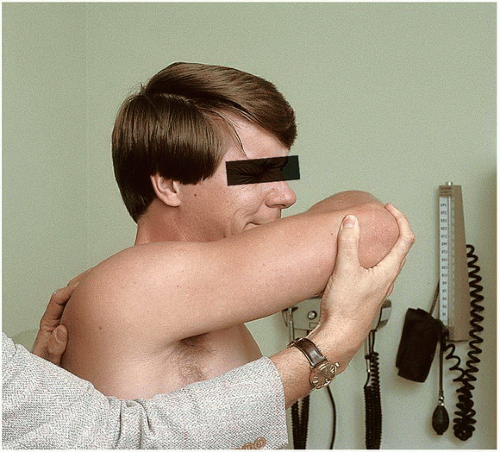

Posterior apprehension, although uncommon, should be tested. The arm is brought into forward elevation with internal rotation, and posterior stress is applied (Fig. 22-1). A sense of instability, significant pain, or painful subluxation is suggestive of the diagnosis. Range of motion of the shoulder is usually not limited either passively or actively in the patient with isolated posterior subluxation. Strength of the rotator cuff muscles may be normal, but it is not uncommon to see significant external rotation weakness when manually tested, a finding that may emphasize the need for further rehabilitation.

The diagnosis of posterior instability may be confusing, and the athlete with posterior subluxation may have other causes of shoulder pain. Therefore, before considering posterior capsular repair, it is most helpful if the patient identifies the pain while the shoulder is being subluxated as the precise pain leading to the disability of the shoulder. If posterior subluxation by the examiner can be elicited but does not produce pain in the shoulder or a sense by the patient of “that’s it; that is what I feel,” the diagnosis should be questioned and an alternative cause of the pain should be considered.

Shoulder radiographs for instability include an AP in internal and external rotation, a lateral view, and a West Point axillary view. While these views rarely show any bony changes in the glenoid, there may be some bone

reaction along the posterior rim, which will increase the clinician’s comfort level with the diagnosis. It is unusual to have a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. Occasionally, a dynamic radiograph may be taken as the patient voluntarily subluxes the shoulder, and this film may show the humeral head in a posteriorly subluxed position. Additional imaging studies include computed tomography, arthrography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A welldone, excellent-quality MRI, however, may show labral changes, capsular damage, or abnormalities of glenoid cartilage that may aid in the diagnosis. In some patients, a detachment of the posterior labrum may be identified through an imaging study, such as a gadolinium-enhanced MRI, after a particularly significant traumatic event.

reaction along the posterior rim, which will increase the clinician’s comfort level with the diagnosis. It is unusual to have a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. Occasionally, a dynamic radiograph may be taken as the patient voluntarily subluxes the shoulder, and this film may show the humeral head in a posteriorly subluxed position. Additional imaging studies include computed tomography, arthrography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A welldone, excellent-quality MRI, however, may show labral changes, capsular damage, or abnormalities of glenoid cartilage that may aid in the diagnosis. In some patients, a detachment of the posterior labrum may be identified through an imaging study, such as a gadolinium-enhanced MRI, after a particularly significant traumatic event.

If there is any doubt about the direction or extent of instability, an examination under anesthesia with arthroscopy may clarify the predominant direction of instability and address the presence or absence of intra-articular labral pathology. If arthroscopic evidence of an anterior Bankart lesion exists, the diagnosis of isolated posterior instability must be questioned.

SURGERY

The patient is placed under general anesthesia and positioned in the lateral decubitus position with the operative shoulder superior (6). The patient is held in this position with a beanbag and kidney rests. The down leg is padded to prevent pressure on the peroneal nerve (Fig. 22-2). Arthroscopy is performed before the posterior reconstruction to assess the articular cartilage and to rule out an associated anterior labral tear, which would contraindicate the posterior procedure. A sterile shoulder wrap is used and the patient is placed in 10 lb of traction with a conventional shoulder holder. The arthroscopy is performed through a conventional posterior and/or anterior portal. The rotator

interval capsule can also be treated arthroscopically, which can help decrease posterior translations and augment the open repair. After the arthroscopy is completed, the patient is released from traction and the arm is rested at the side with the patient in the same lateral decubitus position. Reprepping and draping are usually not necessary.

interval capsule can also be treated arthroscopically, which can help decrease posterior translations and augment the open repair. After the arthroscopy is completed, the patient is released from traction and the arm is rested at the side with the patient in the same lateral decubitus position. Reprepping and draping are usually not necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree