Calcaneus

Patrick Yoon

INDICATIONS

Fracture Characteristics

Traditionally, percutaneous treatment of calcaneus fractures has been reserved for tongue-type fractures. In this type of fracture, there is direct bony continuity between the posterior aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity and the posterior facet of the subtalar joint, and the entire posterior facet is depressed as one contiguous fragment. This makes it possible to reduce the posterior facet by manipulating the tuberosity with a pin and using the Essex-Lopresti technique.1, 2 and 3 A successful maneuver results in correction of both Bohler’s and Gissane’s angles, reduction of heel axial alignment into neutral or slight valgus, restoration of the normal relationship between the posterior facet of the calcaneus with the corresponding articular surface of the talus, and reduction in the calcaneal width.

There are certain other clinical situations in which this and other percutaneous techniques can be used successfully in the treatment of joint-depression calcaneus fractures. Individual surgeon experience as well as careful patient selection are both important factors in using this technique successfully. Although some authors use these techniques routinely for all Sanders II and III fractures, whether they be joint-depression or tongue-type4 or even all displaced calcaneus fractures,5, 6 and 7 it should be noted that other authors use them only for Sanders II fractures.8,9 Others reserve these techniques for patients who would not normally be candidates for extensile open procedures due to smoking or other comorbidities. When these techniques are used for non-tongue-type fractures, an anatomic reduction is more difficult to achieve. There is a steep learning curve, and the surgeon must be adept at obtaining and interpreting intraoperative fluoroscopic lateral, Harris, and Broden’s views. Subtalar arthroscopy to confirm a percutaneous reduction8,9 is also a useful adjunct. No matter which method one chooses to obtain and confirm the percutaneous reduction, this technique is more challenging than performing an extensile incision and directly manipulating the fracture and visually confirming the reduction.

There is no universal agreement as to which fractures are best treated percutaneously. A spectrum of opinions exists as to how far the indications can be safely and effectively stretched. In the author’s opinion the further the indications are widened, the less anatomic the results one will have to consider acceptable. Given these limitations, there are some individual fracture patterns in which percutaneous treatment can result in successful correction of deformity. These patterns include the following.

Tongue-type fractures in which there are direct anterior-to-posterior continuity between the entire posterior aspect of the tuberosity and the entire posterior facet. These fractures are the classic indication for percutaneous treatment (Fig. 15.1).

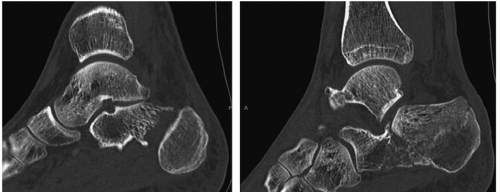

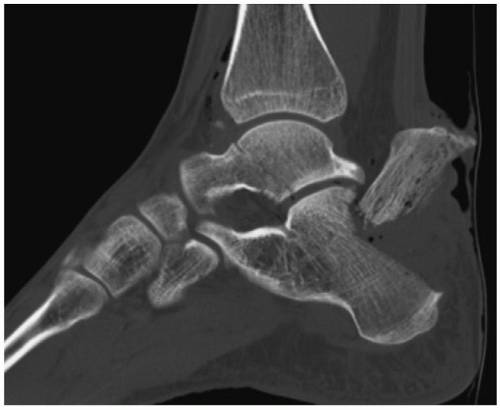

Partial tongue-type fractures in which there is a sagittal plane split in the posterior facet continuing into the tuberosity, but continuity remains between a portion of the tuberosity and the posterior facet. This continuity should be confirmed with sagittal CT reconstructions (Fig. 15.2) or with the coronal reconstructions. As with tongue-type fractures, the partial tongue fragment is always lateral with respect to the sustentacular, or constant, fragment. Percutaneous treatment for these fractures is more amenable if the partial tongue fragment is large compared to the constant fragment. For example, a Sanders IIB would be easier to reduce than a Sanders IIA as there is a larger fracture fragment with which to work. It is important to note that only the portion of the posterior fragment that is in direct continuity with the tuberosity is reducible with the Essex-Lopresti technique.

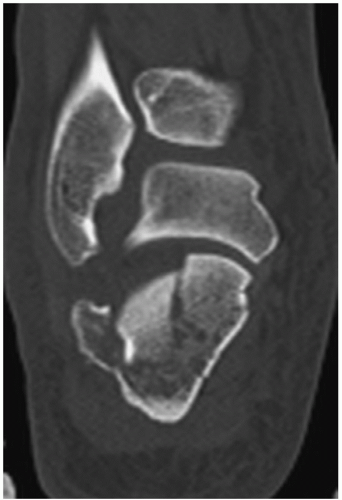

Joint-depression fractures with minimal displacement between the tuberosity and the depressed posterior facet fragment. In these situations, whatever displacement there is between the posterior facet and the tuberosity is simply accepted, and the two fragments are reduced together using an Essex-Lopresti maneuver as if they are one fragment (Fig. 15.3).

Sanders IIB and IIC joint-depression-type fractures. Joint-depression fractures in which the fragment is large enough to be maneuverable with a percutaneous joystick or tamp. The larger the fragment, the easier and more successful percutaneous reduction attempts will be (Fig. 15.4).

Displaced extra-articular tuberosity fractures not involving the posterior facet (Fig. 15.5).

Patient Characteristics

Patients with fractures that may optimally be treated with a standard extensile open incision may be candidates for percutaneous treatment if an open approach would pose an undue risk for wound necrosis or deep infection. This may include patients with diabetes mellitus, tobacco use, peripheral vascular disease, or severely traumatized lateral skin.

Contraindications

Because the incisions are small stab wounds the surgeon does not have to wait for swelling to diminish; in fact, if percutaneous reduction is to be performed it should be done as soon

as possible once the patient is medically stable. Furthermore, fractures with delayed presentation will be more difficult to reduce percutaneously due to organized hematoma interposed at the fracture site. Because the fracture site is not directly exposed, hematoma, bone fragments, or other debris may prevent an adequate reduction and are more difficult to move after 5 to 7 days.3 Some authors have reported success with protocols extending percutaneous treatment up to 14 or 19 days8,9 though presentation after 10 days was a factor in 3 of the 5 failures of percutaneous treatment in one series.9 The author has no strict cutoff for percutaneous treatment but recommends it be performed as soon as possible; operative fractures more than 1 week old are preferably treated with an open technique.

as possible once the patient is medically stable. Furthermore, fractures with delayed presentation will be more difficult to reduce percutaneously due to organized hematoma interposed at the fracture site. Because the fracture site is not directly exposed, hematoma, bone fragments, or other debris may prevent an adequate reduction and are more difficult to move after 5 to 7 days.3 Some authors have reported success with protocols extending percutaneous treatment up to 14 or 19 days8,9 though presentation after 10 days was a factor in 3 of the 5 failures of percutaneous treatment in one series.9 The author has no strict cutoff for percutaneous treatment but recommends it be performed as soon as possible; operative fractures more than 1 week old are preferably treated with an open technique.

Figure 15.3 Joint-depression fracture with minimal displacement between the tuberosity and the depressed posterior facet fragment. |

Figure 15.5 Displaced extraarticular tuberosity fragment. These fractures can be reduced percutaneously or through the often associated open wound. |

Figure 15.6 Skin necrosis on the posterior heel 1 week after an unreduced, displaced tongue-type fracture. |

Particular attention should be given to tongue-type fractures when the tongue fragment tents the posterior heel skin; if not promptly reduced this can cause varying amounts of soft tissue compromise including full-thickness skin necrosis in one study.10 For this reason, the author recommends emergent reduction for tongue-type fractures that tent the posterior skin (Fig. 15.6). If the fracture cannot be surgically treated immediately, the fracture should be splinted with the ankle in equinus to minimize the posterior skin embarrassment.10

Sanders IV fractures have a poorer prognosis with osteosynthesis regardless of the type of approach and are particularly difficult with a percutaneous approach. Several reports on the percutaneous treatment of calcaneus fractures have shown inferior results with Sanders IV fractures5,6 and some authors restrict this technique to Sanders II fractures only.9 The author recommends that caution be used when contemplating percutaneous treatment for Sanders III and IV fractures. Although extenuating clinical circumstances may make this a reasonable alternative, anatomic reduction is less likely, creating a higher risk of subtalar arthritis and the need for subtalar fusion.11

PATIENT POSITIONING

For unilateral fractures, the patient lies in the lateral position with the operative side up. (For bilateral fractures, patients are placed in the prone position with the leg currently being operated on externally rotated.) Hip positioners (Stulberg hip positioners, Innomed, Savanna, GA) are used to support the anterior superior iliac spine anteriorly and the sacrum posteriorly. This is preferable to a beanbag because it facilitates mobilization of the leg. The author uses a lateral foam positioning device (Bone Foam, Bone Foam, Inc, Plymouth, MN) to create a flat operative surface for the up (operative) limb and to protect the down (nonoperative) limb. A thigh tourniquet is placed although it is not routinely inflated. The entire lower extremity up to the thigh tourniquet is prepped and draped to facilitate knee flexion and hip rotation. C-arm is brought in from the posterior aspect of the calcaneus. The three required images are as follows.

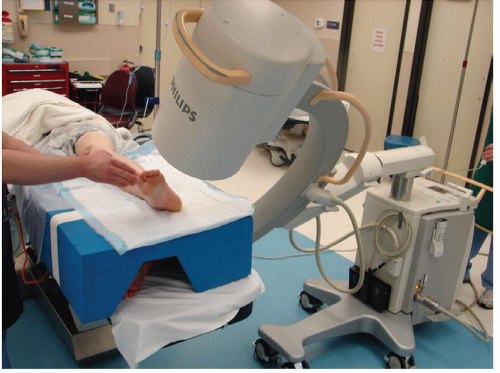

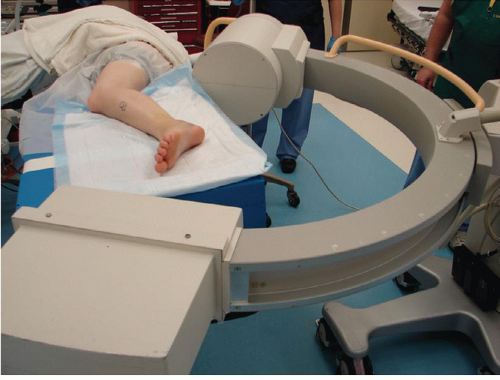

Lateral view. The lateral views are obtained with the image source below the table and the image intensifier above the patient (Fig. 15.7).

Broden’s views. The Broden’s views are taken by externally rotating the extremity. With the foot in internal rotation, images are taken with varying amounts (10 to 40 degrees) of caudad angulation of the beam. These are used to visualize various portions of the posterior facet (Fig. 15.8).

Axial (Harris) view. This view is taken by returning the foot to its resting position, lateral side pointing upward, and then tilting the entire c-arm sideways so that the image source is at the foot of the table and the image intensifier is just behind the buttock or upper thigh. A sterile sheet is used to cover the image source at the foot of the table. The image is then taken at a 45-degree angle to the calcaneal tuberosity by shooting from the foot of the table, through the calcaneus, and then posteriorly and proximally toward the image intensifier (Fig. 15.9).

During the reduction maneuver, flexion of the knee facilitates distal translation of the calcaneal tuberosity (and thereby elevation of the posterior facet) for tongue-type fractures. As this tends to place the operative limb posteriorly, it will help to have the nonoperative limb positioned slightly anteriorly to avoid superimposing c-arm images (Fig. 15.10).

SURGICAL APPROACHES

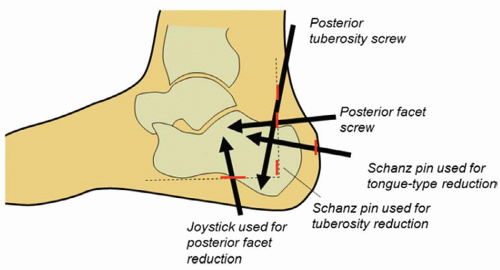

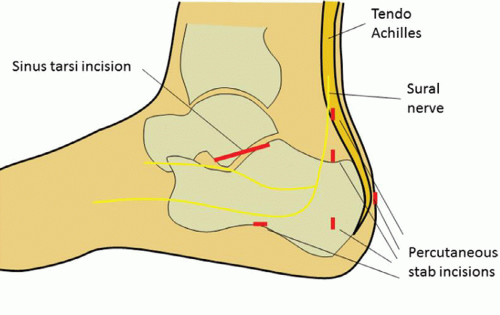

Before making any incisions the standard L-shaped extensile lateral incision12,13 is drawn on the lateral heel with a sterile pen in the event the percutaneous technique needs to be converted to an open procedure. The author typically makes multiple, small percutaneous stab incisions for this type of procedure. When practical, it is helpful to make these incisions in line with the L-shaped drawing (Fig. 15.11). If percutaneous attempts to reduce the posterior facet are unsuccessful, the stab wounds can be incorporated into the extensile incision. The typical stab incisions used are as follows: (1) Just lateral/anterior to the tendo Achilles, proximal to the tuberosity, through which superior-to-inferior screw is placed to secure a tongue fragment to the plantar portion of the tuberosity. (2) Slightly inferior to this, just superior to the top of the tuberosity, through which the posterolateral-to-anteromedial posterior facet screw(s) are placed. (3) At the posterior-inferior corner of the tuberosity, through which a Schanz pin is typically placed. These three stab wounds are typically along the vertical limb of an extensile L-shaped incision. (4) Along the inferior border of the calcaneus, through which joysticks or tamps can be inserted to elevate the posterior facet. (5) Not all the incisions can always be incorporated into the L-shaped template. For example, the posterior-to-anterior screws for a tongue-type fragment are typically made on the posterior aspect of the heel.

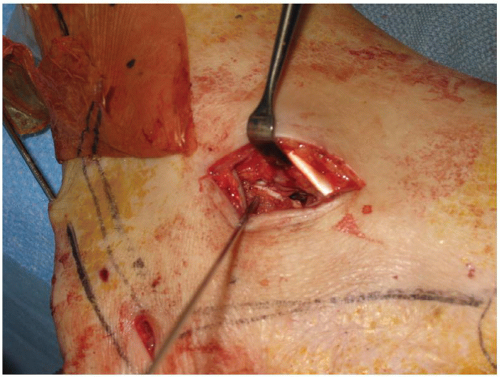

Occasionally, if the surgeon is having difficulty reducing, accessing, or visualizing a smaller depressed posterior facet fragment, a small sinus tarsi window can be used to directly approach the posterior facet. This is typically a 3- to 5-cm incision made in line with an imaginary line drawn from the tip of the fibula to the base of the fourth metatarsal (Fig. 15.12).

After incising the skin, care should be taken to protect a branch of the sural nerve, which typically crosses close to this region obliquely in a posterior/inferior to anterior/superior direction (Fig. 15.13). This incision can be extended to varying degrees anteriorly or posteriorly to access more of the subtalar joint. Various fixation devices such as screws alone or small plates can be placed directly along the lateral aspect of the posterior facet through this incision.

After incising the skin, care should be taken to protect a branch of the sural nerve, which typically crosses close to this region obliquely in a posterior/inferior to anterior/superior direction (Fig. 15.13). This incision can be extended to varying degrees anteriorly or posteriorly to access more of the subtalar joint. Various fixation devices such as screws alone or small plates can be placed directly along the lateral aspect of the posterior facet through this incision.

REDUCTION TECHNIQUES

A partially threaded 5-mm Schanz pin is useful for many of these fractures. The author typically uses a Schanz pin in three locations: From posterior to anterior in the tongue fragment as a joystick for the Essex-Lopresti maneuver, from superior to inferior in the tuberosity to lever the tuberosity away from the impacted posterior facet, and from lateral to medial to translate the tuberosity medially and pull the tuberosity out of varus (Fig. 15.14). Other useful instruments include a bone tamp, a small periosteal elevator, and Kirschner wires. Specialized equipment in selected circumstances includes a small joint arthroscope to perform subtalar arthroscopy or an inflatable balloon tamp (InflateFX, Medtronic Spine, Minneapolis, MN).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree