Baseline Program

Todd Stitik

Marc C. Hochberg

An estimated 21 million adults, or 12% of the U.S. population aged 25 to 74 years, have signs and symptoms of osteoarthritis (OA), making this group of conditions a major public health concern among the musculoskeletal diseases.1 OA may affect any of the diarthrodial joints in the body; the most common extremity joints that are involved and cause individuals to come to clinical attention are the knee, hip, and small joints of the hands and feet.

Once the diagnosis of OA is established, the development of a therapeutic program needs to take into consideration the different symptoms, signs, and functional limitations when different joints are affected, which implies different therapeutic options.2 The correlation of pain severity, functional limitation, and impaired health-related quality of life with the extent of structural changes as measured by the radiograph is only modest; hence, management decisions should not be made solely on the presence and severity of radiographic changes.3 The basic therapeutic program summarized in this chapter focuses on nonpharmacologic measures of management, stressing a team care approach that touches on the educational, physical, and social needs of the patient with OA.

Management Objectives

The goals of management of the individual patient with symptomatic OA are to 1) control pain so that the patient reaches an acceptable symptom state, 2) reduce functional limitation and disability, 3) improve health-related quality of life, and 4) avoid over-treatment with potentially harmful pharmacologic agents.

Guidelines have been proposed for management of OA at the knee and the hip4,5,6,7,8,9; the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) is presently involved in updating and harmonizing these recommendations with the goal of publication in 2007 (Nuki G, personal communication). Recommendations published by the European League of Associations of Rheumatology (EULAR) include a series of ten propositions with a supporting evidence-based review of randomized clinical trials.8,9 The first recommendation stresses that “The optimal management of OA requires a combination of nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatment modalities.” Furthermore, the non-pharmacological treatment modalities “… should include education, exercise, applicances and weight reduction.” The evidence supporting the use of these nonpharmacologic modalities will be reviewed in this chapter.

Patient Education

Education is important for all people with OA; for many, it is the most important intervention. Pain and disability, the two greatest concerns of patients with OA, are concerns that should be addressed by educational programs for the patient. The literature suggests that education of the patient with OA can increase the practice of healthy behaviors, improve health status, and decrease health care utilization. Lorig and colleagues carried out a series of studies on the Arthritis Self-Management ProgramTM that is taught in the community by teams of trained lay leaders who conduct 2-hour weekly group sessions with 10 to 15 people.10,11,12,13 Study participants increased their level of physical activity, increased their use of cognitive pain management techniques, and reported decreased pain. Reinforcement after 1 year did not add to the effect, and subjects who were observed for up to 4 years continued to demonstrate reduced pain; they also had fewer arthritis-related visits to physicians. The Arthritis Self-Management ProgramTM is now sponsored by the Arthritis Foundation, a national voluntary arthritis organization with chapters throughout the United States, and modifications are used throughout the world.

Despite the widespread recommendation that education be part of the basic program for management of patients with symptomatic OA, the supporting evidence suggests only a weak effect of education on pain and functional limitation.14,15 Superio-Cabuslay and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of controlled trials of patient education interventions in OA and rheumatoid arthritis and compared the effects on pain and functional disability to effects obtained in a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).14

They identified 23 patient education trials, 19 of which met their inclusion criteria; 10 of these trials included patients with OA, either exclusively or predominantly. Sample size in these 10 OA trials ranged from 85 to 707 and the median duration of the trials was 16 weeks. The weighted average effect size for reduction in pain in the OA trials was 0.15 (95% confidence interval [CI] -0.43, 0.73) and for reduction in physical disability, -0.02 (95% CI -0.51, 0.47); neither of these changes was statistically significant.

They identified 23 patient education trials, 19 of which met their inclusion criteria; 10 of these trials included patients with OA, either exclusively or predominantly. Sample size in these 10 OA trials ranged from 85 to 707 and the median duration of the trials was 16 weeks. The weighted average effect size for reduction in pain in the OA trials was 0.15 (95% confidence interval [CI] -0.43, 0.73) and for reduction in physical disability, -0.02 (95% CI -0.51, 0.47); neither of these changes was statistically significant.

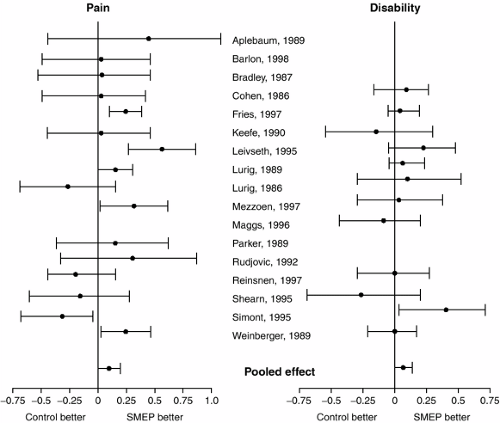

A more recent meta-analysis by Warsi and colleagues produced similar results.15 These authors identified 35 controlled trials of which 17 met their inclusion criteria; 9 of these trials included patients with OA. Of the 16 trials that reported pain outcomes, the pooled effect size was 0.12 (95% CI 0.00, 0.24); of the 12 trials that reported disability outcomes, the pooled effect size was 0.07 (95% CI 0.00, 0.15) (Fig. 14 -1). The authors noted significant heterogeneity among the trials for effects on pain but not for effects on disability. In a preplanned subgroup analysis of trials that used the Arthritis Self-Help CourseTM, there was no evidence of statistically significant efficacy for either pain or disability. These authors did not present results for studies of patients with OA separately. Based on the results of these two meta-analyses, the effects of patient education on pain and functional limitation are small at best. Beneficial effects of patient education on helplessness and coping skills may be present, however, without significant measurable effects on pain. Nonetheless, patient education has now become the standard of care and was incorporated as part of the usual care control treatment group in two large randomized trials of other nonpharmacologic interventions.16,17

Figure 14-1 Estimated effect size of education on arthritis pain and disability and 95 percent confidence intervals for individual studies included in meta-analysis by Warsi and colleagues.15 SMEP = self management education program. |

Weight Loss

Being overweight is the single most important potentially modifiable risk factor for the development of lower limb OA.18 Furthermore, in epidemiological studies, weight loss was associated with a reduced risk of symptomatic knee OA.19 Unfortunately, until recently, the evidence supporting the recommendation of weight loss for overweight patients with lower limb OA was based on nonrandomized studies that demonstrated improvement in knee pain in overweight patients with knee OA.20,21,22 A pilot randomized study of exercise plus diet compared to exercise alone in only 24 patients with symptomatic knee OA showed significantly greater weight loss in the exercise plus diet group but significant improvement in both pain and function in both groups over 24 weeks; however, the study was not powered to demonstrate differences in symptomatic improvement between the groups.23 Based on these preliminary data, Messier and colleagues subsequently conducted a definitive study of exercise plus diet in overweight patients with symptomatic knee OA.24

The Arthritis, Diet and Activity Promotion Trial (ADAPT) was a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial designed to compare the effects of exercise, dietary weight loss, and the combination compared to usual care in sedentary patients with symptomatic knee OA aged 60 and above with body mass index of 28 kg/m2 or greater.24 A total of 316 subjects with a mean age of 69 years and a mean body mass index of 34 kg/m2 were enrolled. Patients randomized to the weight loss only group lost an average of 4.9% of body weight during the 18-month intervention and had a significant 18% improvement in physical

function and a significant 15% improvement in pain as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function and pain subscales, respectively. These improvements in physical function and pain, however, were not significantly different from those seen in the usual care control group. Indeed, the only group that showed significant improvement compared to the usual care control group was the group randomized to both exercise and diet. These findings led the authors to conclude that the combination of weight loss plus moderate exercise provides better overall improvement in both symptoms and function compared with usual care. This study had several limitations including the enrollment of patients who were not only overweight but obese and very obese, the achieved weight loss was only modest leaving patients still obese on average at the end of the study, and the adherence rate in the groups randomized to either diet alone or diet plus exercise was less than 75%.25 Nonetheless, these results support the recommendations of weight loss, in the setting of exercise plus dietary counseling, for overweight patients with symptomatic knee OA.

function and a significant 15% improvement in pain as measured by the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) physical function and pain subscales, respectively. These improvements in physical function and pain, however, were not significantly different from those seen in the usual care control group. Indeed, the only group that showed significant improvement compared to the usual care control group was the group randomized to both exercise and diet. These findings led the authors to conclude that the combination of weight loss plus moderate exercise provides better overall improvement in both symptoms and function compared with usual care. This study had several limitations including the enrollment of patients who were not only overweight but obese and very obese, the achieved weight loss was only modest leaving patients still obese on average at the end of the study, and the adherence rate in the groups randomized to either diet alone or diet plus exercise was less than 75%.25 Nonetheless, these results support the recommendations of weight loss, in the setting of exercise plus dietary counseling, for overweight patients with symptomatic knee OA.

Physical Therapy Interventions

It is generally accepted that a therapeutic exercise program can improve functional capability and provide an analgesic effect in OA patients without exacerbating their symptoms.26 The general sentiment that therapeutic exercise is beneficial in OA patients is supported by a meta-analysis.27 Furthermore, a consensus panel agreed that prescription of both general (aerobic fitness training) and local (strengthening) exercises is an essential core aspect of management of every patient with hip or knee OA.28 The panel also published the statement that there are few contraindications to the prescription of strengthening or aerobic exercise in these patients. With varying degrees of scientific evidence, other consensus recommendations related to therapeutic exercises in hip and knee OA patients include the following: 1) exercise therapy should be individualized and patient-centered so as to take into account factors such as age, comorbidity, and overall mobility; 2) to be effective, exercise programs should include advice and education to promote a positive lifestyle change with an increase in physical activity; 3) group exercise and home exercise are equally effective and patient preference should be considered; 4) adherence is the principle predictor of long-term outcome from exercise; 5) strategies to improve and maintain adherence should be adopted; and 6) improvements in muscle strength and proprioception gained from exercise programs may reduce OA progression. The American College of Rheumatology recommends that patients with symptomatic lower limb OA be enrolled in a physical therapy program including aerobic and strengthening exercises.4,5,6 It should be noted, however, that it is still unclear as to whether a therapeutic exercise program is better delivered in a center-based setting or a home-based setting as a meta-analysis on this topic did not find any studies that specifically compared these approaches in OA.29

Although an exact physical therapy “formula” for OA patients has not been developed, a general rehabilitation medicine teaching principle is that a physical therapy program should consist of at least several components (Table 14-1).30,31,32,33 Patients are usually enrolled in an initial 4-week course of physical therapy on a two-to-three times a week basis. Ideally, the practitioner should perform an assessment after 1 month at which time the physical therapy summary progress note is available for the physician’s review. The physician then can make an informed decision regarding the necessity for additional physical therapy and can make modifications in the physical therapy orders as needed. Depending on how the patient progresses with this initial therapy course and upon insurance coverage eligibility, an additional month or two can then be prescribed prior to the patient being discharged to a home exercise program.

The ideal exercise intensity within the physical therapy program is unclear. For aerobic exercise, one study of 39 knee OA patients found that both high intensity and low intensity aerobic exercise was equally effective in improving a patient’s functional status, gait, pain, and aerobic capacity.34 Another study found that a 6-week high-intensity exercise program had no effect on pain or function in middle-aged patients with moderate to severe radiographic knee OA. However, some benefit resulted in improved quality of life in the exercise group compared to the control group.35

TABLE 14-1 TYPICAL PHYSICAL THERAPY PROGRAM CONTENT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Specific Modalities

Typical modalities administered alone or in combination to OA patients by physical therapists include thermotherapy (the therapeutic use of heat), cryotherapy (the therapeutic use of cold), and electrical stimulation. Although it is still unclear as to how to optimally use each of these modalities, some basic principles exist; for example, it has traditionally been taught that cold is more likely than heat to be beneficial in acute arthritic flares characterized by pain and swelling. The basis behind this principle is that cold-induced vasoconstriction helps to limit tissue edema formation and has an anti-inflammatory effect presumably by lowering joint temperature, collagenase activity, and white blood cell counts within arthritic joints.36 Although a review of the effects of locally applied heat or cold on the deeper tissues of joints and on joint temperature

in patients did not find consistent results, locally applied heat generally increases and locally applied cold generally decreases the temperature of the skin, superficial and deeper tissues, and joint cavity.37

in patients did not find consistent results, locally applied heat generally increases and locally applied cold generally decreases the temperature of the skin, superficial and deeper tissues, and joint cavity.37

However, actual studies comparing the clinical effects of these thermal modalities in OA patients have largely been lacking. A Cochrane systematic review examined randomized controlled trials on participants with clinical and/or radiological confirmation of OA of the knee and interventions using heat or cold therapy compared with standard treatment or placebo.38 Three randomized controlled trials involving 179 patients were identified. Ice massage had a statistically significant beneficial effect on range of motion, function, and knee strength compared to control. While cold packs decreased swelling, hot packs had no beneficial effect on edema compared with placebo or cold application. However, ice packs did not affect pain significantly compared to control. The authors concluded that more well-designed studies with a standardized protocol and adequate numbers of subjects are needed to evaluate the effect of thermotherapy in the treatment of knee OA.

Heat is used in OA patients in order to enhance stretching exercises by increasing tissue elasticity and in order to provide analgesia.39 The purported heat-induced analgesia is believed to occur via direct suppression of free nerve endings, via vasodilatation-enhanced removal of metabolic byproducts, and by the suppression of skeletal muscle hyperactivity through activation of descending pain-inhibitory systems by unknown mechanisms.40 Heating modalities can be classified into those that heat superficially, and those that heat deeply. Superficial heat can be further subclassified into conduction (the direct transfer of thermal energy between two objects that are in physical contact with one another, such as occurs with a water bottle), convection (the exchange of heat by movement of the current the molecules in the air or liquid across the body’s surface, such as occurs in a heated whirlpool), or radiation (the transfers of heat by the absorption of electromagnetic energy, such as occurs with an infrared lamp).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree