Autoimmune and Inflammatory Ophthalmic Diseases

Sergio Schwartzman

C. Michael Samson

Scott S. Weissman

There are multiple autoimmune diseases that can affect the eye with different implications. These can include idiopathic illnesses or the association of ophthalmic diseases with systemic autoimmune illnesses.

The systemic therapy for autoimmune ophthalmic illnesses frequently overlaps that used in systemic autoimmune illnesses.

It is important to exclude infectious and malignant (lymphoma) diseases when treating autoimmune eye diseases.

Close communication needs to be maintained between the ophthalmologist and the rheumatologist treating patients with autoimmune eye diseases.

Autoimmune ophthalmic diseases comprise a heterogeneous group of illnesses that have different etiologies, clinical presentations, laboratory findings, and responses to therapy.

The eye and its associated orbital structures may exhibit pathologic changes in patients afflicted with many systemic autoimmune illnesses. In certain inflammatory joint diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), there is a similarity in the pathologic processes occurring in the joints and in the eye. Inflammation in the conjunctiva and sclera seems to be somewhat analogous to that occurring in the synovium and cartilage, where uncontrolled and relentless immunologically mediated inflammation in either organ results in its destruction.

Rheumatic illnesses in which ophthalmic involvement is most common are the human leucocyte antigen-B27 (HLA-B27) associated diseases, RA, Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), Behçet’s disease, and sarcoidosis.

For the purposes of classifying the ocular manifestations of connective tissue diseases (CTDs), it is convenient to conceptualize the eye anatomically as a structure consisting of three concentric spheres or coats: an outer collagen coat or scleral shell; a middle vascular coat, known as the uveal tract; and the inner coat or retinal layer. Each of the various CTDs shows a characteristic pattern involving one or more of these structures.

The outer collagen or corneoscleral layer becomes involved with RA, and a scleritis results.

The middle or uveal coat is more often involved with the spondyloarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylitis (AS) or the oligoarticular juvenile arthritis, and iridocyclitis develops.

The inner, retinal layer is involved in SLE, so that a characteristic retinal vasculitis, retinopathy, or choroidopathy results.

The etiologies of idiopathic uveitis, scleritis, and ophthalmic vasculitis are largely unknown. In all probability, the causes of these diseases differ and the findings of uveitis, scleritis, and vasculitis represent multiple disease processes. The ophthalmic manifestations of systemic autoimmune diseases are probably the consequence of the same mechanism that is responsible for the underlying systemic illness. It is, however, problematic to explain why all the patients with a given systemic illness do not develop ophthalmic involvement. This may be due to the requirement for a particular genetic profile and/or due to the need for specific exogenous exposures.

When evaluating patients with autoimmune ophthalmic diseases, it is critical to exclude infectious and malignant conditions that can affect the eye. These may span multiple etiologies including syphilis, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, rickettsia, viral infections, toxoplasmosis, histoplasmosis, and toxocariasis. Lymphoma may initially present as a form of uveitis.

It is critical that every patient with a rheumatic illness who develops ophthalmic involvement be evaluated by an ophthalmologist, preferably one who has had experience with autoimmune illnesses, and a rheumatologist. Close communication should exist between these specialists in caring for patients with autoimmune diseases of the eye.

The workup for autoimmune ophthalmic illnesses should be based primarily on the complete history and physical examination because the underlying illnesses dramatically vary. Although “laboratory screens” exist, we feel that the diagnostic workup of patients with autoimmune eye disease should be individualized and targeted. It is critical, however, to ensure that infectious and malignant illnesses be excluded. All patients who have inflammatory disease of the eye should have a full history and physical examination.

In patients with uveitis, one needs to define the specific anatomic involvement of the uveal tract (ophthalmoscopy) and chronicity.

I. ANATOMY

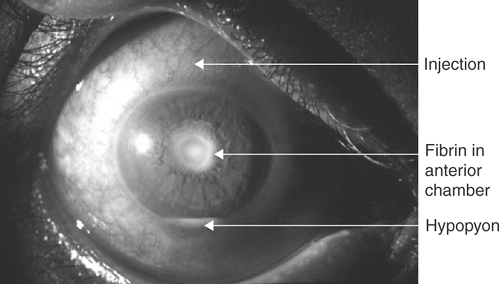

Anterior uveitis. Involvement of the iris and/or the ciliary body with cells in the aqueous humor of the anterior chamber (Fig. 18-1).

Intermediate uveitis. Inflammation in the vitreous cavity.

Posterior uveitis. Choroid, retinal involvement, and/or optic neuritis.

Panuveitis. Involvement of anterior and posterior segments.

II. CHRONICITY

Acute uveitis. Less than 3 months.

Chronic uveitis. Greater than 3 months.

III. SYMPTOMS AND OPHTHALMIC FINDINGS

Anterior uveitis. Acute—pain, photophobia, and red eye. Ophthalmoscopy reveals cells in the anterior chamber. Chronic—similar to acute symptoms although less pronounced, however, with decreased visual acuity. Ophthalmoscopy may demonstrate anterior chamber cells, synechiae, band keratopathy, glaucoma, and cataract.

Intermediate uveitis. Decreased visual acuity and floaters. Cells in the vitreous and “snowbanking” may be noted on ophthalmoscopy in cases of “pars planitis.” Note the association of intermediate uveitis with multiple sclerosis.

Posterior uveitis. Decreased visual acuity and floaters, occasionally pain and photophobia. Ophthalmoscopy reveals cells in the vitreous, choroid, and retinal infiltrates, and vascular involvement.

IV. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Anterior uveitis

HLA-B27 associated uveitis.

AS.

Reactive arthritis (ReA).

Psoriatic arthropathy.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Whipple’s disease.

Sarcoidosis.

Behçet’s disease.

Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis.

JIA.

Syphilis.

Lyme disease.

Tuberculosis.

Herpes simplex virus.

Herpes zoster virus.

Other infectious causes.

Postsurgical uveitis.

Tubular interstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome.

Intermediate uveitis

Sarcoidosis.

Syphilis.

Lyme disease.

Multiple sclerosis.

Inflammatory bowel disease.

Posterior uveitis

V. THERAPY

Anterior uveitis. Cycloplegic agents and topical steroids (e.g., prednisolone acetate 1% every 1 to 6 hours depending on severity). If disease is resistant, periocular steroids injections, systemic steroids (e.g., prednisone 1 mg/kg), or immunosuppressive agents (e.g., cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate) can be used. Anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy has been demonstrated to be of benefit in patients who have uveitis resistant to immunosuppressive medications (although not approved for this indication). It is of interest that although the anti-TNF agents target the same cytokine, there appears to be a clear superiority of infliximab over etanercept.

Posterior uveitis and panuveitis. These illnesses tend to be resistant to therapy with topical corticosteroids and frequently require therapy with systemic steroids and immunosuppressive agents. Biological anti-TNF therapies may have their greatest benefit in this group of patients. Intravitreal sustained drug delivery systems that are either biodegradable or nonbiodegradable have also been employed.

I. SYMPTOMS AND OPHTHALMIC FINDINGS

Severe eye pain is the most common complaint, with visual loss and photophobia also occurring. Inflammation of the scleral, episcleral, and conjunctival vessels occurs, resulting in a red, inflamed eye (Fig. 18-2). Particularly in chronic scleritis, the sclera may become thin with a consequent bluish appearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree