Arthroscopy of the Subdeltoid Space and Biceps Tendon Transfer

Samuel A. Taylor

Moira M. McCarthy

Ashley M. Newman

Stephen J. O’Brien

INDICATIONS

The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) is an underappreciated pain generator in the shoulder leading to an underdiagnosis of related pathology. Transfer to the conjoint tendon is an option for surgical management of biceps-labrum complex-related pathology and has been very successful in alleviating pain and mechanical symptoms while preserving cosmesis (preventing a Popeye sign) and limiting fatigue and discomfort (Fig. 16-1). Subdeltoid arthroscopy was developed to facilitate this procedure, and as an exposure technique, it offers great promise for the treatment of other shoulder pathologies.

Traditional open procedures are increasingly being replaced by less invasive arthroscopic techniques. Arthroscopy offers many advantages over open surgery, including reduced blood loss, operative time, postoperative pain and scar formation, and hospital stay. Arthroscopic techniques have evolved and are currently the treatment of choice for many shoulder pathologies including, among others, anterior instability, rotator cuff tears, impingement, and biceps-labrum complex lesions. Despite these advances, open surgery remains the gold standard for some procedures due in large part to the limitations of arthroscopy to reproduce comparable visualization and manipulation of requisite anatomic structures. The inadequacy of current standard arthroscopic techniques can lead to increased operative time, the potential for an insufficient surgical repair, or a conversion to open surgery to accomplish successful treatment.

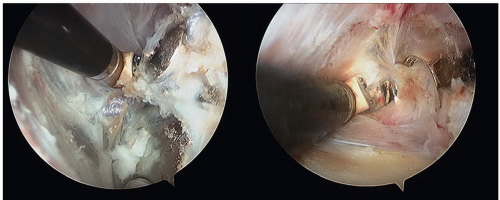

The arthroscopic “Subdeltoid Approach,” as described by the senior author (SJO), is a technique that provides unparalleled visualization and functional access to the extracompartmental space of the anterior shoulder, especially as it relates to the biceps-labrum complex (1, 2, 3). Originally described to facilitate the surgical management of disorders of the LHBT including LHBT transfer to the conjoint tendon, the subdeltoid arthroscopic technique can be applied to a multitude of anterior shoulder pathologies. This technique has already been used to address complex shoulder instability, pectoralis major tears, subscapularis tears, massive rotator cuff tears, and removal of proximal humerus plates (Fig. 16-2).

The LHBT has been implicated as a source of shoulder pain, but the diagnosis and treatment remain controversial. The LHBT is innervated by a network of sensory nerve fibers (4), indicating its role in shoulder pain. The function of the LHBT is controversial as well with many authors suggesting it represents a vestigial structure of limited clinical significance (2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). Several treatment options are available for LHBT pathology including tenotomy, tenodesis, and transfer. Simple tenotomy has been advocated by several authors (5, 17, 18, 19) verified by the pain relief reported with spontaneous rupture of the LHBT (19, 20, 21, 22). Kelly et al. (18) reported pain relief in 95% of patients undergoing a tenotomy with or without concomitant procedures. However, particularly in younger patients, there is a high incidence of complications including fatigue discomfort and

cosmetic deformity (Popeye sign) (5, 17, 18, 19). Traditional tenodesis techniques range from open bony tenodesis to arthroscopic soft-tissue tenodesis. Various techniques have been described for bony fixation including bone tunnels, bone anchors, staples, and interference screws. These, however, have been described but result in high levels of postoperative pain at the tenodesis site (6% to 40%) (6, 7, 17, 18, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30). Prior to the development of subdeltoid arthroscopy and arthroscopic transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon, soft-tissue transfer of the LHBT using an open weave technique (31) and bony tenodesis to the coracoid (25) were previously described but not widely accepted.

cosmetic deformity (Popeye sign) (5, 17, 18, 19). Traditional tenodesis techniques range from open bony tenodesis to arthroscopic soft-tissue tenodesis. Various techniques have been described for bony fixation including bone tunnels, bone anchors, staples, and interference screws. These, however, have been described but result in high levels of postoperative pain at the tenodesis site (6% to 40%) (6, 7, 17, 18, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30). Prior to the development of subdeltoid arthroscopy and arthroscopic transfer of the LHBT to the conjoint tendon, soft-tissue transfer of the LHBT using an open weave technique (31) and bony tenodesis to the coracoid (25) were previously described but not widely accepted.

LHBT symptoms are often persistent and debilitating for patients despite conservative measures. In spite of advances in imaging techniques such as MRI and ultrasound, the diagnosis of biceps-labrum complex lesions remains largely clinical and is not infrequently misdiagnosed. The following has proven to be a useful diagnostic algorithm.

Patients with biceps-labrum complex lesions traditionally present with anterior shoulder pain. Our clinical experience, however, has demonstrated wide variability in symptomatology, ranging from anterior to posterior pain, from a sensation of tightness to a sense of instability, or even with mechanical symptoms. Acute trauma may steer the clinician in the direction of groove instability secondary to subscapularis tear or a superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesion. Insidious onset of pain is usually related to a chronic process involving the tendon itself.

A thorough physical examination is paramount, keeping in mind a broad differential diagnosis including acromioclavicular (AC) pathology, rotator cuff disease, subacromial bursitis, glenohumeral synovitis, adhesive capsulitis, impingement, instability, and processes more proximal, such as cervical spine pathology. Inspection of the shoulder for atrophy may elucidate chronicity, and muscular asymmetry (Popeye sign) may indicate spontaneous rupture of the LHBT. A motor assessment including cuff strength should be assessed. Point tenderness to palpation in the bicipital groove is often present in the setting of biceps lesions.

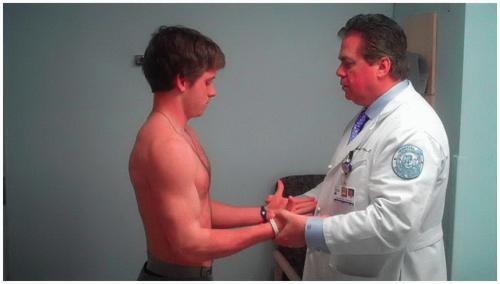

Several provocative tests of LHBT pathology have been described. Most notable, and able to be elicited on physical exam, are Speed, Yergason, and O’Brien tests. The Yergason test is performed with the patient’s arm

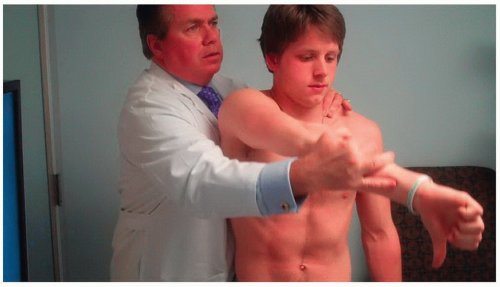

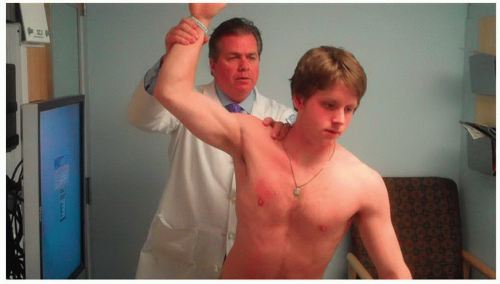

in the neutral position and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees (Fig. 16-3). The physician then grasps the wrist and resists the patient’s attempt to supinate and flex the elbow. A positive test results in pain and discomfort and has been implicated to indicate a defect in the transverse humeral ligament such that the LHBT is not maintained within the bicipital groove. While this test has a low sensitivity (9%), it is very specific (93%) for tendonitis of the LHBT (32). Further testing has demonstrated overlap of the Yergason test for detecting SLAP lesions with 43% sensitivity and 79% specificity (33). The Speed’s test is performed by having the patient elevate his extended, supinated arm against resistance (Fig. 16-4). Anterior shoulder pain during this maneuver is reported to have a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 13.8% for biceps tendinopathy (34). The Speed’s test was later found to be 32% sensitive and 75% specific for SLAP tears (33). The active compression test (Fig. 16-5) was introduced in 1998 (35) as a method of assessing patients for SLAP lesions. With the patient’s arm flexed at 90 degrees, adducted 10 to 15 degrees, and internally rotated such that the thumb points inferiorly, the physician applies downward force while the patient resists. The maneuver is repeated with the wrist supinated such that the palm is upward facing. If pain is present “inside the shoulder” with the thumb pointed down and is eliminated or reduced with the palm facing upward, a positive test results. This test was shown to have a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 98.5% for SLAP lesions.

in the neutral position and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees (Fig. 16-3). The physician then grasps the wrist and resists the patient’s attempt to supinate and flex the elbow. A positive test results in pain and discomfort and has been implicated to indicate a defect in the transverse humeral ligament such that the LHBT is not maintained within the bicipital groove. While this test has a low sensitivity (9%), it is very specific (93%) for tendonitis of the LHBT (32). Further testing has demonstrated overlap of the Yergason test for detecting SLAP lesions with 43% sensitivity and 79% specificity (33). The Speed’s test is performed by having the patient elevate his extended, supinated arm against resistance (Fig. 16-4). Anterior shoulder pain during this maneuver is reported to have a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 13.8% for biceps tendinopathy (34). The Speed’s test was later found to be 32% sensitive and 75% specific for SLAP tears (33). The active compression test (Fig. 16-5) was introduced in 1998 (35) as a method of assessing patients for SLAP lesions. With the patient’s arm flexed at 90 degrees, adducted 10 to 15 degrees, and internally rotated such that the thumb points inferiorly, the physician applies downward force while the patient resists. The maneuver is repeated with the wrist supinated such that the palm is upward facing. If pain is present “inside the shoulder” with the thumb pointed down and is eliminated or reduced with the palm facing upward, a positive test results. This test was shown to have a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 98.5% for SLAP lesions.

FIGURE 16-2 The versatile subdeltoid space is used to remove a proximal humerus plate arthroscopically. |

FIGURE 16-4 The Speed test. The patient elevates extended arms with the palm up, while the physician resists. Pain at the bicipital groove suggests biceps-related pathology. |

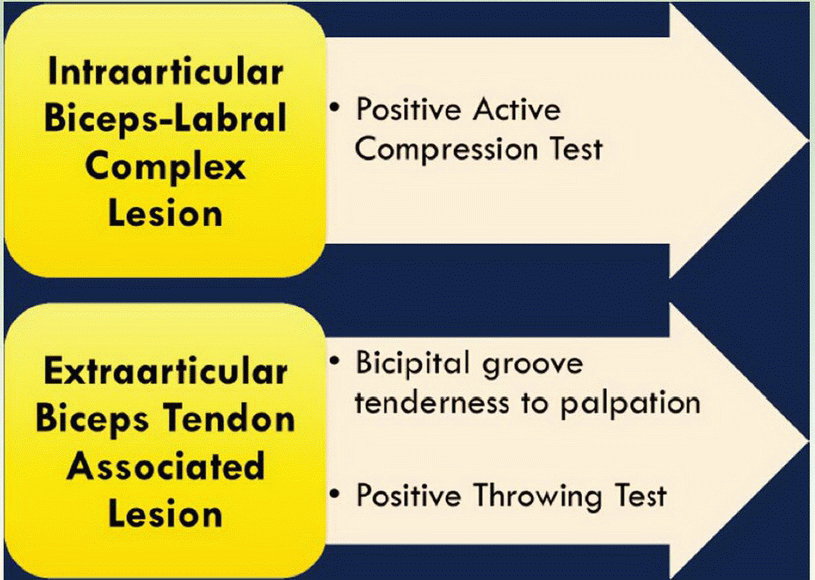

The senior author has built upon this foundation and proposed a clinical diagnostic examination called “The 3-Pack.” This is actually a series of three findings (a) tenderness to palpation in the bicipital groove, (b) positive active compression test, and (c) positive “throwing test.” During direct palpation of the groove, the patient is asked, “Is this your pain?” and findings are always compared to the contralateral side. The active compression test is performed as noted above, asking the same question, “Is this your pain?” The throwing test (Fig. 16-6) is performed with the patient’s involved arm elevated and maximally externally rotated as if to throw a

ball overhand. As the patient steps forward with his contralateral leg, the examiner resists the forward motion of the arm. A positive result is indicated by reproduction of the patient’s pain. Positive groove tenderness and throwing test are indicative of “extra-articular” biceps lesions, while the active compression test points to intraarticular pathology (Table 16-1). A prospective validation study is ongoing, and preliminary results suggest a stronger correlation of physical examination than MRI findings and arthroscopic findings.

ball overhand. As the patient steps forward with his contralateral leg, the examiner resists the forward motion of the arm. A positive result is indicated by reproduction of the patient’s pain. Positive groove tenderness and throwing test are indicative of “extra-articular” biceps lesions, while the active compression test points to intraarticular pathology (Table 16-1). A prospective validation study is ongoing, and preliminary results suggest a stronger correlation of physical examination than MRI findings and arthroscopic findings.

TABLE 16-1 Three-pack Examination Includes the Active Compression Test, Tenderness to Palpation in the Bicipital Groove, and the Throwers Test | ||

|---|---|---|

|

When a biceps lesion is suspected, a course of conservative measures including physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and corticosteroid injections should be considered and can provide some degree of relief and even resolution of symptoms in a portion of patients (36, 37). Some patients will, however, require surgical intervention. Indications for surgery—tenotomy, tenodesis, or transfer—vary among authors. Sethi et al. (38) suggested that partial-thickness tears (>25%), chronic atrophic tendinopathy, and bicipital groove instability are indications for tenotomy or tenodesis. They also noted that relative indications for surgery included failed decompression for a concomitant pathology. We feel, however, that biceps tendinopathy pain is often irreversible without surgical intervention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree