Arthroscopic Treatment of Subacromial Impingement

Gregory A. Tayrose

Spero G. Karas

DEFINITION

Impingement syndrome was originally described by Neer20 in 1972 as a chronic impingement of the rotator cuff beneath the coracoacromial arch resulting in shoulder pain, weakness, and dysfunction.

Repetitive microtrauma of the supraspinatus tendon’s hypovascular area causes progressive inflammation and degeneration of the tendon, resulting in bursitis, tendinopathy, and rotator cuff tear.

Extrinsic compression of the rotator cuff may occur against the undersurface of the anterior third of the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, or the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

ANATOMY

The scapula is a thin sheet of bone from which the coracoid, acromion, spine, and glenoid processes arise.

The acromion, together with the coracoid process and the coracoacromial ligament, form the coracoacromial arch. The arch is a rigid structure through which the rotator cuff tendons, subacromial bursa, and humeral head must pass.

The supraspinatus tendon is confined above by the subacromial bursa and the coracoacromial arch and below by the humeral head in an area referred to as the supraspinatus outlet. There is an average of 9 to 10 mm of space between the acromion and humerus in the supraspinatus outlet.11 This space is narrowed by abnormalities of the coracoacromial arch. Internal rotation or forward flexion of the arm also decreases the distance between the coracoacromial arch and the humeral head.

The subacromial and subdeltoid bursa overlie the supraspinatus and the humeral head. These bursae serve to cushion and lubricate the interface between the rotator cuff and the overlying acromion and AC joint. The bursa may become thick and fibrotic in response to progressive inflammation, further decreasing the volume of the subacromial space.

The supraspinatus tendon has a watershed area of hypovascularity located 1 cm medial to the insertion of the rotator cuff. This area may predispose the supraspinatus tendon to degeneration, tendinopathy, and tears from overuse, repetitive microtrauma, or outlet impingement.

PATHOGENESIS

Extrinsic or outlet impingement of the rotator cuff is caused by abnormalities of the coracoacromial arch, resulting in an overall decreased area for the rotator cuff tendons within the supraspinatus outlet.

Extrinsic or outlet impingement should be differentiated from internal impingement, which stems from contact of the articular side of the supraspinatus on the posterosuperior glenoid rim in throwing athletes during the late cocking phase of throwing.

Alternatively, intrinsic degeneration of the rotator cuff may lead to dysfunction of the cuff’s native glenohumeral stabilization mechanism. These pathomechanics result in elevation of the humeral head relative to the acromion and subsequent outlet impingement.

Acromial morphology most commonly accounts for narrowing of the supraspinatus outlet.

Bigliani et al4 described three types of acromial morphology: the type I acromion is flat, type II is curved, and type III is hooked. They noted that 70% of cadaver shoulders with rotator cuff tears had a type III acromion.

A type I acromion with an increased angle of anterior inclination may cause impingement of the rotator cuff by narrowing the supraspinatus outlet.

In a study of cadaveric scapulae, Neer20 observed a characteristic ridge of proliferative spurs and excrescences on the undersurface of the anterior acromion overlying areas with evidence of rotator cuff impingement.

Other processes that narrow the supraspinatus outlet include osteophytes of the AC joint; hypertrophy of the coracoacromial ligament; malunion of the greater tuberosity, clavicle, or acromion; inflammatory bursitis; calcific rotator cuff tendinitis; a flap from a bursal-sided rotator cuff tear; or an unstable os acromiale.

Os acromiale is a failure of fusion in one of the acromial ossification centers.

Ossification centers are preacromion, mesoacromion, metaacromion, and basiacromion.

Nomenclature is based on the segment anterior to the nonunion.

Ununited mesoacromion is the most common type.22

In an osteologic survey of the city of Cleveland’s unclaimed dead, Sammarco28 noted that os acromiale is more common in African Americans than Caucasians (13.2 % vs. 5.8 %) and more common in men than women (8.5% vs. 4.9%).

Excessive motion at the nonunion site predisposes to outlet impingement.

NATURAL HISTORY

Neer21 classified impingement into three progressive stages:

Stage I impingement lesions occur initially with excessive overhead use in sports or work. A reversible process of edema and hemorrhage is found in the subacromial bursa and rotator cuff. This typically occurs in patients younger than 25 years old.

With repeated episodes of mechanical impingement and inflammation, stage II lesions develop. The bursa may become irreversibly fibrotic and thickened, and tendinitis

develops in the supraspinatus tendon. Classically, this lesion is found in patients 25 to 40 years of age.

As impingement progresses, stage III lesions may occur, with partial or complete tears of the rotator cuff. Biceps lesions and alterations in bone at the anterior acromion and greater tuberosity may also develop. These lesions are found almost exclusively in patients older than 40 years.

Stage I and II lesions typically respond to nonoperative modalities if the offending activity is limited for a sufficient amount of time.

Refractory stage II lesions and stage III lesions require operative intervention.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with impingement syndrome typically complain of the insidious onset of shoulder pain that primarily occurs with overhead activities. Pain is typically localized to the lateral aspect of the acromion, extending distally into the deltoid.

Patients may experience pain at night, especially when lying on the affected side.

Typically, patients with impingement syndrome do not complain of diminished shoulder motion.

Physical examination methods to identify subacromial impingement include

Palpation of the point of Codman just anterior to the anterolateral corner of the acromion: Tenderness is frequently a sign of supraspinatus tendinitis, tendinopathy, or acute tear of supraspinatus tendon.

Range of motion: Patients with impingement may have limited internal rotation from posterior capsule contracture. Active motion is typically more painful than passive motion, especially in the descending, eccentric phase of the motion arc.

Painful abduction arc: Pain from 60 to 120 degrees (maximally at 90) suggests impingement. Patients may externally rotate at 90 degrees to clear the greater tuberosity from the acromion and increase motion.

Neer impingement sign: This maneuver compresses the critical area of the supraspinatus tendon against the anterior -inferior acromion, reproducing impingement pain.

Hawkins sign: This maneuver compresses the supraspinatus tendon against the coracoacromial ligament, reproducing the pain of impingement. It has high sensitivity but low specificity.

Impingement test: The injection of local anesthetic into the subacromial space followed by relief of pain on clinical exam. This test has greatly improved specificity for making the diagnosis of subacromial impingement. A positive test is also positively prognostic of a satisfactory outcome after subacromial decompression.14

A complete physical examination of the shoulder should be performed to evaluate for associated pathology or other processes in the differential diagnosis.

AC osteoarthritis: This degenerative process may be clinically asymptomatic, but an inferior AC joint osteophyte can contribute to the etiology of impingement syndrome. If symptomatic, tenderness may be elicited at the AC joint with palpation and the cross-arm adduction test.

Rotator cuff tear: The history of traumatic injury is variable. Patients complain of deep shoulder pain at night and may complain of weakness in the affected shoulder. Strength testing will evaluate for rotator cuff tear and tear size.

Glenohumeral instability: Subluxation or dislocation of the humeral head while stabilizing the scapula (load and shift test) helps confirm the diagnosis of glenohumeral instability. Throwing athletes may have a complex pattern of pathology that includes anterior laxity and posterior capsular tightness, which may result in internal impingement. These patients typically have posterior pain with apprehension testing. Internal impingement must be differentiated from extrinsic outlet impingement. Although a posterior capsule contracture can predispose patients to outlet impingement, classic extrinsic outlet impingement is believed to be rare in throwing athletes.

Biceps pathology: Pain is typically in the anterior shoulder. Tenderness may be elicited in the area of the bicipital groove. Pain during resisted flexion of the arm with the elbow in extension and the forearm supinated (Speed test) indicates biceps pathology.

Glenohumeral arthritis: Pain is associated with movement below 90 degrees of elevation. Patients complain of pain at night. Cogwheel crepitus may be present when loading the glenohumeral joint during resisted arm abduction.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard anteroposterior (AP) radiographs in internal and external rotation and a supraspinatus outlet view should be taken for the evaluation of impingement syndrome.

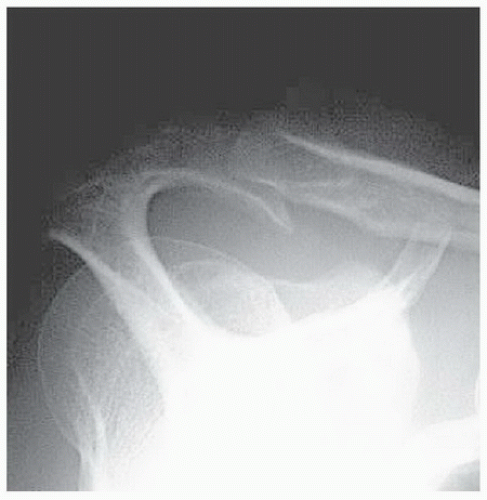

A supraspinatus or acromial outlet view is a transscapular view taken with the radiographic beam angled 15 to 20 degrees caudally (FIG 1).

The outlet view is the best plain radiographic technique to evaluate acromial morphology and aid in detection of inferiorly directed enthesophytes. With this information, the surgeon may accurately plan the amount of osseous resection required to convert the acromion to type I morphology.

Acromiohumeral distance is the minimal distance between the acromial undersurface and the humeral head. An acromiohumeral distance of less than 7 mm is considered abnormal.

An abnormal acromiohumeral distance has been shown to correlate with the clinical status of patients.18

FIG 1 • Supraspinatus outlet view. This view helps the surgeon assess acromial morphology and facilitates preoperative planning for the amount of acromial resection.

Additional views or diagnostic tests may be used to further evaluate the painful shoulder.

Axillary lateral radiographs may be helpful in the diagnosis of os acromiale.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scan, arthrography, and ultrasonography should be reserved for patients whose diagnosis of impingement syndrome is not completely clear from the history, physical examination, and radiographs. These other modalities will also help diagnose biceps, labral, and rotator cuff pathology.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Rotator cuff pathology

AC osteoarthritis

Glenohumeral instability

Posterior glenoid and rotator cuff (internal) impingement

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis

Biceps tendon pathology

Adhesive capsulitis

Cervical spine disease

Viral brachial plexopathy

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Visceral problems (eg, cholecystitis, coronary insufficiency)

Neoplasm of the proximal humerus or shoulder girdle

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

All patients with subacromial impingement syndrome should undergo a course of nonoperative management for 3 to 6 months. Treatments include subacromial steroid injection, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, hot and cold therapy, ultrasound, and physical therapy.

Most patients can be successfully treated within 3 to 6 months. Large retrospective studies show that approximately 70% of patients with impingement syndrome will respond to conservative management.19

In the short term, a graduated physiotherapy program has been shown to be as effective as arthroscopic subacromial decompression.5

The rehabilitation program should start by preventing overuse or reinjury with relative rest and activity modification.

Therapy is advanced as pain and inflammation subside and is directed at regaining full range of motion and eliminating capsular contractures. In particular, posterior capsular contracture is addressed with progressive adduction and internal rotation stretching.

As pain continues to decrease and range of motion improves, strengthening of the rotator cuff and periscapular musculature is initiated. This is achieved through progressive resistance exercises with elastic bands or free weights.

Patients should avoid overhead weight training (military press, latissimus pulldowns) and long lever arms (straight arm lateral raises) because these maneuvers can exacerbate impingement and produce undue torque on the rotator cuff and glenohumeral joint.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Operative intervention is indicated if patients continue to have symptoms of impingement syndrome that are refractory to a progressive rehabilitation program of stretching and strengthening over a minimum 3- to 6-month period.

If the diagnosis is not completely clear, a more extensive diagnostic workup is warranted before surgical intervention.

The most common cause of failure for arthroscopic subacromial decompression and anterior acromioplasty is error in diagnosis.1

Preoperative Planning

Imaging studies are reviewed to ensure the preoperative diagnosis is correct.

Particular attention should be paid to acromial morphology, the status of the AC joint, and evidence of rotator cuff pathology, as these disease processes often coexist.

The preoperative supraspinatus or acromial outlet view gives the surgeon an accurate measurement of the amount of bone that must be resected from the anterior acromion to convert the acromial morphology to type I.16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree