Arthroscopic Treatment of Internal Impingement

Daryl C. Osbahr

James R. Andrews

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

When considering arthroscopic management for internal impingement, the decision-making process is extremely complicated as differentiating adaptive and pathological changes can be difficult resulting in unclear indications and contraindications. Therefore, it is critical for the clinician to have a thorough understanding of the spectrum of internal impingement while taking into account historical, pathophysiological, and clinical management considerations.

Historical Considerations

Overhead athletes require a delicate balance of shoulder mobility and stability to allow for the repetitive functional demands required of the throwing motion. The understanding of the throwing shoulder has greatly evolved over the past several decades. However, the etiology and sequence of events that lead to the painful and dysfunctional throwing shoulder remain controversial. Bennett first described radiographic evidence of a posteroinferior glenoid exostosis in baseball players in 1941 and subsequently characterized posterior shoulder pain in the thrower in 1959 (1, 2). In 1977, Lombardo et al. (3) correlated posterior shoulder pain in overhead athletes with the late cocking phase of the throwing motion.

With the advent of arthroscopy, Andrews et al. (4) was the first to report an association between intra- articular pathology in overhead athletes, including rotator cuff tears and superior labral lesions of the biceps brachii origin, and competitive overhead athletic activities (5). Walch et al. corroborated the findings of Andrews and published a landmark paper coining the term internal impingement to describe these arthroscopic findings revealing “impingement of the deep surface of the rotator cuff on the posterosuperior border of the glenoid while the arm was placed in the position of abduction and external rotation” (5). This pathologic condition is in contradistinction to Neer’s classic description of subacromial impingement that also presents in nonoverhead athletes and involves contact between the bursal side of the rotator cuff and the coracoacromial arch (6, 7). Since proper recognition of this pathologic entity, internal impingement is now considered one of the most common forms of disability and inability to throw in overhead athletes.

Pathophysiological Considerations

Improved performance in the overhead athlete is partially reliant on adaptive changes occurring in the shoulder to produce an altered arc of motion to provide maximum velocity. In particular, baseball pitchers have been shown to produce the fastest motion of all overhead athletes with a maximum internal rotation velocity of up to 7,000 degrees per second (8, 9, 10). To this end, the throwing shoulder must improve performance through

increased external rotation in abduction at the expense of internal rotation as dictated by the total arc of motion concept demonstrated by Wilk et al. (11). The etiology for this altered arc of motion is likely multifactorial. A multitude of studies have suggested that increased glenoid retroversion (12, 13), humeral head retroversion (12, 14, 15), and anterior capsular laxity (16, 17, 18, 19) accommodate for these alterations in the throwing shoulder.

increased external rotation in abduction at the expense of internal rotation as dictated by the total arc of motion concept demonstrated by Wilk et al. (11). The etiology for this altered arc of motion is likely multifactorial. A multitude of studies have suggested that increased glenoid retroversion (12, 13), humeral head retroversion (12, 14, 15), and anterior capsular laxity (16, 17, 18, 19) accommodate for these alterations in the throwing shoulder.

Although these adaptive changes in the form of physiologic internal impingement have been demonstrated in the throwing shoulder, a sequence of events leading to pathologic internal impingement is now believed to be a primary cause of shoulder disability in the overhead athlete, particularly the baseball player. Since the original description of internal impingement by Walch et al. (5), several theories have emerged to explain the development of physiologic and pathologic internal impingement, including anterior laxity, posterior capsular contracture, and the peel-back phenomenon (16, 20, 21, 22).

Jobe’s theory of anterior microinstability noted that the normal phenomenon of internal impingement can progressively worsen in overhead throwers, as this repetitive motion results in stretching of the anterior capsuloligamentous structures (16, 17). He hypothesized that the anterior instability increases the degree of contact between the greater tuberosity, rotator cuff, and posterosuperior glenoid. This process potentially results in a constellation of findings, including pathology of the rotator cuff, glenoid bone, and glenoid labrum.

Conversely, Burkhart and Morgan theorized that the torsional superior labral anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesion rather than internal impingement is the main pathologic finding (21). They suggested that the shoulder pain is likely secondary to an acquired tight posteroinferior capsule resulting in glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD), with a posterosuperior shift in the glenohumeral contact point. This shift reduces the cam effect of the humeral head, resulting in hyperexternal rotation and increased peel-back forces of the biceps labral anchor. Based on the circle concept, the break in the labral ring associated with the SLAP lesion of the biceps anchor subsequently results in a pseudolaxity of the anteroinferior capsule on the opposite side of the circle (23).

Although these hypotheses present plausible mechanisms for the development of internal impingement, a combination of these theories may be the most plausible mechanism secondary to microinstability and overrotation. As described by Wilk et al., the throwing shoulder must improve performance by spinning back (i.e., increasing external rotation) the arc of motion through a combination of osseous and soft-tissue adaptations. Several adaptive changes, including anterior microinstability (16, 17, 18, 19), excessive external rotation, humeral head retroversion (12, 14, 15), and glenoid retroversion (12, 13), may eventually result in pathologic changes resulting in pathologic internal impingement.

Research by Meister et al. (24) supported that maximal changes in humeral head retroversion occur by the early adolescent period (12 to 13 years old). These findings have led several authors to conclude that the early, osseous adaptive changes, including humeral head and glenoid retroversion, may be protective in the early thrower. However, secondary stretching of the anterior capsule to accommodate the overrotation from osseous retroversion may lead to internal impingement over time. With or without subsequent posterior capsular contracture, this spinning back in external rotation from overrotation can also involve the “peel-back mechanism” that will additionally increase forces on the biceps-labral anchor.

Controversy still exists as to the sequence of events that lead from physiologic to pathologic internal impingement; however, most authors support that contact between the posterior rotator cuff and the glenolabral complex can be a normal phenomenon during the throwing motion (i.e., physiologic internal impingement). In fact, several cadaveric, radiographic, and arthroscopic studies have evaluated the premise of physiologic internal impingement (18, 25, 26). These studies have reinforced that internal impingement can be normal as overhead athletes can have physiologic contact between the articular surface of the rotator cuff on the posterosuperior glenoid in the asymptomatic, throwing shoulder.

Regardless of the etiology, four critical components appear necessary to develop internal impingement, including overrotation, increased glenohumeral translation, excessive horizontal extension, and GIRD. With these functional abnormalities intricately involved, the continuum of internal impingement may commence with progression from physiologic to pathologic internal impingement leading to a painful, dysfunctional throwing shoulder. These pathologic findings include partial- and full-thickness rotator cuff tears, SLAP tears, glenoid chondral lesions, anterior and posterior capsular injury, chondromalacia of the posterosuperior humeral head, and biceps lesions (3, 5, 16, 19, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37).

Clinical Considerations

The clinical evaluation of the overhead athlete with shoulder pain can be somewhat confusing and complex. Through adaptive changes, the asymptomatic throwing shoulder is distinctly different from the nonthrowing shoulder, so it is crucial for the clinician to pay close attention to differentiating pathology from normal throwing anatomy. Jobe has provided a generalized classification scheme based on clinical presentation to describe stages of internal impingement (Table 13-1); however, the surgeon must closely evaluate specific clinical history and physical examination findings to differentiate exact pathologic features prior to initiating nonoperative or operative management.

In obtaining an accurate diagnosis of internal impingement, a thorough clinical history is crucial. Internal impingement typically occurs in baseball players; however, other overhead athletes, including tennis players, can present with this pathophysiology. The clinical evaluation must begin with a standard clinical shoulder

evaluation assessing pain location, pain duration, weakness, instability, mechanical symptoms, loss of motion, and neurosensory changes. Next, the clinician must spend time obtaining a thorough throwing history, including the ability to throw or pitch, position of the arm when painful (i.e., phase of throwing motion), and associated velocity changes.

evaluation assessing pain location, pain duration, weakness, instability, mechanical symptoms, loss of motion, and neurosensory changes. Next, the clinician must spend time obtaining a thorough throwing history, including the ability to throw or pitch, position of the arm when painful (i.e., phase of throwing motion), and associated velocity changes.

TABLE 13-1 Jobe’s Clinical Classification of Internal Impingement | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

The symptomatic thrower with internal impingement will typically present with pain during the throwing motion. Localization of pain can often be vague secondary to the spectrum of pathologies involved within internal impingement. Pain will most often be localized within the posterosuperior shoulder, but anterior shoulder pain may be a feature. These athletes will also typically describe a lack of command, loss of velocity, and/ or pain during the late cocking and early acceleration phases of the overhead or throwing motion. Throwers may present with additional ill-defined symptoms, including early fatigue and difficulty “getting loose” during warm-up activities.

When assessing shoulder pain, the standard physical examination must first be performed, including inspection, palpation, range of motion, neuromuscular examination, muscular strength testing, stability tests, cervical spine exam, and special tests. In addition, the clinician must utilize the contralateral shoulder for comparison to properly interpret the entire clinical examination. As described during the clinical history, the main goal of the physical examination on the throwing athlete is to then recreate those same symptoms incurred during the throwing motion. Overhead athletes will generally present with some baseline asymmetry between the dominant and nondominant shoulder, including muscular volume, range of motion, and laxity; however, the presence of symptoms and several physical examination tests will provide valuable diagnostic information.

Overall, the thrower with internal impingement may present with excessive external rotation in the setting of decreased internal rotation (i.e., glenohumeral internal rotation deficit or GIRD), anterior shoulder instability, positive labral signs, and rotator cuff tenderness and weakness. Based upon the total motion concept by Wilk et al. (11), total shoulder motion in the bilateral shoulders should be approximately 190 degrees; however, the throwing shoulder envelope of motion will be shifted into external rotation with a resultant loss of internal rotation through adaptive changes that have occurred over time. Therefore, total motion preservation in the setting of decreased internal rotation is not itself problematic. If loss of total motion and internal rotation occur (GIRD), however, the overhead athlete may be more susceptible to injury regardless of whether it is directly related to chronic posterior capsular tightness, acute eccentric muscle activity, or the protracted and anterior tilted scapula (38, 39, 40, 41). In a clinical study involving professional baseball pitchers, in fact, there was a bilateral difference in internal rotation with the arm at 90 degrees of shoulder abduction that may result in a significant impact of shoulder injuries and subsequent surgeries (42).

Although there is an abundance of diagnostic tests involving the shoulder, we have come to rely on few special tests that are specifically targeted to the throwing athlete with special focus on pathology involving the periscapular musculature, rotator cuff, glenolabral complex, and capsular laxity. Two tests that have been especially helpful in diagnosing internal impingement are the internal impingement sign and prone posterior palpation pain (Figs. 13-1 and 13-2). In fact, Meister et al. (33) demonstrated that the internal impingement sign has 95% sensitivity and 100% specificity as confirmed by arthroscopy in diagnosing undersurface rotator cuff tears and/or posterior labral tears in overhead athletes who present with a gradual onset of posterior shoulder pain (33). Prone posterior palpation pain may be attributed to the rotator cuff, glenolabral complex, or Bennett lesion; however, the Bennett lesion (i.e., thrower’s exostosis) is typically associated with posterior pain localized more inferior than other associated pathologies. Muscular strength testing and scapular position are also vital when assessing signs of internal impingement as scapular dyskinesis and rotator cuff weakness are important when considering management options (43, 44, 45).

The glenolabral complex must then be carefully evaluated as pathologic internal impingement will typically involve SLAP pathology. We prefer tests that are provocative to the biceps-labral complex by reproducing the peel-back mechanism that occurs during the throwing motion. These tests include the resisted supination external rotation test and the biceps load test (39, 46, 47). Additional tests that may be useful but do not recreate the peel-back mechanism are the O’Brien’s test (i.e., active compression test) and the crank test (48, 49). Of the resisted supination external rotation, O’Brien’s, and crank tests, the resisted supination external rotation test

has been shown to be the most accurate in detecting SLAP lesions (50). We also prefer the clunk test that is performed in the supine position with the arm elevated 160 degrees in the scapular plane, while the humerus is axially loaded with maximal internal rotation and external rotation. A positive test is indicated when pain is elicited with or without a clunk and/or reproduction of symptoms during activity is elicited. The clinician must remember that all of these aforementioned tests typically have a high sensitivity but low specificity that accentuates the need to use caution when interpreting exam results.

has been shown to be the most accurate in detecting SLAP lesions (50). We also prefer the clunk test that is performed in the supine position with the arm elevated 160 degrees in the scapular plane, while the humerus is axially loaded with maximal internal rotation and external rotation. A positive test is indicated when pain is elicited with or without a clunk and/or reproduction of symptoms during activity is elicited. The clinician must remember that all of these aforementioned tests typically have a high sensitivity but low specificity that accentuates the need to use caution when interpreting exam results.

Although controversial, we believe that it is important to assess capsular laxity as it may represent a major factor when considering management options. As many overhead athletes will have physiologic laxity, diagnosing pathologic anterior microinstability can be extremely difficult. While evaluating capsular laxity, the

clinician should consider total motion through passive range of motion that may provide clues indicating microinstability (11). For example, asymptomatic throwing athletes should have equivalent total motion for both shoulders; however, if total motion is increased in the dominant shoulder, then the player may have some degree of laxity or microinstability that may need to be considered. In addition to total motion, the apprehension, Jobe’s relocation, and shoulder Lachman tests are also important in determining the extent of anterior laxity and microinstability in the assessment of pathologic internal impingement.

clinician should consider total motion through passive range of motion that may provide clues indicating microinstability (11). For example, asymptomatic throwing athletes should have equivalent total motion for both shoulders; however, if total motion is increased in the dominant shoulder, then the player may have some degree of laxity or microinstability that may need to be considered. In addition to total motion, the apprehension, Jobe’s relocation, and shoulder Lachman tests are also important in determining the extent of anterior laxity and microinstability in the assessment of pathologic internal impingement.

The diagnostic considerations for shoulder pain in the thrower can be extensive with overlap between diagnoses. However, pathologic internal impingement is typically manifested by posterior shoulder pain during the late cocking and early acceleration phases of the throwing motion and should be confirmed with imaging modalities. The differential diagnosis for the posterior shoulder pain indicative of pathologic internal impingement is vast and may be multifactorial. Potential pathology includes posterior rotator cuff, deltoid, teres minor and rhomboid strains, posterior capsulitis or strain, glenoid osteochondritis dissecans, Bennett lesion (i.e., thrower’s exostosis), thrower’s Hill-Sachs lesion, suprascapular nerve entrapment with and without an associated ganglion cyst, axillary nerve and quadrilateral space entrapment, long thoracic nerve injury, and isolated rotator cuff or labral injuries. Finally, the surgeons must use caution when determining shoulder pain secondary to anterior shoulder instability as this may itself cause posterior shoulder pain.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Imaging

Internal impingement should be considered a clinical diagnosis; however, clinical findings should be confirmed by imaging tests that can also provide important information for preoperative planning, when applicable. As many throwing athletes will have positive findings on imaging, this premise is especially important prior to determining the course of management. Once imaging is considered, overhead athletes should obtain a thrower’s series of conventional radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and intermittent use of computed tomography (CT).

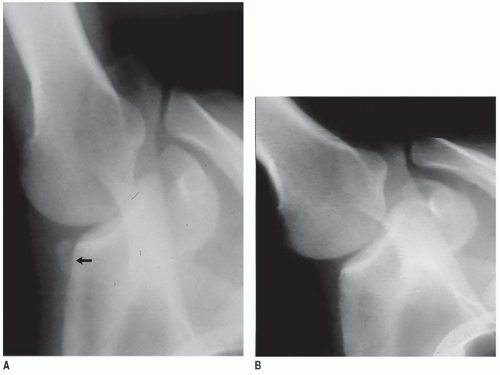

Conventional radiographs that entail the thrower’s series should include a true anteroposterior, anteroposterior, axillary, and Stryker views. In addition, axillary, scapular Y, and West Point axillary views may be selectively obtained. The base of the greater tuberosity should be evaluated on anteroposterior views, especially external rotation, as it may demonstrate sclerosis or other chronic changes that may indicate rotator cuff pathology. The Stryker view is important in identifying a Bennett lesion, an ossification on the posteroinferior glenoid rim (1, 51) (Fig. 13-3A).

FIGURE 13-3 Stryker notch view radiograph illustrating a Bennett lesion (arrow) (A) preresection and (B) postresection. |

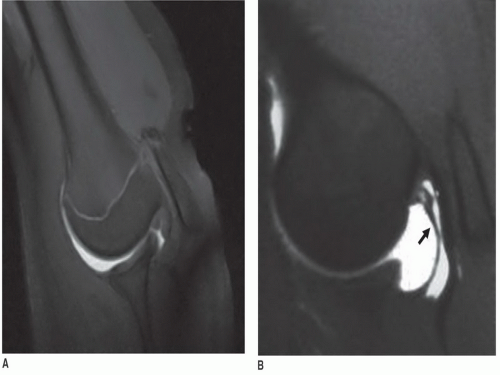

FIGURE 13-4 MRI positioned in the ABER position illustrating (A) a normal MRI with no rotator cuff tear and (B) an abnormal MRI with a delaminated, partial rotator cuff tear (arrow). |

In most throwing athletes, the diagnosis of internal impingement can be elucidated on clinical examination; however, radiographic evaluation with MRI is the workhorse in confirming the suspected pathology. If you want an excuse to operate on a throwing shoulder, in fact, then the clinician should obtain an MRI. This inherent problem for advanced imaging in these athletes relates to the high prevalence of positive findings, even in asymptomatic throwers. Therefore, the clinician should be especially careful as correlation of clinical and radiographic findings is imperative prior to proceeding with a treatment plan.

Although nonenhanced MRI has been advocated by some authors (52, 53), we prefer an MRI with gadolinium intra-articular contrast in our clinical practice. The addition of intra-articular contrast allows us to better elucidate pathology by increasing diagnostic accuracy and clarifying subtle pathology, especially when evaluating the small and partial rotator cuff tears characteristic of throwing athletes (35). In addition to the standard MRI sequences, we also advocate obtaining the ABER (abduction external rotation) view that provides functional information when diagnosing internal impingement and elucidates possible partial and delaminated rotator cuff tears (Fig. 13-4A,B).

Studies by Giaroli et al. (54) and Kaplan et al. (29) have asserted that a combination of pathology visualized on MRI can be diagnostic of internal impingement when correlating with clinical and operative assessment. These findings include articular surface supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears, posterosuperior labral pathology, and posterior humeral head cystic changes. Several other findings that should be elucidated on MRI include Bennett lesions, posterior capsular contracture at the level of the posteroinferior glenohumeral ligament, and posterior subchondral depression with associated osteophyte or cyst (i.e., thrower’s Hill-Sachs lesion) (5, 55, 56). However, MRI should be carefully correlated with clinical symptoms in throwing athletes as several studies have shown that asymptomatic baseball players can actually exhibit positive findings (26, 57, 58, 59, 60).

As most adaptive and pathologic changes characteristic of internal impingement are soft tissue in nature, including the rotator cuff, glenolabral complex, and biceps-labral anchor, MRI is usually sufficient for evaluation of the thrower after conventional radiographs. Therefore, CT is rarely indicated in the workup for the symptomatic thrower suspected of having pathologic internal impingement as it provides only limited information relating to osseous structures. When the clinician is interested in further assessing humeral head version, glenoid version, or a Bennett lesion, however, CT can be particularly useful. In fact, CT still remains the gold standard for evaluation of humeral head and glenoid version that have also been implicated in the development of internal impingement and rotator cuff tears in throwing athletes (12, 13, 14, 61, 62).

Preoperative Management

Despite the clinical and imaging findings relating to pathologic internal impingement, the cornerstone of treatment is nonoperative treatment prior to considering any operative management alternatives. This includes

a period of rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy, and physical therapy. With nonoperative management, the overhead athlete is initially instructed to discontinue throwing with a period of active rest lasting 2 to 6 weeks depending upon the chronicity and severity of symptomatology.

a period of rest, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, cryotherapy, and physical therapy. With nonoperative management, the overhead athlete is initially instructed to discontinue throwing with a period of active rest lasting 2 to 6 weeks depending upon the chronicity and severity of symptomatology.

Our nonoperative rehabilitation program for pathologic internal impingement is structured as a multiphasic sequential approach based upon four phases: acute (phase 1), subacute (phase 2), advanced strengthening (phase 3), and return to play (phase 4) (11, 63). In the early, acute phase (stage 1), pain, possible stiffness, loss of motion, and external rotation and periscapular weakness are characteristic clinical findings in the overhead athlete. Therefore, rehabilitation techniques are targeted at diminishing pain and inflammation while restoring balance in external and internal rotation range of motion, improving strength, and enhancing dynamic stability. To diminish pain and inflammation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cryotherapy, iontophoresis, and laser therapy are utilized.

To improve range of motion and decrease symptoms of stiffness during phase 1, we focus on controlled, mobility exercises, especially targeting internal rotation (i.e., GIRD) and horizontal adduction that are often problematic in the symptomatic, overhead athlete. The essential goal is to restore total rotational motion (external and internal rotation) in the throwing shoulder when compared to the nonthrowing shoulder and reestablish muscular balance (42, 63). Mobility exercises focus on restoring the overhead athlete’s normal total motion arc (i.e., increased external rotation compared to the nonthrowing shoulder) while maintaining external rotator end-range elasticity. It is well established that the overhead thrower exhibits a motion disparity in external and internal rotation range of motion, including a significant increase in external rotation and a substantial loss of internal rotation compared to the nonthrowing side. In the thrower, these alterations in motion are partially adaptive in nature; however, it is unknown how much alteration in motion is acceptable and does not pose a risk factor for shoulder injury.

As one may believe that anterior laxity is a component of internal impingement, stretching of the anterior capsule should be avoided to not potentiate symptoms of microinstability. Appropriate exercises include the supine horizontal adduction stretch, supine horizontal adduction with internal rotation stretch, sleeper stretch, sleeper stretch with a lift, and passive range of motion into internal rotation. Previous studies have shown that GIRD may increase the risk for shoulder injuries; therefore, shoulder stretching programs can be therapeutic as well as preventative (42, 43, 64). It is crucial for an overhead athlete to obtain his or her preinjury or improved total motion arc by 6 weeks, including maximum external rotation, to optimize opportunity for successful return to play.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree