Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression and Rotator Cuff Débridement of Partial- and Full-thickness Tears

Aaron J. Krych

Russell F. Warren

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

External, or outlet, impingement syndrome is a common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction. Table 1-1 shows the etiology of subacromial pathology. Traditionally, these causes have been grouped into structural factors and dynamic factors. Structural factors lead to mechanical obstruction and decreased space for clearance of the rotator cuff within the supraspinatus outlet. The obstruction abrades the rotator cuff, producing tears and

degeneration. When structural factors are the primary cause of subacromial pain, alleviation of the obstruction is curative. Alternatively, dynamic factors can cause secondary subacromial impingement due to superior migration of the humeral head during arm elevation (1). Abnormal superior migration leads to abutment of the greater tuberosity against the coracoacromial (CA) arch and thus tendon injury. Rotator cuff dysfunction and fatigue cause most dynamic imbalance. These patients respond well to rehabilitation of the shoulder musculature, which centers the humeral head within the glenoid fossa during arm elevation. Successful treatment of dynamic impingement due to glenohumeral instability may require operative stabilization to achieve centering (2).

degeneration. When structural factors are the primary cause of subacromial pain, alleviation of the obstruction is curative. Alternatively, dynamic factors can cause secondary subacromial impingement due to superior migration of the humeral head during arm elevation (1). Abnormal superior migration leads to abutment of the greater tuberosity against the coracoacromial (CA) arch and thus tendon injury. Rotator cuff dysfunction and fatigue cause most dynamic imbalance. These patients respond well to rehabilitation of the shoulder musculature, which centers the humeral head within the glenoid fossa during arm elevation. Successful treatment of dynamic impingement due to glenohumeral instability may require operative stabilization to achieve centering (2).

TABLE 1-1 Causes of Subacromial Pathology | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A wide array of conservative treatments for external impingement are usually advocated before surgery is contemplated. These include rest and activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and physical therapy. A recent systematic review included four randomized control trials of conservative versus surgical treatment for subacromial impingement syndrome, and concluded that there were no differences in outcome in pain or shoulder function between the two treatment groups (3). However, no high-quality randomized control trials were available for review in this study. Specifically, the trials included did not have homogeneous groups of patients and included no strict inclusion or exclusion criteria. In addition, duration of symptoms was not similar between the groups in the included studies. This illustrates the need for a more rigorous methodology and standardization of reported outcomes on this common surgical procedure. Currently, surgical recommendations are made on an individualized basis.

Arthroscopic subacromial decompression (ASD) has become a mainstay of treatment for patients with impingement syndrome that has failed conservative management. Since its introduction in 1985, ASD has reliably produced clinical success rates comparable to that of open anterior acromioplasty with better cosmesis, low morbidity, and early return of function (4, 5). The most important indications for ASD are as follows: (a) primary mechanical impingement, (b) partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, (c) massive irreparable rotator cuff tears (where limited decompression combined with tuberoplasty may be helpful), and (d) malunions of the greater tuberosity with superior displacement of less than 1 cm. Malunion of the greater tuberosity with displacement of more than 1 cm is best treated with osteotomy and repositioning of the tuberosity.

Diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint at the time of ASD is extremely useful. The indications are as follows:

When subacromial decompression is being considered for impingement in patients under 40 years old. Instability may be present with impingement and cuff pathology in a significant percentage of these younger patients, especially in those who are overhead athletes (2, 4). Often this instability is subtle, difficult to demonstrate on routine physical examination, and evident only at the time of examination under anesthesia. Arthroscopic examination of the capsuloligamentous complex is valuable in making the diagnosis.

When there is a suspicion of a cuff contusion or partial-thickness tearing of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopic débridement of the cuff is simple and often beneficial (6).

When there is a suspicion of a full-thickness cuff tear amenable to repair. Arthroscopic inspection and probing are instrumental in assessing the ability to achieve a successful repair. Furthermore, recent advances in arthroscopic instrumentation have rendered most tears amenable to repair arthroscopically. As discussed later, when a massive irreparable tear is encountered, débridement of the torn tissue is advantageous and efficiently performed arthroscopically. In this scenario, the CA arch is preserved, while acromial smoothing or a tuberoplasty may be performed.

When the preoperative diagnosis is uncertain. Abnormalities such as labral tears, biceps tendon pathology, synovitis, and adhesive capsulitis may be missed when the glenohumeral joint is not inspected arthroscopically. If left untreated, these problems can lead to residual pain after decompression.

TABLE 1-2 Differential Diagnosis for Impingement Syndrome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

It is worth noting that the impingement syndrome may be confused with other causes of shoulder pain, such as osteoarthritis. Table 1-2 lists other causes of shoulder pain. Isolated subacromial decompression in these patients may not be curative. However, mechanical impingement may occur concurrently with these disorders. Subacromial decompression may provide some pain relief in this setting, but successful long-term treatment depends on management of the primary pathology. Hence, careful preoperative assessment cannot be overemphasized. We feel the subacromial injection test can provide very useful prognostic information, especially in this subset of patients. In a recent prospective cohort study, the mean improvement in Constant score for patients with a negative preoperative injection test was 21 points, compared to 35 points in the group with a positive preoperative injection test (7). All patients had confirmed impingement lesions at the time of arthroscopy. This study emphasizes that patients with a negative preoperative injection test can have significant improvement compared to preoperative scores, but this is a lesser degree than those with a positive result to local anesthetic injection. Patient expectations may be tempered preoperatively based on the results of this test.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The preoperative evaluation of a patient with rotator cuff pathology includes consideration of the history, physical examination, and imaging studies. The history should include the patient’s age, activity level, occupation, and goals. The onset, duration, and severity of symptoms are equally important. Note the effect of prior treatments such as medications, injections, physical therapy, or surgical procedures. Although most patients with full-thickness cuff tears are over 40 years old, there remain a significant number of younger contact and throwing athletes with cuff tears requiring operative treatment. Manual laborers and recreational athletes are also susceptible to cuff injury. Patients with partial-thickness or small full-thickness tears will often complain of pain without weakness. Those with larger full-thickness tears are disabled by weakness as well as pain. The pain associated with rotator cuff disease is often worse at night and keeps the patient awake. Patients with longstanding pain associated with overhead activity are more likely to have a degenerative cuff tear than are patients in whom an acute, traumatic event initiated their symptoms.

Examination

We routinely perform a thorough physical examination of the cervical spine and upper extremity in the patient with shoulder pain. We assess atrophy of the shoulder girdle, active and passive range of motion, strength, neurovascular status, and impingement signs. Proximal rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps is often associated with chronic cuff tendonitis and degeneration. Patients with symptomatic cuff tears have difficulty initiating abduction and present with altered scapulothoracic rhythm. More specifically, a “shrug sign” is present during arm elevation, demonstrated by increased scapulothoracic motion and decreased glenohumeral motion. With the forearm fully pronated, weakness of shoulder elevation indicates a tear in the supraspinatus. Weakness of the external rotators indicates involvement of the infraspinatus. In the largest tears, the patient may not be able to maintain the arm that is passively externally rotated. Lesser degrees of external rotation weakness may be manifest by a “lag” between the amount of passive and active external rotation. Although patients with a massive tear may exhibit full active elevation, strength testing frequently reveals marked weakness. We use the lift-off test and the belly press test to assess subscapularis function (8, 9). Again, glenohumeral instability can be the cause of the impingement and cuff tendonitis in young overhead athletes (2). A careful examination for anterior, posterior, and multidirectional instabilities should be performed.

Diagnostic Imaging

In patients over 40 years old, we obtain routine radiographs of the affected shoulder to assess the glenohumeral joint, acromion, and acromioclavicular (AC) joint. These include anteroposterior (AP) views in internal and

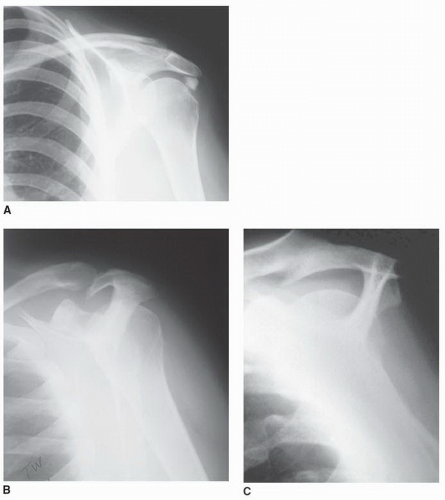

external rotation, an axillary view, and a supraspinatus outlet view. A high-riding humeral head with a narrowed subacromial space suggests a large or massive rotator cuff tear. Calcific tendonitis may be readily apparent on the AP view (Fig. 1-1A), and whether present on internal rotation or external rotation view can help to localize the calcification to supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendon. A curved or beaked anterior acromion, as seen on the outlet view, is often associated with impingement (Fig. 1-1B and C). An axillary view may show an os acromiale. Osteophytes secondary to arthritis of the AC joint can contribute to impingement and cuff tendonitis. In patients under 40 years old, we routinely obtain AP, West Point axillary, and Stryker notch views to better visualize the glenoid rim and to detect Hill-Sachs lesions associated with instability.

external rotation, an axillary view, and a supraspinatus outlet view. A high-riding humeral head with a narrowed subacromial space suggests a large or massive rotator cuff tear. Calcific tendonitis may be readily apparent on the AP view (Fig. 1-1A), and whether present on internal rotation or external rotation view can help to localize the calcification to supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendon. A curved or beaked anterior acromion, as seen on the outlet view, is often associated with impingement (Fig. 1-1B and C). An axillary view may show an os acromiale. Osteophytes secondary to arthritis of the AC joint can contribute to impingement and cuff tendonitis. In patients under 40 years old, we routinely obtain AP, West Point axillary, and Stryker notch views to better visualize the glenoid rim and to detect Hill-Sachs lesions associated with instability.

FIGURE 1-1 A: AP view of left shoulder showing calcific tendonitis. B: Outlet view demonstrating a “curved” type II acromion. C: “Beaked” type III acromion. |

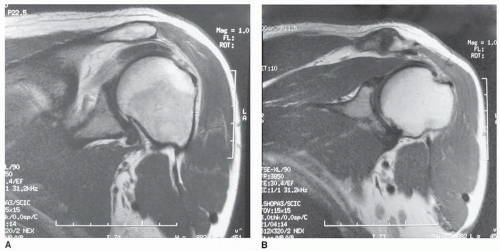

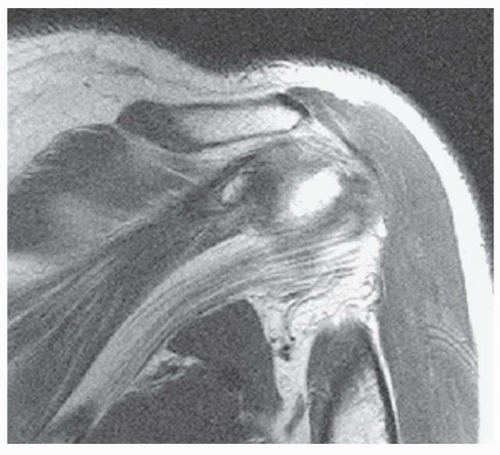

When a rotator cuff tear is suspected, a variety of imaging studies may be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography has emerged as a useful tool because of its ability to obtain dynamic images. However, the utility of ultrasound depends heavily on the experience of the radiologist. At our institution, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred imaging modality. MRI combines accuracy in detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears with comprehensive imaging of the shoulder joint (Fig. 1-2). Furthermore, the MRI scan has the distinct advantage of being able to reveal the size of the tear, the extent of retraction, and the quality of the remaining tissue. Fatty infiltration of the cuff musculature with retraction on MRI examination indicates a poor prognosis (Fig. 1-3). Knowing this preoperatively is important as it may alter the operative plan. Some institutions utilize intra-articular gadolinium to improve diagnostic sensitivity; however, it is not routinely used at our institution. The abduction external rotation (ABER) view for MRI of the shoulder has become increasingly popular, as it has been shown to increase the sensitivity and inter- and intraobserver agreement for detecting partial-thickness tears of the rotator cuff (10), particularly in the throwing athlete when longitudinal tears of the infraspinatus are more easily missed on standard MRI.

SURGERY

Instrumentation

In addition to basic arthroscopic instruments, we use an inflow pump for shoulder arthroscopy (Arthrotek, Biomet, Warsaw, IN or Oratec, Oratec Interventions Inc., Menlo Park, CA). We typically use a 5.5-mm full-radius resector for subacromial decompression. An arthroscopic burr is useful when removing hard bone. We prefer using a tissue ablator (Arthrocare Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) for soft-tissue removal and coagulation.

If a rotator cuff repair is anticipated, we prepare instruments designed for suturing the cuff back to bone. A variety of tacks, staples, and suture anchors are available for this purpose, but we prefer using a suture repair.

If a rotator cuff repair is anticipated, we prepare instruments designed for suturing the cuff back to bone. A variety of tacks, staples, and suture anchors are available for this purpose, but we prefer using a suture repair.

Positioning

Regional anesthesia for shoulder procedures is advantageous because it provides excellent postoperative analgesia without the use of intravenous narcotics. Most patients will require only oral analgesics postoperatively and can be discharged from the hospital on the day of surgery. We prefer to place patients in the beach-chair position. It avoids the potential neural complications that may occur when a patient is in the lateral decubitus position with the arm in traction. It also facilitates freedom to manipulate the humerus during intra-articular examination. Furthermore, we find it easier to convert the arthroscopic procedure to a miniarthrotomy from this position if necessary.

To achieve beach-chair positioning, lower the foot of the table and flex it 20 degrees at the waist after inducing anesthesia. Raise the back of the table so that the patient’s torso is positioned 70 degrees from the horizontal plane. Rotate the upper body roughly 20 degrees so that the operative shoulder is lifted away from the table. Recess the beanbag beneath the operative shoulder so that there is access to the medial aspect of the scapula. After deflating the beanbag, move the patient and beanbag toward the operative edge of the table (Fig. 1-4). Alternatively, a shoulder-specific table with a removable back component may be used to enhance visualization.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree