Arthroscopic Repair of the Rotator Cuff

Curtis R. Noel

Robert H. Bell

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Tears of the rotator cuff mechanism remain one of the more common problems we as orthopaedists treat. Because this is a disease with a broad continuum, patients can present with varying levels of pathology. Rotator cuff defects range from partial-thickness to full-thickness lesions measuring from small, less than 1-cm, tears to massive, irreparable tears. Often these patients will have associated disease of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, biceps tendon, or labrum (1). While impingement from the overlying acromion may be a part of this disease entity, many tears may have either an intrinsic pathology unrelated to the impingement process or an extrinsic cause such as instability (2, 3). As such, surgeons must be careful in their assessment of these patients and understand the origin of the pathology in order to best treat the disease.

The principal indication for rotator cuff surgery is pain. Lack of mobility and diminished strength, while often of concern to the patient, are secondary to that of pain relief. The patient should understand that the intent of the surgery is to remove, if present, the offending acromial prominence and repair the damaged tendons (4, 5). It is important that they realize the result of such surgery is dependent upon many factors including tear size, retraction, fatty infiltration, tissue quality, preoperative mobility, and their overall health (6, 7, 8). Furthermore, they should understand their role in the postoperative rehabilitation and the length of time required for recovery.

Relative and absolute contraindications to this surgery are rare but should include active or recent infection, significant medical comorbidities, and advanced degenerative joint disease or advanced cuff arthropathy requiring arthroplasties. Patients with fixed superior migration of the humeral head, an absent acromiohumeral interval, significant fatty infiltrates, severe atrophy, and marked retraction of tendon edges on MRI are not ideal candidates for an arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and should be recognized preoperatively (6).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients with impingement and associated rotator cuff pathology can and will present with a constellation of physical findings. In most cases, however, the history these patients provide is remarkably similar regardless of the size of the tear. Nearly all of these patients will describe pain with routine overhead activities such as reaching to the top shelf, putting on a coat, and reaching behind their back to hook a bra. They will also complain of an inability to participate in their normal level of recreational activities such as tennis or golf, but the most significant complaint is trouble sleeping. Pain at rest is common in this group of patients owing to the edema of the cuff tendons and secondary inflammation encountered when the patient becomes dependent lying in bed. This night pain classically improves after the patient gets out of bed in the morning and assumes an upright position. Those patients with large and massive tears may describe a more significant functional limitation than those with smaller tears given that they have lost much of their ability to externally rotate the arm and position it for daily activities. Nevertheless, even patients with smaller lesions may have trouble with many activities of daily living due to pain and loss of motion from an occasional secondary adhesive capsulitis (9).

The physical examination may provide some subtle evidence of rotator cuff problems starting with the inspection. Not uncommonly, patients with only moderately advanced cuff disease will have a torn long head of the biceps tendon with the classic “Popeye” muscle appearance (10). The AC joint, if arthritic, will be more prominent and may even have an associated ganglion as the glenohumeral joint fluid leaks up through the absent cuff and inferior capsule of the AC joint (11). If the cuff tear is long-standing and advanced, there will often be empty fossae due to atrophy of the supra- and infraspinatus muscles and a relative prominence of the scapular spine. Palpation will elicit some tenderness if the AC joint is inflamed; however, for the most part, the patient with

rotator cuff disease will be most symptomatic with motion testing and not palpation. Motion should be assessed and recorded both passively and actively. These patients will, depending upon the size of their tear, demonstrate varying losses of both types of motion. Patients with small tears typically will have preservation of both active and passive motion with limitation only due to pain on extremities. As the supraspinatus tear enlarges, the infraspinatus and teres minor become involved, and the patient will begin to lose not only forward elevation but also external rotation. Strength in these planes will decrease as well and may be most noticeable on resisted external rotation. As the tear extends into the external rotators, the patient will have a positive lag sign and horn-blower’s sign. In the largest tears, the arm that is passively positioned in external rotation will be unable to be maintained in this position and may drift back to the neutral, or even internal rotation, position. Similarly, the lift-off test and the belly press, or Napoleon sign, allow the surgeon to test for the integrity of the subscapularis (12).

rotator cuff disease will be most symptomatic with motion testing and not palpation. Motion should be assessed and recorded both passively and actively. These patients will, depending upon the size of their tear, demonstrate varying losses of both types of motion. Patients with small tears typically will have preservation of both active and passive motion with limitation only due to pain on extremities. As the supraspinatus tear enlarges, the infraspinatus and teres minor become involved, and the patient will begin to lose not only forward elevation but also external rotation. Strength in these planes will decrease as well and may be most noticeable on resisted external rotation. As the tear extends into the external rotators, the patient will have a positive lag sign and horn-blower’s sign. In the largest tears, the arm that is passively positioned in external rotation will be unable to be maintained in this position and may drift back to the neutral, or even internal rotation, position. Similarly, the lift-off test and the belly press, or Napoleon sign, allow the surgeon to test for the integrity of the subscapularis (12).

The classic Neer impingement sign will often be positive, as will the Hawkins test and the painful arc (12). All of these help confirm the presence of subacromial impingement and likely cuff pathology but do not necessarily help to quantitate the size of tear. In concert with the test for motion, they do, however, provide enough information to make one suspect larger tears. If the AC joint is pathologic due to painful arthritic changes or an inflammatory arthropathy, the cross-arm abduction test will help to elicit pain localized to the joint.

Diagnostics

There are a number of diagnostic studies that aid surgeons in identifying full- or partial-thickness rotator cuff tears and whether or not they are amenable to arthroscopic repair given their level of technical ability. Arthroscopic rotator cuff surgery requires an understanding of basic shoulder arthroscopy, arthroscopic subacromial decompressions, arthroscopic excisions of the distal clavicle, as well as the repair of superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) lesions, biceps pathology, and capsulolabral disruptions.

Routine imaging begins with radiographic studies of the shoulder, including, but not limited to, a true anteroposterior (AP) of the glenohumeral joint, an axillary view, and an outlet view. These three views will give the surgeon an appreciation for associated glenohumeral degenerative disease, loose bodies, and the relative acromiohumeral interval. Furthermore, the outlet view will demonstrate relative acromial morphology (types I to III) (13), inferior clavicular osteophytes that compromise the outlet, and the potential prominence of the greater tuberosity. Additional views like the Zanca view will better demonstrate the status of the AC articulation, degenerative changes within this joint, and cystic changes consistent with idiopathic osteolysis and its inclination, which may be important in operative planning. Axillary views can also help to demonstrate associated glenohumeral narrowing consistent with early degenerative arthritis, posterior subluxation, and posterior glenoid osteophytes, often seen in throwing athletes.

Arthrography, once the gold standard in defining rotator cuff pathology, is used less often because of the advent of MRI. Although arthrography is a reliable tool for determining the presence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, it is limited in its ability to determine the size of a full-thickness tear or the existence of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears.

Ultrasound is another modality that some surgeons and radiologists have embraced to evaluate rotator cuff tears (14). Despite reports stating its usefulness, we have not relied on ultrasound in our practices. Instead, MRI has become our primary diagnostic method of evaluating the shoulder for rotator cuff tears and other pathologies. MRI allows the surgeon to identify preoperatively the size and characteristics of a rotator cuff lesion, as well as recognize any other potential sources of pain and pathology. A combination of sagittal, tangential, and coronal oblique images allows the surgeon to determine AP and mediolateral dimensions of a tear as well as coexistent atrophic changes and fatty infiltrates within the muscle bodies of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, thereby better defining the age of a rotator cuff tear (6). The existence of such changes coexistent with fixed superior migration of the humeral head on routine AP films of the shoulder should lead one to suspect an irreparable lesion and to consider other treatment options.

Preoperative Counseling

Rotator cuff surgery, in order to be most successful, requires not only a skillful surgeon but also a well-informed patient. A number of teaching aids exist to facilitate the learning process for the patient including written materials, Web sites, and teaching videos. A simple 5-minute video of the doctor discussing the mechanics of the surgery, the postoperative course with potential outcomes, and complications will allay many concerns and make for a ready partner in this recovery process. In these preoperative teachings, we touch on a number of different issues including the following:

The success rate for the arthroscopic approach has proven to be comparable to that of open repairs (15, 16, 17).

The morbidity following the surgery will be less than an open repair but will still encompass pain, requiring analgesics for the first few weeks.

The tendon repair while painful at first will rapidly become less painful over the first month but the actual healing of the tendon to the bone will take as long as 6 months to reach a strength comparable to a normal shoulder. This requires that they protect their repair carefully, especially for the first 2 to 3 months before any strengthening begins.

We typically discharge most patients after their third or fourth visit at the 5- to 6-month mark but inform them that additional gains in motion and strength may take a year.

Many patients ask if they really need to fix the tendon. We tell them that likely half of all tears enlarge over time and become more painful and functionally debilitating but that we can not predict which will do this but that if they have noted a progression of their symptoms that this often indicates a tear that is enlarging and should be addressed (8).

We warn them that if their tear does enlarge it may become irreparable due to size and retraction and may, in rare cases, go on to develop cuff arthropathy.

Patients always want percentages for a procedure and we state an 85% to 90% chance for success, meaning improvement in pain, not necessarily in motion; 10% chance of no improvement; and less than 1% chance of being made worse. Arthroscopic repairs, because they preserve the deltoid, lessen the risk of serious deltoid problems postoperatively, but patients need to be aware of this possibility (4, 18, 19).

The intent of rotator cuff surgery is pain relief, and the patients must understand that the goal of their surgery will be first and foremost to help relieve their pain and any secondary improvement in motion and function, while anticipated, will be a bonus.

Finally, we let all patients know that repairs can fail, early and late, and that the larger the tear, the greater the likelihood of such an occurrence (20). I ask them to keep me apprised of their status during the recovery even after discharge. We do explain that it is common to notice periods of pain during their recovery and that should they be significant we will investigate accordingly.

SURGERY

Operating Room Setup

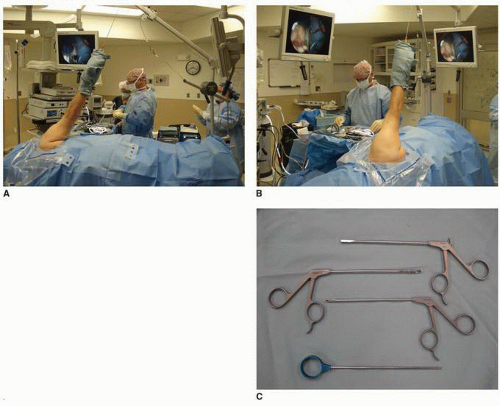

Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair can be performed in either the beach-chair or the lateral decubitus position. Each method has its champions declaring the benefits and defending the drawbacks of that specific patient position. We prefer to do all of our rotator cuff surgeries with the patient in the lateral decubitus position. The surgeon has easy access to the anterior, posterior, and superior aspects of the shoulder, and the arm is held in the appropriate position facilitating tendon reapproximation to the greater tuberosity. In this position, the arm can be freely rotated to facilitate anchor placement and reduce tension during suture tying (Fig. 3-1A and B).

In addition to general anesthesia, we routinely utilize interscalene regional anesthesia for improved intra-operative blood pressure control and postoperative pain relief. Our anesthesiologists use ultrasound guidance to administer the block and add Depomedrol to the anesthetic to prolong its effect for 24 hours or more. After successful intubation, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with an axillary roll placed under the nonoperative arm and a beanbag deflated around him or her to maintain the appropriate position. The patient is allowed to lean back approximately 20 degrees to place the articular surface parallel to the floor. The knees and ankles are well padded to prevent neurologic injury, and the hand is placed in an inflatable device that decreases the risk of potential nerve injury and skin problems. In the vast majority of patients, 10 lbs of traction at approximately 30 to 40 degrees of abduction and 10 to 15 degrees of forward flexion is more than adequate to provide appropriate positioning. Because this device is attached at a single centered hole, internal and external rotation is easily performed allowing for excellent access to the shoulder. The bed is then turned and anesthesia is shifted out of the immediate operative field so that the surgeon and/or the assistant may have unrestricted access to the entire shoulder region: front, back, and top (Fig. 3-1A and B).

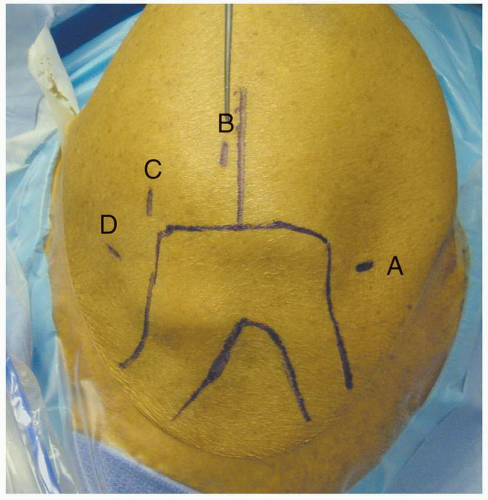

The shoulder is sterilely prepped and draped, and the anatomic landmarks are identified. The anterior, lateral, and posterior acromion is outlined, as well as the AC joint and coracoid (Fig. 3-2). The operating room technician stands on the anterior aspect of the patient, opposite of the surgeon, along with the mayo stand and sterile instrument table (Fig. 3-1A and B). A basic set of instruments is used for almost every arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. An arthroscopic shaver, burr, and radiofrequency (RF) device are needed for the débridement, mobilization, visualization, and bony work necessary to adequately repair the rotator cuff. For the actual tendon repair, we routinely use at least one cannula, a ring grabber, tissue grasper, knot pusher, suture scissors, and several different options for suture passing (Fig. 3-1C).

Portals

Properly positioned portals allow for safe access to the shoulder, a proper field of view, and appropriate angles for instrumentation. Even though multiple safe portals can be established around the shoulder, three basic portals create the foundation for most rotator cuff repairs. The posterior portal is located 1 cm medial and 2 cm inferior to the posterolateral corner of the acromion and is the initial viewing portal (Fig. 3-2). Once inside the glenohumeral joint, the anterior portal is established with an outside-in technique. A spinal needle is introduced lateral to the coracoid entering the glenohumeral joint through the rotator interval. If an arthroscopic distal clavicle excision is planned, this portal can be placed just inferiorly to the AC joint. After switching to the subacromial space, the lateral portal can be established under direct visualization and is normally located immediately anterior to the “finish line” (a line drawn perpendicular to the lateral margin of the acromion beginning at the posterior extent of the AC joint) and 2 to 3 cm lateral to the edge of the acromion (Fig. 3-2), but this portal can be moved based on rotator cuff tear location in order to give the surgeon the best access to the tear.

FIGURE 3-2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|