Arthroscopic Repair of SLAP Lesions

Michael S. Bahk

Stephen J. Snyder

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Clinically significant injuries to the superior labrum are relatively uncommon. A number of arthroscopic shoulder series report an incidence around 6% of all significant shoulder arthroscopy pathology (1, 2, 3). Andrews et al. (4) in 1985 described tears of the anterosuperior labrum in overhead athletes. In 1990, Snyder et al. first described superior labral and biceps anchor pathology as SLAP or superior labrum anterior and posterior lesions. They characterized and classified these lesions as injuries occurring posteriorly, extending anteriorly to and including the biceps anchor (1). Subsequent laboratory studies have defined the biomechanical importance of the biceps anchor (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10), while clinical data report significant pain and prolonged disability in patients with untreated SLAP tears (1, 2, 4). However, diagnosis of SLAP lesions is still challenging even when based on history, physical examination, and modern imaging modalities. Knowledge of the numerous normal anatomic variations is essential to diminishing the likelihood of overdiagnosis of SLAP tears and unnecessary surgical treatment of normal anatomy.

Anatomy

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous ring that extends completely around the edge of the glenoid fossa (11, 12). The anatomy of the superior labrum is unique and different from the other labral areas. The superior labrum is often meniscoid or triangular in shape and not intimately attached to the cartilage having a sublabral recess in 73% of shoulders (13, 14, 15). The sublabral recess is most common at the 12 o’clock position and decreases in incidence inferiorly (15). The superior labrum is also more mobile with variable attachment in the anterosuperior quadrant. Conversely, the inferior labrum is rounded, firmly attached, and continuous with the glenoid (14). Some investigators hypothesize that the superior labrum may act as a mobile extension of the superior glenoid, while the inferior labrum may act as a stabilizing bumper (14).

The long head of the biceps tendon originates from the superior labrum and supraglenoid tubercle in varying degrees (11, 16, 17). However, the biceps arises predominantly from the labrum with little contribution from the supraglenoid tubercle in some shoulders (11, 16). The supraglenoid tubercle lies 5 mm medial to the superior glenoid rim (11, 17). The biceps origin may vary from the 11 to 1 o’clock position; however, in 55% of shoulders, it arises predominately from the posterior labrum. It has an equal anterior and posterior labral origin in 37% of shoulders (17).

The superior glenohumeral ligament predominantly arises from the supraglenoid tubercle with some fibers arising from the biceps-superior labral origin (15). The middle glenohumeral ligament attachment is variable. It may arise from the superior labrum at the biceps anchor, the anterior superior glenoid, or the adjacent labrum and is described as sheet-like typically and obliquely draped over the subscapularis tendon (18).

There are three important normal variations of the anterosuperior quadrant of the glenoid having an overall incidence of 13% to 14% (19, 20). The most common variation is a sublabral foramen (9%) with a cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament attaching directly to the anterosuperior labral tissue (19, 20). Three percent of shoulders have a sublabral foramen and 1.5% possess a Buford complex. This important variation consists of complete absence of all anterosuperior labral tissue but possesses a robust cord-like middle glenohumeral ligament that attaches directly to the base of the biceps tendon/labral junction (19, 20). It is important to understand these normal variations to avoid overdiagnosis of SLAP lesions or “repair” of normal anatomy that may severely restrict motion.

Biomechanics

Biomechanical studies have shown that a competent biceps-labral complex provides translational and rotational stability to the glenohumeral joint. Proper repair of a SLAP tear should restore normal biomechanics (21).

Short head biceps contraction allows proximal humeral migration. However, this is counterbalanced by humeral head depression with contraction of the long head of the biceps. Release of the long head of the biceps results in an increase in proximal humeral migration by 15.5% with elbow flexion and supination (5).

In the vulnerable position of abduction and external rotation, the shoulder is stabilized with biceps contraction. Anterior displacement is reduced with increased biceps tension, even with the presence of a Bankart lesion (6). Electromyographic studies have also reported peak biceps activity in the late cocking phase of throwing for baseball pitchers and noted higher biceps activity in players with known chronic anterior instability (7, 8). Creation of a SLAP lesion in a cadaveric model decreases torsional rigidity in the overhead position and increases inferior glenohumeral strain (9).

Superoinferior and anteroposterior translation in the lower and middle ranges of abduction increases with a type 2 SLAP lesion because of the subsequent laxity of the superior and middle glenohumeral ligaments that often originate from the superior labrum (10). Loss of an intact labral complex additionally reduces stabilizing forces of concavity compression associated with the loss of biceps contraction (10). SLAP tears increase translation but also allow more external rotation in a cadaveric model. Arthroscopic repair restored range of motion to normal without the need for additional capsular plication (21). In other words, an intact biceps anchor and biceps contraction helps to stabilize the shoulder.

Classification

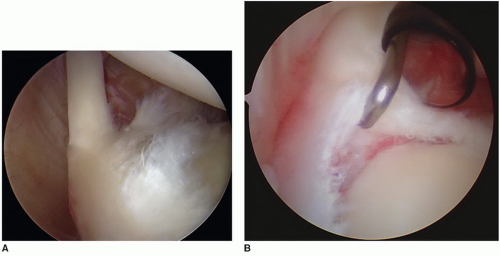

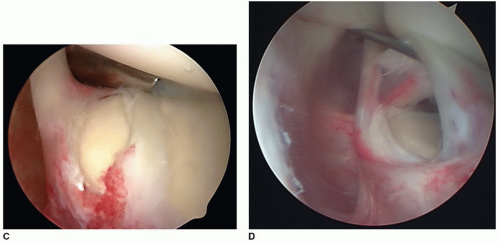

In 1990, Snyder et al. classified SLAP tears into four main types (Fig. 12-1A-D) (1). Others have added to this classification system over time (22, 23, 24).

Type I lesions consist of degenerative fraying of the superior labrum, but the biceps anchor and labrum are firmly attached to the glenoid. Snyder et al. (2) reported a 21% incidence in their study population. This lesion is part of the normal degenerative process of aging and is more common in middle-aged to older patients. It is unlikely a source of significant clinical symptoms.

Type II lesions represent a pathologic detachment of the biceps-labral anchor from the glenoid and are the most common SLAP lesion (55%) (2). It is important to evaluate the shoulder for instability in the presence of a type II lesion because the superior and middle glenohumeral ligaments often originate from the biceps anchor area and may be detached as well.

Type III lesions are bucket-handle tears of a meniscoid superior labrum and occurred in 9% of the study population (2). The biceps tendon anchor is normal and firmly attached to the rest of the labrum and supraglenoid tubercle.

Type IV lesions are bucket-handle tears of the meniscoid superior labrum with the extension of the tear into the biceps tendon (2). These lesions occurred in 10% of patients.

There may be combinations of these SLAP lesions. Most commonly, type III and type IV tears may have a type II component or a detached biceps anchor. They can be described as a complex type II and III or complex type II and IV (25).

Type II SLAP tears have also been subclassified into three groups—anterior, posterior, and combined anterior and posterior lesions (22). Type II SLAP tears with posterior extension may occur by a peel-back mechanism in younger overhead or throwing athletes (22, 26). The “drive-through sign” was corrected after SLAP repair in these patients. Type II SLAP lesions are thought to create a pathological pattern of motion that may lead to additional injuries such as posterior partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (22).

Clinical History

The diagnosis of SLAP tears can be difficult since the clinical presentation is variable and is often associated with additional shoulder pathologies. The history can be nonspecific with patients reporting prolonged, vague shoulder pain or disability that does not improve with conservative management and is exacerbated with specific overhead motions (1). Patients may complain of mechanical symptoms if a torn fragment is trapped between the humeral head and glenoid (1). Forty-nine percent of patients noted mechanical catching or grinding in a large series (2). SLAP tears have a high incidence of associated shoulder pathologies including rotator cuff tears, instability, and ganglion cyst formation complicating diagnosis (1). One large series reported 22% of SLAP lesions were associated with Bankart lesions, while 40% were associated with either full- or partialthickness rotator cuff tears (2). Only 28% of SLAP lesions were isolated lesions (2).

The typical patient to develop a SLAP Lesion is a young male who either sustains a traumatic injury or is involved with chronic overhead activity. Snyder et al. (1, 2) reported 91% of the patients being male with an average age of 38 years. Traumatic injuries often occur with either a traction mechanism of injury from a sudden pull on the arm or a compressive injury such as a fall onto an outstretched arm (1, 23, 28, 29, 30). Cadaveric models have reproducibly created SLAP tears with both these traumatic mechanisms (29, 30). Patients with SLAP tears associated with gradual overhead activity may present a distinct group with different characteristics. The “dead arm” symptom or the sudden painful inability to throw a ball with usual velocity has been hypothesized to be a result of SLAP lesions (31). Throwers’ SLAP tears or posterior SLAP lesions were found in younger men with an average age of 24 years. These tears may occur with a peel-back phenomenon as the labrum undergoes pathological torsion in the abducted externally rotated throwing motion (22).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree