Arthroscopic Repair of Posterior Instability

Craig S. Mauro

David W. Altchek

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Recurrent posterior instability of the shoulder is much less common than anterior instability. The incidence of posterior instability is reportedly between 2% and 12% of all shoulder instabilities (1, 2). Historically, management of posterior shoulder instability has been complicated by recurrence rates ranging from 7% to 72% with operative management and 16% to 96% with nonoperative management (2, 3, 4). Many of the failures with operative treatment have been attributed to unrecognized multidirectional instability (5). Nonoperative management comprises a formal physical therapy program with emphasis on strengthening of the posterior deltoid, infraspinatus, and teres minor (6). Arthroscopic management of this difficult problem continues to evolve. Several authors have demonstrated successful arthroscopic augmentation of the glenolabral concavity, reduction of capsular laxity, and repair of traumatic labral lesions of the posterior glenoid (1, 7, 8, 9).

Patients with posterior instability often present with positional symptoms, in which posterior subluxation of the humeral head occurs when the arm is adducted at 90 degrees of flexion. These patients typically present with posterior shoulder pain with or without distinct symptoms of instability. Biomechanical evaluation of posterior shoulder translation has demonstrated a continuum between subluxation and dislocation (10). Pain is exacerbated by activities that posteriorly load the shoulder in the adducted position (bench press or push-up exercises) (5, 8). Most commonly, trauma to the affected extremity (fall onto an outstretched arm, blow to a forward-flexed adducted arm) precedes the onset of symptoms. However, patients rarely report a history of frank posterior dislocation (2, 8). The etiology of the injury may also be attributed to chronic overuse that leads to microtrauma and the development of laxity of the capsulolabral complex (4, 7). Athletic activities that predispose the individuals to posterior capsulolabral injury include baseball, softball, football, swimming, and volleyball (5, 11).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

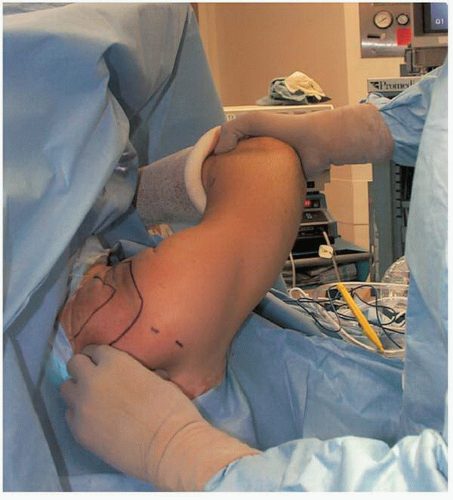

Physical examination may reveal posterior joint line tenderness, crepitance with range of motion (ROM), posterior subluxation, or dislocation. The posterior load-and-shift maneuver (forward flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) is often positive in this patient group and suggests the presence of a posterior Bankart lesion (Fig. 6-1).

Patients with suspected posterior shoulder instability upon history and physical examination should be evaluated with anteroposterior radiographs in internal and external rotation, to rule out a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, and an axillary view, to rule out a posterior bony Bankart lesion and to assess glenoid version. Magnetic resonance imaging is critical for the assessment of the posterior labrum and to rule out other intra-articular pathology (Figs. 6-2 and 6-3). Ultimately, the surgical procedure chosen is dependent on the findings at examination under anesthesia and diagnostic arthroscopy. Arthroscopy is a reasonable first step for all patients under consideration for posterior stabilization. Patients with multidirectional instability or poor tissue quality may sometimes be better stabilized by an open technique. In addition, voluntary dislocators may be better treated by an open procedure and education to avoid positions of provocation (12).

FIGURE 6-1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|