Arthroscopic Repair of Involuntary Multidirectional Instability

Neil Ghodadra

Seth L. Sherman

Matthew T. Provencher

Anthony A. Romeo

INDICATION/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder continues to be particularly difficult to diagnose and treat effectively. Despite recent advancements in the index of suspicion and understanding of the pathophysiology of shoulder instability, the relative infrequency of MDI makes treatment decisions difficult. Most patients with true MDI will have decreased pain and improved stability with a rigorous shoulder strengthening and rehabilitation program. An increased awareness and understanding of clinical symptoms and exam findings in patients with voluntary versus involuntary MDI have led to more appropriate patient selection criteria for surgical stabilization. In particular, patients with a history of voluntary shoulder dislocation and psychiatric issues should not be treated surgically in lieu of higher failure rates.

Surgical stabilization of patients with MDI should be considered in patients with symptomatic, involuntary shoulder instability who have failed a 6-month trail of physical therapy directed at scapular stabilization, rotator cuff, and deltoid strengthening exercises. Young, athletic patients with instability or generalized ligamentous laxity due to a traumatic event are less likely to respond to therapy compared to patients whose pathology stems from repetitive microtrauma (1, 2, 3). Although patients with a traumatic etiology to shoulder instability are likely to have glenohumeral copathology such as a Bankart lesion, this does not preclude a trial of conservative treatment.

The key to providing the patient with the optimal outcome is to be aware of the contraindications to surgical intervention. Patients with documented emotional or psychiatric disorders should be treated with conservative options. In addition, an accurate history and exam are essential to identify voluntary muscular instability, glenoid aplasia, axillary or suprascapular nerve injury, secondary gain issues, or previous history of noncompliance as potential pitfalls for surgical intervention and contraindications to surgery. Patients with voluntary positional instability have subluxation episodes in the provocative position for posterior dislocation (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) or the anterior dislocation (90 degrees abduction and external rotation). In our experience, patients who present as revision cases without the aforementioned contraindications can be treated successfully with revision arthroscopic stabilization and capsule-labral plication.

For patients who have involuntary MDI who have failed a 6-month trial of conservative treatment, we prefer arthroscopic stabilization to open capsular shift techniques. Improvements in arthroscopic techniques have led to a shift from open to arthroscopic stabilization that allows for an outpatient procedure with potentially decreased risk of complications such as subscapularis rupture or postoperative subscapularis insufficiency. With improvements in current implants and arthroscopic techniques, a successful stabilization procedure for patients with MDI can be attained. However, obtaining an accurate history and physical along with at least a

6-month course of aggressive therapy that includes scapular stabilization and dynamic stabilizer strengthening protocols is paramount for a successful outcome. An advantage of placing the patient in a prolonged therapy program is that it allows the patient and surgeon to assess compliance and improvement and create a working relationship through which the surgeon and patient can effectively participate in postoperative rehabilitation.

6-month course of aggressive therapy that includes scapular stabilization and dynamic stabilizer strengthening protocols is paramount for a successful outcome. An advantage of placing the patient in a prolonged therapy program is that it allows the patient and surgeon to assess compliance and improvement and create a working relationship through which the surgeon and patient can effectively participate in postoperative rehabilitation.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients with MDI often present with symptoms of pain, decreased athletic performance, loss of strength, and feelings of subluxation (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). An accurate assessment of a patient with suspected MDI includes a comprehensive history and physical exam as well as appropriate radiographs. In diagnosing MDI, it is paramount to determine the directions of instability by identifying the provocative positions that reproduce the symptoms associated with instability. MDI is diagnosed as instability of the shoulder in more than one direction, which can be posterior and inferior, anterior and inferior, or all three. The key is that instability is the symptomatic finding of shoulder laxity and clearly reproduces the patient’s symptoms in the provocative positions of anterior, posterior, or inferior shoulder instability testing. Patients with inferior instability complain of symptoms while carrying heavy objects at their side, whereas patients with anterior instability experience apprehension when their arm is abducted and externally rotated. Individuals with an element of posterior instability will note feelings of subluxation when the arm is forward flexed and internally rotated.

In obtaining a thorough history, it is important to determine whether the patient’s initial instability episode was secondary to a traumatic or nontraumatic event. Patients with a traumatic etiology to MDI can report pain during subluxation episodes and global instability. Usually, patients with MDI will complain of a history of multiple episodes of involuntary dislocation or subluxation that usually do not require intervention by a physician for reduction. Complaints of subluxation events during sleep and difficulty carrying weight at the side are common in individuals with MDI.

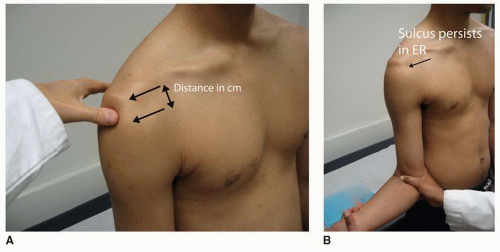

A comprehensive physical exam is essential in the proper evaluation of a patient with suspected MDI. The patient should be assessed for joint hyperlaxity at the elbows, knees, and thumb and should be queried to voluntarily sublux his or her shoulder posteriorly. Bilateral shoulders should be evaluated for scapular dyskinesia, obvious dislocation, or excessive hyperlaxity. Patients with posterior instability may have a mild loss of internal rotation and tenderness to palpation along the posterior joint line. Provocative maneuvers will help determine the direction and degree of instability. Patients who have a painful posterior jerk test have a higher nonoperative failure rate compared to patients who do not have this exam finding (11). In addition, documentation of a symptomatic inferior sulcus (creation of a 1-cm divot between the humeral head and acromion with downward traction of the humerus) exam along with either anterior or posterior instability is essential to the diagnosis of MDI (Fig. 7-1A and B). Internal rotation strength can be decreased up to 30% in patients with MDI and further highlights the dynamic muscle dysfunction in patients with MDI (12). A useful test for inferior capsular laxity

associated with MDI is the Gagey test. The Gagey test is performed as the shoulder is taken through a range of passive hyperabduction with the scapula held stabilized. The Gagey test is positive when hyperabduction is greater than 105 degrees, implying inferior capsular laxity.

associated with MDI is the Gagey test. The Gagey test is performed as the shoulder is taken through a range of passive hyperabduction with the scapula held stabilized. The Gagey test is positive when hyperabduction is greater than 105 degrees, implying inferior capsular laxity.

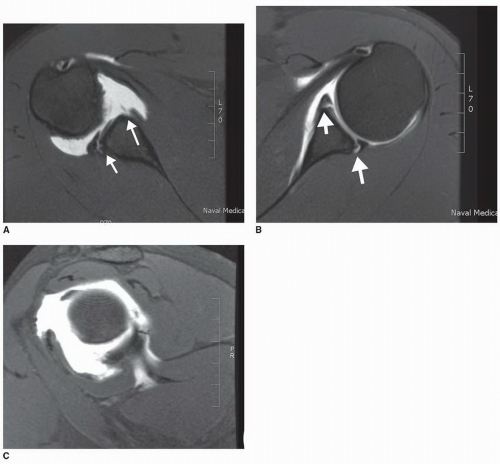

Although patients with MDI have normal radiographs, a complete instability series of x-rays should always be obtained at an initial visit as patients can have concomitant shoulder pathology or a history of traumatic dislocation that can alter the treatment plan. This series consists of glenohumeral AP views in neutral, internal and external rotation, axillary lateral, west point axillary, and Stryker notch view. These views allow for evaluation of humeral head displacement on the glenoid, Hill-Sachs lesions, bony Bankart pathology, fractures of the lesser and greater tuberosities, glenoid aplasia or rim defects, and fractures. In addition, the AP radiograph can reveal inferior subluxation of the humerus on the glenoid. In patients with suspected glenoid hypoplasia, bone loss, and retroversion, a CT scan with 3-mm cuts with and without humeral head subtraction should be ordered. In addition to radiographs for patients with suspected MDI, the authors’ preferred choice of advanced imaging is an MRI and MR arthrogram (MRA) to further delineate soft-tissue pathology involving the rotator interval, biceps, capsulolabral structures, and the rotator cuff (Fig. 7-2A-D).

Electromyographic findings can be abnormal in patients with MDI. In particular, the deltoid, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus have atypical activity and suggest a neuromuscular aspect to shoulder instability (13, 14). In addition, there is an increased stretch reflex in MDI leading to alterations in proprioception with reaching activities (15). Altered EMG findings in MDI highlight the decreased capability of dynamic centering of the glenohumeral joint and further lend credence to the concept of targeted muscle exercises during therapy.

Often patients with MDI will have altered scapular mechanics including medial scapular winging that is muscular based, inferior tip rotation, and poor scapular protraction against the chest wall. It is crucial to evaluate progress with a focused scapular retraining program prior to embarking on surgical intervention for optimal success.

Often patients with MDI will have altered scapular mechanics including medial scapular winging that is muscular based, inferior tip rotation, and poor scapular protraction against the chest wall. It is crucial to evaluate progress with a focused scapular retraining program prior to embarking on surgical intervention for optimal success.

An examination under anesthesia should be performed in the operating room prior to arthroscopy to corroborate suspected directions of instability. Once MDI is evaluated, diagnostic arthroscopy of the glenohumeral joint can reveal patulous capsular tissue and a positive drive-through sign in which the scope can be driven from anterior-superior to anterior-inferior with ease. In addition, arthroscopy can assist the surgeon in diagnosing concomitant pathologies such as a traumatic Bankart lesion, Hill-Sachs lesion, or glenoid bone loss. With advancements in implants and arthroscopic techniques, significant labral pathology and capsular laxity can be addressed at the time of surgery.

SURGERY

Open treatment of MDI has served as the gold standard with correction of inferior capsular pathology. However, results for the open procedure have been mixed with success rates in the literature from 40% to 91% (7, 10, 16, 17, 18, 19). These results are likely due to the larger surgical dissection with subscapularis takedown and the biomechanical properties of the posteroinferior capsule and labrum that differ from the anterior labrum. With the advances in arthroscopic technique, surgeons can stabilize the shoulder using less surgical dissection and have an increased ability to identify and treat concomitant pathology and the posteroinferior capsulolabral complex. However, the ability to recreate open surgical techniques with arthroscopy is technically challenging and requires a consistent operative strategy, which we will outline.

PATIENT POSITIONING

The procedure can be performed with either interscalene block or general endotracheal anesthesia with an interscalene block. We prefer the latter as it allows for using the interscalene block for postoperative pain control.

Both the beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions can be used for the arthroscopic treatment of MDI. However, we prefer to use the lateral decubitus position as it has been shown to more effectively create space in the inferior and posterior quadrants of the shoulder and thus it allows easier access to these areas with strategically placed arthroscopic portals (20, 21). The patient is placed on a beanbag on the operating room table in the lateral decubitus position. An axillary roll and pillows under the fibular heads are placed. Once the patient is placed into the lateral decubitus position, an examination under anesthesia is performed. At this point, a loadand- shift test and a sulcus sign test are performed. If the patient has a 2+ to 3+ sulcus sign that remains 2+ or greater in external rotation, it is pathognomonic for MDI, as long as the patient was symptomatically unstable in this direction. To improve access in this position, the arm is abducted 65 degrees and flexed approximately 15 degrees with an overhead traction sleeve. A pillow bump can be placed under the axilla to create more space in the posteroinferior aspect of the shoulder. We prefer to rotate the table almost 180 degrees to provide complete, unobstructed access to the anterior and posterior portals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree