Arthroscopic Calcium Excision

Steven J. Klepps

Chunyan Jiang

Evan L. Flatow

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Calcific deposits in the rotator cuff with associated tendinitis are a common cause of shoulder pain, peaking in the fourth and fifth decades of life. Symptomatic calcifications are usually located on or within the supra-spinatus tendon adjacent to the insertion on the greater tuberosity but can be associated with tendons of the subscapularis, infraspinatus, and teres minor. The etiology of this condition remains unclear. Uhthoff (1, 2) have stated that the calcifications are a cell-mediated response with minimal degenerative etiology, whereas others think there is a significant degenerative component (3). Calcific tendonitis generally runs a self-limited course not requiring surgical intervention (4, 5). Some patients, however, have symptoms that do not completely resolve with nonoperative treatment.

Many authors have described different stages of the calcification process, usually termed “formative,” “resorptive,” and “chronic” (2, 6, 7). In the formative phase, calcium crystals are deposited in matrix vesicles and the calcium appears chalk-like if removed. The resorptive phase is characterized by spontaneous resorption of calcium with an influx of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. In this stage, the calcium deposit can be grossly characterized as thick and creamy. It is during this phase that pain usually occurs and patients seek medical attention. The chronic phase is generally defined as persistent symptoms and radiographic evidence of calcific tendonitis that does not resolve within 6 months.

Much has been written about nonsurgical treatment of both acute and chronic calcific tendonitis. Initial treatment, regardless of stage, is frequently direct needling of the lesion followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy. An 18-gauge needle is used for placing multiple stabs within the calcific deposit, which is localized both by identification of the point of maximal tenderness and by plain radiography. After needling, an injection of lidocaine, Marcaine, and steroid is placed within the subacromial space to alleviate the pain and the inflammatory reaction stimulated by the release of the calcium. Multiple studies have reported success using this treatment (7, 8) (Fig. 11-1). The injection may be repeated unless the patient receives no relief from the initial injection. The indications for surgical intervention differ in patients who have acute calcific tendonitis versus those with chronic calcific tendonitis. In acute calcific tendonitis, if the patient has failed to respond to direct needling and anti-inflammatory medication, surgical intervention should be considered. In a patient who presents with chronic shoulder pain and evidence of chronic calcific tendonitis, nonoperative treatment, including medication, injection, and rehabilitation efforts, may be considered for a minimum of 6 months.

Another option for patients in the acute stage of disease who have failed to obtain relief from the injection is the use of shock-wave therapy (9, 10, 11). Although promising short-term and midterm results have been reported in acute and chronic conditions, no large series or long-term results have been described. This may be especially useful in patients in the acute phase who have failed conservative treatment.

The contraindications for surgical treatment of acute or chronic calcific tendonitis are few but include patients not considered medically stable and those whose level of symptoms do not warrant surgical treatment. In those patients in whom chronic calcific tendonitis is accompanied by a painful limitation of range of motion and who have failed nonoperative treatment, surgical treatment may include addressing the limited range of motion by manipulation, lysis of adhesions, or selective capsular releases.

Although open techniques have been successful (3, 6), there are several advantages to the arthroscopic technique, including (a) better evaluation of the entire glenohumeral joint and rotator cuff status; (b) ability to

assess the subacromial space for evidence of an impingement lesion as well as to perform a decompression; and (c) reduced disruption of the deltoid with less likely morbidity (12–14). An investigation comparing con-servative treatment to surgical treatment for calcifying tendonitis was reported by Wittenberg et al. (15). In that study, 100 patients underwent a matched-pair analysis. The authors concluded that conservative treatment for calcifying tendonitis leads to less favorable long-term results than surgical treatment. Surgery shortens the painful period and may reduce the number of future rotator cuff ruptures.

assess the subacromial space for evidence of an impingement lesion as well as to perform a decompression; and (c) reduced disruption of the deltoid with less likely morbidity (12–14). An investigation comparing con-servative treatment to surgical treatment for calcifying tendonitis was reported by Wittenberg et al. (15). In that study, 100 patients underwent a matched-pair analysis. The authors concluded that conservative treatment for calcifying tendonitis leads to less favorable long-term results than surgical treatment. Surgery shortens the painful period and may reduce the number of future rotator cuff ruptures.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

There are few conditions in orthopaedic surgery as dramatically painful as acute calcific tendonitis of the shoulder. The patient frequently gives a history of some increase in activity followed by the onset of shoulder pain, which, gradually, over a period of several hours or days, becomes progressively severe and incapacitating. The patient frequently will hold the arm in a protected position, as any voluntary movement is exquisitely painful. Range of motion is difficult to test because of the severity of pain, and there is often guarding and muscle spasm. The tendon that is involved in the acute process is usually exquisitely tender; this may be a helpful sign for localization of the involved tendon and for localization of the needle to aspirate the calcium acutely. The patient who presents with chronic shoulder pain and associated chronic calcific tendonitis is often unable to be thoroughly examined to assess range of motion, strength, and point of maximal tenderness. Patients who have chronic calcific tendonitis and who have normal passive range of motion may exhibit many of the findings of subacromial impingement, including a positive impingement sign and pain with movement of the involved tendon under the coracoacromial arch. Because of this, it is difficult to separate noncalcific subacromial impingement syndrome from that which is associated with chronic calcific tendonitis.

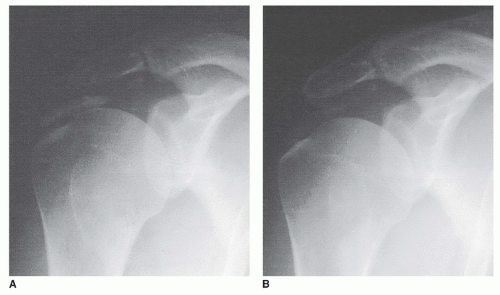

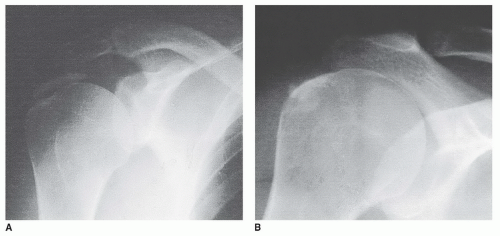

Diagnostic imaging is helpful in localizing the calcium deposit. A routine shoulder series is performed, including anteroposterior views in the frontal and scapular plane and, if necessary, in internal and external rotation (Figs. 11-2 and 11-3) as well as an axillary and supraspinatus outlet view (Fig. 11-4A–C). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans (Fig. 11-4D) may also aid in locating the calcium deposit.

If time has elapsed between the initial radiograph showing calcific deposit and surgical treatment, it is wise to repeat a radiographic series, since ongoing shoulder pain may persist from bursitis and subacromial scarring, even if no radiographic evidence of calcium exists. An up-to-date radiographic series may permit the frustrating operative search for an already resorbed calcium deposit.

FIGURE 11-2 Calcification within the supraspinatus seen on the anteroposterior views in external rotation (A) and internal rotation (B). |

The calcium deposit is evaluated for location and evidence of homogeneity (16). Most calcium deposits requiring surgery are located in the supraspinatus tendon. In addition, to localize the calcium, the outlet view is used for determining the acromial morphology and the presence of any subacromial osteophytes. Less commonly, the deposits may be located within the infraspinatus seen posteriorly.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree