Arthroplasty in Synovial-Based Arthritis of the Elbow

I. A. Trail

INTRODUCTION

“Synovial-based arthritis” is a term that encompasses all forms of inflammatory arthritis affecting the elbow joint. By definition this will exclude primary osteoarthritis, arthritis secondary to fracture or instability, or avascular necrosis. The most common inflammatory condition is rheumatoid arthritis followed by the seronegative conditions including psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and pigmented villonodular synovitis. The relative incidence of these conditions, however, remains unknown, although it is held that approximately 50% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have some involvement of one or both elbows during their lifetime.

The aim of this chapter is to guide the reader through the present status of arthroplasty in the treatment of patients with synovial-based arthritis of the elbow, provide a description of the pathologic processes that follow the onset of an inflammatory arthritis, and discuss the treatment options open to the surgeon.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Inflammatory arthritis can be classified clinically as a disease that predominately affects the soft tissues or predominately has bony involvement. Generally however, most clinicians grade rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow by the x-ray appearances using the Larsen grading system (Table 25-1). Stage 1 involves the soft tissues only and as a consequence has a normal or near normal x-ray; Stage 5 includes extensive bony loss with erosions; Stages 2,3, and 4 lie in between, having varying degrees of bone involvement. Arthroplasty as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis is typically reserved in Larsen Stages 3, 4, or 5. The significance of

the latter being that there must be satisfactory bone stock to support the insertion of an arthroplasty.

the latter being that there must be satisfactory bone stock to support the insertion of an arthroplasty.

At this time, there are no accurate data on how frequently the elbow is involved in patients who suffer with synovial-based arthritis. Souter (1) gave a figure of 50%. It is obvious to any clinician treating this patient group that the vast majority never require surgical intervention, least of all an arthroplasty. Indeed, little is known about why a shoulder or a wrist may become more involved than an elbow in any particular patient (or vice versa). There is some evidence of an association between loss of pronation and supination in the forearm and shoulder involvement; specifically, if patients lose the ability to prosupinate the hand and wrist, they must compensate by abducting and adducting the shoulder. There is, however, no known such association with the elbow.

The clinical significance of involvement of the elbow by an inflammatory arthritis can be catastrophic. Patients suffer not only with pain but also loss of strength and movement; the latter can result in difficulties with certain basic tasks, such as attending to toileting and feeding. The ability to get one’s hand to the mouth is of obvious importance; if this is lost bilaterally, the patient often will require permanent nursing care. In addition, the ulnar nerve may be compressed as a direct result of synovitis or deformity and may result in long-term sensory and motor deficit to the hand.

With regard to the natural history of the disease it is important to remember that rheumatoid arthritis is essentially a progressive process. Although there may be episodes of relapse and remission, the disease tends to progress, albeit at an unpredictable rate. It is estimated that 80% of patients can expect a chronic slow progression of the disease process. As stated previously, the disease initially manifests as an intense synovitis, which distends the joint capsule, causing pain and loss of movement. If this stage is prolonged, the patient can permanently lose movement, particularly extension. In addition, the synovitis will affect the capsule and ligamentous support around the elbow, leading to attenuation of the medial and lateral collateral ligament complexes and resulting in gross instability. Involvement of the proximal radioulnar joint can occur, including damage to the annular ligament. This can result in instability of the radial head. Evaginations of synovium through the capsule can result in compression not only of the ulnar nerve medially but also into the forearm anterolaterally, resulting in radial nerve dysfunction. As the disease progresses, the hyaline cartilage of the elbow can be affected, resulting in destruction of the articular surface. In an inflammatory group this will result predominately in articular erosion including cyst formation. Sclerosis and osteophyte formation, although seen, is less prominent than in the osteoarthritic elbow.

TABLE 25-1 LARSEN CLASSIFICATION OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

CLINICAL EVALUATION

The clinical evaluation of patients with inflammatory arthritis of the elbow involves an assessment of the elbow itself and all the lower limb joints and the shoulder, hand, and wrist on the ipsilateral side. An appreciation of the systemic nature of these processes is critical because involvement of the cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal systems can affect the postoperative management of these patients.

A careful history should be elicited and should include the duration and severity of the patient’s pain. It is important to establish that the elbow is the patient’s most painful joint and the principal requirement for analgesia. The requirement for strong analgesia and the presence of sleep disturbance are good indications for arthroplasty. Second, an assessment must be made of the patient’s mobility (i.e., flexion and extension as well as pronation and supination of the forearm). At the same time, symptoms of elbow instability or ulnar nerve pathology should be noted. Finally, an assessment of the functional disability from the elbow should be made. This generally takes the form of a series of questions related to the ability to undertake tasks with the arm away from or close to the body. These should also include activities with the arm loaded. There are now a number of validated evaluation systems such as the DASH, which give a score for disabilities experienced by the patients. It should be noted, however, that the DASH system evaluates the whole upper limb and is not specific to the elbow. At this time there is no validated score specifically for the elbow, although a number are available (e.g., American Shoulder and Elbow Society Elbow Score, the Mayo elbow score, and others under construction). Undoubtedly the use of these specific elbow evaluations will become more widespread and will allow results between institutions and with varying implants to be compared. A number of clinicians favor more general evaluations such as the Short Form 36 (SF36). However, there is a concern that the SF36 may not be sensitive enough to reflect significant change in the elbow, particularly in a patient with inflammatory arthritis.

Physical examination should be undertaken in the standard fashion. Inspection should identify any cutaneous manifestations of the disease process including the presence of rheumatoid nodules. The skin needs to be carefully evaluated for previous surgical incisions and the quality of

the skin. Patients who have been undergoing steroid therapy for a prolonged period can have very atrophic skin, which must be handled with care. The significance of the scars depends principally on their site and when they were made. Older and more lateral or medial scars can often be ignored. More recent scars, however, will have to be incorporated into the approach. Finally it is also important to note any deformity because this can also modify the approach and surgical procedure.

the skin. Patients who have been undergoing steroid therapy for a prolonged period can have very atrophic skin, which must be handled with care. The significance of the scars depends principally on their site and when they were made. Older and more lateral or medial scars can often be ignored. More recent scars, however, will have to be incorporated into the approach. Finally it is also important to note any deformity because this can also modify the approach and surgical procedure.

Range of motion in flexion and extension as well as pronation and supination should be measured by the use of a goniometer. It is important to differentiate between active and passive movement. In addition, the stability of the elbow should be evaluated with the arm against the side and away from the body. It is not unusual for a patient to maintain a stable fulcrum with the arm against the side only to demonstrate instability with the arm away from the body. Although there are a number of ways of classifying instability, I believe it is most useful to measure varus and valgus instability at both maximum extension and at 60 degrees of flexion. The degree of instability is recorded in degrees using a goniometer for measurement. Finally, an assessment of ulnar nerve function distally should be undertaken. This will require both a sensory and motor evaluation, the latter typically being assessed by grip strength.

IMAGING STUDIES

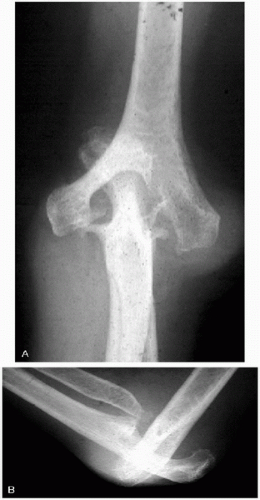

The principal imaging modality in inflammatory-based arthritis of the elbow is plain radiographs. It is essential in all patients with an inflammatory arthritis, particularly if they are proceeding to surgery, that both anteroposterior (AP) and lateral x-rays are obtained. Better visualization can be obtained by undertaking separate AP x-rays of both the distal humerus and ulna. This is particularly helpful if the patient is unable to fully extend the elbow. This provides information about the degree of bone involvement and the relationship of the forearm to the arm (Fig. 25-1). If plain radiographs fail to provide enough detail regarding bone loss, more detailed information can be obtained with a preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is typically not necessary in the evaluation of patients with inflammatory arthritis. However, in rare circumstances an MRI can provide information on the soft tissues of the elbow, particularly the collateral ligaments and the presence and degree of synovitis.

TREATMENT

Nonoperative Treatment

Rheumatoid arthritis, once diagnosed, is a chronic disease that stays with the patient until their death. As a consequence the surgeon is only one part of a large management team. Of equal importance is the rheumatologist, who looks after the patient’s systemic and generalized arthritis. A good working relationship between the orthopedic surgeon and the rheumatologist facilitates management decisions.

Patient education and understanding are paramount because a modification in work practice and lifestyle is often necessary. The involvement of therapists, both occupational and physical, is also useful.

Patient education and understanding are paramount because a modification in work practice and lifestyle is often necessary. The involvement of therapists, both occupational and physical, is also useful.

Figure 25-1 A: Anteroposterior and B: lateral radiographs demonstrating significant bone loss. Note the relationship of the humerus to the ulna. |

A discussion of the medical treatment of inflammatory arthritis lies outside the scope of this chapter. There are any number of drugs available, including nonsteroidal antiin-flammatory agents, corticosteroids, and various immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate, D-penicillamine, and gold. More recent advances include more specific medication aimed at the inflammatory pathway.

In addition to medication, the use of resting splints in a functional position at night or during disease flares can be of benefit. The normal functional position is with the elbow at 90 degrees and the forearm in neutral. At the same time the use of intraarticular steroid injections can also bring significant short-term benefit. In remission, mobilization within the limits of pain is encouraged.

Operative Treatment

It should be remembered that although arthroplasty is well established for the treatment of the later stages of an inflammatory arthritis, other treatment options, most specifically synovectomy, have a place in the earlier stages (2,3) The principal indications for synovectomy are patients with Larsen Stage 1 or 2 involvement whose symptoms cannot be controlled by nonsurgical means.

Open synovectomy usually is performed through a lateral approach and in combination with excision of the radial head (4,5). Resection of the radial head improves visualization of the joint, yet the synovectomy, particularly of the medial compartment of the joint, is often incomplete. Despite these potential shortcomings, open synovectomy has undoubtedly been of significant value to patients predominately with radial-sided elbow involvement. Woods and colleagues (6) compared this procedure with total elbow replacement. They were able to show that despite initial little difference in outcome, ultimately total elbow replacement proved more reliable with regard to pain relief and range of motion. They felt that radial head excision and synovectomy still had a role in younger patients or in those whose symptoms were related mainly to the radiohumeral joint. There have also been reports of open synovectomy for advanced stages of rheumatoid arthritis with some success (7). There is, however, some concern that synovectomy and radial head excision ultimately have an adverse effect on subsequent total elbow arthroplasty, particularly unlinked arthroplasty (8,9).

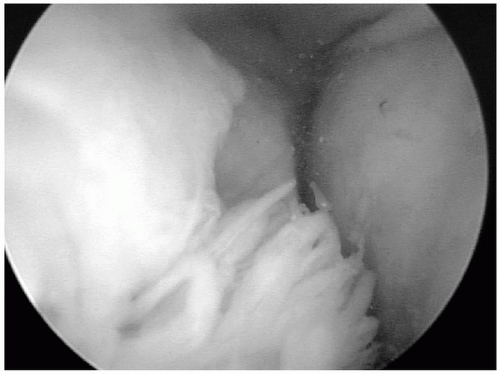

More recently, arthroscopic techniques have been described for elbow synovectomy. Arthroscopic synovectomy has the advantage of providing more complete visualization of the joint allowing for a more complete synovectomy. Lee and Morrey (10) reported their short- to medium-term results of 14 arthroscopic synovectomies in 11 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Initially they reported an excellent or good result, which deteriorated by 42 months. Four patients ultimately required total elbow replacements. Horiuchi and colleagues (11) also reported that arthroscopic synovectomy could alleviate pain. The best results were obtained in the early stages of the disease. I have undertaken arthroscopic synovectomy for inflammatory arthritis for several years using both medial and lateral portals to gain access to the anterior and posterior compartments of the elbow. In conjunction with a fluid management system and powered shavers, it is often possible to undertake a significant, indeed almost complete, synovectomy. At the same time bony parts of the joint can be removed (e.g., the radial head and tip of the olecranon) (Fig. 25-2).

IMPLANT CHOICES

There are essentially two basic types of elbow prosthesis: implants that have a specific linkage or hinge (linked implants) and those that have none (unlinked implants) (Table 25-2). The implants themselves are made out of conventional materials of stainless steel, cobalt chrome, or titanium with high-density polyethylene. Linked implants are joined by some form of sloppy “hinge,” which allows slight movement in the varus-valgus and axial plane. The unlinked implants consist of separate ulnar and humeral components and have no such linkage. They depend on the soft-tissue envelope, particularly the collateral ligaments, to maintain stability.

The linked designs evolved from rigid hinges, which reported significantly high rates of loosening. The linkage was made “sloppy” to allow a few degrees of varus-valgus and axial rotation to reduce stress on the bone cement interface and more closely mirror normal kinematics. The

humeral and ulnar components are stemmed and are generally fixed to bone with polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. Additional stability against posterior and rotational forces is gained by supracondylar fins or an anterior flange.

humeral and ulnar components are stemmed and are generally fixed to bone with polymethylmethacrylate bone cement. Additional stability against posterior and rotational forces is gained by supracondylar fins or an anterior flange.

TABLE 25-2 TYPES OF ELBOW PROSTHESES | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree