Arthroplasty for Posttraumatic Conditions of the Elbow

Matthew L. Ramsey

DEFINITION

Posttraumatic conditions of the elbow represent a variety of disorders involving the elbow as a result of previous injury. Included among the posttraumatic conditions are as follows:

Posttraumatic arthritis

Primary pathology involves posttraumatic degeneration of the articular surface.

Secondary pathologies can include contracture, loose bodies, and heterotopic bone.

Nonunion of the distal humerus

Present with different amounts of bone loss and instability through the nonunion

Often results from inadequate internal fixation of distal humerus fractures and typically occurs in the supracondylar region

Total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) is considered when reconstruction of the nonunion is deemed impossible or undesirable.

Dysfunctional instability of the elbow

Chronic instability (dislocation)

Chronic ligamentous instability of the elbow can lead to progressive articular cartilage degeneration and subchondral bone loss, particularly in the elderly, osteopenic patient.

Treatment for posttraumatic conditions is individualized, depending on the underlying pathology as well as the functional demands and age of the patient.

ANATOMY

The anatomy in posttraumatic conditions can vary widely. The integrity of the bone stock of the distal humerus, proximal ulna, and radial head must be evaluated. In addition, the soft tissue constraints that contribute to stability of the elbow need to be assessed.

Posttraumatic arthritis involving only the articular surface maintains the integrity of the regional architecture of the joint. There may be associated soft tissue contracture leading to functional limitation.

Nonunion of the distal humerus results in variable deformity. More severe deformity can result in loss of overall alignment of the arm with associated soft tissue contracture.

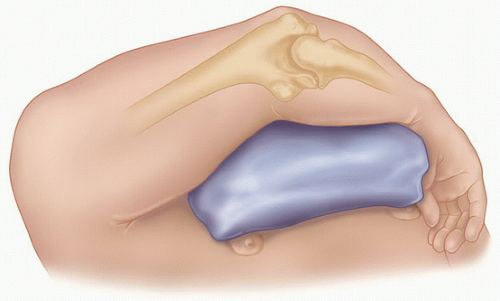

Dysfunctional instability of the elbow typically results from nonunion of the distal humerus, traumatic bone loss, or surgical excision of variable portions of the distal humerus. By definition, the anatomic relationship of the elbow is disrupted, resulting in dynamic or static dissociation of the forearm from the brachium (FIG 2).

FIG 2 • Photograph of a patient with dysfunctional instability of the elbow. Notice the prominent distal humerus and proximal migration of the forearm medial to the distal humerus.

Chronic instability of the elbow can result from a persistently unstable elbow following dislocation with or without associated fracture. The articular surface is compromised by the initial injury or persistent instability.

PATHOGENESIS

The common pathogenesis of all posttraumatic conditions is an injury to the elbow that compromises the integrity of the articular surface with or without nonarticular involvement of the humerus, ulna, or radius.

The articular surface can be directly injured by trauma or can degenerate over time as a result of a remote traumatic event.

Periarticular trauma and hemorrhage involving the capsule and musculotendinous tissues about the elbow can lead to intra-articular and periarticular fibrosis leading to intrinsic and extrinsic stiffness of the elbow.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patient History

The patient history is directed at gaining information about the initial injury, treatments undertaken, complications of treatment, presenting complaints, and patient expectations.

Detailed investigation of the patient’s symptoms should include questions regarding the degree of pain, presence of instability or stiffness, and mechanical symptoms of catching or locking.

Physical Examination

Inspection of the elbow

Presence and location of previous skin incisions or persistent wounds

Alignment of the extremity at rest and with attempted motion

Prominent hardware

Range of motion

Active range of motion (AROM) is assessed and compared to the opposite side. The degree of motion, smoothness of motion, and feel of the end point is established.

Passive range of motion (PROM) is then assessed and compared to the active motion arc.

Palpation of the elbow should systematically review all of the bony and soft tissue structures of the elbow.

Neurovascular examination should carefully assess motor and sensory function of the extremity.

The ulnar nerve needs to be carefully assessed. If previously surgically manipulated, its location should be identified if possible.

A functional requirement for consideration of TEA is functional elbow flexion (biceps and brachialis muscles). Functional extension (triceps muscle) is less critical than active flexion but should be carefully assessed.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain X-rays

Orthogonal views of the elbow are required (FIG 3).

A good lateral radiograph can usually be obtained except in cases of severe deformity.

If there is a significant flexion contracture, it can be difficult to obtain a useful anteroposterior (AP) radiograph. Inability to obtain a proper AP radiograph will typically result in overestimating the amount of joint destruction.

Oblique radiographs supplement the AP and lateral images.

Advanced Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) scan

CT scans are particularly helpful in assessing the structural integrity of the humerus, radius, and ulna.

Identifying the presence of periarticular deformity and the integrity of the articulations are facilitated by CT scan.

Three-dimensional reconstructions provide a better understanding of any deformity.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI is rarely needed in the assessment of a posttraumatic joint.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Nonunion/malunion of the distal humerus

Posttraumatic stiffness of the elbow

Chronic dislocation of the elbow

Traumatic bone loss or surgical excision of bone leading to instability

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

The success of nonoperative management depends on specific features of the pathology and the motivation and goals of the patient.

Activity modification attempts to reduce the forces across the elbow.

Overly aggressive attempts to maintain range of motion of the elbow, although commendable, can cause inflammation that is counterproductive to improved motion.

External bracing is occasionally used to support an unstable extremity. However, in general, bracing is poorly tolerated and functionally limiting.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management is directed at addressing the underlying cause of disability, taking into consideration the patient’s age, physical requirements, and expectations.

Total Elbow Replacement

Patients with posttraumatic conditions of the elbow tend to be younger than other patients undergoing TEA.4,5,6,11,14,15,17

In this group of patients, TEA should be considered in patients who

Have failed appropriate nonoperative management

Are not an appropriate candidate for other surgical options

Are willing to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle

Have no absolute contraindications to the procedure

Preoperative Planning

Implant Selection

Implants are described in terms of their physical linkage (linked, unlinked, or linkable) and on their constraint (constrained, semiconstrained, minimally constrained).

Linkage is determined by whether the components are physically joined.

Constraint is a more poorly defined quality of an implant. It depends on the geometry of the implant and its interaction with stabilizing soft tissues about the elbow.8

Linked (semiconstrained) designs

Linked implants have the advantage of being universally applicable to all posttraumatic conditions of the elbow.

Unlinked designs

The requirement for the use of unlinked designs in posttraumatic conditions of the elbow is integrity of the collateral ligaments and limited deformity such that normal anatomic relationships can be reestablished.

Linkable designs

Linkable designs have been developed to take advantage of the features of an unlinked implant while capturing the universal applicability of the linked implants. They can be converted from unlinked to linked either at the time of an initial surgery if stability cannot be conferred or remotely if instability becomes an issue postoperatively.

Positioning

Patients are placed supine on the operating table with a bump under the ipsilateral shoulder. The arm should be freely mobile through the shoulder to allow manipulation of the joint throughout surgery. The arm can then be placed across the body on a bump or externally rotated through the shoulder and flexed at the elbow (FIG 4).

TECHNIQUES

▪ Surgical Approach

A straight posterior skin incision placed off of the medial aspect of the olecranon is preferred. Previous incisions may modify the location of the incision. Regardless of the incision used, deep access to the medial and lateral aspect of the joint is required.

The ulnar nerve is identified. If not previously transposed, the nerve is transposed anteriorly. If the nerve was previously transposed, it only needs to be identified but not formally dissected unless the position of the nerve places it at risk during surgery.

▪ Triceps Management

Triceps-reflecting approaches are preferred over triceps-sparing approaches for posttraumatic conditions. Posttraumatic scarring and deformity can make a triceps-sparing approach difficult unless a nonunited distal humeral segment is to be resected.

A Bryan-Morrey approach is typically performed12 (TECH FIG 1). The medial aspect of the triceps is developed proximally, whereas the interval between the anconeus and flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) is developed distal to the olecranon. The triceps is reflected from medially to laterally in continuity with the anconeus. Release of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and medial collateral ligament (MCL) completes the exposure and allows separation of the ulna from the humerus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree