Arthrocentesis, Intra-Articular Injection, and Synovial Fluid Analysis

Jessica R. Berman

Theodore R. Fields

Richard Stern

Aspiration of a joint should always be performed on an initial evaluation or whenever a diagnosis is in doubt or in the case of monoarticular arthritis when infection must be excluded.

The fluid aspirated should always be analyzed for cell count, Gram stain, culture, and the presence of crystals at a minimum.

A known diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, gout or pseudogout does not exclude infection especially when one joint is disproportionately affected.

Arthrocentesis, or aspiration of fluid from a joint, is a safe and relatively easy procedure that plays both diagnostic and therapeutic roles in the management of arthritis. It should be included in the initial evaluation of every patient with a joint effusion, especially those with monarthritis.

Synovial fluid analysis following aspiration may help in differentiating a primary inflammatory process such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) from a noninflammatory process such as osteoarthritis. It can provide a specific diagnosis in crystalline arthritis.

Diagnostic indications

As part of an initial evaluation.

To rule out infection or hemorrhage.

To rule out crystalline disease.

Therapeutic indications

Drainage of an effusion to relieve pain and restore range of motion.

Instillation of medication (e.g., steroids and viscosupplementation).

Drainage of a septic joint.

Drainage of a hemarthrosis.

Absolute contraindications. Infection in overlying skin or surrounding soft tissue.

Relative contraindications. Coagulation disorder, especially if severe.

Intra-articular injection is primarily used to deliver intra-articular corticosteroids to treat inflamed joints (a similar technique is employed for injection of inflamed soft-tissues such as bursae or tendons). Contraindications are the same as for arthrocentesis. Corticosteroids should not be injected into a joint until infection has been excluded. In general, joints should not be injected more than three to four times per year. Injection of corticosteroids directly into a tendon or tendon insertion can sometimes result in tendon rupture.

I. MATERIALS FOR ASEPTIC SKIN PREPARATION

Sterile gloves.

Iodine solution.

Alcohol solution.

Sterile gauze pads.

II. MATERIALS FOR LOCAL ANESTHESIA

One percent lidocaine for skin, subcutaneous tissues, and joint structures.

Ethyl chloride spray for skin.

Table 8-1 Intra-articular Therapy Regimens

Joint

Needle gauge

Dose of methylprednisolone acetate (mg)

Knee, shoulder

16–24

40–80

Wrist, ankle, elbow

20–25

10–40

Interphalangeal

25–30

5–10

III. NEEDLES

Sterile 18- to 25-gauge needles, depending on the size of the joint. Inflamed joint fluids may be thick and may require a large-bore needle for removal. Sterile 30-gauge needles may be used for local anesthetic instillation, and for injection into small joints such as the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints and when no fluid aspiration is anticipated.

IV. SYRINGES

The size varies from 1 to 50 mL depending on the joint and amount of effusion.

V. TUBES FOR SYNOVIAL FLUID ANALYSIS

Hematology tube for cell count and differential.

Sterile tubes for Gram stain, cultures, and smears.

Heparinized tube for crystal analysis. Powdered anticoagulant may interfere with crystal identification.

Cytology bottle (if neoplasm is suspected).

VI. INTRA-ARTICULAR MEDICATIONS

At the Hospital for Special Surgery, methylprednisolone acetate (Depomedrol), a long-acting, insoluble corticosteroid preparation is used. The dose varies with the size of the joint. Betamethasone (Celestone) may be used when the goal is avoidance of a joint flare reaction and a shorter 2- to 4-week duration of action is acceptable (e.g., with attacks of crystal disease). Doses and appropriate needle sizes are summarized in Table 8-1.

The most important maneuver before aspirating a joint is to locate the appropriate landmark. This can best be done by making a skin impression with the round end of an unopened pen point or pen mark. Local anesthesia of the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissues is recommended. As a general rule, if it is important to obtain fluid for diagnostic purposes, a larger needle should be used (so as to avoid the need for reaspiration if the fluid is too thick to be aspirated by a small needle).

I. SHOULDER

The shoulder can be entered either anteriorly or posteriorly.

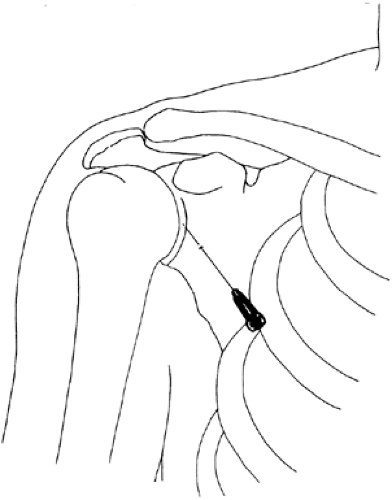

Anterior approach (Fig. 8-1). With the patient’s hand on the lap and with the shoulder muscles relaxed, the glenohumeral joint can be palpated by placing the fingers between the coracoid process and the humeral head. As the shoulder is internally rotated, the humeral head can be felt turning inward and the joint space can be felt as a groove just lateral to the coracoid process. When the skin over this area is anesthetized, a 20- or 22-gauge needle can be inserted lateral to the coracoid (the thoracoacromial artery lies medial to the coracoid). The needle is directed dorsally and medially into the joint space. The needle should be directed slightly superiorly to avoid the neurovascular bundle.

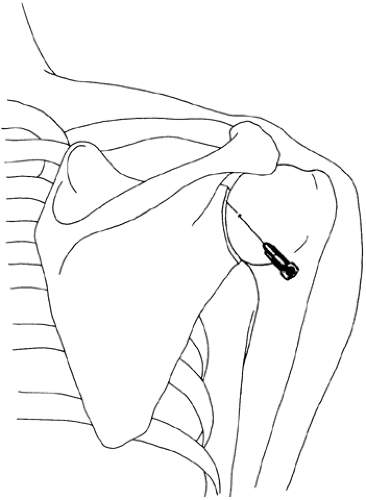

Posterior approach (Fig. 8-2). The posterior aspect of the shoulder joint is identified with the patient’s arm internally rotated maximally. This position is achieved by placing the patient’s ipsilateral hand on the opposite shoulder. The humeral head can then be palpated by placing a finger posteriorly along the acromion while the shoulder is rotated. A 20- or 22-gauge needle is inserted approximately 1 cm inferior to the posterior tip of the acromion and directed anteriorly and medially.

II. ELBOW

The elbow joint (Fig. 8-3) can be identified by placing the patient’s relaxed arm on the lap. With the palm facing the patient, the elbow is flexed to a 45-degree angle. By placing the finger on the lateral epicondyle, the shallow depression distal to it can be noted, which represents the elbow joint. A 22-gauge needle is introduced perpendicular to the joint.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree