Essential Features

- Most patients with acute low back pain improve spontaneously within 4 weeks.

- Degenerative change in the lumbar spine is the most commonly identified cause of low back pain.

- Diagnostic testing is rarely indicated in the absence of significant neurologic involvement or suspicion of systemic disease unless symptoms persist beyond 4 weeks.

- Imaging abnormalities must be interpreted carefully because they are frequently seen in asymptomatic persons.

- Patients with neurologic involvement or an underlying systemic disease (eg, infections, malignancies, and spondyloarthropathies) may need urgent or specific treatment, including surgery.

- Surgery is rarely needed for patients who respond to analgesia, education, aerobic conditioning, and physical therapy.

General Considerations

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common musculoskeletal complaint and a leading cause of work disability. An estimated 80% of the population experiences it during their lifetime.

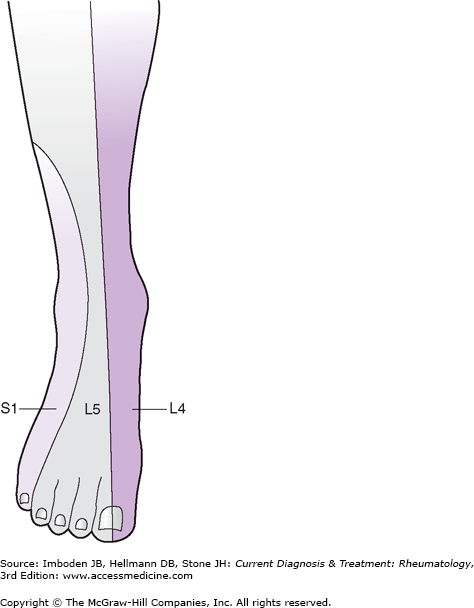

LBP affects the area between the lower rib cage and gluteal folds and frequently radiates into the thighs. Most LBP is benign and self-limited. Ninety percent of patients with acute LBP improve spontaneously within 4 weeks, although low-grade symptoms may persist in some. Approximately half of the patients with acute LBP experience one or more episodes of LBP over the next few years, but these, too, are generally self-limited. Less than 1% of the patients with acute LBP have true sciatica, which is defined as pain in the distribution of a lumbar nerve root, often accompanied by sensory and motor deficits (Table 10–1 and Figure 10–1).

| Disk Herniation | Nerve Root | Motor | Sensory (Light Touch) | Reflex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L3–4 | L4 | Dorsiflexion of foot | Medial foot | Knee |

| L4–5 | L5 | Dorsiflexion of great toe | Dorsal foot | None |

| L5–S1 | S1 | Plantar flexion of foot | Lateral foot | Ankle |

Clinical Findings

An important aspect of history-taking in a patient with LBP is the identification of “red flags” to ensure that conditions that require early diagnostic testing are not missed (Table 10–2).

|

Mechanical LBP is due to an anatomic or functional abnormality that is not associated with inflammatory or neoplastic disease. Mechanical LBP increases with physical activity and upright posture and is relieved by rest and recumbency. Degenerative change in the lumbar spine is the most common cause of mechanical LBP. Severe and acute mechanical LBP in a slender and elderly woman is suspicious for a vertebral compression fracture secondary to osteoporosis. Nonmechanical LBP, especially when accompanied by nocturnal pain, suggests the possibility of underlying infection or neoplasm.

Inflammatory LBP, as seen in the spondyloarthropathies, typically worsens with rest, improves with activity, and is accompanied by morning stiffness that lasts half an hour or longer. Some patients complain of alternating buttock pain. Sciatica and pseudoclaudication suggest neurologic involvement. Sciatica results from nerve root compression, generally from a herniated disk, and produces lancinating pain in a radicular distribution. Sciatica should be differentiated from nonneurogenic sclerotomal pain, which arises from pathology within the disk, facet joint, or lumbar paraspinal muscles and ligaments. Like sciatica, sclerotomal pain is often referred into the lower extremities, but unlike sciatica, sclerotomal pain is nondermatomal in distribution, is dull in quality, and pain usually does not radiate below the knee or have associated paresthesias.

Persistence of LBP may be associated with depression, job dissatisfaction, and pursuit of disability compensation or litigation.

Examination of the back usually does not lead to a specific diagnosis. A general physical examination, including a neurologic examination, may help identify those few patients who have a systemic disease or neurologic involvement.

Inspection may reveal the presence of scoliosis. Scoliosis can be either structural or functional. A structural scoliosis is associated with structural changes of the vertebral column and sometimes the rib cage as well. In adults, structural scoliosis is usually secondary to degenerative changes, although some individuals have a history of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. As the patient bends forward (flexing the spine), structural scoliosis persists whereas functional scoliosis usually disappears. Paravertebral muscle spasm and leg length discrepancy are leading causes of functional scoliosis. Palpation can detect paravertebral muscle spasm that often leads to loss of the normal lumbar lordosis. Point tenderness over the spine has sensitivity but not specificity for vertebral osteomyelitis. A palpable step-off between adjacent spinous processes indicates spondylolisthesis.

Limited spinal motion (flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation) is not associated with any specific diagnosis, since LBP due to any cause may limit motion. Range-of-motion measurements, however, can help in monitoring treatment.

The hip joints should be examined for any decrease in range of motion because hip arthritis, which normally causes groin pain, may occasionally present as LBP. Tenderness over the greater trochanter of the hip is seen in trochanteric bursitis, which can be confused with LBP. The presence of more widespread tender points suggests the possibility that LBP may be secondary to fibromyalgia.

A straight-leg raising test should be performed on all patients with sciatica or pseudoclaudication. Straight leg raising places tension on the sciatic nerve and thereby stretches the sciatic nerve roots (L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3). If any of these nerve roots is already irritated, such as by impingement from a herniated disk, further tension on the nerve root by straight-leg raising will result in radicular pain that extends below the knee. The test is done by the examiner cupping the patient’s heel in his or her hand and flexing the hip while keeping the knee extended. The test is positive if radicular pain (not merely back or hamstring pain) is produced when the leg is raised less than 60 degrees. The straight-leg raising test is very sensitive (95%) but not specific (40%) for clinically significant disk herniation at the L4–5 or L5–S1 level, which are the sites of 95% of clinically meaningful disk herniations. False-negative tests are seen more frequently with herniation above the L4–5 level. The straight-leg raising test is usually negative in patients with spinal stenosis. The crossed straight-leg raising test (with sciatica reproduced when the opposite leg is raised) is insensitive (25%) but highly specific (90%) for disk herniation.

The neurologic examination (see Table 10–1) should always include motor testing with focus on dorsiflexion of the ankle (L4), great toe dorsiflexion (L5), and foot plantar flexion (S1); determination of knee (L4) and ankle (S1) deep tendon reflexes; and tests for dermatomal sensory loss (see Figure 10–1). The inability to toe walk (mostly S1) and heel walk (mostly L5) may indicate muscle weakness. Muscle atrophy can be detected by circumferential measurements of the calf and thigh at the same level bilaterally.

Laboratory studies play a minor role in the investigation of LBP. They are used mostly in identifying patients with systemic causes of LBP. A patient with normal blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and radiographs of the lumbar spine is unlikely to have an underlying systemic disease as the cause of LBP.

Diagnostic tests should be done early for patients who have evidence of a major or progressive neurologic deficit and those in whom an underlying systemic disease is suspected (see Table 10–2). Otherwise, diagnostic tests are not required unless symptoms persist for more than 4 weeks. Because 90% of patients with LBP recover spontaneously within 4 weeks, this approach avoids unnecessary early testing.

A major problem with imaging studies is that many of the anatomic abnormalities seen are common in asymptomatic persons. These abnormalities are often the result of age-related degenerative changes and are frequently present after the age of 30. Making causal inferences based on imaging abnormalities can be hazardous in the absence of corresponding clinical findings and can lead to unnecessary and costly interventions with a potential for iatrogenic complications.

Plain radiographs of the spine do not usually help in determining the cause of LBP. Abnormalities such as single disk degeneration, facet joint degeneration, Schmorl nodes (intraspongy disk herniation), spondylolysis, mild spondylolisthesis, transitional vertebrae (lumbarization of S1 or sacralization of L5), spina bifida occulta, and mild scoliosis are equally prevalent in persons with and without LBP. Plain radiography should be limited to patients with clinical findings suggestive of infection, cancer, spondyloarthritis, or trauma, or those who continue to have LBP after 4–6 weeks of conservative care. It is noteworthy that radiation exposure to the female gonads from standard views of the lumbar spine is equivalent to that of a daily chest radiograph for several years.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be reserved for patients in whom there is a strong clinical indication of underlying infection or cancer, or for the evaluation of patients with significant or progressive neurologic deficits. MRI is the preferred modality for the detection of spinal infection and cancers, herniated disks, and spinal stenosis. When interpreting the results of MRI and CT, it is important to remember that most asymptomatic adults above age 30 have evidence of either disk bulges (symmetric, circumferential extension of the disk material beyond the interspace) or disk herniation (focal or asymmetric extension of the disk bulge). Herniations are classified according to whether they are protrusions or extrusions. Protrusions are broad-based but extrusions have a neck, so that the base of an extrusion is narrower than the extruded material. Bulges and protrusions are common in asymptomatic adults. Thus, when these findings are seen in a patient, they are not necessarily the cause of LBP. Extrusions are less common but are also not invariably symptomatic. MRI with the intravenous contrast agent gadolinium is useful for the evaluation of patients with prior lumbar spine surgery (with no hardware present) to help in the differentiation of scar tissue from recurrent disk herniation.

The significance of a focal high signal (high-intensity zone) in the posterior annulus on a T2-weighted image is controversial. It is thought to represent annular tears and to correlate with positive findings on provocative diskography (which itself is a controversial procedure). Discogenic LBP has been diagnosed in patients with these high-intensity zones, and spinal fusion surgery is often recommended. The high prevalence of high-intensity zones in asymptomatic individuals, however, calls this approach into question.

Bone scanning is used primarily to detect infection, bony metastases, and occult fractures. Bone scans have limited specificity due to poor spatial resolution, and thus abnormal findings often require confirmatory imaging, such as MRI.

Electrodiagnostic studies can confirm nerve root compression and define the distribution and severity of involvement. Nerve conduction studies and electromyography are unnecessary when a patient has an obvious radiculopathy or isolated LBP. Electrodiagnosis, however, may be helpful in differentiating the limb pain of peroneal nerve palsy from that of L5 radiculopathy or in evaluating possible factitious weakness. Electromyographic changes depend on the development of muscle denervation following nerve injury and may not be detected until a few weeks after the injury.

Differential Diagnosis

LBP usually originates from the lumbar spine or associated muscles and ligaments (Table 10–3). Rarely, pain is referred to the back from visceral disease. More than 95% of LBP is mechanical (Table 10–4). Degenerative change, also called lumbar spondylosis or lumbar osteoarthritis, is by far the most common disorder seen within the spine and the most important cause of mechanical LBP. However, even when one is certain that the cause of LBP is lumbar spondylosis, identification of the “pain generator” is challenging. The precise disk(s) or facet joint(s) responsible for the patient’s pain is difficult to localize.

The focus of the initial diagnostic evaluation is to identify the small proportion of patients with systemic disease (infection, neoplasm, and spondyloarthropathy together account for only 1% of patients with LBP) or with neurologic involvement that requires urgent or specific intervention.

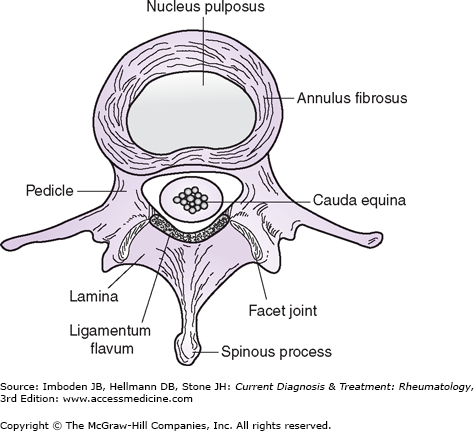

Lumbar spondylosis, or osteoarthritis of the lumbar spine, is the most commonly identified cause of LBP. Degenerative changes occur in both the intervertebral disk and facet joints (Figure 10–2), predisposing patients to disk herniation, spondylisthesis, and spinal stenosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree