Essential Features

- A thorough clinical history and a detailed physical examination are essential to delineate various intrinsic and extrinsic causes of pain in patients with hip and knee total joint replacements.

- Radiographs with orthogonal and weight-bearing views should be ordered to assess signs of implant-related complications.

- Laboratory investigations should include both erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) as screening serologic markers for joint infection.

- A high index of suspicion for infection must always be maintained, especially in patients with comorbidities such as diabetes, inflammatory arthritis, and compromised immunity.

- Awareness of adverse soft-tissue reaction to metal wear debris in patients with painful metal-on-metal total hip replacements is important in light of its increasing use in young and active patients.

General Considerations

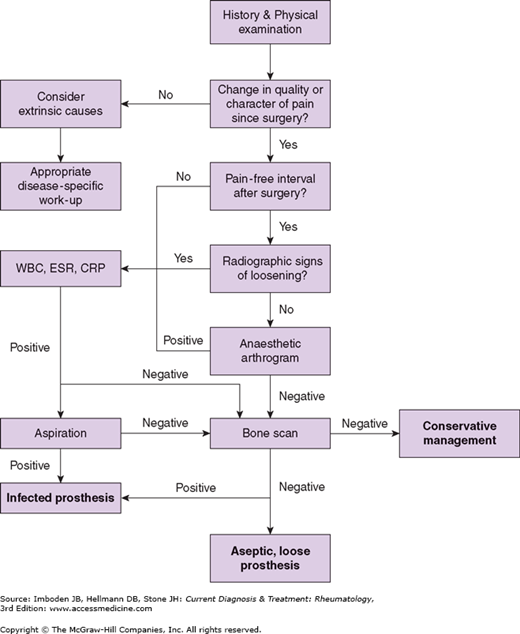

Total hip and knee joint replacement surgery is one of the most successful operations in medicine in terms of patient satisfaction, reduction in pain, and improvement in function. Despite the overwhelming success of total joint arthroplasty, the painful hip and knee prosthetic joint remains a challenge for the physician to evaluate and manage. Because a painful prosthetic hip and knee joint has various intrinsic and extrinsic causes (Table 13–1), a thorough clinical history, a detailed physical examination, as well as radiographic and laboratory tests are essential to delineate the potential causes of the pain (Figure 13–1).

|

Clinical Findings

A complete history is critical in the evaluation of patients with painful hip and knee replacements. The temporal onset, duration, severity, location, and character of the pain help narrow the differential diagnosis. The presence of pain since surgery suggests either infection, failure to obtain initial implant stability, a periprosthetic fracture, or a misdiagnosis of the initial reason the arthroplasty was performed. If the pain comes after a pain-free interval following surgery, the likely causes include aseptic loosening or late infection.

Activity-related pain that is relieved with rest suggests implant loosening, fracture, or either neurogenic or vascular claudication. The presence of persistent pain, pain at rest, or night pain may indicate sepsis or malignancy.

Precipitating causes of the pain should be elucidated. Onset of pain after trauma may be caused by fracture or loosening. A history of delayed wound healing, chronic drainage, postoperative hematoma formation, pain after dental or gastrointestinal procedures, and distant sites of infection are all clues to potential joint sepsis. Risk factors that increase likelihood for infection include immunosuppression, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and inflammatory arthritis.

After a general examination, evaluation of a painful prosthetic joint should focus on the joints above and below the prosthesis, and the spine. A comprehensive neurovascular examination is necessary to rule out neurogenic and vascular causes of pain. When examining the lower extremity, gait should be observed for antalgia, limb-length discrepancy, and Trendelenburg lurch. Because lumbar spine disease and fixed pelvic obliquity may be present, true and apparent leg lengths should also be assessed.

Inspection of the skin should note previous scars and signs of infection, including warmth, erythema, fluctuance, drainage, and sinus tracts. Range of motion (ROM) should be examined to determine the positions that elicit the patient’s pain. Pain with active ROM or with extremes of motion often indicate loosening, while pain with passive ROM suggests infection.

In addition to radiographic studies, laboratory tests such as the complete blood count and differential, ESR, and CRP can provide additional information in evaluating the painful prosthetic joint.

The ESR can help distinguish septic from aseptic loosening after joint replacement surgery. However, the ESR typically increases to a peak at 5–7 days postoperatively and then declines gradually to its preoperative baseline level over a 3-month period. In some patients, the ESR remains elevated for up to 1 year after surgery.

The CRP has been reported to be a better marker for infection than ESR. When ESR and CRP levels are measured together as a screening battery, the sensitivity is 95%, and the negative predictive value is 97%. When both the ESR and CRP are elevated, specificity for infection has been reported to be as high as 93%. Conversely, if both ESR and CRP are within normal limits, the diagnosis of infection can be excluded.

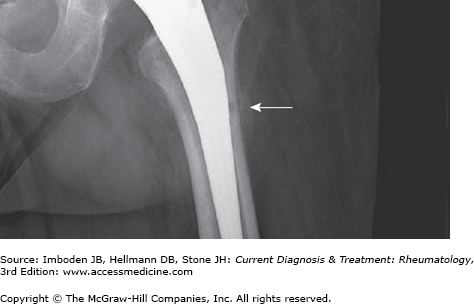

After a complete history is obtained and a physical examination is performed, serial plain radiographs should be obtained to look for signs of implant-related complications, such as loosening, migration, or osteolysis. Signs of implant loosening include a progressive increase in the radiolucent line, change in component position and subsidence, fracture of the cement mantle, or bony reaction around the tip of the component. There are also certain radiographic findings suggestive of infection. These signs include periosteal new bone formation (Figure 13–2), endosteal scalloping, soft-tissue swelling, osteopenia, and premature loosening of the component.

Figure 13–2.

The periosteal reaction (arrow

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree