Approach to the Knee: Management Algorithm

Eric B. Smith

Jess H. Lonner

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Similar to all branches of medicine, the history of present illness is the most important diagnostic tool to identify causes of knee pain. Patient age, sex, and activity level/occupation are the first important pieces of information as certain conditions may be more likely to occur in one gender or age group than another, and treatment strategies may be impacted by age, expectations, degree of impairment, and preinjury activity level or occupation. Description of an acute traumatic event suggests fracture, bone contusion, cartilage damage, or tearing/disruption of a ligament, tendon, or meniscus. Insidious achy discomfort is more consistent with arthritis. If the patient recently began a new exercise activity or has been participating in a sporting activity for the first time, pain may be due to overuse (see Chapter 17). Severity, acuity, and duration of symptoms (i.e., ability to weight bear, amount of swelling) will dictate the urgency of further studies or referral to an emergency department or directly to an orthopaedic surgeon.

The location and quality of the pain should be considered, as these may suggest different conditions. For instance, a sharp, localized pain can point you directly to the anatomic source (e.g., patella fracture, tibial stress fracture, or meniscus tear), whereas diffuse achy pain may suggest a generalized process such as arthritis or gout. Vague complaints, not well localized to the knee, but that radiate up and down the thigh or entire limb may suggest an extrinsic source of the pain such as referred hip pain or lumbar radiculopathy. Night pain, pain at rest, or joint pain that is unrelated to activity or seems out of proportion to expectations should raise suspicion of infection, tumor, or other metabolic conditions.

Associated symptoms may further narrow the diagnosis. For example, instability may indicate a ligament or meniscal tear. Clicking and locking are common with meniscal tears. Grinding and stiffness are common with osteoarthritis. Fevers, chills, and night sweats are concerning for a septic joint. History of tick bite and rash (bull’s-eye) is typical for Lyme disease. Swelling is a common finding seen with many acute or chronic intra-articular knee problems (see Chapter 21). A gradual functional decline in an elderly patient’s ambulatory status is seen with arthritis.

Pertinent information from the patient’s past medical and surgical histories will also give clues to the diagnosis. For instance, patients presenting with an effusion and pain who have a history of degenerative or inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid, lupus, psoriatic, etc.) may be experiencing a flare; those with sickle cell disease or other coagulopathies, or who have used varied doses of oral or parenteral steroids, may have avascular necrosis of the knees or hips; a remote history of trauma or previous knee surgery leads one to consider posttraumatic

or secondary arthritis; and lastly, certain medications, such as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), may have musculoskeletal side effects such as muscle and joint pain.

or secondary arthritis; and lastly, certain medications, such as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), may have musculoskeletal side effects such as muscle and joint pain.

CLINICAL POINTS

There are many different etiologies of knee pain.

A detailed history and physical exam will often provide the diagnosis.

Confirm suspected diagnosis with additional studies.

Treatment may vary based on diagnosis, condition, patient age, or activity level.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

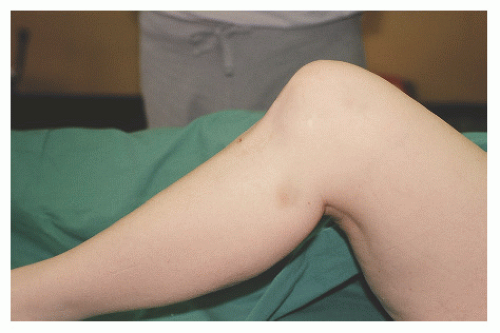

Physical examination of the patient starts with a gait analysis. If a patient can walk into the office without a limp or any difficulty, a structural problem within the knee is unlikely. Significant deformities, malalignment (genu varum—bowlegged deformity; genu valgum—knock-knee deformity), or a varus or valgus thrust should be noted as these findings could indicate patellar maltracking, ligament deficiency/instability, or severe arthritis. Assess the knee for evidence of an effusion, ecchymosis, skin integrity, and temperature changes (Fig. 14-1). These may also help narrow the diagnosis. Excoriating plaques on the extensor surfaces of the knees, elbows, back, and scalp suggest psoriatic arthritis. Take the knee through active and passive range of motion. Normal range of motion is approximately 0 to 135 degrees; however, there can be significant variability. Painless decreased range of motion may suggest arthritis, whereas diminished motion accompanied by severe pain may indicate significant intrinsic pathology, such as meniscus or ligament tears, fracture, and patellar instability. Someone who can achieve full passive extension, but cannot actively extend the knee may have disruption of the quadriceps or patellar tendons. A palpable defect may also be noted at the superior or inferior pole of the patella with tendon disruption. While ranging the knee, crepitus can be palpated (and often heard) with one hand resting on the patella indicating cartilage wear in the patellofemoral joint. Observe patellar tracking as the patient actively flexes and extends the knee. Subluxation or patellar instability may be evident.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree