Anterior/Posterior Cervical Approaches

Jonathan S. Erulkar

Jonathan N. Grauer

INTRODUCTION

Anterior and posterior cervical procedures are common for degenerative, traumatic, and oncologic pathologies. Such procedures entail a number of nuances that must be considered to maximize efficiency and avoid complications. These considerations will be reviewed in the following sections.

ANTERIOR/LATERAL CERVICAL APPROACHES

Several approaches have been developed for the anterior cervical region. The retropharyngeal, or Smith-Robinson, approach is clearly the workhorse approach for the anterior cervical spine. However, pathology and surgical goals should direct the approach taken. As such, it is important for the spine surgeon to be aware of this and alternate anterior cervical approaches. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is the divide between the anterior and lateral approaches that will be described below.

Patient Positioning for Anterior Approaches

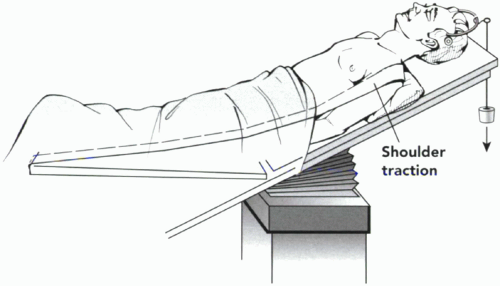

The patient is placed supine on the operating table (Fig. 1.1). A regular operating table is routinely used. The head and foot of the table may be reversed prior to the procedure to allow for better clearance of a fluoroscopy unit under the table. The patient is often partially flexed and the table placed into reverse-Trendelenburg to elevate the head and minimize venous engorgement.

The neck is then extended for most anterior procedures. Not only does this increase access, but it also helps achieve the lordosis desired from most reconstructive procedures. Removing pillows from behind the head and/or placing a bump in the interscapular region may accomplish slight cervical extension. Some advocate using an inflatable intravenous pressure bag for this purpose as its height can be easily adjusted. Additionally, the pelvis can be bumped to facilitate iliac crest harvest if this is to be used.

Some place the head in traction for anterior cervical procedures. Halter traction can be considered to stabilize the head but generally does not achieve significant cervical distraction. Additionally, this may limit access to the upper cervical spine. Alternatively, greater traction may be applied with Gardner-Wells tongs. Finally, if a halo is considered for postoperative care, the halo ring can be placed instead of tongs to allow for intraoperative traction. Another option for positioning is a horseshoe headrest to facilitate head positioning with or without traction.

The arms are tucked at the patient’s sides. This must be done in cooperation with anesthesia to ensure that appropriate access and monitoring are maintained. The shoulders are then pulled distally with traction in a caudal direction with tape to the end of the table. This allows better access to the cervical region and improved radiographic visualization. If the tape is run along the lateral aspects of the arms, this can also help sling the arms into a secure position. Excessive traction must be avoided to prevent brachial plexus injury.

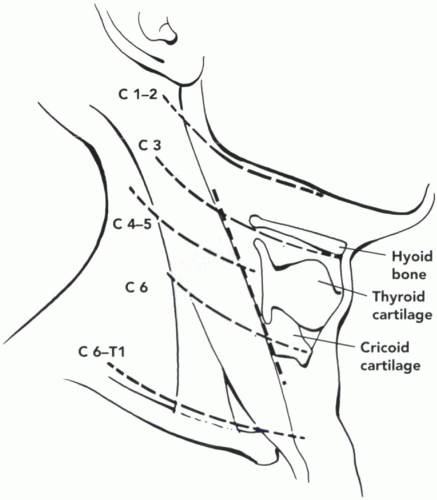

Superficial landmarks can assist in placement of the skin incision. These include the angle of the jaw (C1 to C2), the hyoid bone (C3), the thyroid cartilage (C4 to C5), the cricoid cartilage (C6), and the supraclavicular area (C7 to T1) (Fig. 1.2). Additionally, the carotid, or Cassuigne’s tubercle,

is the prominent lateral process of C6 that can often be palpated and used as a landmark both for determining placement of the skin incision as well as during the approach. Internally, focal osteophytes may correlate with known preoperative landmarks from imaging studies.

is the prominent lateral process of C6 that can often be palpated and used as a landmark both for determining placement of the skin incision as well as during the approach. Internally, focal osteophytes may correlate with known preoperative landmarks from imaging studies.

Prevention of neurological injury is of paramount importance with positioning. First, head extension can be checked prior to intubation for individual patients to determine how much extension can be safely achieved without inciting pain or eliciting a L’Hermitte’s sign. Especially in the setting of myelopathy, neurologic monitoring of long tracts may be considered before and after cervical extension to confirm the safety of head positioning. Upper extremity electromyelography can be monitored to rule out root/plexus traction injuries.

Anteromedial Approach to the Subaxial Cervical Spine

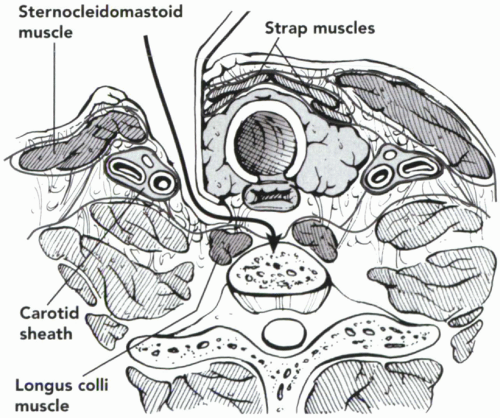

This is clearly the most commonly used approach to the anterior spine. Also referred to as the Smith-Robinson approach (1), this affords excellent and relatively extensile exposure to the mid- and lower cervical spine (Fig. 1.3).

The patient is positioned and level of incision determined as described above. Most commonly, a transverse incision is made in line with the skin creases for cosmetic appearance. Alternatively, if three or more levels require

exposure, an oblique incision may be considered along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid.

exposure, an oblique incision may be considered along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid.

Figure 1.3 The Smith-Robinson approach to the cervical spine. Note that the dissection path is medial to the sternocleidomastoid, the carotid sheath, and the longus coli muscle. |

The platysma can be divided vertically or horizontally. The subplatysmal plane should be developed below the investing fascia to maximize exposure, and the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid on the lateral side of the dissection and the strap muscles on the medial side of the dissection will be visualized.

Retraction of the sternocleidomastoid laterally and strap muscles medially will allow for division of the deep fascia and blunt dissection through the pretracheal fascia. As this plane is opened, the carotid artery should be palpated laterally from within its sheath. The trachea and esophagus lie medially. These surrounding structures should be well-respected.

Several traversing structures may be encountered during dissection and development of the interval. The omohyoid muscle courses from proximal medial to distal lateral attaching to the clavicle. This can be retracted or divided to facilitate exposure. The middle thyroid artery is often identified at approximately the C5 level, which may also be retracted or divided. The superior thyroid artery is encountered above C4. This should be respected, if possible, as it travels in close proximity to the superior laryngeal nerve. The inferior thyroid artery is seen below C6 and may be in proximity to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN).

The expected position of the RLN leads some to prefer a left-sided cervical approach despite the fact that a right-sided approach is more convenient for most right-handed surgeons. On the left, the RLN loops around the aorta and returns to the esophageal/tracheal groove early in its recurrent course. On the right, the RLN loops around the subclavian artery and is less predictable in its level of return to the esophageal/tracheal groove (2). Nevertheless, large series of cases have not found a significant difference in the rate of injury depending on the side of the approach for primary surgeries (3). Revision surgery, however, was associated with increased risk of injury to the RLN. As such, it is advisable to obtain preoperative laryngoscopic evaluation in patients with previous cervical surgery prior to revision procedures (4). If normal vocal cord function is observed, an approach from the opposite side is advocated to facilitate an easier dissection. If abnormal vocal cord function is observed, an approach from the same side as the index procedure is advocated to avoid potential injury to the remaining RLN.

In addition, duration of intubation, the size of the endotracheal (ET) tube, the area of ET tube contact with the trachea, and cuff pressure which is increased with retraction have all been associated with postoperative hoarseness and pain (5,6,7). As such, adjustments of cuff pressure with retraction and minimization of retraction time and pressure may be expected to reduce postoperative hoarseness.

After passing the level of the carotid sheath, blunt dissection easily exposes the prevertebral space and underlying cervical spine. The longus coli muscle can be elevated and retracted. A spinal needle is generally placed into the disc space or vertebral body and a lateral localizing film taken to confirm the level of dissection. With the levels of dissection localized, self-retaining retractors are generally placed.

Closure involves reapproximation of the platysma and skin. A drain is usually placed in the prevertebral space to avoid any potentially significant hematoma formation.

Anteromedial Approach to the Upper Cervical Spine

The anterior retropharyngeal approach is a superior extension of the Smith-Robinson approach described above (8,9). Approach to this level requires specific considerations, as discussed below.

Skin incision is made just below and in line with the angle of the mandible curving toward the mastoid. If exposure to C3 or below is needed, the skin incision should curve along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid in an S-curve shape. The dissection then proceeds through the platysma and superficial fascia. Some authors have suggested a mandible or tongue-splitting approach if needed to access very high cervical pathologies. However, such extensions should be used judiciously, given the increased morbidities.

There are a number of traversing neurovascular structures that should be respected during these high cervical approaches. Superficially are branches of the ansa cervicalis. As blunt dissection may proceed along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid, care must be taken to identify the hypoglossal nerve that can be retracted cephalad. The digastric muscle can be a helpful landmark in identifying the hypoglossal nerve — this can be retracted with the nerve or may be incised to provide greater exposure (Fig. 1.4). In addition, the superior thyroid artery and vein should be identified and retracted caudad.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree