Anterior Reconstruction for Instability in the Throwing Athlete

Richard J. Hawkins

John A. Zavala

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

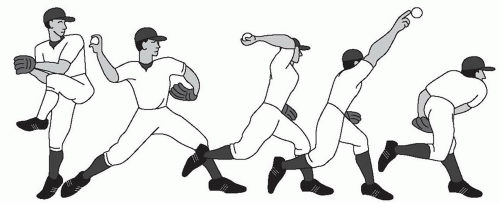

The throwing cycle is a kinetic chain that serves to transfer energy from the trunk and lower extremity to the throwing arm. The cycle is divided into five defined phases: windup, early cocking, late cocking, acceleration, and follow-through (Fig. 20-1) (1). In the throwing motion, the athlete must maximally accelerate and decelerate the arm over a short time period. Maximal angular velocities have been shown to be 7,000 degree/s and a torque of 52 Nm (2). Sabick et al demonstrate in professional pitchers a humeral torque of 92 Nm (3). The humeral head experiences an anterior translation force of 40% of body weight in the cocking phase and a distraction force of 80% of body weight with deceleration. The glenohumeral joint undergoes adaptive bony changes with throwers demonstrating increased humeral retrotorsion (5). Even minor pathologic changes that occur in the throwing shoulder can be debilitating for the thrower. A fine line exists between adaptive changes in the throwing shoulder and pathologic instability.

Increased anterior translation in the throwing shoulder may be defined as a pathologic increase in glenohumeral anterior translation that results in symptoms. Symptoms include pain and loss of velocity. Throwers have increased external rotation and decreased internal rotation in their throwing arm versus the contralateral arm (4, 5).

Pathology in the throwing shoulder is a result of alterations of the kinetic chain and secondary changes in scapulothoracic function. Kvitne and Jobe (6) described the pattern of recurrent, involuntary, microtraumatic, anterior subluxation. As a consequence of repetitive microtrauma, the shoulder develops anterior microinstability. In the presence of this anterior instability due to loss of static restraints, the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder compensate. Fatigue of the dynamic restraints leads to further stresses on the static restraints to anterior translation of the glenohumeral joint.

The anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament is the primary restraint to anterior translation in the abducted and externally rotated (ABER) position (7). This ligament can undergo significant attenuation that results in excessive anterior translation. The anterior forces seen in deceleration are significant, and in the presence of attenuated anterior static stabilizers, the posterior supraspinatus and infraspinatus become stabilizers to anterior translation. The anterior inferior aspect of the glenoid labrum plays a role in controlling anterior translation. For this reason, in the theory of anterior capsular laxity, the posterior supraspinatus and infraspinatus are common sites of injury in throwers.

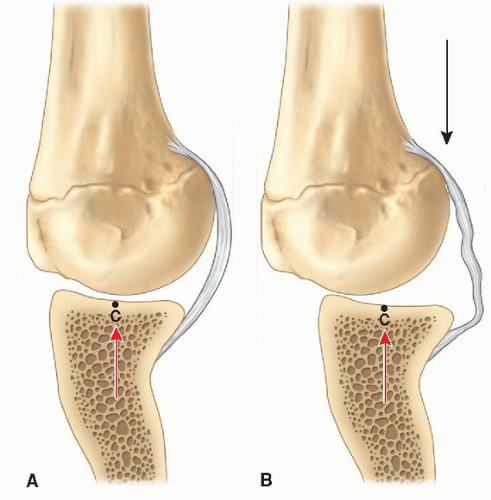

Burkhart et al. (8) have stated that the essential lesion is posterior capsular contracture from repetitive throwing in the setting of posterior muscle weakness and shoulder dysfunction. The posterior inferior glenohumeral ligament (PIGHL) contracts in the setting of repetitive trauma due to the excess distraction force at

follow-through seen in the setting of weakened posterior shoulder muscles. This results in an alteration of the glenohumeral joint contact point to a more posterosuperior position. The resultant change in position results in a relative “pseudolaxity” of the anterior capsule (Fig. 20-2). When a pathologic change in external rotation occurs, the biceps anchor experiences a more posteriorly directed force leading to peel-back lesions. This may also be due to repetitive normal increased external rotation. The rotator cuff experiences both tension and abrasion wear on the articular side due to internal impingement (8, 9, 10).

follow-through seen in the setting of weakened posterior shoulder muscles. This results in an alteration of the glenohumeral joint contact point to a more posterosuperior position. The resultant change in position results in a relative “pseudolaxity” of the anterior capsule (Fig. 20-2). When a pathologic change in external rotation occurs, the biceps anchor experiences a more posteriorly directed force leading to peel-back lesions. This may also be due to repetitive normal increased external rotation. The rotator cuff experiences both tension and abrasion wear on the articular side due to internal impingement (8, 9, 10).

While different theories exist regarding the pathology of anterior laxity seen in throwing shoulders, it is important to note that a continuum of pathology exists based on alterations in the kinetic chain and scapulothoracic function. When evaluating the throwing athlete, 80% of pathology will be related to internal impingement, superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) tears, and posterior capsular contracture. Excess anterior translation represents a continuum of pathology in the throwing shoulder. The response may be hyperangulation and excessive external rotation in the abducted position followed by increased anterior translation, leading to internal impingement, SLAP lesions and sometimes combined with posterior tightness.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The most important aspects of caring for the throwing athlete are the history and physical exam. The presentation of excessive anterior translation in the throwing athlete is far more subtle than in that of the nonthrower who usually has traumatic instability. Throwers will often present with complaints of decreased control, decreased velocity, “dead arm,” and pain (11). A history of subluxation or dislocation is almost never the presentation. A component of night pain, while rare, may signify a significant rotator cuff involvement. The thrower can sometimes localize the timing and localization of the pain in the throwing cycle. Posterior-based pain during cocking and early acceleration may suggest internal impingement or a SLAP tear (12). Anterior pain may be associated with injury to the subscapularis, biceps tendon, or anterior capsulolabral structures. Pain noted during follow-through when the humerus is in internal rotation and stress is placed on the posterior complex often signifies posterior capsulolabral and/or posterior cuff injury.

Examination typically may begin with the patient seated. First begin with inspection of the integumentary system and the musculature of the shoulder girdle to note any scars or soft-tissue asymmetry. Though rare, atrophy of the infraspinatus signifies suprascapular neuropathy. Range of motion should be performed comparing the athlete’s dominant and nondominant shoulder, consisting of forward elevation, external rotation with the arm adducted at the side, internal rotation relative to posterior spine landmarks, external rotation, and internal rotation at 90 degrees of abduction. While throwers will have increased external rotation and decreased internal rotation versus the nondominant arm, their total rotational arc should be symmetric. Greater than a 20-degree internal rotation deficit on the throwing shoulder versus the nonthrowing shoulder is suggestive of glenohumeral internal rotation deficit. Provocative tests such as Speed’s and Yergason’s might suggest biceps pathology. Neer and Hawkins’ tests assess for impingement. O’Brien’s and labral shear are utilized to assess for a SLAP tear.

Particular attention should be paid toward an assessment of laxity and joint translation. Signs of generalized ligamentous laxity are not usually seen in throwers but nevertheless should be evaluated in cases where concern for instability exists. In the office setting, inferior, anterior, and posterior translation are assessed and graded on a scale of 1 to 3. Both shoulders are examined and the involved shoulder is compared versus the contralateral but not graded against the contralateral as is done in the knee. The goals of the examination are to determine if there is increased anterior translation, with or without reproduction of pain.

In the seated position, inferior translation is assessed via the sulcus sign. The scapula is first stabilized with one hand and with the arm in adduction traction is applied to the distal arm with the other hand. Inferior translation is graded as 0 to 3 based on the amount of inferior displacement. Grade 1 is defined as less than 1 cm, 2 is 1 to 2 cm of inferior translation, and 3 as greater than 2 cm. It is important to note that normally the humeral head sits 7 to 8 mm below the acromion. Therefore, an acromiohumeral distance of 1.2 cm implies only 4 to 5 mm of translation but is grade 2. A positive sulcus sign does not itself lead to a diagnosis and it is important to corroborate evidence of instability on exam with symptoms (13, 14, 15). Anterior and posterior translation is assessed in both the supine and seated position with the load and shift test. With the arm supported in the neutral plane of the scapula, with one hand, the examiner applies an axial load to center the humeral head in the glenoid. The humeral head is translated anteriorly and posteriorly on the glenoid. Laxity is graded from 1 to 3 as follows: one, increased translation short of the glenoid rim (0 to 1 cm); two, translation with perching onto the glenoid rim (1 to 2 cm); and three, translation over the glenoid rim (greater than 3 cm) (13, 14, 15).

The internal impingement test is performed supine at 90 degrees of abduction and maximal external rotation, recreating the position of late cocking. Pain at the posterior aspect of the glenohumeral joint is considered a positive test. The relocation test performed at 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation is used to assess for internal impingement. Relief of pain with a posteriorly directed force on the upper arm is positive, i.e. a posterior relocation test (Fig. 20-3). In the thrower, it is important to note that posterior pain that is relieved with relocation suggests internal impingement (6). The posterior force relieves the contact by preventing tissue infolding between the cuff and labrum. In the classic apprehension test for anterior instability, relocation relieves the apprehension.

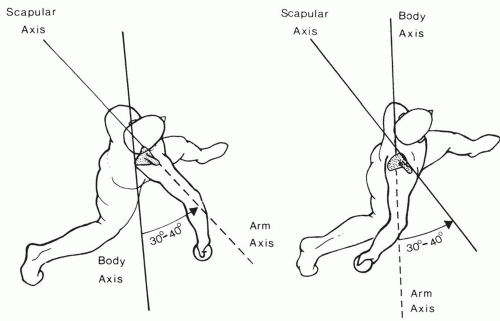

As the kinetic chain and scapulothoracic mechanics play an integral role in the pathology of the throwing shoulder, a full assessment of throwing mechanics should be performed. Poor mechanics include opening up, a dropping elbow, and hyperangulation (Fig. 20-4). These are all factors in pathology of the throwing shoulder. While this is a surgical technique text, it is important to that rehabilitation is the mainstay of treatment for the thrower’s shoulder. The majority of throwers can be successfully managed with a period of rest and supervised physical therapy (16, 17, 18).

It is important to evaluate for scapular dyskinesis, posterior structure tightness, pectoralis tightness, poor joint position sense, and rotator cuff weakness or poor endurance. Scapular dyskinesis is best evaluated by testing the patient from behind. The patient repeatedly elevates both arms at a moderate pace, while the examiner looks for dyskinesis or winging. Winging is maximized by performing resisted shoulder flexion at 30 degrees of elevation or by performing a wall push-up. Posterior tightness is evaluated by decreased horizontal adduction and loss of motion on the internal rotation side of the motion arc. Pectoralis tightness is often present in those with a rounded posture and protracted scapula. At our institution, our physical therapy rehabilitation program for scapular dyskinesis and rotator cuff weakness focuses on resistance band and isotonic exercises. Band exercises for scapular dyskinesis include low and high rows, bear hugs, seated upright rows, push-up plus, and bow and arrows. Proprioception is improved with rhythmic stabilization exercises in multiple positions moving toward functional range of motion. Body blade and other perturbations are used at different positions to improve kinematic awareness and proprioception. Rotator cuff band exercises include external and internal rotation at 0 and 45 degrees, high rows,

and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation D2 patterns, when asymptomatic band exercises are performed at 90 degrees of abduction (Shanley, E., Thigpen, C.: Proaxis Therapy. Greenville, SC, personal communication.).

and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation D2 patterns, when asymptomatic band exercises are performed at 90 degrees of abduction (Shanley, E., Thigpen, C.: Proaxis Therapy. Greenville, SC, personal communication.).

FIGURE 20-3 Modified shoulder relocation test performed at 90, 100, and 110 degrees of shoulder abduction. |

Posterior soft tissue is mobilized with cross-body and sleeper stretches and joint mobilization. Anteriorly pectoralis stretching and soft-tissue subscapularis mobilization are utilized (Shanley, E., Thigpen, C.: Proaxis Therapy. Greenville, SC, personal communication.). The pectoralis is stretched by placing a rolled towel between the shoulder blades with the patient supine and pushing posteriorly on the shoulders or by single arm on wall stretch. If someone has no improvement within 3 months of conservative rehabilitation or is unable to return to play within 6 months, we consider them as failing conservative management.

Knitve and Jobe classified anterior shoulder pain in throwers into four groups (see Table 20-1). Although perhaps helpful, this classification is largely historical. Group I patients were classified as having primary impingement without evidence of increased anterior translation. Impingement testing resulted in pain, whereas anterior translation testing, including under anesthesia, was negative. This was a small subset of patients and generally over 35 years of age. Group II includes patients with primary microanterior instability and resulting secondary impingement or secondary internal impingement. They noted that these patients often have relief of

pain with a relocation test but will not have apprehension in the ABER position. Group III was noted to have generalized ligamentous laxity with secondary impingement. Exam under anesthesia demonstrated laxity in both shoulders. Group IV were patients with pure primary instability (traumatic) without evidence of impingement (6). In this classification, the throwing athlete fits into Group II.

pain with a relocation test but will not have apprehension in the ABER position. Group III was noted to have generalized ligamentous laxity with secondary impingement. Exam under anesthesia demonstrated laxity in both shoulders. Group IV were patients with pure primary instability (traumatic) without evidence of impingement (6). In this classification, the throwing athlete fits into Group II.

FIGURE 20-4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|