Abstract

Introduction

The Hospital Organization Guidelines (HOG) recently recommended that Reference Hospitals create Post-Acute Rehabilitation Units (PARU). The authors describe the quality process of a PARU in a University Hospital (UH); this quality process had previously been used in a private rehabilitation hospital.

Goals

The authors wanted to evaluate the organization of the care provided in their PARU and compare the evaluation results with the results expected at the unit’s creation five years earlier.

Methods

The evaluation indicators were set when the unit was created. These indicators allowed the evaluation of the appropriateness of admissions, the efficiency of the care path and the response to the patients’ rehabilitation and intensive care needs.

Results

The appropriateness of admission was found to be coherent with the typology of patients admitted (i.e., brain and spinal cord injured patients just discharged from intensive care units). The brain-injured care path was streamlined. The evaluation results raised several questions about the resources provided and about the different needs of post-acute care and rehabilitation.

Discussion and conclusion

Patient needs must be identified precisely if the weak links of the care path are to be reinforced. The indicators used must be capable of assessing both the quantity and the quality of care. If these indicators lack relevance, or if the health care organization responds incompletely to patient needs, it puts the efficiency of the whole system at stake.

Résumé

Introduction

La création de services de rééducation en post-réanimation (SRPR) dans des hôpitaux dotés de tous les plateaux techniques spécialisés, a été recommandée par le SROS. Un établissement de soins de suite et de réadaptation, qui avait été à l’origine du concept de SRPR, a accepté d’implanter en 2003 un tel service au sein d’un CHU. Les auteurs rapportent à ce sujet une approche d’amélioration continue de la qualité.

Objectifs

Les auteurs font le point, à cinq ans de fonctionnement, sur les résultats obtenus par rapport aux résultats attendus lors de l’établissement initial du cahier des charges.

Méthodes

Les indicateurs de l’évaluation ont été posés dès la création du SRPR : pertinence des admissions, fonctionnement de la filière de soins et réponse aux besoins en soins de MPR et de réanimation.

Résultats

La pertinence des admissions est cohérente pour la typologie de patients admise. Les résultats de l’évaluation interrogent quant aux moyens proposés. La filière des cérébrolésés graves a été fluidifiée. Les réponses aux besoins diffèrent entre la MPR et la post-réanimation.

Discussion et conclusion

Le renforcement d’un maillon faible dans une filière de soins nécessite de préciser scrupuleusement les besoins en soins de la population prise en charge. Les indicateurs doivent être quantitatifs et qualitatifs. S’ils manquent de pertinence, ou si l’organisation mise en place n’y répond pas exactement, c’est l’efficience de tout le système qui est en jeu.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

The instability of severe neurological lesions after cerebral and medullary injuries is a major challenge for care path organization, from the initial treatment phase in intensive care and neurosurgery units to the stabilized phase in the rehabilitation unit . Many studies have focused on the public health concerns pertaining to the quantitative and/or qualitative deficiencies in the care facilities after the acute care phase, but the Anglo-saxon expression, post-acute care , does not exactly represent the concept presented in this article, post-acute rehabilitation . The exception of the Anglo-saxon early care for patients with high-level cervical medullary injuries confirms the rule .

Created by the publication of the 1996 decrees, the French Regional Hospitalization Agencies (ARH) had as their primary objective to adjust the care offer to the care demand. They did this by trying to locate the “weak links” in the organization of the health care paths. For neurology, the work groups of several Hospital Organization Guidelines (HOG) committees confirmed the fundamental problem found in the literature.

The patients with severe cerebral lesions and high-level cervical medullary injuries need a specific treatment protocol when they come out of intensive care, before they are admitted to a Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PMR) unit . Physical therapy treatments and awareness facilitation techniques don’t appear to be optimal in intensive care and neuro-surgical intensive care , while the transfer to traditional rehabilitation unit provokes patient safety fears due to their still unstable vital functions. As early as the beginning of the 1970s, several teams in France and Germany (notably the Schmieder Neurological Clinic) tried to respond to the need for early treatment when the patient was released from intensive care, in the form of awareness recovery units. One of the problems that resulted from the lack of early treatment was the patient’s non-programmed rehospitalization, which is an indicator of non-quality that has been used in medicine, particularly surgery, for 40 years.

In 1991, we established a post-acute rehabilitation unit (PARU) and presented the first results for these units at the 8th National SOFMER Conference in 1993. The organization of such units, with continuous monitoring supervised by an intensive care doctor and rehabilitation methods appropriate for severe cerebral lesions, was recognized by the ARH after being reviewed by the technical committee responsible for preparing the hospital organization guidelines. Thirteen years later, this model would be reused in the hospital administration memorandum of 18 June 2004 pertaining to the medical, medical-social and social care path of patients with cranial trauma and medullary injuries .

This first post-acute rehabilitation unit (PARU) had the advantage of being located in a large rehabilitation center, which permitted the easy mobilization of the rehabilitation resources within the PARU. However, although the medical organization of continuous care sharply reduced patient morbidity and non-programmed rehospitalization, we had to follow the HOG recommendations (which we had helped to write!), moving nearer to the specialized short-term care services, particularly intensive care and neurosurgery. It was in these circumstances that a private follow-up care and rehabilitation facility, with 10 years of experience in this type of treatment, accepted to set up a PARU inside a University Hospital in which the PARU had already established a care path specifically for patients with severe cerebral lesions and some patients with high-level cervical medullary injuries.

This paper presents our experiences with a quality control process in a health care facility whose care specifications had been scrupulously written based on public health documents that had been validated by a HOG committee. “Best practice” clinical care protocols and their implementation by PARU professionals are outside of the scope of this paper. We send interested readers to our synthesis on this subject in the Encyclopédie Médico-chirurgicale . Based on the research of W. E. DEMING , the objective of this study was to control the organization established to respond correctly to what was envisioned, using performance indicators , methods and results in order to highlight the areas that need improvement.

Since the first version of the accreditation process in 1999, the French National Authority for Health (HAS), as well as the French National Agency for Health Care Accreditation and Evaluation (ANAES) that preceded it, has recommended that health care facilities evaluate patient satisfaction in order to complete the patient pathway evaluation. Such methods for appreciating the perceived quality measure the satisfaction compared to expectations, while the patient pathway evaluations measure the resources used to respond to patient needs.

In the same vein as Ernest Codman’s morbidity and mortality conferences , we developed criteria allowing quality, safety and performance levels to be measured, not using clinical indicators as such, but evaluating the appropriateness of the care path and the resources used to respond to the public health imperatives in a PARU.

1.2

Objectives

Before setting up the new Post-Acute Rehabilitation Unit (PARU), we wrote precise specifications in order to make this unit operate according to best practices. These specifications were based on clinical recommendations, public health recommendations and the analysis of our experience with operations of the first PARU, established 10 years earlier. The specifications thus proposed patient care procedures, from the admissions request to the search for a patient management plan on discharge from the PARU, including an offer of a partnership to follow-up care facilities that accepted to admit the patients.

The PARU was managed by a Health Care Cooperative. This management was based on a charter, a quality assurance document that imposed certain criteria on the partners in the care path, thus constituting a guarantee for patient care. The goal of this paper is to show how this charter was followed using indicators that allowed us to correct the gaps observed compared to the objectives that had been set. In addition, this assessment would allow both establishments to prepare for the challenges of the new certification process, V2010 . As a complement to the improvements proposed for the organization of care, the method for monitoring the indicators must be completed in future research by an evaluation of clinical practices and expected results.

1.3

Methodology

Recommended by the French National Authority for Health, our methodology involves monitoring indicators to evaluate professional practices . These evaluation indicators were established at the creation of the first PARU. It is necessary to emphasize here that these indicators are not generalizable because, from the start, the indicators were chosen to conform to the objectives established in the PARU charter.

The nine indicators monitored are listed below.

1.3.1

Indicator R 1

Indicator R 1, which is specific, represents the traceability of the care path of patients with severe cerebral lesions. These patients must be monitored as they go from intensive care to the PARU to the follow-up care facility. The appropriateness of the patient management plan at admission to, and discharge from, the PARU must be measured.

1.3.2

Indicator R 2

Indicator R 2, non-specific, monitors the bed occupancy rate (12 beds) of the PARU; the average length of stay (ALOS), which should not exceed 3 months to avoid making the condition chronic; and the annual number of admissions, initially set at 50, which must be attained or exceeded.

1.3.3

Indicator R 3

Indicator R 3 permits the evaluation of the effective care of patients directly after their discharge from a regular intensive care unit (ICU) or a post-operative intensive care unit (Post-Op ICU). It is necessary to insure that the PARU has done a good job in providing post-acute care. We have already studied this indicator, which is specific to the treated population, during an appropriateness review done in the context of the V2007 certification .

1.3.4

Indicator R 4

Indicator R 4, non-specific, monitors the waiting time between the ICU’s request for patient admission, the PARU doctor’s visit to the candidate patient and the actual admission to the PARU . This indicator is completed by the ALOS of intensive care patients and by the satisfaction rate from a survey of the upstream professionals and the patients and/or their families.

1.3.5

Indicator R 5

Indicator R 5, non-specific, insures the continuity and safety of the care provided. This indicator was constructed and monitored with the help of the care managers, which permitted the involvement of management in the continuous improvement process. As a dashboard, the number of nurses was reported for mornings, evenings, nights, holidays and weekdays, and compared to the number considered appropriate for critical care and for dependency assistance in a 12-bed PARU.

The number necessary for rehabilitation was established based on the needs with respect to physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, psychomotor therapy and social services. These needs appear to be quantitatively and qualitatively different from the needs that can be found in other types of teams, both in France and other same-level countries . The needs themselves had been quantified based on the analysis of the first PARU operations (i.e., weekly number and length of interventions). The actual numbers observed in the PARU’s operations were compared to the numbers considered to be necessary.

The medical coverage was evaluated for each business half-day. The number of times the on-duty intensive care personnel were called into the PARU, as well as the medical interventions that they performed, was noted for nights, weekends and holidays. This part of the indicator is specific to the post-acute rehabilitation program.

A survey of patient satisfaction (and their families’ satisfaction), measuring the perceived quality in the 3 months that follow the discharge from the PARU, completed this indicator. Although other studies have focused on intensive care, it is difficult to generalize their results to the PARU .

1.3.6

Indicator R 6

Indicator R 6, non-specific, is linked to best care practices through training programs and protocol writing. At the end of this study, our results compared to clinical best practices should complete this evaluation of the PARU organization.

1.3.7

Indicator R 7

Indicator R 7 allows the typology of patients admitted to the PARU (i.e., brain and high-level spinal cord injuries) to be monitored using, as a dashboard, the figures from the Medicalized Information System Program (MISP) provided by the Medical Information Department. In this sense, the method is not specific to PARU monitoring ( Table 1 ).

| Primary clinical categories | 2003/2004 (%) | 2007 (%) | 2008 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11- Cardiovascular & respiratory | 4.9 | 18 | 9.2 |

| 12- Neuromuscular | 88.3 | 79 | 87.6 |

| Levels of care | |||

| Very severe clinical treatments | 6.9 | 6.60 | 14.5 |

| Severe clinical treatments | 67.8 | 79.40 | 72.1 |

| “Complex rehabilitation” treatments | 0.2 | 0.17 | 0.00 |

| “Rehabilitation” treatments | 7.4 | 5.28 | 1.6 |

Among the obligations contained in the charter are the precisions about the typology of patient that should be admitted to a PARU: patients who have a severe cerebral or spinal cord injury, regardless of whether or not it was caused by trauma. Due to their deficiencies, the patients admitted to a PARU might need respiratory aid to help stabilize their vital functions .

Among the primary clinical categories, we chose to study the importance of cardio-respiratory deficiencies instead of neurological deficiencies, since sometimes the patients have primary cardio-respiratory deficiencies, complicated by secondary neurological deficiencies, such as intensive care neuropathies. This indicator alerts upstream intensive care specialists of a possible drift in the entrance criteria towards non-neurological pathologies. In fact, the PARU was created to cater to patients with severe neurological problems complicated by difficulties stabilizing their vital functions, especially respiratory functions.

The importance of technical acts and the specialized medical interventions are evaluated through the rate of “very severe” and “severe” clinical treatments, focusing on the “Post-Acute” part of the Post-Acute Rehabilitation Unit. “Rehabilitation” treatments and “complex rehabilitation” treatments allow the care density to be quantified for each category of rehab specialists, focusing on the “Rehabilitation Unit” part of the Post-Acute Rehabilitation Unit. Again, the literature consulted didn’t mention an organization like the PARU, which makes any comparison risky.

1.3.8

Indicator R 8

Indicator R 8, non-specific, measures the failures of the PARU environment and equipment. Used a lot to manage care quality and safety, this indicator is weakened by the lack of exhaustivity of the undesirable event declarations. On the other hand, it was the reading of the results for the declaration of undesirable events, and their analysis, that compelled the quality assurance service and the health care facility’s management to propose a new method for declaring undesirable events that was easier, more attractive and more rewarding.

1.3.9

Indicator R 9

Indicator R 9 allows the budget equilibrium to be monitored in terms of the assigned resources. Not specific to PARU operations, this indicator is used by the administrative and financial services of both facilities for expenditures for personnel, logistics services and certain medical services (e.g., on-duty and on-call intensive care personnel paid by the University Hospital).

Table 2 only reports the important expenditures and receipts that allow the macro operations to be monitored on the PARU management dashboard. In cases of inflation or deflation of a budget line, the analytical accounting procedure set up by the facility allows the failures to be analyzed more precisely. For example, this is what happened when the nursing and rehabilitation expenditures exceeded the needs stated in the original charter.

| R9: Budgetary equilbrium in terms of allocated resources | |

|---|---|

| Annual Budget (€) | Gap expenditures/budget (€) |

| 2OO3/2004: 1 506 465 | -65 000 |

| 2007: 1 834 988 | -6 274 |

| Subtotal personnel (€) | Gap subtotal personnel (€) |

| 2003/2004: 1 506 465 | +21 400 € |

| 2007: 1 590 623 | +12 325 € |

| Subtotal logistics & medical expenditures (€) | Gap subtotal logistics & medical expenditures (€) |

| 2003/2004: no declaration of the provisions for expenditures & receipts | -86 400 |

| 2007: 210 000 | -21 100 |

The patient satisfaction survey was developed and conducted by the quality assurance service at the private follow-up and rehabilitation facility that came up with the idea of the PARU, with the help of user representatives on Care Quality and User Relationships Commission (CRUQ) of this facility.

1.4

Results

From October 2003 to December 2008, 263 patients were admitted to the PARU created inside the University Hospital. Since the objective of this study was to monitor the indicators globally over a 5-year period, we compared the figures for 2003/2004, from the beginning of operations, to the figures for 2007/2008, after 5 years of operations. The results of this comparison are listed below.

1.4.1

Indicator R 1

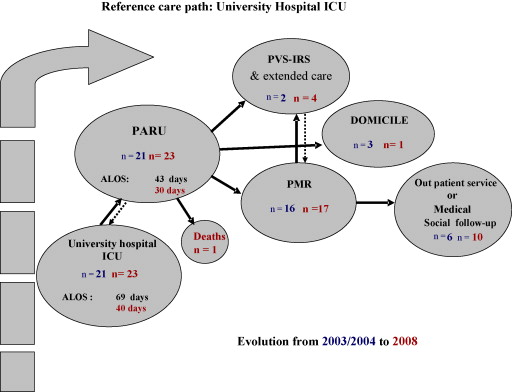

As shown in Fig. 1 , it was the primary care path from the University Hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU) that served as a tracer. This unit, situated close to the PARU, represents 70% of admissions in the French department in which the UH is located. Admissions on this reference (i.e., primary) path are stable. The average length of stay (ALOS) in ICU, which is the source of this path, went from 69 days to 40 days; the ALOS in the PARU was reduced by 30% for the patients on this path but remained high for the other care paths in the department. Our traceability analysis after the PARU opened shows a significant growth in the patients cared for in outpatient clinics and medical-social structures.

1.4.2

Indicator R 2

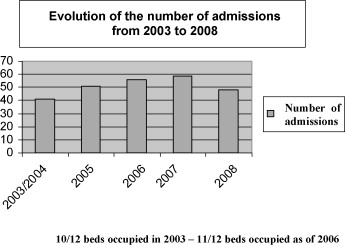

This indicator uses the number of patients admitted, the bed occupancy rate and the ALOS to measure the PARU’s activity ( Fig. 2 ). The annual number of admissions progressed regularly from opening of the PARU until 2007, with a 20.4% increase. However, in 2008, there were only 48 patients admitted. This decrease in admissions can be explained by the presence of ventilated patients, for whom organizing a discharge was difficult, increasing the length of their stay and preventing the admission of new patients. The fluidity of the care path was also reduced by a great increase in the length of stay in the units downstream from the PARU, thus disturbing the discharge from the PARU for the patients in a persistent vegetative state and/or inconsistent relational state (PVS-IRS). The bed occupancy rate went from 83.3% in 2003 to 91.6% in 2008. Indicator R1 highlighted the evolution of the ALOS in the reference care path.

1.4.3

Indicator R 3

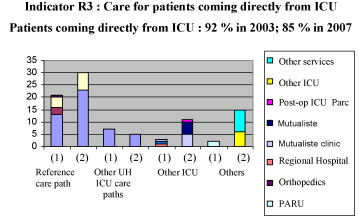

This indicator measures the appropriateness of the patient management plan from ICU to PARU ( Fig. 3 ). The appropriateness score of 92% in 2003/2004 was high, compared to 85% in 2008. The difference is essentially due to PARU re-admissions of patients in follow-up care facilities, who wanted to benefit from the PARU’s technical resources for short-term evaluatory visits. This typology of readmitted patient is nonetheless appropriate since the PARU must provide this type of care because it figured initially in the PARU charter.

1.4.4

Indicator R 4

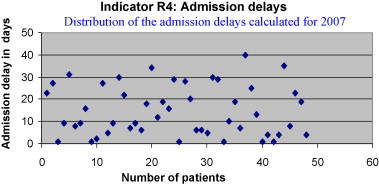

This indicator measures waiting time. It is necessary to distinguish between a) the time between the admissions request and the pre-admission visit of the PARU doctor in ICU and b) the time between the actual admission to the PARU and the initial request. The patient was admitted with same delay for both periods considered: an average of 18 days in 2003/2004 and an average of 17.44 days in 2007. The time between the reception of the admission request and the pre-admission visit passed from 8 ± 14 days in 2003/2004 to 13.5 ± 10 days in 2007, with the standard deviation being insignificant. In all cases, the requests were executed very early by the ICU so that an admissions file would be opened; however, the patients were not ready to be discharged.

The distribution of the delay values ( Fig. 4 ) doesn’t allow a significant comparison to be made. This distribution of the delays is due to the instability of patients’ vital functions and the capacity of the PARU. Since this indicator provides information that is not relevant, it will have to reconstructed, using the measurements of the time separating the date on which the patient is able to leave ICU and the date when the patient is actually admitted to the PARU.

1.4.5

Indicator R 5

This indicator measures the continuity of care and care safety using the level of coverage of nurses and rehabilitation specialists ( Table 3 ). Medical coverage is maintained at a level appropriate for senior medical doctors, but the distribution of presence was less homogeneous during the second period. On the other hand, the presence of residents was greatly improved, despite their absences for training and compensatory rest periods and being on-call. The resident contracted to the PARU by ICU was less solicited and less called to move around the PARU during the second period, but in any event responded to critical situation that occurred.

| Year | 2003-2004 | 2007-2008 |

|---|---|---|

| Medical coverage in the PARU | 90% | 91% |

| Presence of a resident in the PARU | 57% | 74% |

| Calls for the on-duty resident | 123 | 81, of which 13 were multiple |

| ICU resident trips to the PARU | 49 | 27 |

| Weekday coverage | 94% | 95.30% |

| Weekend coverage | 74% | 95.10% |

| Rehab coverage | Numbers unstable | 86% |

| Temporary workers (in hours) | 4605 h | 1477 h for physical therapy |

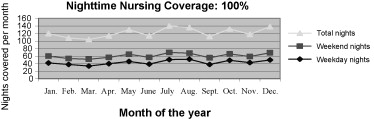

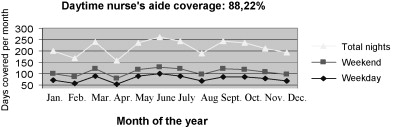

A more precise analysis of the presence of nurses shows the coverage of the shifts was quasi stable nights and weekends, periods during which the numbers cannot descend below a safety threshold ( Fig. 5 ). For the nurse’s aides, the daytime coverage never exceeded 88.22% ( Fig. 6 ). This situation can be explained by the priority given to nurse replacement to insure patient safety. The coverage of rehabilitation specialists was only 86%, although there were 1477 hours available for temporary physical therapists.

The other categories of rehabilitation specialists (occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, psychomotor therapists) intervened on request from a staff pool at the previous site of the PARU, before this unit moved to the UH. Since the PARU was established at the UH, these professions can no longer move about in the same manner; the two sites are too far from one another and the UH partner does not compensate for this distance. This issue is even more preoccupying since, in the rehabilitation team, each person plays a specific role and can’t be replaced by a professional from another discipline, especially in the case of the psychomotor therapists .

1.4.6

Indicator R 6

This indicator allows the level of quality assurance to be measured, through the production of documents, such as reference procedures and protocols for best care practices ( Table 4 ). Training programs constitute a part of this quality indicator, whether they be about best care practices in general or best care practices for PARU, or even programs for all personnel about quality and safety (e.g., patient rights, health care proxies, fires). These training programs were not listed in 2003 because it was difficult to identify them since the PARU was not yet open at the UH. Nonetheless, the quantitative and qualitative importance of the preparation of the teams of health care providers (i.e., doctors, nurses, nurse’s aides, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, psychomotor therapists) before the PARU moved to the UH must be emphasized.

| Quality Assurance documents | 2003 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|

| Protocols | 2 | 45 |

| Procedures | 6 | 15 |

| Technical sheets | 4 | 25 |

| University Hospital logistics brochure | Approval process underway | Total use of the brochure |

1.4.7

Indicator R 7

This indicator uses the annually-published MISP data in the activity assessments ( Table 1 ).

The two primary clinical categories (PCC) — “neuromuscular” and “cardio-vascular/respiratory” — account for 96% of the PCC in 2003. The cardio-vascular/respiratory problems have increased more than 200% since the PARU opened. This increase is due to 2 factors: 1) the greater instability of the vital functions in patients with cerebral lesions and spinal cord injuries admitted to the PARU, and 2) the typology of patients in one of the intensive care units, which was gradually extended to other pathologies in which the clinical care is dominated by the monitoring of cardio-vascular and respiratory functions. This evolution of the cardio-vascular and respiratory PCC was accompanied by an increase in severe clinical treatments of +17%, while the very severe clinical treatments remained stable. Nevertheless, the “neuromuscular” category, which includes the neurological patients whose treatment is focused on the deficiencies caused by the cerebral or spinal cord injury, remained predominant in 2007/2008, with 79% of the PCC.

The rate of rehabilitation treatments, complex or not, shows a significant decrease of 66%. This figure should be compared to the figure for rehabilitation coverage (86%) and to the satisfaction rate of patients and their families for certain rehabilitation services.

1.4.8

Indicator R 8

This indicator, based on declarations of undesirable events, measures the number of situations in which the care quality and safety was inappropriate. It allowed us to monitor the quality assurance and risk control processes (e.g., management of the distributing pharmacy and monitoring systems) and to continue corrective action on the other persistent operational problems (e.g., the endoscope decontamination room and inter-site computer connections). A follow-up evaluation is nonetheless vital, which means it is necessary to control the quality of different procedures within the year that follows.

1.4.9

Indicator R 9

This indicator measures the equilibrium between the PARU’s allocated resources and its expenditures. This budgetary monitoring shows an increase in the allocated resources of 328 523 €, or + 21.81% in 5 years. In 2003/2004, the budgetary allocation for staff was not totally spent; the amount not spent was 21 400 €. In 2008, with a higher staff budgetary allocation (+90 000 €), the amount that was not spent was only 12 325 €. As a result, there was a supplementary expenditure of 99 000 € in 2008 compared to 2003/2004. This increase corresponds to improved nursing coverage ( Fig. 4 ).

1.5

Patient satisfaction survey

The satisfaction survey, conducted by the quality assurance service in complement to monitoring the indicators described above, concerned the “clients” of the PARU:

- •

the professionals who are upstream and downstream from the PARU;

- •

the professionals who work in the PARU itself;

- •

the patients, and their families, who “use” the PARU.

1.5.1

Satisfaction of the upstream/downstream professionals

1.5.1.1

Upstream

Four intensive care doctors, one neurosurgeon and five care managers, whose names were drawn randomly, were surveyed by the quality assistant of the follow-up care and rehabilitation facility. In addition to the global level of satisfaction with the care path operations, this part of the survey pointed out 2 directions for improvement: first, work together on the admissions delays and, second, work together to come up with a specific rehabilitation program for patients waiting to be admitted.

1.5.1.2

Downstream

Two PMR doctors and a doctor in a medicalized follow-up care facility were surveyed. In addition to the global level of satisfaction with the care path operations, two directions for improvement were highlighted: first, conduct joint training programs for the teams involved and, second, think about a functional rehabilitation program that goes from intensive care to rehabilitation.

These professionals were worried about the care path quality when the PARU was made a part of the ICU/emergency department. In fact, until the PARU moved, the originality of its operational mode was its proximity to the University Hospital’s 2 technical platforms — Physical Medicine and ICU/neurosurgery — without any pressure being exerted to move in either of these directions (rehabilitation or intensive care). It is thus legitimate to wonder about the influence of being hosted in a department entirely devoted to emergency medicine and intensive care.

1.5.2

Satisfaction of the PARU professionals

Two directions for improvement were highlighted by the responses to the survey: the need for training and specific procedures for “well-treatment” and for pain ; and inter-disciplinary information sharing, in spite of the organization already set up to respond to this need. Five of the nine surveyed professionals were touched, near or far, by “burn out”.

1.5.3

Satisfaction of former patients (as much as possible) and their families

The survey involved 100 patients that had been discharged from the PARU less than two years ago and more than one month ago ( Table 5 ). The survey was conducted by mail; for 34 patients and/or their families whose responses could not be obtained by mail, the survey was conducted by telephone. Only the responses with a level of satisfaction under 75% were retained. Two groups of questions were raised: one about the communication with the nursing team, especially with the nurse’s aides, when the care was provided; and one about the rehabilitation services provided, outside the physical therapy sessions.

| Patient satisfaction survey topics | % satisfied |

|---|---|

| Waiting Time | 61.76 |

| Patient welcome and installation | 88.24 |

| Patient rights and information | |

| Access to patient files Patient and/or family associated to care project Communication with the nursing team | 79.41 85.29 59.00 |

| Satisfaction with treatment | |

| Nurses Doctors Nurse’s aides | 85.41 85.29 71.88 |

| Rehabilitation services | |

| Physical therapy Occupational therapy Speech/Language therapy Psychomotor therapy Social services | 81.82 61.29 45.45 38.71 75.76 |

1.6

Discussion and conclusion

There were three primary objectives when writing the specifications for the PARU transferred from the follow-up care and rehabilitation facility to the rooms set aside by UH for its use:

- •

determine what exactly were the patient needs for the PARU treatment program,

- •

determine the resources and the care organization required to respond to these needs,

- •

involve the internal and external partners directly in defining and implementing the treatment program.

In addition to these objectives, the program’s management and quality assurance teams had to have monitoring tools: the indicators described in section III and the dashboards. For clinical practices, the validated tools for the clinical evaluation of the physical and cognitive consequences of coma were routinely used in the PARU according to the recommendations . In fact, an evaluation is part of the facility’s annual evaluation program for professional practices. However, this was not one of the objectives of this study.

Using these indicators allowed us to monitor the PARU, from its creation to its move, five years later. Each year, in the annual activity report, these indicators were used to evaluate the conformity to the objectives of the initial project. The medical and administrative managers of the Health Care Cooperative could use a dashboard, thus allowing the faulty element to be corrected.

The advantages of an evaluation such as the one reported here.

The work undertaken during a professional practices evaluation (PPE) must be prolonged to limit the inappropriate admissions to the PARU, thus increasing the potential of this unit to receive patients.

Two indicators were dealt with: the mortality rate and the non-programmed re-admission to the ICU. The results already published on these indicators are not relevant because these results refer to structures different from the PARU. Nonetheless, the comparison can be made with the results obtained from an analysis of the results for the same unit before 2003. In the light of this comparison, an improvement program doesn’t seem to be really needed. Still, compared to the medical supervision best practices in the context of post-acute continuous care, the indicators chosen (i.e., stabilization of vital parameters and lack of evolving infectious and neurosurgical complications) must be subject to continual evaluation in addition to specific training programs and certain protocols requested by the nursing staff in the satisfaction survey.

In terms of the “Rehabilitation Unit” part of the PARU, the study of admissions appropriateness, crossed with the evaluation of the number of PARU staff and the responses to the satisfaction survey, reveals the relative unavailability of professionals compared to the required criteria. Table 5 provides a chart of the satisfaction of patients and the families for physical therapy sessions, which are given an average of twice per day. Other professionals, especially psychomotor therapists, cannot be present on-site at the frequency called for in the specifications. This is one of the consequences of the distance of the PARU from its human resources pool, which is at another site.

The functional results are measured by the Functional Independence Measure (FIM), an indicator systematically calculated on the admission and discharge of the patient. Recent publications, as well as a study from one of the authors of this paper, on the subject of using the FIM for patients with severe cerebral lesion refer to the future functional evolution of patients with severe cranial trauma. In the post-acute phase, this indicator doesn’t appear to be relevant to measure the rehabilitation results.

Other indicators (e.g., the Glasgow Coma Scale, the Jouvet score, Rancho Los Amigos Cognitive Recovery Scale, Galveston Orientation and Amnesia Test (GOAT) scale, Wessex Head Injury Matrix (WHIM) scale) are routinely used in the PARU to measure neurological and behavioral improvements . According to Majerus and Van der Linden, it would be possible to use these measurement tools to evaluate the effectiveness of facilitation techniques in rehabilitation .

The expected quality of life has already been measured downstream of the PARU and, in other works , it has been measured upstream, after the patient has been discharged from ICU. Lacking a measure of the validity of this indicator in a PARU, we used the survey of the satisfaction of patients and their families to measure, not the expected, but the perceived care quality. The improvement program was broached with the user representatives, who are part of the Care Quality and User Relationships Commission (CRUQ). One of the missions of this commission is to give its opinion on directions for improvement and to insure these directions are followed up.

For the PARU professionals to appropriate the quality improvement program and make it their own, it is necessary to formalize a consultative body, like the service committees and the morbidity/mortality reviews. This last monitoring method (i.e., morbidity/mortality reviews) is currently being set up, with the objective of detecting the weak links in the care programs. The last condition for setting up the permanent quality improvement program for PARU patient care is the priority of the strategic orientations. The PARU’s move to a favorable environment for such a dynamic is also an opportunity to set up a quality assurance program.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La précarité des lésions neurologiques graves à la suite de lésions cérébrales et médullaires est un enjeu majeur dans la filière de soins, depuis la prise en charge initiale en réanimation et en neurochirurgie jusqu’à la phase stabilisée en rééducation et réadaptation .

De nombreux travaux font état des préoccupations de santé publique quant à la carence quantitative ou qualitative de structures de prise en charge après la phase de réanimation, mais le vocable anglo-saxon de post-acute care ne recouvre pas strictement le concept dont une présentation est faite dans ce travail, la rééducation post-réanimation. L’exception des programmes anglo-saxons de prise en charge précoce des blessés médullaires de niveau cervical haut, confirme la règle .

Dès leur création, après la publication des ordonnances de 1996, les Agences régionales de l’hospitalisation (ARH) ont eu pour objectif prioritaire d’ajuster l’offre de soins à la demande en s’efforçant de repérer les « maillons faibles » dans les filières de soins. Pour la filière de neurologie, les groupes de travail de plusieurs SROS ont confirmé la problématique retrouvée dans la littérature. Les cérébrolésés graves et les blessés médullaires de niveau cervical haut, ont en effet besoin d’une prise en charge spécifique à la sortie de réanimation, avant d’être pris en charge dans un service de médecine physique et de réadaptation . La prise en charge de kinésithérapie et les techniques de facilitation de l’éveil n’apparaissent pas optimum en réanimation et en soins intensifs neurochirurgicaux , tandis que le transfert vers une unité de médecine de rééducation traditionnelle fait craindre pour la sécurité vis-à-vis des fonctions vitales encore instables. Dès le début des années 1970, plusieurs équipes en France et en Allemagne (notamment la clinique neurologique Schmieder) s’étaient déjà efforcées d’apporter une réponse de prise en charge précoce après la réanimation ; on parlait alors d’unités d’éveil. L’un des problèmes qui résulta de ces prises en charge fut la réhospitalisation non programmé, indicateur de non-qualité déjà utilisée en médecine et en chirurgie depuis 40 ans.

Les auteurs mirent en œuvre le concept de services de rééducation en post-réanimation (SRPR) dès 1991 et présentèrent leurs premiers résultats au 8 e Congrès national de la Sofmer en 1993. L’organisation d’une telle structure, comportant des moyens de surveillance continue sous l’autorité d’un médecin réanimateur et des moyens de rééducations adaptés à la cérébro-lésion grave, fut labellisée par l’ARH après avoir été soumise au comité technique de préparation du SROS. Cette modélisation sera reprise, 13 ans plus tard, dans la circulaire de la direction des hôpitaux du 18 juin 2004 relative à la filière de prise en charge sanitaire, médicosociale et sociale des traumatisés crâniens et des blessés médullaires .

Ce premier SRPR avait l’avantage d’être situé au sein d’un centre important de rééducation, ce qui permettait de mobiliser facilement les ressources de rééducation au sein du SRPR. Mais, bien que l’organisation médicale vis-à-vis des soins continue ait nettement diminué la morbidité et les réhospitalisations non programmées, les auteurs furent amenés à suivre les recommandations du SROS (auxquelles ils avaient contribué !), consistant à se rapprocher des services spécialisés du court séjour, notamment de la réanimation et de la neurochirurgie. C’est dans ces circonstances qu’un établissement de soins de suite et de réadaptation privé, fort d’une expérience de dix ans dans ce type de prise en charge, a accepté d’implanter en 2003 un SRPR au sein du CHU avec lequel le SRPR entretenait déjà une filière de soins spécifique aux cérébrolésés graves et à certains blessés médullaires de niveau cervical haut.

L’objectif du présent travail est d’apporter l’expérience d’un contrôle qualité d’une organisation de soins dont le cahier des charges a été minutieusement rédigé à partir de documents de santé publique validés en SROS. Il ne sera pas question ici de parler des protocoles de prise en charge clinique répondant aux bonnes pratiques, ni de leur mise en œuvre par les professionnels du SRPR. Les auteurs renvoient le lecteur à une synthèse qu’ils ont faite à ce sujet dans l’encyclopédie médicochirurgicale .

L’objectif de cette étude, en reprenant les travaux de Deming , a été de contrôler que l’organisation mise en place répond bien à ce qui était prévu, en utilisant des indicateurs de performance, de moyens, et de résultats, afin de mettre en évidence les points à améliorer.

L’Anaes, puis la HAS qui lui a succédé, ont, depuis la première version de la démarche d’accréditation en 1999, recommandé une évaluation de la satisfaction des patients pour compléter l’évaluation du parcours du patient. De telles méthodes d’appréciation de la qualité perçue mesurent la satisfaction par rapport aux attentes, alors que l’évaluation du parcours du patient mesure les moyens mis en œuvre pour répondre à ses besoins.

Dans le même esprit que les conférences de mortalité/morbidité mises au point par Codman , les auteurs ont mis au point des critères permettant de mesurer la performance, le niveau de qualité et de sécurité, non pas dans le domaine des indicateurs cliniques, mais sur la pertinence de la filière de soins et des moyens mis en œuvre pour répondre aux impératifs de santé publique d’un SRPR.

2.2

Objectifs

La mise en place d’un nouveau SRPR a été précédée par la rédaction d’un cahier des charges précis pour le faire fonctionner conformément aux bonnes pratiques. Ce cahier des charges a été élaboré à partir de recommandations cliniques -– et de santé publique et à partir de l’analyse du fonctionnement de dix ans du premier SRPR mis au point par les auteurs dix ans plus tôt].

Le cahier des charges proposait ainsi des procédures de prise en charge, depuis la demande d’admission jusqu’à la recherche d’une orientation à la sortie du SRPR, incluant une offre de partenariat aux services de soins de suite acceptant d’admettre les patients.

La gestion du SRPR par un groupement de coopération sanitaire (GCS) devait s’appuyer sur une charte, document d’assurance qualité s’imposant aux partenaires dans la filière de soins et constituant une garantie pour la prise en charge des patients.

L’objectif de ce travail est de montrer comment le suivi de cette charte a été réalisé par des indicateurs permettant de corriger les écarts constatés par rapport aux objectifs fixés et de préparer le SRPR à se re-localiser en 2009 au sein du département de Réanimation du CHU qui a lui-même déménagé sur un autre site. Ceci permettra en outre aux deux établissements de se préparer aux enjeux de la nouvelle certification V2010 .

En complément des axes d’amélioration proposés pour l’organisation de la prise en charge, la méthode de suivi des indicateurs devra être complétée dans un travail ultérieur par l’évaluation des pratiques cliques et des résultats attendus.

2.3

Méthode

La méthode est celle du suivi d’indicateurs, recommandée par la Haute Autorité de santé dans l’évaluation des pratiques professionnelles .

Les indicateurs de l’évaluation ont été posés dès sa conception du SRPR, Il faut souligner ici que tous ces indicateurs ne sont pas généralisables, car le choix d’indicateurs a été d’emblée adapté aux objectifs fixés dans la charte constitutive du SRPR.

2.3.1

L’indicateur R 1

L’indicateur R 1 est spécifique, il représente la traçabilité de la filière des patients cérébrolésés graves. On doit pouvoir suivre les patients qui vont de la réanimation vers les soins de suite en passant par le SRPR. On doit pouvoir mesurer la pertinence d’orientation des patients aussi bien pour l’entrée que pour la sortie du SRPR.

2.3.2

L’indicateur R 2

L’indicateur R 2 , non spécifique, suit le fonctionnement du SRPR en termes d’occupation des 12 lits, de la durée moyenne de séjour qui ne doit pas dépasser trois mois pour éviter la chronicisation et du nombre annuel des admissions initialement fixé à 50 et qui doit être atteint, sinon dépassé.

2.3.3

L’indicateur R 3

L’indicateur R 3 permet d’évaluer la prise en charge effective de patients directement à la sortie de réanimation ou d’un service de soins intensifs postopératoire (SIPO) : on doit pouvoir s’assurer que le SRPR a bien rempli sa vocation de post-réanimation. Il s’agit d’un indicateur de pertinence spécifique à la population traitée, déjà étudié par les auteurs lors d’une revue de pertinence effectuée dans le cadre de la certification V2007 .

2.3.4

L’indicateur R 4

L’indicateur R 4, non spécifique, suit les délais d’attente entre la demande du service de réanimation, la visite d’un médecin du SRPR auprès du patient candidat à l’entrée au SRPR et la date d’entrée réelle en SRPR . Cet indicateur est complété par la durée moyenne de séjour des patients en réanimation et par le taux de satisfaction émanant de l’enquête auprès des professionnels d’amont et des patients ou de leur entourage.

2.3.5

L’indicateur R 5

L’Indicateur R 5, non spécifique , de la couverture en soins, permet de s’assurer de la continuité et de la sécurité des soins. Il a été construit et suivi avec l’encadrement, ce qui a permis d’impliquer les acteurs du management dans une démarche d’amélioration continue. Les effectifs infirmiers sont comptabilisés en matin, soir, nuit, semaine et jours fériés, et rapportés aux effectifs considérés comme adaptés aux besoins vitaux et en aide à la dépendance dans une unité SRPR de 12 lits.

Les effectifs nécessaires en rééducation ont été établis à partir des besoins en intervention de kinésithérapie, ergothérapie, orthophonie, psychomotricité et du service social ces besoins apparaissent différents, quantitativement et qualitativement à ce qui peut être trouvé dans d’autres équipes, en France ou dans d’autres pays de même niveau . Ces besoins avaient eux-mêmes été quantifiés à partir de l’analyse du fonctionnement du précédent SRPR (nombre d’interventions hebdomadaires et durée de ces interventions) Les effectifs recensés réellement dans le fonctionnement du SRPR sont rapportés aux effectifs considérés comme nécessaires.

La couverture médicale est évaluée pour chaque demi-journée des jours ouvrables. Pour la nuit, les week-ends et les jours fériés, sont comptabilisés les appels au service de réanimation de garde pour le SRPR, ainsi que les interventions médicales. Cette partie de l’indicateur est spécifique du programme de rééducation en post-réanimation.

L’enquête de satisfaction des patients et de leurs familles complètera cette évaluation par la mesure de la qualité perçue évaluée dans les trois mois qui suivent la sortie du SRPR. D’autres études se sont focalisées sur les soins intensifs et il est difficile de s’y référer pour le SRPR .

2.3.6

L’indicateur R 6

L’indicateur R 6, non spécifique, est lié aux bonnes pratiques de soins à travers les actions de formation et la rédaction de protocoles. A l’issu de cette étude, des indicateurs de résultats par rapport aux bonnes pratiques cliniques, devront compléter le présent travail d’évaluation réalisé sur l’organisation du SRPR.

2.3.7

L’indicateur R 7

L’indicateur R 7, permet de suivre la typologie des patients admis au SRPR à partir des chiffres issus du PMSI fournis par le département d’information médicale ; en cela, la méthode n’est pas spécifique du suivi d’un SRPR ( Tableau 1 ).