Alternatives to Replacement Arthroplasty for Glenohumeral Arthritis

William H. Paterson

Micah C. Hobbs

Sumant G. Butch Krishnan

Wayne Z. Burkhead

INTRODUCTION

Total shoulder arthroplasty has emerged as the gold standard for surgical treatment in the majority of patients with severe glenohumeral arthritis who have failed conservative management, with reported survivorship of 97% at 10 years.84 However, concern about potentially high rates of radiographic loosening of humeral (60%) and glenoid (76%) components has led the authors to recommend caution when considering total shoulder arthroplasty in patients under 50 years of age.84 Younger patients are also more likely to have complex causes of their glenohumeral arthritis, other than primary degenerative joint disease, which can contribute to less satisfactory outcomes after arthroplasty.74 Additionally, some patients have medical comorbidities severe enough to contraindicate glenohumeral replacement surgery. The treatment options for patients with glenohumeral arthritis (other than arthroplasty) include pain control with analgesic medications, physical therapy, corticosteroid and viscosupplement injections, arthroscopic debridement with or without biologic interposition resurfacing, glenoid and/or humeral osteotomy, glenohumeral arthrodesis, and resection arthroplasty. The treating physician’s challenge lies in choosing the treatment option most likely to diminish pain and restore function in each clinical situation.

Causes of Pain in Glenohumeral Arthritis

A primary consideration in selecting the appropriate management in these patients is the etiology of the arthritis. The results of the treatment are variable and depend on whether the patient has a diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis (OA) or inflammatory arthritis.

Osteoarthritis

Relatively little is known about the etiology and pathogenesis of primary OA. The radiographic findings present in OA result from the loss of articular cartilage with secondary changes in the bone80; however, the disease affects all periarticular soft tissues as well.13,52 Symptoms do not directly correlate with the radiographic changes of arthritis and depend on other factors such as patient psychological well-being and health status.21,23

The glenohumeral joint is an uncommon site of primary OA. Younger individuals often have a history of trauma related to their development of arthritis. Hovelius and Saeboe found that, after a single anterior dislocation, 18% of individuals developed moderate to severe glenohumeral arthropathy at 25-year follow-up.35 Samilson and Prieto devised a classification system for glenohumeral arthritis based on the

anteroposterior radiographic appearance of the shoulder in patients with a history of instability.75 Mild arthrosis is characterized by a less than 3-mm spur projecting off of the humerus, glenoid, or both. Moderate arthrosis displays osteophytes measuring between 3 and 7 mm off of the humerus, glenoid, or both, with some irregularity of the glenohumeral joint. Severe arthrosis is defined as the presence of osteophytes measuring greater than 7 mm off of the humerus, glenoid, or both, with joint space narrowing and sclerosis. This system has been shown to have excellent interobserver reliability.11

anteroposterior radiographic appearance of the shoulder in patients with a history of instability.75 Mild arthrosis is characterized by a less than 3-mm spur projecting off of the humerus, glenoid, or both. Moderate arthrosis displays osteophytes measuring between 3 and 7 mm off of the humerus, glenoid, or both, with some irregularity of the glenohumeral joint. Severe arthrosis is defined as the presence of osteophytes measuring greater than 7 mm off of the humerus, glenoid, or both, with joint space narrowing and sclerosis. This system has been shown to have excellent interobserver reliability.11

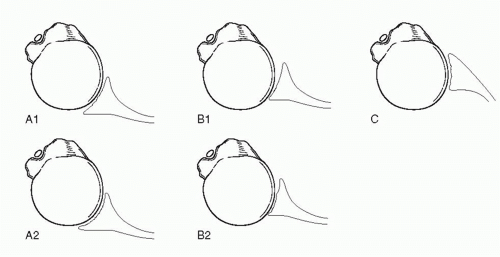

The classification system developed by Walch et al. has proven to be useful in the evaluation of morphologic changes of the glenoid associated with primary glenohumeral arthritis.92 Based on an evaluation of the axial cuts of computed tomography (CT) scans in 113 patients, three main types were found. Type A demonstrated symmetric erosion of the glenoid without associated humeral subluxation. In type B, posterior subluxation of the humerus with retroversion of the glenoid is present. If retroversion is greater than 25 degrees with a centered humeral head within the pathologic glenoid, typically the result of dysplasia, the glenoid is classified as a type C. Types A and B were divided into two subgroups, based on severity (Fig. 14-1).

Rheumatoid and Other Inflammatory Arthritides

The glenohumeral joint is commonly involved as part of the polyarthropathy affecting patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Laine et al. defined the spectrum of shoulder involvement in 277 hospitalized patients with RA.45 Glenohumeral arthritis was detected in 47.1% of patients, many of whom also had symptoms arising from other areas of the shoulder girdle. Of note, 16 (6%) patients, with a mean age of 31 years, had shoulder arthralgia without demonstrable roentgenographic changes. Similar to patients with OA, the destructive process in RA may be quite advanced before significant symptoms are noted. Petersson more recently documented that 91% of patients with RA reported shoulder problems.66 Thirty-one percent of these patients had such severe shoulder disability that they considered it to be their main problem. In addition to loss of motion, two common complaints in patients with RA are fatigue and muscle weakness. Rotator cuff defects are more common in this population than in patients with OA, occurring in approximately 26% to 52% of RA patients.18,29,58 In patients without a confirmed diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis, other similarly presenting disorders, such as synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, pseudogout, and the seronegative spondyloarthropathies (ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Reiter’s syndrome, psoriatic arthritis) should be considered. Many symptomatic patients with early stages of arthritis, regardless of etiology, appear to benefit from noninvasive forms of therapy.

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

Education

An initial discussion with the patient about the arthritic process and its probable future implications is a critical first step in the treatment. This helps to ensure that the patients’ expectations are consistent with their prognosis. Education also promotes compliance with the treatment regimen and avoidance of detrimental activities. The goals of treatment and anticipated improvements should also be made clear. Many patients will not be able to regain previous levels of sporting and other recreational activities. If a patient is a manual laborer, the early realization that he or she may be unable to continue that previous occupation will facilitate early retraining.

Patients with arthritis must be taught to interpret their symptoms in order to provide information important in determining appropriate therapy. Developing a sense of control over their symptoms fosters a patient’s active participation in the treatment and helps improve the psychological component of the effects of the disease. An insightful essay by R. E. Jones41 discusses the importance of the personality and manner of the physician, as well as the quality of the physician-patient relationship in determining patient satisfaction. Applying the basic principles discussed by Dr. Jones will help physicians teach their patients how to manage and best enjoy the highest quality of life that is possible through current operative and nonoperative interventions for their arthritic shoulders.

Physical Therapy

General Principles

Patients with decreased range of motion and strength associated with mild radiographic changes will benefit the most from physical therapy. However, almost all will experience some improvement in their symptoms.100 In some cases, especially

those patients with painful inflammatory arthropathies, a brief initial period of rest may be beneficial. Treatment with longer episodes of rest should be avoided, as it can contribute to muscle atrophy, joint contractures, and diminishing function. The aim of physical therapy is to increase range of motion and strength. However, therapy should not be considered as a failure if the result is only the maintenance of the existing range of motion. Exercises are designed specifically for the needs of each patient—this includes gentle passive motion and isometric resistance exercises, as well as an emphasis on strengthening of the scapular stabilizers. The scapulohumeral rhythm has been shown to be significantly altered in patients with glenohumeral arthritis.30 Correcting this abnormality will help reduce compressive and shear forces across the glenohumeral joint, thus reducing pain and further cartilage degeneration. Examples of specific exercises aimed at promoting range of motion include capsular stretching, wall walks, and pulley exercises. Exercises aimed at scapular stabilization include scapular pinches and scapular rows (Fig. 14-2). In patients who achieve an adequate painless range of motion, plyometric maneuvers are added (Fig. 14-3).

those patients with painful inflammatory arthropathies, a brief initial period of rest may be beneficial. Treatment with longer episodes of rest should be avoided, as it can contribute to muscle atrophy, joint contractures, and diminishing function. The aim of physical therapy is to increase range of motion and strength. However, therapy should not be considered as a failure if the result is only the maintenance of the existing range of motion. Exercises are designed specifically for the needs of each patient—this includes gentle passive motion and isometric resistance exercises, as well as an emphasis on strengthening of the scapular stabilizers. The scapulohumeral rhythm has been shown to be significantly altered in patients with glenohumeral arthritis.30 Correcting this abnormality will help reduce compressive and shear forces across the glenohumeral joint, thus reducing pain and further cartilage degeneration. Examples of specific exercises aimed at promoting range of motion include capsular stretching, wall walks, and pulley exercises. Exercises aimed at scapular stabilization include scapular pinches and scapular rows (Fig. 14-2). In patients who achieve an adequate painless range of motion, plyometric maneuvers are added (Fig. 14-3).

Although acting in nearly diametric ways, heat and cold are therapeutically useful when employed at appropriate times in chronic and acute phases of inflammatory pain. Cryotherapy is useful in the treatment of acute inflammatory flare-ups, such as in the postexercise state. Its analgesic effects have been attributed to the ability of cold to decrease the pain threshold by depressing the excitability of nerve fibers and muscle spindles.51 Cutaneous vasoconstriction and resulting reduction in blood flow reduce edema even in deeper tissues.

Heat, usually in the dry form, is more useful in the setting of chronic pain. Its mechanisms of action include temporizing pain and enhancing joint mobility by increasing tissue elasticity.49,50 Heat can be delivered superficially by using hot packs, hot water, or convective fluid therapy, while therapeutic ultrasound can be used for deeper penetration (see later section).

Hydrotherapy

The therapeutic efficacy of aquatic exercises cannot be overstated. This technique is invaluable in the rehabilitation of any glenohumeral joint, but especially in the setting of arthritis. Buoyancy helps reduce the stress exerted on the joint and surrounding musculature and can safely add resistance without using weights.83 The patient’s level of exertion can also be easily regulated by adjusting the speed of movement through water and, therefore, the resistance encountered. Additional alterations in water temperature and agitation enhance the beneficial effects of hydrotherapy.

Therapeutic Ultrasound

The clinical usefulness of therapeutic ultrasound is based primarily on its capacity to increase blood circulation and temperature in deep tissues. Tissue temperature can be elevated at depths up to 5 cm from the point of application on the patient’s skin, with temperatures peaking in the bone.52,53 When the treatment objective is to heat muscle tissue, the most effective modality currently available is shortwave diathermy.

These and other nonoperative therapeutic interventions are contraindicated in patients who have severe pain and a rapidly deteriorating condition. This scenario could imply concomitant occult sepsis, especially in the rheumatoid patient.

Occupational Therapy

Though in most patients suffering from glenohumeral arthritis the chief complaint is pain, the associated functional limitations are often a major concern. An impaired ability to dress and perform personal hygiene are particular problems. Occupational therapists can help these patients by providing assistive devices and by teaching alternative ways to accomplish these tasks. For patients who desire to continue their current employment, an analysis of specific job requirements is helpful in identifying and correcting problematic work practices.

Anti-inflammatory and Pain Medications

Oral analgesics, such as salicylates, acetaminophen, and codeine, can be very effective in treating arthritic pain. The role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in treating patients with symptomatic inflammatory arthropathies is well established.42 However, for use in OA, it is controversial whether NSAIDs are any better than simple analgesia.24 Nevertheless, a recent meta-analysis examining pain relief in patients with OA treated with NSAIDs versus acetaminophen, NSAIDs were statistically superior in providing relief of rest and walking pain.47 This study also found an increased, though not statistically significant, rate of discontinuation secondary to adverse events in the NSAID group. Recently introduced COX-2 specific inhibitors have produced controversy, both with regard to efficacy as well as potential for exacerbating medical comorbidities. The side effects of these medications are not insignificant. They may have deleterious effects on articular cartilage in addition to the risk of untoward effects on gastric, renal, and liver function, which are particular problems in elderly patients.24,25,42 Recent work in the peer-reviewed literature has demonstrated a significant reduction in risk of ulcer development by administering a proton-pump inhibitor with NSAID or COX-2 inhibitor in older patients and those with an ulcer history.76 Administration of opioids has recently been shown to result in significantly increased risks of cardiovascular events, fractures, and mortality than NSAIDs in elderly patients.82 These medications are not benign; physicians should seek to utilize any NSAID or other pain-relieving medication both judiciously and appropriately.

Nonoperative medical management of patients with intractable arthritic shoulder pain is difficult. A team approach may be necessary to provide adequate treatment of all factors affected by the disease. These specialists can manage depression, manipulate medication intake, inject trigger points, and perform nerve blocks. A neurologic workup may be necessary to rule out cervical radiculopathy, brachial plexopathy, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, or other disorders.

Corticosteroids

The diagnostic value of local anesthetic injections cannot be overstated and is a routine part of the initial patient workup. Appropriate steroid injections have also been documented to have significant therapeutic value.7,34 Although the use of intra-articular steroids can be effective in abating symptoms in joints afflicted with RA, they are generally of comparatively limited value in OA, typically providing short-term relief of symptoms. Judicious use of these injections is warranted based on their potentially detrimental effects.55

A prospective, randomized, blinded study by Dacre et al. evaluated the results of local steroid injections or physiotherapy in treating patients with painful or stiff rheumatoid shoulders.22 After controlling for age, gender, and disease severity, 60 consecutive patients were allocated into three groups to receive either local steroids, 6 weeks of physiotherapy, or both. Physiotherapy alone was just as effective as local steroid injections or a combination of these methods.

A recently published review of the peer-reviewed literature regarding the use of corticosteroid injections used for periarticular and intra-articular shoulder pain documented variable success.12 Anecdotally, we have found that, if a single intraarticular water-soluble corticosteroid injection is helpful, then another can be performed at a 6-month interval (no more often than two injections per year). If the first injection provides minimal relief (assuming a truly intra-articular position of the injection—if there is any doubt, fluoroscopic imaging should be considered), then further corticosteroid injections are likely to have little potential benefit.

Viscosupplementation

Intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid preparations have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of knee and hip OA. Recent studies have provided some evidence of possible chondroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of hyaluronic acid.2,36,37,63,94 Another study demonstrated that intra-articular hyaluronic acid actually increased joint swelling, inflammation, and cartilage damage late in the chronic phase of arthritis.72 Viscosupplementation of the glenohumeral joint has been shown to improve pain and function.6,8,73 There remains no peer-reviewed, double-blinded, prospective, randomized clinical trial documenting any benefit of such injections in patients with glenohumeral OA when compared to simple corticosteroid injections in the shoulder. Nevertheless, as with any other treatment modality, there may still be a benefit in certain patients who seek to avoid operative treatment for their glenohumeral arthritis. These indications have not yet been clarified.

Nutritional Supplements

Recently, many adjuvant nutritional supplements, or “nutraceuticals,” have been introduced for the amelioration of musculoskeletal complaints including arthritis. Animal work has demonstrated a reduction in the clinical, inflammatory, and histologic components of arthritis with the use of both glucosamine and chondroitin sulfates in combination. The apparent mechanism of glucosamine/chondroitin is to favorably shift cartilage biology toward matrix synthesis instead of degradation. Randomized controlled human studies have demonstrated conflicting results. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated no improvement in hip or knee arthritis symptoms and/or slowing of radiographic disease progression with glucosamine and/or chondroitin versus placebo.93 No peer-reviewed report has documented the efficacy of these substances in patients with isolated glenohumeral arthritis, though patients with concomitant arthritis in other joints have anecdotally reported an overall relief. The current available evidence does not support routine use of these supplements in the treatment of OA.

Authors’ Preferred Treatment Regimen

Any patient with pain and loss of function attributable to glenohumeral arthritis is begun on a trial of anti-inflammatory agents, activity modification, and physical therapy after the education process described above. In our practice, corticosteroid injections are very rarely utilized, as we have found appropriate physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications to be just as effective. If the patient continues to have pain after 6 weeks, we will change the anti-inflammatory medication and modify specific aspects of their physical therapy. If they develop progression of their arthritis characterized by further loss of motion and radiographic changes after completing this course of conservative therapy, nonoperative treatment is considered a failure and surgical management options are discussed.

OPERATIVE TREATMENT: ARTHROSCOPIC PROCEDURES

Arthroscopic Debridement

Arthroscopic debridement or lavage for arthritis has been successfully used in the weight-bearing joints of the lower limb, particularly the knee.40 In many cases, this may be the result of a strong placebo effect.57 Most orthopedic surgeons know of anecdotal evidence suggesting that arthroscopic debridement for glenohumeral arthritis can benefit some patients; however, the indications and benefits are less clear. In some cases, arthroscopy will reveal previously unrecognized significant glenohumeral joint degeneration.27 Cofield reported that, in eight patients with glenohumeral arthritis, the use of arthroscopy confirmed or modified the diagnosis, or altered the course of treatment, in all cases.16

Indications

Arthroscopic debridement may be considered for patients with mild to moderate glenohumeral joint disease without structural alteration of the joint. Those with mechanical symptoms secondary to loose bodies, or small lesions of the humeral head due to avascular necrosis, may also benefit. It is unlikely that any patient with severely limited motion or progressive joint alteration (such as biconcave glenoid erosion from OA) will benefit from simple debridement alone. There are several reported cases in which synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder, associated with arthritic changes, has been adequately treated by arthroscopic debridement.20,71,99

Surgical Technique

Standard glenohumeral anterior and posterior arthroscopic portals are utilized in either the beach-chair or lateral decubitus positions. While standard diagnostic glenohumeral arthroscopy is performed, special attention must be paid to the humeral and glenoid articular surfaces. Cartilaginous “lesions” or “flaps” should be gently debrided (often the use of a blunt-tip probe is enough) to prevent mechanical engagement. Exposed bony lesions should be identified and possibly considered for procedures such as microfracture or abrasion arthroplasty. The recess behind the subscapularis tendon (subcoracoid bursa) and the axillary pouch (both anterior and posterior) should be carefully examined for loose bodies. Osteophytes can be removed from the inferior portion of the humeral head.

Postoperative Management

Immediate motion is paramount, and a sling should be used for no longer than one night (if used at all). Immediate physical therapy exercises emphasizing motion in external rotation and forward flexion are undertaken.

Results of Arthroscopic Debridement

Generally, results of arthroscopic debridement for OA of the shoulder depend on the extent of degenerative changes.60,61 and 62,90 Ogilvie-Harris and Wiley reviewed 54 patients with OA of the shoulder who were followed for 3 years.62 When degenerative changes were limited to the superficial articular cartilage, a successful outcome occurred in two-thirds of cases; however, when changes were associated with exposure of subchondral bone, a successful outcome occurred in only onethird of patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree