Adolescent and Pediatric Problems

16.1 Spondylolysis

Prim Care 2005;32:201; Ortho Clin North Am 2003;34:461; Phy Sportsmed 2001;29:27; Phy Sportsmed 1996;24:57; Clin Sports Med 1993;12:517

Cause: Fracture of pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine.

Epidem: Prevalence 5% in general population; 43% of LBP in adolescents; 63% among divers; 36% in weight lifters; 33% in wrestlers; 32% in gymnasts; 23% in track and field; 85-90% at L5 and 5-15% at L4.

Pathophys:

Functional anatomy: the pars interarticularis is the bridge of bone between the superior and inferior facets; the pars is stressed by hyperextension activities.

These are thought to be stress fractures, but may exist congenitally.

Sx: Back pain aggravated by extension activity (arching back in volleyball, weight lifting, running downhill, the follow-through in a rowing stroke); usually not associated w radicular symptoms.

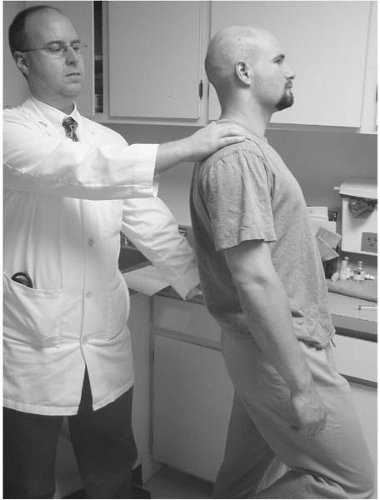

Si: Usually without palpable back pain; may have tight hamstrings; pain w standing single leg hyperextension (stork test)—pt standing with examiner behind, pt stands on one leg and the examiner

assists as the pt hyperextends over the stance leg; pos is unilateral exacerbation of pain on the affected side; no palpable bony tenderness (Figure 16.1).

assists as the pt hyperextends over the stance leg; pos is unilateral exacerbation of pain on the affected side; no palpable bony tenderness (Figure 16.1).

Crs: Progressive worsening of pain w activity.

Cmplc: Spondylolisthesis (see 16.2).

X-ray:

Plain film oblique view demonstrating lucent line in the neck of the “Scotty dog.”

Bone scan may demonstrate focal signal in the pars.

SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography) done with the bone scan is very specific in identifying pars lesion.

Rx:

Relative rest for 4-6 wk from offending activity avoiding hyperextension and high impact activity.

Pain control with ice/heat/NSAIDs.

Physical therapy focused on hamstring flexibility and abdominal muscle strengthening. Once pain free, may cross train w low impact (bike, swim, deep water run, stairmaster) aerobics and LE wt lifting.

If sx persist or return early consider longer restriction or immobilization in a TLSO (thoracolumbar spinal orthosis) brace with monthly follow-up. Bracing is discontinued when pt is pain free with daily activities and has a nl exam. At this point, therapy is started for strengthening and stabilization.

There are arguments that bracing should be the initial treatment for all pts; studies have shown radiographic healing of acute lesions w bracing and activity restriction.

Refer to orthopedics or a spine specialist for refractory cases of pain despite adequate immobilization, signs of infection or HNP.

Return to Activity: Full ROM with neg stork test; return to impact activity slowly monitoring pain.

16.2 Spondylolisthesis

Prim Care 2005;32:201; Ortho Clin North Am 2003;34:461; Clin Sports Med 2002;21:133; The Low Back Pain Handbook. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, Inc. 1997;331; Pediatric and Adolescent Sports Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1994;164

Cause: Anterior slippage of spine.

Epidem:

50% of those with bilateral pars defects will develop anterior slippage.

90% at L5-S1.

Runs in families.

Slippage usually occurs between 9-13 yr.

Pathophys:

Anterolisthesis involves the anterior movement of the overlying vertebral body on the affect body ie, L5 on S1.

Causes include bilateral spondylolysis, pars elongation from healed stress fractures, degeneration (seen in the elderly).

Classification:

Grade 1: <25% anterior slippage

Grade 2: 25-50%

Grade 3: 50-75%

Grade 4: >100%

Sx: Pain below the beltline aggravated by twisting, extension, or prolonged standing.

Si: May have a “waddling” gait; hamstring tightness, hyperlordosis, pain with extension (stork test, see 16.1); may have neurologic findings (rare, but usually in L5 or S1 distribution); in severe cases of slippage, may palpate a step-off in the spinous processes.

Crs: Variable, but progressive pain with more advanced and progressive slips.

X-ray: Lateral L-spine demonstrating anterior slip of one vertebrae on the other.

Rx:

Asymptomatic:

<25%: no restrictions on activity with exam and lateral L-spine film every 6-12 mo through growth period.

25-50%: restrict from collision sports or high-risk activities involving hyperextension or high impact.

>50% or w progression, surgical stabilization.

Symptomatic (pain):

<25%: activity restriction and pain control; part-time bracing, if needed w gradual wean and return to activities when pain free.

25-50%: rest and bracing (Boston anti-lordotic); counseling against returning to high-risk activities.

>50%: surgery; other indications for surgery include pain >6-12 mo unrelieved by rest or immobilization with any grade, progressive slip, neurologic symptoms.

Return to Activity: Good hamstring flexibility; no pain with single leg hyperextension; pt and parents understand risks and will return if increasing symptoms.

16.3 Scheuermann’s Kyphosis

Campbell’s Operative Orthopedics. 10th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2003;1878; Clin Sport Med 2002;21:133

The Low Back Pain Handbook. St. Louis: Mosby, 1997;336; Major Prob Ped 1986;28:52; Pediatric and Adolescent Sports Medicine. WB Saunders 1994;170

Cause: Wedging of 3 or more consecutive vertebrae of at least 5° and or kyphosis >35°.

Epidem: 0.4-8.3% of population; most common in boys 13-17 y/o; classic Sheuermann’s occurs between T7-T10.

Pathophys:

Functional anatomy:

Lumbar and thoracic vertebral end plates (epiphyses) above and below each vertebral body.

Developmental collapse of this epiphysis.

Schmorl’s nodes.

May be anterior or central.

Represent herniation of nucleus pulposis through the end plate.

Sx: Back pain with forward bend; may be nonpainful.

Si: Increased thoracic kyphosis; normal neuro exam.

Crs: Progression is variable.

Cmplc: Chronic pain and deformity (kyphosis).

Diff Dx: Compression fracture, postural problem (round back), discitis, tumor, osteomyelitis.

X-ray: Irregular vertebral end plates, Schmorl’s nodes, anterior wedging >5° of 3 or more consecutive thoracic vertebrae or one or more in thoracolumbar Scheuermann’s.

Rx:

Kyphosis <50% without progression:

Follow-up x-ray every 4-6 mo.

Emphasis on stretching hamstring and pectoralis muscles, lumbar flexion exercises, and spine extensor strengthening.

Kyphosis >50° brace (TLSO or Milwaukee Brace) worn 16-18 hr/d; low-risk activities are encouraged and can be done w/o brace.

Surgery if deformity not controlled with bracing or a rigid kyphosis >80°.

Referral for all cases >35° is prudent.

Return to Activity: Pain-free ROM; no sport activity for 1 yr after surgical fusion for more advanced cases.

16.4 Osteochondritis Dessicans of the Knee (OCD)

Prim Care 2005;32:253; Ortho Clin North Am 2003;34:341; Grainger & Allison Diag Rad 4th ed: London; Churchill Livingstone, Inc. 2001; 2040; Phy Sportsmed 1998;26:31; Clin Sports Med 1997;16:157; Pediatr Clin No Am 1996;43:1067; Sports Medicine: The School-Age Athlete. 2nd ed: Philadelphia; WB Saunders 1996;273

Cause: Cause is currently thought to be multifactorial.

Epidem:

Approximately 15-30 cases per 100,000.

Most frequently between 13 to 21 y/o.

Males are affected at least twice as often as females.

Bilateral in 20-30% of cases.

Juvenile and adult onset:

Pathophys:

Exact pathophysiology unknown. The five suggested theories are ischemia, genetic predisposition, abnormal ossification, trauma, and cyclical strain.

Regardless of the cause the result is a partial or complete separation of a segment of normal hyaline cartilage.

The plane of separation varies, but is most commonly just below the subchondral plate, creating an osteochondral fragment.

Typically lesions progress through 4 stages. Intervention at any stage can arrest the process. Staging based on MRI imaging:

Stage 2: partially detached; osteochondral fragment.

Stage 3: defect is detached/loose but within underlying cartilage.

Stage 4: defect detached and migrated.

About 80-85% of cases occur on the medial condyle with the majority classically located on the lateral aspect within the intercondylar notch. The lateral femoral condyle and patella are less commonly affected.

Sx:

Knee pain, often vague and diffuse.

Intensity of pain often related to activity level often w swelling.

If a loose body is present pts may present w catching, locking, or giving way.

Si: May or may not have effusion; thigh atrophy and pos meniscal tests.

Crs:

The prognosis varies.

In situ lesions may heal spontaneously or progress to eventually become dislodged, forming a loose body within the joint.

Cmplc: OCD in adults is more likely to progress to OA, intra-articular loose bodies, chronic pain, and disability.

Diff Dx: Fracture, neoplasm, ligamentous injury, meniscal injury (see 11.3), retropatellar knee pain (see 11.8).

X-ray:

Well-delineated lesion in the subchondral bone best seen on tunnel view.

Bone scans can help with establishing a diagnosis and prognosis since a relationship exists between radionuclide uptake and healing potential.

MRI is particularly helpful in distinguishing between Stage 2 and 3 lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree