Acute Repair and Reconstruction of Sternoclavicular Dislocation

Steven P. Kalandiak

Edwin E. Spencer Jr.

Michael A. Wirth

Charles A. Rockwood

DEFINITION

Sternoclavicular dislocation is one of the rarest dislocations but one most shoulder surgeons will encounter several times during a career (more so if they are in a practice with significant exposure to high-energy trauma).

Sternoclavicular dislocations represented 3% of a series of 1603 injuries of the shoulder girdle reported by Cave.9

The true ratio of anterior to posterior dislocations is unknown because most reports focus on the rarer posterior type. Estimates range from a ratio of 20 anterior dislocations to each posterior by Nettles and Linscheid,22 in a series of 60 patients (57 anterior and 3 posterior), to a ratio of approximately 3:1 (135 anterior and 50 posterior) in our series29 of 185 traumatic sternoclavicular injuries.

Not all sternoclavicular dislocations require surgery. Avoiding inappropriate patient selection, preventing hardware-related complications, and repairing or reconstructing the capsule and the rhomboid ligament if the medial clavicle has been resected require special emphasis.

Although this region can be intimidating because of the surrounding anatomic structures, a knowledgeable and careful surgeon can treat this joint safely and reliably produce good results.

ANATOMY

The epiphysis of the medial clavicle is the last epiphysis of the long bones to appear and the last to close. It does not ossify until the 18th to 20th year, and it generally fuses with the shaft of the clavicle around age 23 to 25 years.17,18 For this reason, many sternoclavicular “dislocations” in young adults are in fact physeal fractures.

The articular surface of the medial clavicle is much larger than that of the sternum. It is bulbous and concave front to back and convex vertically, creating a saddle-type joint with the curved clavicular notch of the sternum.17,18

A small facet on the inferior aspect of the medial clavicle articulates with the superior aspect of the first rib in 2.5% of subjects.8

There is little congruence and the least bony stability of any major joint in the body. Almost all of the joint’s integrity comes from the surrounding ligaments.

Ligaments

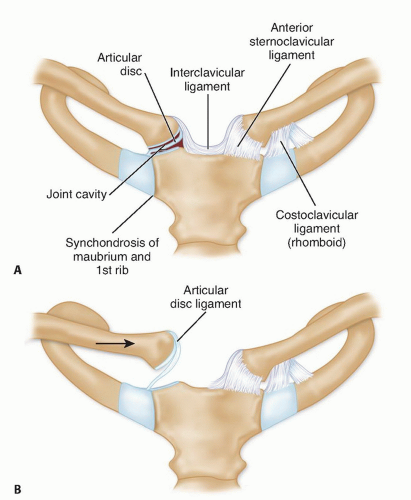

The intra-articular disc ligament is dense and fibrous, arises from the synchondral junction of the first rib to the sternum, passes through the sternoclavicular joint, and divides it into two separate spaces17,18 (FIG 1). It attaches on the superior and posterior medial clavicle and acts as a checkrein against medial displacement of the inner clavicle.

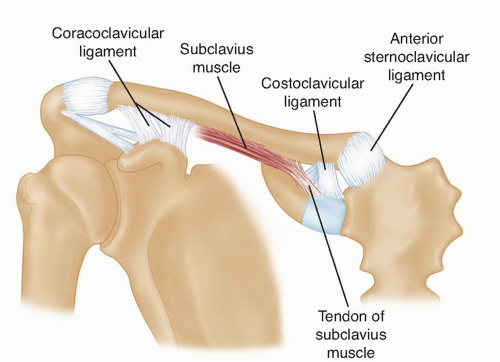

The costoclavicular (rhomboid) ligament attaches the upper surface of the medial first rib and upper surface of the first costal cartilage and to the rhomboid fossa on the inferior surface of the medial end of the clavicle.17,18 It averages 1.3 cm long, 1.9 cm wide, and 1.3 cm thick.8

The anterior fasciculus arises anteromedially, runs upward and laterally, and resists lateral displacement and upward rotation of the clavicle.

The interclavicular ligament (see FIG 1) connects the supero-medial aspects of each clavicle with the capsular ligaments and the upper sternum. Comparable to the wishbone of birds, it helps the capsular ligaments to produce “shoulder poise”; that is, to hold up the lateral aspect of the clavicle.18

The capsular ligaments cover the anterosuperior and posterior aspects of the joint and represent thickenings of the joint capsule (see FIGS 1 and 2). The clavicular attachment of the ligament is primarily onto the epiphysis of the medial clavicle, with some blending of the fibers into the metaphysis.5,11

In sectioning studies, the capsular ligaments are the most important structures in preventing upward displacement of the medial clavicle caused by a downward force on the distal end of the shoulder.3

This lateral poise of the shoulder (ie, the force that holds the shoulder up) is attributed to a locking mechanism of the ligaments of the sternoclavicular joint.

Other single ligament sectioning studies32 have shown that the posterior capsule is the most important primary stabilizer to anterior and posterior translation. The anterior capsule is an important restraint to anterior translation. The costoclavicular ligament is unimportant if the capsule remains intact,32 although it may be an important secondary restraint if the capsular ligaments are torn, much like the coracoclavicular ligament laterally.

Applied Surgical Anatomy

A “curtain” of muscles—the sternohyoid, sternothyroid, and scalenus—lies posterior to the sternoclavicular joint and the inner third of the clavicle and blocks the view of vital structures —the innominate artery, innominate vein, vagus nerve, phrenic nerve, internal jugular vein, trachea, and esophagus. A recent anatomic study demonstrated that the closest is the brachiocephalic vein, at an average distance of 6.6 mm.24

The anterior jugular vein lies behind the clavicle and in front of the curtain of muscles. Variable in size and as large as 1.5 cm in diameter, it has no valves and bleeds like someone has opened a floodgate when nicked.

The surgeon who is considering stabilizing the sternoclavicular joint by running a pin down from the clavicle into the sternum should not do it and should remember that the arch of the aorta, the superior vena cava, and the right pulmonary artery are also very close at hand.

PATHOGENESIS

Most sternoclavicular joint dislocations result from high-energy trauma, usually a motor vehicle accident. They occasionally result from contact sports.

A force applied directly to the anteromedial aspect of the clavicle can push the medial clavicle back behind the sternum and into the mediastinum.

More commonly, a force is applied indirectly, from the lateral aspect of the shoulder. If the shoulder is compressed and rolled forward, a posterior dislocation results; if the shoulder is compressed and rolled backward, an anterior dislocation results.

As noted earlier, many injuries of the sternoclavicular joint in patients younger than 25 years are, in fact, fractures through the medial physis of the clavicle.

NATURAL HISTORY

Mild or moderate sprain

The mildly sprained sternoclavicular joint is stable but painful.

The moderately sprained joint may be slightly subluxated anteriorly or posteriorly and may often be reduced by drawing the shoulders backward as if reducing and holding a fracture of the clavicle.

Anterior dislocation

Although most anterior dislocations are unstable after closed reduction, we still recommend an attempt to reduce the dislocation closed.

Occasionally, the clavicle remains reduced, but typically, the clavicle remains unstable after closed reduction. We usually accept the deformity because an anteriorly dislocated sternoclavicular joint typically becomes asymptomatic, and we believe that the deformity is less of a problem than the potential complications of operative fixation.

When the entire medial clavicle is stripped out of the deltotrapezial fascia, the deformity can be so severe that it may be poorly tolerated, so we consider primary fixation. In those rare cases when a chronic anterior dislocation is symptomatic, one may perform a capsular reconstruction or a medial clavicle resection and costoclavicular ligament reconstruction.

Posterior dislocation

In contrast to anterior dislocations, the complications of an unreduced posterior dislocation are numerous: thoracic outlet syndrome, vascular compromise, and erosion of the medial clavicle into any of the vital structures that lie posterior to the sternoclavicular joint.

Closed reduction for acute posterior sternoclavicular dislocation can usually be obtained, and the reduction is generally stable. Often, general anesthesia is necessary. However, when a posterior dislocation is irreducible or the reduction is unstable, an open reduction should be performed.

When chronic posterior dislocation is present, late complications may arise from mediastinal impingement, so we recommend medial clavicle resection and ligament reconstruction.

Physeal injuries

The typical history for physeal injuries is the same as for other traumatic dislocations. The difference between these

injuries and pure dislocations is that most of these injuries will heal with time, without surgical intervention.

In very young patients, the remodeling process can eliminate deformity because of the osteogenic potential of an intact periosteal tube. Zaslav et al,39 Rockwood and Wirth,29 and Hsu et al19 have all reported successful treatment of displaced medial clavicle physeal injury in adolescents and provided radiographic evidence of remodeling.

Anterior physeal injuries may be reduced, but if reduction cannot be obtained, they can be left alone without problem. Posterior physeal injuries should likewise undergo an attempt at reduction. If a posterior dislocation cannot be reduced closed and the patient is having no significant symptoms, the displacement can be observed while remodeling occurs. Even in older individuals, a posteriorly displaced fracture with moderate displacement and no mediastinal symptoms may be observed, as it usually becomes asymptomatic with fracture healing.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A history of high-energy trauma is almost a requirement for the diagnosis. Most cases will be due to a motor vehicle accident, a fall from a significant height, or a sports injury.

The absence of such a history suggests either an atraumatic instability or some other atraumatic condition of the joint.

Posterior displacement may be obvious, but anterior fullness can represent either anterior displacement or swelling overlying posterior displacement.

Careful examination is extremely important. Mediastinal injuries may occur when a traumatic dislocation is posterior, and the physician should seek evidence of damage to the pulmonary and vascular systems, such as hoarseness, venous congestion, and difficulty breathing or swallowing.

Evaluation should also include the remainder of the thorax, shoulder girdle, and upper extremity as well as the contralateral sternoclavicular joint.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs

Occasionally, routine anteroposterior chest radiographs suggest displacement compared with the normal side. However, these are difficult to interpret.

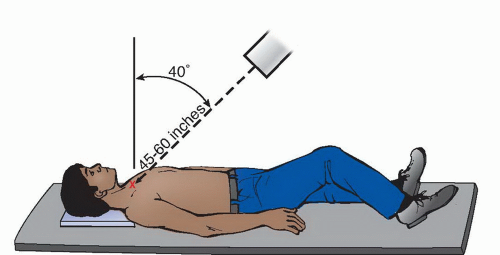

Serendipity view: A 45-degree cephalic tilt view is the most useful and reproducible plain radiograph for the sternoclavicular joint. The tube is centered directly on the sternum and a nongrid 11 × 14 cassette is placed on the table under the patient’s upper shoulders and neck, so the beam will project the medial half of both clavicles onto the film (FIG 3). The technique is the same as a posteroanterior view of the chest.

An anteriorly dislocated medial clavicle will appear to ride higher compared to the normal side. The reverse is true if the sternoclavicular joint is dislocated posteriorly (FIG 4).

More recently, ultrasound has been proposed as an alternate method of making the initial diagnosis of sternoclavicular dislocation.4

In the past, tomograms were useful in distinguishing a sternoclavicular dislocation from a fracture of the medial clavicle and defining questionable anterior and posterior injuries of the sternoclavicular joint. Although they provide more information than plain films, at present, they have been replaced with computed tomography (CT) scans.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree