Acromioplasty, Distal Clavicle Excision, and Posterosuperior Rotator Cuff Repair

Robert J. Neviaser

Andrew S. Neviaser

DEFINITION

Posterosuperior tears of the rotator cuff involve the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and occasionally the teres minor.

Some of the surgical techniques to be described here are no longer commonly used, as the majority of surgeons repair most tears using arthroscopic approaches.

These approaches, however, are still useful for treating those massive tears that may need special procedures to accomplish the repair.

ANATOMY

The rotator cuff is a group of four musculotendinous structures arising from the scapula: the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus, the teres minor, and the subscapularis. The first three insert on the greater tuberosity of the humerus, whereas the subscapularis inserts on the lesser tuberosity. The cuff muscles not only rotate the humerus at the glenohumeral joint but also act to keep the humeral head centered in the glenoid fossa, providing a fixed fulcrum for the arm to be elevated, primarily by the deltoid. The subacromial bursa overlies the tendons.

These structures, in turn, sit under the coracoacromial arch, which consists of the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament, and the outer end of the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint.

The three parts of the deltoid arise from the acromion and lateral clavicle, and this muscle lies over the cuff and bursa. It acts to elevate, abduct, and extend the humerus at the shoulder joint.

PATHOGENESIS

Rotator cuff tears have a multifactorial pathogenesis.

Among the factors are tendon insertional degeneration (enthesopathy), shear (the inferior third of the cuff tendons being more susceptible to shear failure than the superior two-thirds), hypovascularity, impingement, and microtrauma.

Although impingement was felt to be the sole underlying cause of cuff disease for some time, it is now felt to be a secondary factor in that it likely comes into play once the cuff is weakened and is unable to balance the upward pull of the deltoid. This then brings the cuff into contact with the undersurface of the anteroinferior acromion and the rest of the coracoacromial arch.

Major injury is uncommonly a factor and usually involves an already degenerative tendon. A common major injury, which can result in a rotator cuff tear, is a primary, or a first-time, anterior dislocation of the shoulder in a patient older than age 40 years. The older the patient, the more likely there is a cuff tear.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of rotator cuff tears is unknown. There have been several studies in cadavers and by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that have confirmed that the incidence of asymptomatic cuff tears over the age of 60 years is around 33%. These subjects have been pain-free and fully functional.

Any study that has tried to follow asymptomatic tears prospectively over time has suffered from an unacceptably high loss of patients being followed, thereby negating any conclusions.

The condition of cuff tear arthropathy does not occur regularly with known cuff tears, even massive ones.

It has been shown that after a traumatic tear, the outcome is influenced by the time interval to repair—in other words, those repaired within the first 3 weeks do better than those repaired between 3 and 6 weeks, and those older than 6 weeks do even worse. These outcomes apply only to the uncommon traumatic tear, not to the far more common degenerative type.

Therefore, treatment should be based purely on the presenting symptoms of pain and functional limitation, not on the possibility that a tear may progress in size or develop into cuff tear arthropathy, because the latter possibilities cannot be predicted.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Barring the unusual history of a significant injury, such as a primary anterior glenohumeral dislocation over the age of 40 years resulting in a traumatic tear, most patients will present with a complaint of pain of indeterminate onset.

The pain is often worse at night and with use, especially overhead activity.

Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may provide some temporary relief, as may stretching.

The pain can radiate to the lateral humerus, but not to below the elbow or into the neck and occiput.

There rarely will be significant motion loss (ie, motion will be unaffected) nor will the patient often notice weakness.

The first step in the physical examination is to examine the neck to eliminate that as a source of the pain.

One should inspect the shoulder for atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus or rupture of the tendon of the long head of the biceps, which usually occurs with a large or massive tear. One should also palpate the region of the greater tuberosity and the bicipital groove for tenderness. In thin patients, it is possible to feel the cuff defect through the skin and deltoid.

Motion is assessed by having the patient elevate the arms actively and comparing this to passive motion and by placing the arms in 90 degrees of abduction and maximal external rotation as well as maximal external rotation with the arm at the side.

The inability to hold the arm in maximum active external rotation in abduction or at the side is a positive lag sign, indicating a major defect in the musculotendinous unit.

Internal rotation is evaluated by having the patient reach up the back to the highest point possible. Further testing for this (subscapularis function) is discussed in another chapter.

Strength of the external rotators is tested with the arm at the side and in maximal external rotation by having the patient resist a force directed toward the body. Strength in elevation is assessed by resisting the patient’s attempt to raise the arm.

Provocative signs for cuff and biceps disease include the following:

Impingement sign: Forcing the fully forward elevated arm against the fixed scapula helps to localize the finding to the rotator cuff when the patient experiences pain.

Palm-down abduction test: By internally rotating the arm, the supraspinatus and anterior infraspinatus tendons are placed directly under the coracoacromial arch. Elevating the arm in the scapular plane when it is in internal rotation compresses these tendons against the undersurface of the acromion.

Biceps resistance test (Speed test): Pain during this maneuver indicates involvement of the long head of the biceps tendon.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

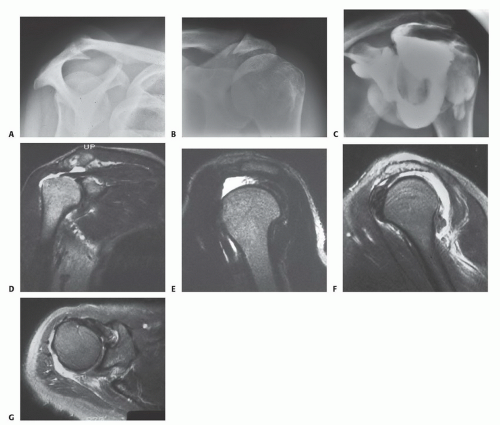

Standard radiographs, including anteroposterior (AP) views in internal and external rotation, an axillary view, and an outlet view, should always be taken to look for the type of acromion (FIG 1A), acromioclavicular joint changes, and narrowing of the acromial-humeral interval (FIG 1B) and to rule out other conditions.

Additional preoperative studies include MRI, ultrasound, or arthrography.

Ultrasound is institutional-specific and operator-dependent, so its use is limited to centers with institutional expertise.

Arthrography once was the gold standard but now is used only under rare circumstances (ie, when an MRI cannot be done). It can show a full-thickness cuff tear (FIG 1C) but requires an intra-articular injection with fluoroscopy and radiography.

The most commonly used study is an MRI. It not only shows the integrity of the tendons but also provides a three-dimensional view of the cuff (FIG 1D-G). This capacity makes the MRI a versatile preoperative planning tool.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cuff tendinitis without tear

Incomplete rotator cuff tear

Bicipital tendinitis

Calcific tendinitis

Suprascapular neuropathy

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

If there is a history of an acute injury with immediate inability to raise the arm, the patient can be treated symptomatically and followed every 5 to 7 days for the first 2 weeks. If the ability to raise the arm does not recover, then nonoperative treatment should be abandoned and surgery undertaken.

The objective of treating rotator cuff disorders, in the absence of an acute injury with immediate loss of elevation, is primarily to relieve pain and secondarily to restore function or strength. Pain relief is a more predictable outcome of treatment than is restoration of function or strength. Therefore, nonoperative treatment should be directed at relieving pain.

Although NSAIDs can help with pain, a subacromial steroid injection is often more effective and immediate in its relief.

Once the pain is improved, physical therapy should be instituted. This involves two aspects: stretching and strengthening of the rotators and elevators.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

As noted earlier, in the unusual case in which there is an acute injury resulting in an immediate loss of elevation of the arm, if symptomatic treatment fails to restore the ability to raise the arm, surgical repair should be undertaken before the 3-week mark.

For the more common chronic attritional tear, surgery is considered if an injection, NSAIDs, and physical therapy fail to produce a level of pain relief and function that is acceptable to the patient.

Patients make the decision to have surgery based on whether they can live with the pain and functional limitation that they have. They need to understand that the operation can help them but can also leave them unchanged or worse.

Preoperative Planning

The radiographs and MRI should be reviewed preoperatively.

The radiographs will help in planning the need for and extent of acromioplasty.

The MRI will show which tendons are torn and the degree to which they are torn or retracted. It will also show the presence or absence of fatty infiltration of the muscles.

Positioning

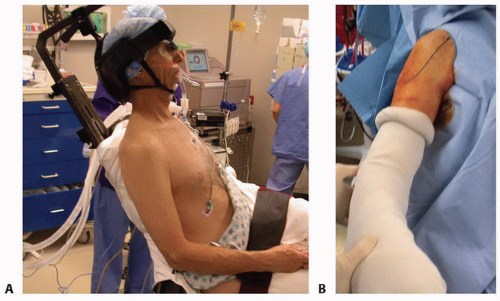

The patient is positioned in a sitting position, even more upright than the so-called beach-chair position (FIG 2A). The arm is draped free to allow uninhibited mobility of the extremity (FIG 2B).

This allows the surgeon to look down on the cuff from above, therefore, being able to see posterosuperiorly as well as superiorly and anteriorly. It also permits better access to the posterior part of the infraspinatus and the teres minor.

Approach

There are basically three approaches to cuff repair:

The all-arthroscopic approach (discussed in another chapter)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree