Acromioclavicular Joint Arthritis

Joseph A. Abboud

William J. Warrender

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Osteoarthritis of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint is a common source of shoulder pain that is often neglected by physicians. Patients typically present with shoulder pain that unfortunately is not well localized to the AC joint; there is usually a dull ache involving the deltoid area that is exacerbated by motion.1 Although most planes of motion will cause the patient pain, horizontal cross body adduction (such as occurs when reaching over the front of the body) will tend to be the most symptom provoking. Patients will also often complain of an inability to sleep on the affected side; this vague description of pain is likely due to irritation of the underlying subacromial bursa by inferior-projecting osteophytes from the AC joint.2

CLINICAL POINTS

Shoulder pain on the top of the shoulder is a common symptom.

Shoulder movement, especially in a horizontal direction, aggravates the pain.

Typical complaints include inability to sleep on the affected side.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The clinical presentation of AC osteoarthritis can be deceiving even to experienced physicians.

A careful examination of the cervical spine should be performed to rule out any abnormalities, including radiculopathy and degenerative joint disease that may cause referred pain in the shoulder.

The shoulder is inspected and palpated, and the muscle strength as well as the range of motion is assessed.

Range of motion of the shoulder is performed actively and passively and compared with that of the asymptomatic side.3 This may reveal joint prominence or asymmetry. Range of motion tends to vary greatly, as there may be coexisting rotator cuff or capsule pathology.

Overall, most patients should have nearly full but painful passive range of motion. It is common for a painful are in a range greater than that associated with rotator cuff impingement to be present (i.e., pain in the 120- to 180-degree vs. 60- to 120-degree range).1

Pain is usually reliably reproduced with passive horizontal cross body adduction at 90 degrees of forward flexion. While the patient is in a sitting position, the examiner passively forward flexes the arm to 90 degrees and then horizontally adducts the arm as far as possible. A positive test results in localized pain over the AC joint (see Fig. 36-2) and is fairly specific for AC joint pathology.4

In addition, direct manual pressure by the examiner on the superior surface of the AC joint should reproduce the patient’s symptoms. A significant difference should be noted between the injured and noninjured sides.

The active compression test of O’Brien assists in excluding labral (superior labral anterior posterior [SLAP]) pathology

as a possible pain generator (see Fig. 35-16); the patient forward flexes the arm to 90 degrees with the elbow fully extended and adducted 15 degrees medial to the midline of the body with the thumb pointed downward. The examiner then applies a downward force to the arm while the patient resists. In the next position, the test is repeated with the arm in the same position, but the patient fully supinates with the palm facing the ceiling. If pain is produced in the first position and is reduced or eliminated in the second, a superior labral injury is favored over AC joint pathology and vice versa.4

STUDIES (LABS, X-RAYS)

Laboratory studies are generally not helpful in the diagnosis of AC joint arthritis.

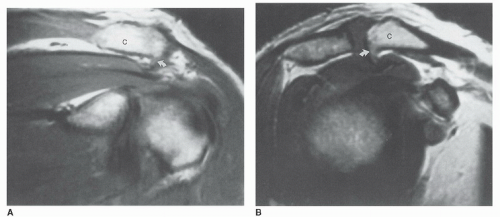

FIGURE 38-2. Oblique coronal (A) and oblique sagittal (B) images of the AC joint demonstrate a large spur (white arrows) on the undersurface of the distal clavicle. (C: clavicle.) (From lannotti JP, Williams GR. Disorders of the Shoulder: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:915.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|