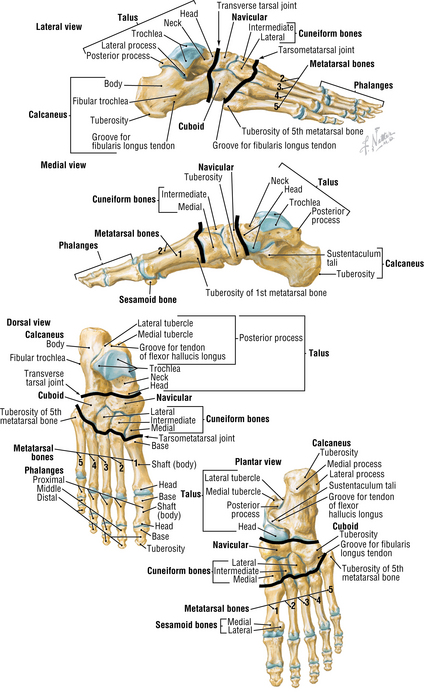

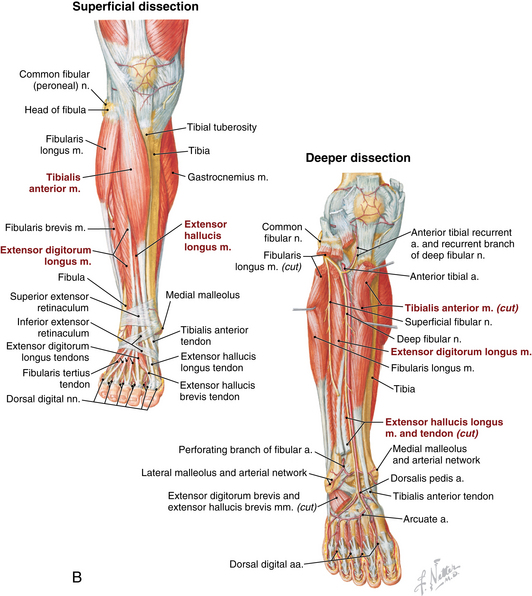

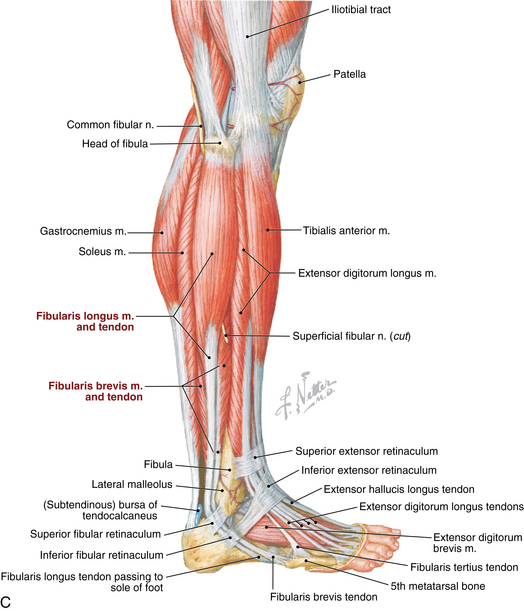

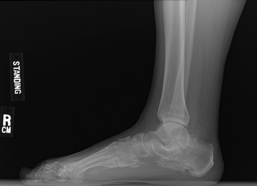

8 Foot and ankle Figure 8-3. Dorsal view of the foot sole. (From Netter illustration from www.netterimages.com. Copyright Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.) Figure 8-4A-B. Plantar views of the foot muscles. (From Netter illustration from www.netterimages.com. Copyright Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.) Table 8-2. Normal Ankle/Foot Range of Motion Table 8-4. • Generally has limited value and indicated only in mild arthritis without significant joint space narrowing • Indications: painful tibiotalar arthritis not responsive to nonoperative treatment, failed arthroplasty • Contraindications: acute infection, acute neuropathic arthropathy, severe vascular disease • Indications: tibiotalar arthritis not responsive to nonoperative management, low demand patients older than age 50-55 years, weight < 200 lb, maintained range of motion, normal/near normal alignment, no preexisting subtalar arthritis. • Contraindications: acute infection, significantly diminished bone stock, neuropathy, severe vascular disease. Relative contraindications include deformity greater than 5 degrees and talar avascular necrosis. • Major risks include nonunion (<10%), wound complications, nerve injury, infection, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), hardware loosening/failure, and development of arthritis in hindfoot/subtalar joint. A risk of amputation exists in cases of severe complication (≤5%). • The complication rate increases with nicotine use, neuropathy, and vascular disease. • Informed consent and counseling: Risks are similar to arthrodesis (infection, wound complications, DVT, hardware loosening). Recent studies report 10% to 30% reoperation rate and survival rates of 77% to 90% at 5- and 10-year follow-up. If surgery fails, consider conversion to arthrodesis (contraindicated in infection). Limited revision options are available. Figure 8-8. Postoperative anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) views following ankle arthrodesis using anterior plate. • Many implants for fixation are available, the most common being an anterior plate with cross-screws. An intraoperative radiograph is used to confirm appropriate placement. • Open anterior approach is most common. An incision is made over the ankle between anterior tibial tendon and extensor hallucis longus (EHL). • Structures at risk include superficial peroneal nerve and neurovascular bundle (posterior to EHL). • The neurovascular bundle is mobilized, and the tibial osteophytes are removed to visualize joint. The joint is prepared by removing any remaining articular cartilage, and microfracturing and/or drilling the subchondral bone. A lamina spreader can be helpful for visualization. • Align neutral dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, 0 to 5 degrees hindfoot valgus, 5 degrees external rotation. An intraoperative radiograph is used to determine correct alignment for fixation. • A sugar tong splint is applied in the operating room after closure. The patient remains non–weight bearing. • Sutures are removed and radiographs are obtained. A non–weight-bearing cast is applied for 4 weeks. • Radiographs reviewed. The patient is transitioned to a weight-bearing cast for an additional 6 weeks. • Remove cast. Obtain radiographs to evaluate for healing. • Physical therapy is generally not indicated, but some patients may need some therapy for gait training. • Second- and third-generation implants are now available, but there are still limited data on longevity. First-generation implants have a high failure rate. • Both 2 and 3 component implants are available, primarily depending on surgeon preference. • An open anterior approach is used as described in ankle arthrodesis. Major structures at risk include the superficial peroneal nerve and neurovascular bundle. Initial treatment should be nonoperative. NSAIDs, lace-up ankle brace, weight loss if indicated, activity modification (limit uneven surfaces), and corticosteroid injections • Lateral incision is made about 2 cm distal to lateral malleolus, extending to the base fourth metatarsal. Extensor digitorum brevis is reflected to expose subtalar joint. Peroneal tendons are elevated from lateral calcaneous and retracted. • Any remaining cartilage is removed, and the joint is debrided to cancellous bone. • Fusion is performed at 5 degrees valgus. Two cannulated screws are placed from the non–weight-bearing portion of calcaneus toward the anterior margin posterior facet into the talus. Divergent screws have improved compression forces compared with parallel screws or a single screw. Intraoperative radiographs and guidewires are used to ensure appropriate placement of screws (Fig. 8-11). Figure 8-11. Lateral radiograph status post subtalar arthrodesis using two divergent cannulated screws. • The patient may require bone grafting or bone block if bone loss is present from previous trauma/calcaneal fracture. • A posterior splint is applied in the operating room after closure. The patient remains non–weight bearing for 2 weeks. • Weight-bearing ankle AP, mortise, lateral. Assess fracture, alignment, displacement. • Weight bearing foot AP, oblique, lateral. Assess for fracture or malalignment. • Stress radiographs of the ankle should be performed for isolated fibular fractures at the level of the ankle joint. To perform, gravity stress or external rotation and/or abduction stress is applied in a non–weight-bearing mortise view. Medial clear space greater than 4 to 5 mm indicates deltoid ligament injury and ankle instability (Fig. 8-12). • Compare with contralateral ankle (mortise view is best). A 2-mm side-to-side difference in medial clear space indicates instability. • CT scans are helpful to evaluate comminution and subtle displacement. Scan should be performed of bilateral ankles to compare syndesmosis and medial clear space. • MRIs are usually not necessary but can be useful to evaluate the deltoid ligament and help determine ankle stability. • Type A: Transverse fracture at the level of or distal to the tibial plafond • Type B: Spiral, oblique fracture at the level of distal tibiofibular joint and extends proximally. Associated with possible disruption of syndesmosis (Fig. 8-13). • Type C: Fracture proximal to distal tibiofibular joint. Syndesmosis completely disrupted; anterior and posterior tibiofibular ligaments and interosseous membrane ruptured (Fig. 8-14) • Immobilization in cast or walking boot, weight bearing as tolerated. Most fractures heal in 6 weeks. • Consider nonoperative management when medial clear space is less than 4 to 5 mm and less than 2 mm greater than contralateral side on stress and static radiographs. • Immobilization in cast or walking boot for 6 weeks. Weight bearing is progressed as tolerated. • Frequent follow-up with radiographs (weekly for first 2 to 3 weeks). Surgical fixation is recommended if there is a change in stability or alignment. • After 6 weeks of immobilization, transition to brace. Physical therapy may be helpful to regain motion and strength. • Distal fibular fractures—Multiple hardware options are available including locking and nonlocking plates and screws. Locking plates should be used when bone quality is poor or a patient is at high risk for nonunion (diabetes, osteoporosis). • Medial malleolus fractures—Fixation devices include lag, partially threaded, or cannulated screws; Kirshner wires; tension bands; and buttress plate (used only for vertical sheer fractures to prevent proximal migration of fracture fragment). • Dorsal approach: A longitudinal incision is made over the involved web space. The dorsal interosseous fascia is split and retracted. Interosseous muscle is partially detached, metatarsal heads are retracted, and the intermetatarsal ligament is cut. The neuroma is exposed by retracting the digital artery and lumbrical muscle. • Plantar approach: This is generally reserved for revision procedures. A longitudinal incision is made between the metatarsal heads. The plantar fascia is split and retracted to expose the neuroma. • Once neuroma is exposed, it is dissected proximally and cut. The proximal stump retracts into the intrinsic muscles. • Evaluate vascular status after excision to ensure digital artery intact and functioning. • Inspect for presence of corns or calluses, open wounds, swelling, trophic changes, dependent rubor (arterial insufficiency), and bony prominences. • Ulcers often develop at sites of callus formation or as a result of microtrauma. • Increased warmth compared with the contralateral side can indicate Charcot arthropathy, venous insufficiency, or infection. • May be normal in early disease processes • Difficult to differentiate Charcot arthropathy from osteomyelitis • Charcot arthropathy: disorganization of bony structure, bony erosion, intra-articular loose bodies, may have subluxation or dislocation of joints (Fig. 8-16) • Risk Category 0: Normal appearance and sensation, mild to no deformity • Risk Category 1: Normal appearance, insensate, no deformity • Risk Category 2: Insensate foot with deformity, no history of prior ulcer • Risk Category 3: Insensate foot with deformity and history of prior ulcer • Stage 0: Clinical examination findings of erythema and edema. Radiographs are normal. • Stage I: Fragmentation or dissolution phase. Radiographs demonstrate periarticular fragmentation, subluxation, or dislocation of joint. On examination, foot is warm, edematous, and erythematous. • Stage II: Coalescence period, early healing phase. Radiographs show early sclerosis, fusion of bony fragments, and absorption of debris. On examination, there is less erythema and warmth than stage I. • Stage III: Reconstruction phase. Radiographs reveal subchondral sclerosis, osteophytes, and narrow or absent joint spaces. On examination, visual deformity is present and there is no acute inflammation. • Risk Category 0: education, normal footwear, yearly clinical examination • Risk Category 1: education, daily foot self-examination, protective over-the-counter insoles, appropriate footwear, biannual clinical examination • Risk Category 2: education, daily foot self-examination, custom pressure-dissipating accommodative orthoses, inlay depth soft-leather shoes, clinical examination every 4 months • Risk Category 3: education, daily foot self-examination, custom pressure-dissipating orthoses, inlay depth soft-leather shoes, clinical examination every 2 months • Stage I: immobilization using total contact casting, which reduces total load on the foot by one third. Length of immobilization depends on progression of disease/collapse, often 2 to 4 months. • Stage II: ankle-foot orthosis or Charcot restraint orthotic walker (CROW) boot. • Stage III: accommodative shoe and custom insole to decrease pressure on bony prominences • Procedure: Longitudinal incision is made at the border of plantar and dorsal skin. Careful dissection to prominent exostosis and prominent bone is excised using an osteotome or saw. Edges of bone are then smoothed, and precise closure is completed. • Zone 1 (avulsion): Fifth metatarsal tuberosity fracture. Most common type (>90%). Often extends from insertion of peroneal brevis to involve the tarsometarsal joint. • Zone 2 (Jones fracture): Distal to the tuberosity at metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction. Fracture extends to fourth to fifth intermetatarsal joint. Mechanism is adduction or inversion of the forefoot (Fig. 8-18). • Zone 3: Proximal diaphyseal shaft fracture. Rare, less than 3% of fifth MT fractures. Frequently a stress injury and patients may report prodromal pain.

Anatomy

Muscles, nerves, arteries: Figures 8-3, 8-4AB, and 8-5A-C

Physical examination

Inspect for edema, erythema, ecchymosis, deformity, callus formation, ulceration, and hairlessness. On standing examination, note hindfoot alignment. Assess gait pattern.

Inspect for edema, erythema, ecchymosis, deformity, callus formation, ulceration, and hairlessness. On standing examination, note hindfoot alignment. Assess gait pattern.

Palpate to evaluate clinical complaint:

Palpate to evaluate clinical complaint:

Normal range of motion: Table 8-2

Ankle dorsiflexion

10-23 degrees

Ankle plantarflexion

23-48 degrees

Inversion

5-35 degrees

Eversion

5-25 degrees

First metatarsophalangeal dorsiflexion

45-90 degrees

First metatarsophalangeal plantarflexion

10-40 degrees

Differential diagnosis: Table 8-4

Anterior ankle pain

Ankle arthritis, osteochondral dessicans talus

Medial ankle pain

Posterior tibial tendinopathy, medial malleolar injury

Lateral ankle pain

Peroneal tendinopathy, ankle sprain

Posterior ankle pain

Achilles tendinopathy or rupture, os trigonum, posterior impingement

Midfoot

Lisfranc injury, midfoot arthritis

Forefoot

Metatarsal fracture, stress fracture, metatarsalgia

Heel pain

Plantar fasciitis, calcaneal stress fracture, insertional Achilles tendinopathy

Great toe

Hallux rigidus, hallux valgus

Lesser toes

Toe fracture, hammertoe deformity, Morton neuroma

Ankle arthritis

Αnkle arthritis may affect tibiotalar or subtalar joints.

Αnkle arthritis may affect tibiotalar or subtalar joints.

Usually the patient has unilateral ankle pain, stiffness, swelling, ± history of injury. Pain worsens with weight-bearing activity.

Usually the patient has unilateral ankle pain, stiffness, swelling, ± history of injury. Pain worsens with weight-bearing activity.

Post-traumatic most common etiology. Other causes include inflammatory arthritis, neuropathic arthropathy, and primary osteoarthritis (rare).

Post-traumatic most common etiology. Other causes include inflammatory arthritis, neuropathic arthropathy, and primary osteoarthritis (rare).

Imaging

Radiographs: Weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP), mortise, lateral

Radiographs: Weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP), mortise, lateral

Treatment options

First treatment steps include activity modification, weight loss if indicated, lace-up ankle brace, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

First treatment steps include activity modification, weight loss if indicated, lace-up ankle brace, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Intra-articular corticosteroid injection (see ankle injection procedure, page 309). Risks include local skin reaction (depigmentation or subcutaneous fat atrophy) and infection.

Intra-articular corticosteroid injection (see ankle injection procedure, page 309). Risks include local skin reaction (depigmentation or subcutaneous fat atrophy) and infection.

Bracing/shoe modification options are a lace-up ankle brace, an ankle-foot orthotic (AFO), an Arizona brace, and a rocker-bottom sole.

Bracing/shoe modification options are a lace-up ankle brace, an ankle-foot orthotic (AFO), an Arizona brace, and a rocker-bottom sole.

Operative management

Operative indications

Ankle arthrotomy with debridement/loose body removal

Ankle arthrotomy with debridement/loose body removal

Informed consent and counseling

Surgical procedures

Ankle arthrodesis (Fig. 8-8AB)

Ankle arthrodesis (Fig. 8-8AB)

Estimated postoperative course

Total ankle arthroplasty (Fig. 8-9AB)

Total ankle arthroplasty (Fig. 8-9AB)

Estimated postoperative course

Postoperative 2 weeks: non–weight-bearing splint for 1 to 2 weeks. Remove sutures about 2 weeks after surgery and apply a non–weight-bearing cast.

Postoperative 2 weeks: non–weight-bearing splint for 1 to 2 weeks. Remove sutures about 2 weeks after surgery and apply a non–weight-bearing cast.

Postoperative 4 to 6 weeks: transition to weight bearing in a boot. Remove boot multiple times daily for gentle range of motion in plantarflexion and dorsiflexion.

Postoperative 4 to 6 weeks: transition to weight bearing in a boot. Remove boot multiple times daily for gentle range of motion in plantarflexion and dorsiflexion.

Postoperative 3 months: Formal physical therapy may be initiated about 3 months postoperatively if the patient has significant stiffness or weakness.

Postoperative 3 months: Formal physical therapy may be initiated about 3 months postoperatively if the patient has significant stiffness or weakness.

Subtalar arthritis

Imaging

Radiographs: weight-bearing foot AP, lateral, oblique and weight-bearing ankle AP, mortise, lateral

Radiographs: weight-bearing foot AP, lateral, oblique and weight-bearing ankle AP, mortise, lateral

Magnetic resonance imaging/computed tomography (MRI/CT) scan: not necessary for diagnosis. CT will show joint in more detail (osteophytes, subchondral cysts, and loose bodies)

Magnetic resonance imaging/computed tomography (MRI/CT) scan: not necessary for diagnosis. CT will show joint in more detail (osteophytes, subchondral cysts, and loose bodies)

Treatment options

Operative management

Operative indications

Informed consent and counseling

Risks include infection, wound complications, arthritis in surrounding joints, nonunion (reported rates 0.5%), DVT, symptomatic hardware (especially if screw heads are prominent posteriorly). Some patients feel instability on uneven ground. At-risk structures: superficial peroneal and sural nerves, peroneal tendons

Risks include infection, wound complications, arthritis in surrounding joints, nonunion (reported rates 0.5%), DVT, symptomatic hardware (especially if screw heads are prominent posteriorly). Some patients feel instability on uneven ground. At-risk structures: superficial peroneal and sural nerves, peroneal tendons

Surgical procedure

Estimated postoperative course

Postoperative 2 weeks: sutures removed. Non–weight bearing in a boot. Remove boot multiple times daily for ankle motion to prevent stiffness.

Postoperative 2 weeks: sutures removed. Non–weight bearing in a boot. Remove boot multiple times daily for ankle motion to prevent stiffness.

Postoperative 6 weeks: radiograph reviewed. Start weight bearing in boot from weeks 6 to 12.

Postoperative 6 weeks: radiograph reviewed. Start weight bearing in boot from weeks 6 to 12.

Postoperative 3 months: Transition to regular shoes at 12 weeks if fusion is radiographically healed.

Postoperative 3 months: Transition to regular shoes at 12 weeks if fusion is radiographically healed.

Ankle fractures

Physical examination

Edema, ecchymosis, tenderness over fracture site. Medial tenderness without medial malleolus fracture suggests deltoid ligament injury; does not necessarily signify unstable ankle joint

Edema, ecchymosis, tenderness over fracture site. Medial tenderness without medial malleolus fracture suggests deltoid ligament injury; does not necessarily signify unstable ankle joint

Fracture blisters with severe edema and soft tissue trauma

Fracture blisters with severe edema and soft tissue trauma

Visual deformity present if ankle dislocated or severe displacement of fracture

Visual deformity present if ankle dislocated or severe displacement of fracture

Complete neurovascular examination required. If ankle reduction performed, neurovascular examination should be repeated after reduction

Complete neurovascular examination required. If ankle reduction performed, neurovascular examination should be repeated after reduction

Evaluation for syndesmotic injury: palpation of proximal fibula (tenderness suggests syndesmotic injury), calf compression test, external rotation test

Evaluation for syndesmotic injury: palpation of proximal fibula (tenderness suggests syndesmotic injury), calf compression test, external rotation test

Imaging

Classification systems

Danis-Weber classification is based on the location of the fibular fracture and does not address the medial structures.

Danis-Weber classification is based on the location of the fibular fracture and does not address the medial structures.

Lauge-Hansen classification: Fracture types are described by two terms that describe the fracture mechanism. The first term is supination or pronation, and the second term is adduction or external rotation. Additional subtypes exist within each classification.

Lauge-Hansen classification: Fracture types are described by two terms that describe the fracture mechanism. The first term is supination or pronation, and the second term is adduction or external rotation. Additional subtypes exist within each classification.

Initial treatment

Immobilization in sugar tong splint, non–weight bearing, and elevation. Refer to an orthopaedic surgeon to be seen within 7 to 10 days.

Immobilization in sugar tong splint, non–weight bearing, and elevation. Refer to an orthopaedic surgeon to be seen within 7 to 10 days.

Treatment options

Weber A fractures: Nearly all can be treated nonoperatively, even with mild displacement.

Weber A fractures: Nearly all can be treated nonoperatively, even with mild displacement.

Weber B: Isolated Weber B fractures require thorough evaluation to determine stability. If stable, consider nonoperative treatment. Unstable fractures require open reduction, internal fixation (ORIF).

Weber B: Isolated Weber B fractures require thorough evaluation to determine stability. If stable, consider nonoperative treatment. Unstable fractures require open reduction, internal fixation (ORIF).

Weber C: Nonoperative management is not recommended.

Weber C: Nonoperative management is not recommended.

Operative management

Codes

Operative indications

Instability of ankle or syndesmosis, significant fracture displacement

Instability of ankle or syndesmosis, significant fracture displacement

Open fractures require immediate surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy. Staged treatment is often used in open fractures. External fixator is initially placed to stabilize the fracture/joint followed by delayed ORIF once soft tissues allow.

Open fractures require immediate surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy. Staged treatment is often used in open fractures. External fixator is initially placed to stabilize the fracture/joint followed by delayed ORIF once soft tissues allow.

Bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures result in instability of mortise and surgical fixation necessary to stabilize ankle.

Bimalleolar and trimalleolar fractures result in instability of mortise and surgical fixation necessary to stabilize ankle.

Medial malleolar fractures are often associated with injury to the deltoid ligament and most require ORIF.

Medial malleolar fractures are often associated with injury to the deltoid ligament and most require ORIF.

Informed consent and counseling

Risks include wound complications, infection, nonunion, and DVT. The rate of complication is significantly higher in diabetics, nicotine users, and patients with peripheral vascular disease. Post-traumatic arthritis may still occur despite proper stabilization. Major structures at risk are the superficial peroneal nerve (crosses fibula approximately 4 to 5 cm proximal to joint) and saphenous vein (for medial incisions).

Risks include wound complications, infection, nonunion, and DVT. The rate of complication is significantly higher in diabetics, nicotine users, and patients with peripheral vascular disease. Post-traumatic arthritis may still occur despite proper stabilization. Major structures at risk are the superficial peroneal nerve (crosses fibula approximately 4 to 5 cm proximal to joint) and saphenous vein (for medial incisions).

Surgical procedure

Open Reduction, Internal Fixation

Open Reduction, Internal Fixation

Use a lateral approach for fixation of distal fibula, syndesmosis, and possibly posterior malleolus. Longitudinal incision is made directly over the distal fibula. Fibular fracture is reduced and stabilized, restoring proper length and rotation. Intraoperative radiograph is used for reduction, to confirm proper screw length, and to determine stability. After ORIF fibula, a radiograph is taken to evaluate medial clear space. If widening is present after ORIF fibula, a syndesmotic screw is placed (Fig. 8-15).

Use a lateral approach for fixation of distal fibula, syndesmosis, and possibly posterior malleolus. Longitudinal incision is made directly over the distal fibula. Fibular fracture is reduced and stabilized, restoring proper length and rotation. Intraoperative radiograph is used for reduction, to confirm proper screw length, and to determine stability. After ORIF fibula, a radiograph is taken to evaluate medial clear space. If widening is present after ORIF fibula, a syndesmotic screw is placed (Fig. 8-15).

Use a medial approach for fixation of medial malleolar fracture or deltoid ligament repair. A longitudinal incision is made over medial malleolus. The saphenous vein is identified and carefully retracted.

Use a medial approach for fixation of medial malleolar fracture or deltoid ligament repair. A longitudinal incision is made over medial malleolus. The saphenous vein is identified and carefully retracted.

Many fractures require both medial and lateral approaches.

Many fractures require both medial and lateral approaches.

A sugar tong splint is applied before leaving the operating room, and the patient remains non–weight bearing on the affected extremity.

A sugar tong splint is applied before leaving the operating room, and the patient remains non–weight bearing on the affected extremity.

Estimated postoperative course

Postoperative 2 to 3 weeks: Sutures removed. Radiographs are obtained at each postoperative visit until complete healing is noted.

Postoperative 2 to 3 weeks: Sutures removed. Radiographs are obtained at each postoperative visit until complete healing is noted.

In general, the patient should be non–weight bearing with immobilization in a sugar tong splint, cast, or boot for 6 weeks postoperative. Gentle range of motion and partial weight bearing can begin 2 to 4 weeks postoperative when there is good bone quality and stable fixation. Strict immobilization and no weight bearing should be followed for full 6 weeks if there is poor bone quality, ligamentous instability, or less stable fixation.

In general, the patient should be non–weight bearing with immobilization in a sugar tong splint, cast, or boot for 6 weeks postoperative. Gentle range of motion and partial weight bearing can begin 2 to 4 weeks postoperative when there is good bone quality and stable fixation. Strict immobilization and no weight bearing should be followed for full 6 weeks if there is poor bone quality, ligamentous instability, or less stable fixation.

Postoperative 6 weeks: Progress to full weight bearing in boot. Remove boot daily for range of motion.

Postoperative 6 weeks: Progress to full weight bearing in boot. Remove boot daily for range of motion.

Postoperative 8 to 10 weeks: Discontinue boot and progress to shoe with ankle brace.

Postoperative 8 to 10 weeks: Discontinue boot and progress to shoe with ankle brace.

Syndesmotic screw removal should be performed no sooner than 3 to 4 months postoperative. No definitive evidence exists to show a difference in clinical outcome whether a syndesmotic screw is removed or left in place.

Syndesmotic screw removal should be performed no sooner than 3 to 4 months postoperative. No definitive evidence exists to show a difference in clinical outcome whether a syndesmotic screw is removed or left in place.

Plantar fasciitis (PF)

PF is the most common cause of plantar heel pain.

PF is the most common cause of plantar heel pain.

Plantar heel pain at the distal plantar fascia (medial calcaneal tuberosity) may extend into midsubstance plantar fascia.

Plantar heel pain at the distal plantar fascia (medial calcaneal tuberosity) may extend into midsubstance plantar fascia.

Start-up pain is characteristic of PF. Pain is greatest with the first steps in the morning or after prolonged sitting. Symptoms improve or resolve with non–weight bearing.

Start-up pain is characteristic of PF. Pain is greatest with the first steps in the morning or after prolonged sitting. Symptoms improve or resolve with non–weight bearing.

Treatment options

Stretching should be done at minimum three times per day.

Stretching should be done at minimum three times per day.

Dorsiflexion splints worn at night keep the ankle at neutral position to prevent calf and plantar fascia contracture. Most improvement is noted in morning symptoms.

Dorsiflexion splints worn at night keep the ankle at neutral position to prevent calf and plantar fascia contracture. Most improvement is noted in morning symptoms.

Silicone heel cups, arch supports, custom orthotics, or over-the-counter (OTC) orthotics may be helpful. Custom inserts have no proven advantage over prefabricated inserts.

Silicone heel cups, arch supports, custom orthotics, or over-the-counter (OTC) orthotics may be helpful. Custom inserts have no proven advantage over prefabricated inserts.

Physical therapy and iontophoresis may provide symptomatic improvement, but symptoms return within 1 month of discontinuing treatment.

Physical therapy and iontophoresis may provide symptomatic improvement, but symptoms return within 1 month of discontinuing treatment.

Corticosteroid injections (see orthopaedic procedures, plantar fascia injection, page 310) provide focused delivery of anti-inflammatory medication. Risks include fascial rupture and fat pad atrophy. Improvement of symptoms generally lasts less than 3 months.

Corticosteroid injections (see orthopaedic procedures, plantar fascia injection, page 310) provide focused delivery of anti-inflammatory medication. Risks include fascial rupture and fat pad atrophy. Improvement of symptoms generally lasts less than 3 months.

Morton’s (intermetatarsal) neuroma

Physical examination

Tenderness to palpation of intermetatarsal space. Pain is not reproduced with palpation of metatarsal heads or metatarsal-phalangeal (MTP) joints.

Tenderness to palpation of intermetatarsal space. Pain is not reproduced with palpation of metatarsal heads or metatarsal-phalangeal (MTP) joints.

Mulder’s sign: Squeeze forefoot medial to lateral and apply dorsal pressure over affected web space. Positive test is audible or palpable click that causes pain.

Mulder’s sign: Squeeze forefoot medial to lateral and apply dorsal pressure over affected web space. Positive test is audible or palpable click that causes pain.

Edema, erythema, and ecchymosis are not present, and there is ± sensory deficit at affected web space/toes and ± divergence of toes.

Edema, erythema, and ecchymosis are not present, and there is ± sensory deficit at affected web space/toes and ± divergence of toes.

Imaging

Radiographs: Weight-bearing foot AP, lateral, oblique. Neuromas are not visible.

Radiographs: Weight-bearing foot AP, lateral, oblique. Neuromas are not visible.

Ultrasound and MRI: Can be used for atypical presentations, but usually not necessary. Neuroma appears as an ovoid/dumbbell-shaped plantar mass between metatarsal heads.

Ultrasound and MRI: Can be used for atypical presentations, but usually not necessary. Neuroma appears as an ovoid/dumbbell-shaped plantar mass between metatarsal heads.

Ultrasound: A hypoechoic signal is present, but not all neuromas are visible.

Ultrasound: A hypoechoic signal is present, but not all neuromas are visible.

MRI: Best identified on T1 images, low intensity signal. Contrast MRI can differentiate from other masses.

MRI: Best identified on T1 images, low intensity signal. Contrast MRI can differentiate from other masses.

Treatment options

The goals are to alleviate pressure and decrease irritation of the nerve.

The goals are to alleviate pressure and decrease irritation of the nerve.

Shoes with wide toe boxes are best. Avoid high heels.

Shoes with wide toe boxes are best. Avoid high heels.

Metatarsal pads placed proximal to metatarsal heads spread apart the metatarsal heads and decrease pressure on nerve.

Metatarsal pads placed proximal to metatarsal heads spread apart the metatarsal heads and decrease pressure on nerve.

Corticosteroid injections (see orthopaedic procedures, Morton’s neuroma injection, page 311) have variable results. Multiple injections have higher success rates (reported resolution of symptoms 11% to 47%). Risks of injections include atrophy of plantar fat pad and MTP joint subluxation.

Corticosteroid injections (see orthopaedic procedures, Morton’s neuroma injection, page 311) have variable results. Multiple injections have higher success rates (reported resolution of symptoms 11% to 47%). Risks of injections include atrophy of plantar fat pad and MTP joint subluxation.

Surgical procedure

Estimated postoperative course

Dorsal approach: weight bearing as tolerated in hard-soled post-operative shoe. Progress to normal shoe wear and activities as tolerated once incision healed, usually between 2 and 3 weeks postoperative.

Dorsal approach: weight bearing as tolerated in hard-soled post-operative shoe. Progress to normal shoe wear and activities as tolerated once incision healed, usually between 2 and 3 weeks postoperative.

The plantar approach requires greater protection with a splint or cast boot and more limited weight bearing to prevent wound complications. Sutures are removed 2 to 3 weeks postoperative. Progress to normal shoe wear and activities as tolerated once the wound has completely healed. This may be 3 to 4 weeks postoperative.

The plantar approach requires greater protection with a splint or cast boot and more limited weight bearing to prevent wound complications. Sutures are removed 2 to 3 weeks postoperative. Progress to normal shoe wear and activities as tolerated once the wound has completely healed. This may be 3 to 4 weeks postoperative.

Diabetic foot and charcot arthropathy

Diabetics with neuropathy are at high risk for developing ulcers and infections.

Diabetics with neuropathy are at high risk for developing ulcers and infections.

Symptoms of neuropathy are numbness, paresthesias or dysesthesias, slow wound healing, and no pain after injury.

Symptoms of neuropathy are numbness, paresthesias or dysesthesias, slow wound healing, and no pain after injury.

Charcot arthropathy is a destructive disease of bones and joints that occurs in sensory neuropathy. It is noninfectious and progressive. Unilateral involvement occurs at initial presentation.

Charcot arthropathy is a destructive disease of bones and joints that occurs in sensory neuropathy. It is noninfectious and progressive. Unilateral involvement occurs at initial presentation.

Charcot arthropathy can develop in patients with diabetic neuropathy. The average duration of diabetes at onset is 20 to 24 years for type I and 5 to 9 years for type II.

Charcot arthropathy can develop in patients with diabetic neuropathy. The average duration of diabetes at onset is 20 to 24 years for type I and 5 to 9 years for type II.

Risk factors for ulcers are peripheral neuropathy; absent pedal pulses; claudication; trophic skin changes (decreased hair growth, skin discoloration or atrophy); history of ulcer; and hospitalization for foot infection, bony deformity, or peripheral edema.

Risk factors for ulcers are peripheral neuropathy; absent pedal pulses; claudication; trophic skin changes (decreased hair growth, skin discoloration or atrophy); history of ulcer; and hospitalization for foot infection, bony deformity, or peripheral edema.

Physical examination

Visual deformities: Claw-toe deformities are common from loss of intrinsic muscle tone. Rocker-bottom midfoot deformity is often present in Charcot arthropathy of midfoot.

Visual deformities: Claw-toe deformities are common from loss of intrinsic muscle tone. Rocker-bottom midfoot deformity is often present in Charcot arthropathy of midfoot.

Sensory examination: Conduct monofilament testing (Semmes-Weinstein) for loss of protective sensation. The threshold for peripheral neuropathy is 10 grams. Generalized neuropathy with diminished sensation in “stocking” distribution is characteristic of diabetic neuropathy.

Sensory examination: Conduct monofilament testing (Semmes-Weinstein) for loss of protective sensation. The threshold for peripheral neuropathy is 10 grams. Generalized neuropathy with diminished sensation in “stocking” distribution is characteristic of diabetic neuropathy.

Vascular: Decreased or absent pedal pulses indicate peripheral vascular disease. Delayed capillary refill indicates ischemic disease.

Vascular: Decreased or absent pedal pulses indicate peripheral vascular disease. Delayed capillary refill indicates ischemic disease.

Imaging

Radiograph: weight-bearing AP, lateral, oblique of foot and AP, lateral, mortise of ankle

Radiograph: weight-bearing AP, lateral, oblique of foot and AP, lateral, mortise of ankle

Nuclear medicine: Bone scan with indium labeled leukocyte scintigraphy useful to diagnosis osteomyelitis; 93% to 100% sensitivity, 80% specificity

Nuclear medicine: Bone scan with indium labeled leukocyte scintigraphy useful to diagnosis osteomyelitis; 93% to 100% sensitivity, 80% specificity

Classification systems

Multiple classification systems for diabetic foot ulcers, and Charcot arthropathy

Multiple classification systems for diabetic foot ulcers, and Charcot arthropathy

Pinzer “risk factor” system to guide treatment of diabetic patients

Pinzer “risk factor” system to guide treatment of diabetic patients

Classification system of Charcot arthropathy:

Classification system of Charcot arthropathy:

Treatment options

At-risk patients without Charcot arthropathy: based on Pinzur classification

At-risk patients without Charcot arthropathy: based on Pinzur classification

Charcot arthropathy: based on stage

Charcot arthropathy: based on stage

Surgical procedures

Amputation: Level of amputation and surgical techniques vary, depending on disease involvement.

Amputation: Level of amputation and surgical techniques vary, depending on disease involvement.

Arthrodesis: As described in earlier sections of the chapter

Arthrodesis: As described in earlier sections of the chapter

Exostectomy

Estimated postoperative course

Estimated postoperative course

Metatarsal fractures (including jones fracture)

Imaging

Classification system

Fifth metatarsal fractures are classified on the basis of location. Treatment recommendations are based on this classification system.

Fifth metatarsal fractures are classified on the basis of location. Treatment recommendations are based on this classification system.