CHAPTER 14

Anatomical Correlation of Common Patterns of Spasticity

Mayank Pathak and Daniel Truong

Spasticity and upper motor neuron syndrome (UMNS) produce abnormal involuntary postures of the affected body parts. The particular posture assumed depends on the size, strength, and relative degree of tone among the various muscles that act across the joint in question. The summation of the various force vectors exerted by these muscles—a complex interaction of agonists, antagonists, and supplementary muscles—along with the viscoelasticity of the muscles involved determines the particular posture assumed at any joint or set of joints. Thus, it is important to understand not only the structure of a particular joint and the different directions in which it can move but also the location and relative strengths of muscles that cross it. Knowledge of the origins and insertions of these muscles will help the practitioner to understand the kinesiology and directions of their pull and thus determine which ones are most active in a particular spastic patient. To facilitate a better understanding of this clinical phenomenon, this chapter discusses these anatomical considerations for major joints of the upper and lower limbs.

THE SHOULDER

Anatomy

Joint. To facilitate its function, the shoulder has the most degrees of freedom of movement of any joint in the body. The primary shoulder joint, that is, the glenohumeral articulation, is a multiaxial joint, with the spheroid head of the humerus being held in the shallow concavity of the glenoid fossa of the scapula (1). This nominal ball-and-socket arrangement would fall apart if not strapped together by the muscles and tendons that run across it. As a result of this fact, numerous postural abnormalities may be encountered as a result of UMNS. The actions of various shoulder muscles are complex and may be different depending on the starting position, which part of a particular muscle is exerting the most force, and whether their points of origin or insertion are fixed at the start of the motion. The following discussion on the major shoulder muscles is arranged according to their major vector of action among patients with spasticity.

Abduction. The deltoid originates along the acromion and adjacent clavicle, running across the shoulder joint to insert on the shaft of the humerus (Figures 14.1 and 14.9). Its action is to abduct the humerus (2). It is generally overpowered by adductors in spasticity.

External rotation. Underneath the deltoid lies a group of four muscles that make up the rotator cuff. Three of these comprise the external rotators: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor, all of which originate on the posterior aspect of the scapula and insert on the posterior surface of the proximal part of the humerus, at and below the greater tubercle (Figure 14.1). Their action is to externally rotate the humerus, with the supraspinatus also contributing to abduction (3).

Internal rotation. The fourth rotator cuff muscle, that is, the subscapularis, originates on the anterior surface of the scapula, extending forward to insert on the lesser tubercle on the anterior surface of the humerus, thereby preventing anterior subluxation of the humeral head; its action is to internally rotate the humerus while thrusting the scapula forward (4).

The most powerful internal rotator is the pectoralis major, which has a clavicular head originating from the medial half of the clavicle on its anterior side and a sternocostal head originating from the sternum, the costal cartilage of ribs 1 to 6, rib 7, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique (Figure 14.2). These fibers all converge to insert on the anterolateral humerus. The principal action of the pectoralis major is to adduct and medially rotate the humerus, and it also acts as a flexor of the glenohumeral joint for the first 60° (6,7).

FIGURE 14.1 Deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and teres major.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

The teres major originates on the posterior surface of the scapula near the inferior angle, inserting medial to the anterior midline bicipital ridge of the humerus (Figures 14.1 and 14.3). It is involved in internal rotation and extension of the humerus (6).

Elevation. The next two muscles to be discussed are shoulder elevators. The levator scapulae originates from the transverse processes of C1 to C4, inserting on the upper medial border of the scapula (Figure 14.4), its actions being to elevate the scapula and rotate the top outward. The trapezius originates from the occiput, nuchal ligament, and spinous processes of the cervical and thoracic vertebrae (Figure 14.4). Its upper fibers insert on the lateral clavicle and acromion, and its middle and lower fibers insert along the scapular spine. The upper fibers elevate the scapula and the entire shoulder joint. Activation of the middle and lower fibers can adduct and depress the scapula (8).

FIGURE 14.2 Pectoralis major and pectoralis minor.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

FIGURE 14.3 Latissimus dorsi and teres major.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Other muscles. The latissimus dorsi originates along a wide stretch of medial back structures from the sacrum to the midthoracic vertebrae, inserting medial to the anterior midline of the proximal humerus (Figure 14.3), its main actions being adduction, internal rotation, and extension (9,10).

FIGURE 14.4 Semispinalis capitis, splenius capitis, levator scapulae, and trapezius.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

The coracobrachialis originates on the coracoid process and inserts on the medial surface of the humeral shaft, flexing and adducting the humerus (11). The pectoralis minor originates on ribs 3 to 5 and runs diagonally cephalad and laterally to insert on the coracoid process of the scapula (Figure 14.2). With the ribs fixed, it pulls the scapula downward and forward, moving the shoulder joint anteriorly.

Spastic Postures

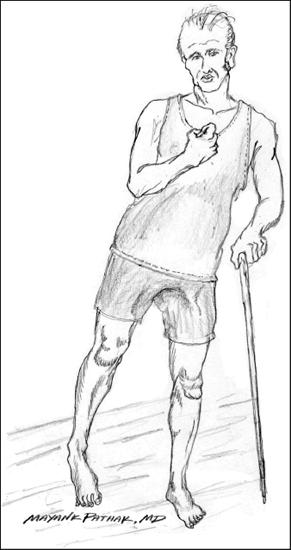

Shoulder adduction and internal rotation. Muscles that adduct and internally rotate the humerus at the glenohumeral joint are the strongest; thus, the adducted and internally rotated posture is the most commonly encountered among spastic patients (Figure 14.5). Activities that are impaired by this posture and that can be ameliorated by the application of botulinum toxin include donning and doffing of clothing, caregiver-assisted mobility and transfers, and hygienic care of the axilla (12). The principal muscles involved in this posture include the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis, any or all of which may be targeted for chemodenervation.

Shoulder hyperextension. Hyperextension is a less common pattern of spastic posture but can occur if the subscapularis and pectoralis muscles are not strongly contractile. This allows the latissimus dorsi and teres major, along with the posterior deltoid and long head of the triceps, to pull the humerus in a posterior direction. With spasticity in the shoulder extensor muscles, active shoulder flexion may be slowed.

FIGURE 14.5 Right-sided spastic hemiplegia.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Shoulder subluxation. After acute central nervous system injury, there is an initial period of flaccidity before the onset of spasticity. During this flaccid phase, sufficient laxity may occur in the rotator cuff and other shoulder strap muscles to allow inferior and/or anterior subluxation of the glenohumeral joint, especially when traction is placed on the paretic limb by caregivers attempting to move the patient (13). This subluxation may become a chronic problem, failing to resolve after the onset of spasticity, and can lead to long-term pain and increase in disability (14,15). In treating shoulder joint spasticity with botulinum toxin, it is important to assess for the presence of subluxation and to avoid exacerbating the problem by chemodenervation of rotator cuff muscles or by excessive dosing of other muscles crossing the humerus. These can include the deltoid and the pectoralis major and minor.

THE ELBOW

Joint anatomy. The elbow is capable of four types of movement: flexion, extension, pronation, and supination. Flexion/extension movements occur at the humeroulnar joint, a hinge-like complex comprised of the rounded trochlea of the distal humerus resting in the concave trochlear notch of the proximal ulna. Pronation and supination occur at the humeroradial joint, a biaxial joint that can rotate along the long axis of the radius and is able to move in a transverse axis during flexion/extension (16). Any combination of these directions of movement can be involved in spastic posturing.

Flexion and supination. Because the flexors and supinators are more powerful, they generally predominate in spasticity; thus, the flexed elbow with the forearm supinated is most frequently encountered among patients (Figure 14.5).

The principal muscles involved in elbow flexion and supination are the biceps, brachialis, brachioradialis, and pronator teres (discussed under pronation). The elbow flexors are strongest in work in different positions. The biceps is strongest in supination, whereas the brachialis is most involved in pronation, and the brachioradialis is strongest in the neutral position. The biceps has two heads, each originating on different parts of the scapula: a short head originating on the coracoid process and a long head originating on the supraglenoid tubercle (Figure 14.6). The biceps inserts onto the radial tuberosity and also forms the bicipital aponeurosis, which inserts into the fascia of the medial forearm (Figure 14.7). The biceps thus produces both flexion and strong supination of the forearm at the elbow joint (17).

The brachialis originates over a large area of the distal half of the anterior humerus and inserts onto the coronoid process and tuberosity of the proximal ulna (Figure 14.6). It is a pure flexor of the elbow; not inserting on the radius, it makes no contribution to the rotation of the radius and therefore does not pronate or supinate the forearm (18). The third elbow flexor, that is, brachioradialis, originates on the distal humerus and inserts distally on the styloid process of the radius (Figure 14.8).

FIGURE 14.6 Biceps and brachialis.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Extension. Extension is a less common spastic posture at this joint and is produced by two muscles, the triceps brachii and anconeus. The triceps, forming the bulk of the posterior upper arm, has, as its name indicates, three heads (Figure 14.9). Two of these, the medial and lateral heads, originate along the posterior humerus, whereas the third, the long head, originates on the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula. The triceps crosses the elbow joint to insert on the olecranon process of the ulna. The second elbow extensor muscle is the anconeus. Originating on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, it inserts distal to the joint on the olecranon and adjacent part of the proximal ulna (19). Its belly can be palpated over the lateral part of the olecranon, and it plays a minor role in extension movements.

Pronation. Pronator teres has a humeral head originating on the medial epicondyle of the humerus and contributing to elbow flexion and an ulnar head originating on the coronoid process of the proximal ulna and producing pronation of the forearm (Figure 14.7). Pronation also occurs at the wrist, being produced by the pronator quadratus, which originates on the anteromedial surface of the distal ulna and inserts on the anterior surface of the radius (20).

FIGURE 14.7 Flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, pronator teres, and pronator quadratus.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

FIGURE 14.8 Flexor digitorum superficialis, FCU, brachioradialis, FCR, and palmaris longus.

FCR, flexor carpi radialis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris.

Source: Reprinted with permission from Ref. (5). Truong D, Dressler D, Hallett M, eds. Manual of Botulinum Toxin Therapy. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

THE WRIST

Joint anatomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree