Orthotics and Prosthetics in Rehabilitation

Multidisciplinary Approach

Caroline C. Nielsen and Milagros Jorge

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

Allied health professionals work in health care settings to meet the physical rehabilitation needs of diverse patient populations. Today’s health care environment strives to be patient-centered and advocates the use of best practice models that maximize patient outcomes while containing costs. The use of evidence-based treatment approaches, clinical practice guidelines, and standardized outcome measures provides a foundation for evaluating and determining efficacy in health care across disciplines. The World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF)1 provides a disablement framework that enables health professionals to maximize patient/client participation and function while minimizing disability. In this complex environment, current and evolving patterns of health care delivery focus on a team approach to the total care of the patient.

For a health care team to function effectively, each member must develop a positive attitude toward interdisciplinary collaboration. The collaborating health professional must understand the functional roles of each health care discipline within the team and must respect and value each discipline’s input in the decision-making process of the health team.2,3 Rehabilitation, particularly when related to orthotics and prosthetics, lends itself well to interdisciplinary teams because the total care of patients with complex disorders requires a wide range of knowledge and skills.4 The physician, prosthetist, orthotist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, nurse, and social worker are important participants in the rehabilitation team. Understanding the roles and professional responsibilities of each of these disciplines maximizes the ability of the rehabilitation team members to function effectively to provide comprehensive care for the patient.

According to disability data from the American Community Survey 2003, 11.5% of civilian household populations aged 16 to 64 years reported having a disability.5 Approximately 1.7 million people in the United States live with limb loss.6 The U.S. military engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in limb loss for more than 1000 soldiers.7 The obesity epidemic in the United States has given rise to more people with diabetes who are at risk for dysvascular disease, such as peripheral arterial disease (PAD), which often results in musculoskeletal and neuromuscular impairments to the lower extremities. Ischemic disease can cause peripheral neuropathy, loss of sensation, poor skin care and wound formation, trophic ulceration, osteomyelitis, and gangrene, which can result in the need for amputation. Eight million Americans have PAD.8

Persons coping with illness, injury, disease, impairments, and disability often require special orthotic and prosthetic devices to help with mobility, stability, pain relief, and skin and joint protection. Appropriate prescription, fabrication, instruction, and application of the orthotic and prosthetic devices help persons to engage in activities of daily living as independently as possible. Prosthetists and orthotists are allied health professionals who custom-fabricate and fit prostheses and orthoses. Along with other health care professionals, including nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists, posthestists and orthotists are integral members of the rehabilitation teams responsible for returning patients to productive and meaningful lives. Definitions of disability continue to evolve. Current definitions consider social, behavioral, and environmental factors that affect the person’s ability to function in society. These definitions have considerably broadened the original pathology model in which disability was a function of a particular disease or group of diseases.9 The current, more inclusive model requires expertise from many sectors in rehabilitative care. This chapter discusses the developmental history of the art and science of orthotics, prosthetics, and physical therapy as professions dedicated to rehabilitating persons with injury and disability.

Prosthetists and orthotists

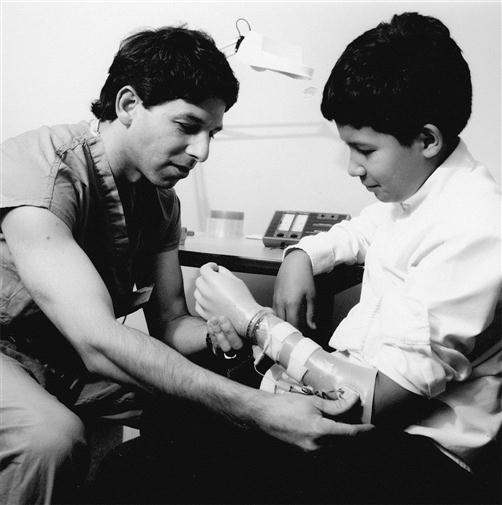

Prosthetists provide care to patients with partial or total absence of limbs by designing, fabricating, and fitting prostheses or artificial limbs. The prosthetist creates the design to fit the individual’s particular functional and cosmetic needs; selects the appropriate materials and components; makes all necessary casts, measurements, and modifications (including static and dynamic alignment); evaluates the fit and function of the prosthesis on the patient; and teaches the patient how to care for the prosthesis (Figure 1-1).

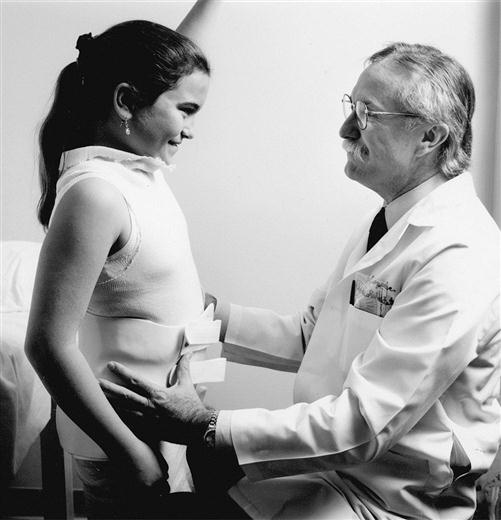

Orthotists provide care to patients with neuromuscular and musculoskeletal impairments that contribute to functional limitation and disability by designing, fabricating, and fitting orthoses, or custom-made braces. The orthotist is responsible for evaluating the patient’s functional and cosmetic needs, designing the orthosis, and selecting appropriate components; fabricating, fitting, and aligning the orthosis; and educating the patient on appropriate use (Figure 1-2).

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2009, there were 5470 certified prosthetists and orthotists practicing in the United States.10 An individual who enters the fields of prosthetics and orthotics today must complete advanced education (beyond an undergraduate degree) and residency programs before becoming eligible for certification. Registered assistants and technicians in orthotics or prosthetics assist the certified practitioner with patient care and fabrication of orthotic and prosthetic devices.

History

The emergence of orthotics and prosthetics as health professions has followed a course similar to the profession of physical therapy. Development of all three professions is closely related to three significant events in world history: World War I, World War II, and the onset and spread of polio in the 1950s. Unfortunately, it has taken war and disease to provide the major impetus for research and development in these key areas of rehabilitation.

Although the profession of physical therapy has its roots in the early history of medicine, World War I was a major impetus to its development. During the war, female “physical educators” volunteered in physicians’ offices and Army hospitals to instruct patients in corrective exercises. After the war ended, a group of these “reconstruction aides” joined together to form the American Women’s Physical Therapy Association. In 1922, the association changed its name to the American Physical Therapy Association, opened membership to men, and aligned itself closely with the medical profession.11

Until World War II, the practice of prosthetics depended on the skills of individual craftsmen. The roots of prosthetics can be traced to early blacksmiths, armor makers, other skilled artisans, and even the individuals with amputations, who fashioned makeshift replacement limbs from materials at hand. During the Civil War, more than 30,000 amputations were performed on Union soldiers injured in battle; at least as many occurred among injured Confederate troops. At that time, most prostheses consisted of carved or milled wooden sockets and feet. Many were procured by mail order from companies in New York or other manufacturing centers at a cost of $75 to $100 each.12 Before World War II, prosthetic practice required much hands-on work and craftsman’s skill. D. A. McKeever, a prosthetist who practiced in the 1930s, described the process: “You went to [the person with an amputation’s] house, took measurements and then carved a block of wood, covered it with rawhide and glue, and sanded it.” During his training, McKeever spent three years in a shop carving wood: “You pulled out the inside, shaped the outside, and sanded it with a sandbelt.”13

The development of the profession of orthotics mirrors the field of prosthetics. Early “bracemakers” were also artisans such as blacksmiths, armor makers, and patients who used many of the same materials as the prosthetist: metal, leather, and wood. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, splints and braces were also mass produced and sold through catalogs. These bracemakers were also frequently known as “bonesetters” until surgery replaced manipulation and bracing in the practice of orthopedics. “Bracemaker” then became a profession with a particular role distinct from that of the physician.14

World War II and the period following were times of significant growth for the professions of physical therapy, prosthetics, and orthotics. During the war, many more physical therapists were needed to treat the wounded and rehabilitate those who were left with functional impairments and disabilities. The Army became the major resource for physical therapy training programs, and the number of physical therapists serving in the armed services increased more than sixfold.15 The number of soldiers who required braces or artificial limbs during and after the war increased the demand for prosthetists and orthotists as well.

After World War II, a coordinated program for persons with amputations was developed. In 1945, a conference of surgeons, prosthetists, and scientists organized by the National Academy of Sciences revealed that little scientific effort had been devoted to the development of artificial limbs. A “crash” research program was initiated, funded by the Office of Scientific Research and Development and continued by the Veterans Administration. A direct result of this effort was the development of the patellar tendon-bearing prosthesis for individuals with transtibial (below-knee) amputation and the quadrilateral socket design for those with transfemoral (above-knee) amputation. This program also included educating prosthetists, physicians, and physical therapists in the skills of fitting and training of patients with these new prosthetic designs.16

The needs of soldiers injured in the military conflicts in Korea and Vietnam ensured continuing research, further refinements, and development of new materials. The development of myoelectrically controlled upper extremity prostheses and the advent of modular endoskeletal lower extremity prostheses occurred in the post–Vietnam conflict era. In 2008, the U.S. Department of Defense reported military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan (Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraq Freedom) have resulted in loss of limb for 1214 service men and women.17 Veterans Health Administration Research Development is committed to exploring the use of new technology such as robotics, tissue engineering, and nanotechnology to design and build lighter, more functional prostheses that look, feel, and respond more like real arms and legs.18

The current term, orthotics, emerged in the late 1940s and was officially adopted by American orthotists and prosthetists when the American Orthotic and Prosthetic Association was formed to replace its professional predecessor, the Artificial Limb Manufacturers’ Association. Orthosis is a more inclusive term than brace and reflects the development of devices and materials for dynamic control in addition to stabilization of the body. In 1948, the American Board for Certification in Orthotics and Prosthetics was formed to establish and promote high professional standards.

Although the polio epidemic of the 1950s played a role in the further development of the physical therapy profession, this epidemic had the greatest effect on the development of orthotics. By 1970, many new techniques and materials, some adapted from industrial techniques, were being used to assist patients in coping with the effects of polio and other neuromuscular disorders. The scope of practice in the field of orthotics is extensive, including working with children with muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, and spina bifida; patients of all ages recovering from severe burns or fractures; adolescents with scoliosis; athletes recovering from surgery or injury; and older adults with diabetes, cerebrovascular accident, severe arthritis, and other disabling conditions.

Like physical therapists, orthotists and prosthetists practice in a variety of settings. The most common setting is the private office, where the professional offers services to a patient on referral from the patient’s physician. Many large institutions, such as hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and research institutes, have departments of orthotics and prosthetics with on-site staff to provide services to patients. The prosthetist or orthotist may also be a supplier or fabrication manager in a central production laboratory. In addition, some orthotists and prosthetists serve as full-time faculty in one of the 10 programs that are available for orthotic and prosthetic entry-level training or in one of the programs available at the master of science level.19 Others serve as clinical educators in a variety of facilities for the year-long residency program required before the certification examination.

Prosthetic and orthotic professional roles and responsibilities

With rapid advances in technology and health care, the roles of the prosthetist and orthotist have expanded from a technological focus to a more inclusive focus on being a member of the rehabilitation team. Patient examination, evaluation, education, and treatment are now significant responsibilities of practitioners. Most technical tasks are completed by technicians who work in the office or in the laboratory, or at an increasing number of central fabrication facilities. The advent and availability of modifiable prefabrication systems have reduced the amount of time that the practitioner spends crafting new prostheses and orthoses.

Current educational requirements reflect these changes in orthotic and prosthetic practice. Entry into professional training programs requires completion of a bachelor’s degree from an accredited college or university, with a strong emphasis on prerequisite courses in the sciences. Professional education in orthotics or prosthetics requires an additional academic year for each discipline. Along with the necessary technical courses, students study research methodology, kinesiology and biomechanics, musculoskeletal and neuromuscular pathology, communication and education, and current health care issues. Orthotics and prosthetics programs are most often based within academic health centers or in colleges or universities with hospital affiliations. After completion of the academic program, a year-long residency begins, during which new clinicians gain expertise in the acute, rehabilitative, and long-term phases of pediatrics and adult care. On completion of the educational and experiential requirements, the student is eligible to sit for the certification examinations. In order to address the rehabilitation needs of individuals who will benefit from the art and science of the fields of prosthetics and orthotics, physical therapists, orthotists, prosthetists, and other members of the health care team must have discreet knowledge and skills in the management of persons with a variety of health conditions across the lifespan. Working as a rehabilitation team, physicians, nurses, prosthetists, orthotists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, patients, and family members seek to maximize function and alleviate disease, injury, impairments, and disability.

Disablement frameworks

Historically, disability was described using a theoretical medical model of disease and pathology. Over time, various conceptual frameworks have been developed to organize information about the process and effects of disability.20 Disablement frameworks in the past have been used to understand the relationship of disease and pathology to human function and disability.20–23 The need to understand the impact that acute injury or illness and chronic health conditions have on the functioning of specific body systems, human performance in general, and on the typical activities of daily living from both the individual and a societal perspective has been central to the development of the disablement models. The biomedical model of pathology and dysfunction provided the conceptual framework for understanding human function, disability, and handicap as a consequence of pathological and disease processes.

The Nagi model was among the first to challenge the appropriateness of the traditional biomedical model of disability.21 Nagi developed a model that looked at the individual in relationship to the pathology, functional limitations, and the role that the environment and society or the social environment played. The four major elements of Nagi’s theoretical formulation included active pathology (interference with normal processes at the level of the cell), impairment (anatomical, physiological, mental, or emotional abnormalities or loss at the level of body systems), functional limitation (limitation in performance at the level of the individual), and disability. Nagi defined disability as “an expression of physical or mental limitation in a social context.”21 The Nagi model was the first theoretical construct on disability that considered the interaction between the individual and the environment from a sociological perspective rather than a purely biomedical perspective. Despite the innovation of the Nagi model in the 1960s, the biomedical model of disability persisted.

In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (ICIDH) to provide a standardized means of classifying the consequences of disease and injury for the collection of data and the development of social policy.24 This document provided a framework for organizing information about the consequences of disease. However, it focused solely on the effects of pathological processes on the individual’s activity level. Disability was viewed as a result of an impairment and considered a lack of ability to perform an activity in the normal manner. In 1993, the WHO began a revision of ICIDH disablement framework that gave rise to the concept that a person’s handicap was less related to the health condition that created a disadvantage for completing the necessary life roles but rather to the level of participation that the person with the health condition was able to engage in within the environment. The concept of being handicapped was changed to be seen as a consequence of the level of participation for the person and the interaction within an environment.

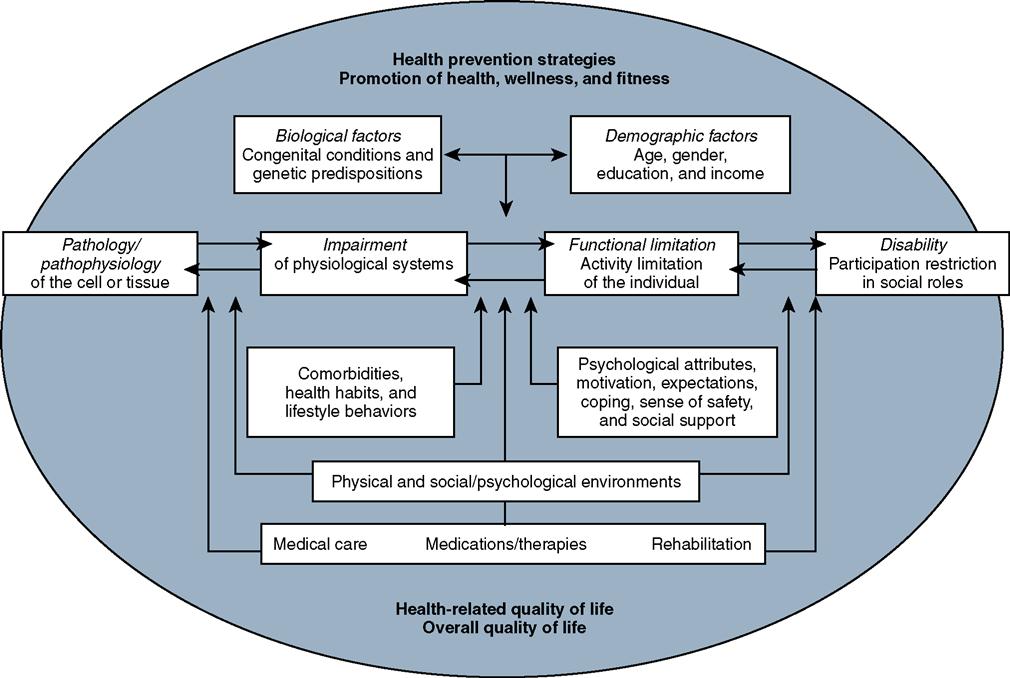

The Institute of Medicine enlarged Nagi’s original concept in 1991 to include the individual’s social and physical environment (Figure 1-3). This revised model describes the environment as “including the natural environment, the built environment, the culture, the economic system, the political system, and psychological factors.” In this model, disability is not viewed as a pathosis residing in a person but instead is a function of the interaction of the person with the environment.25

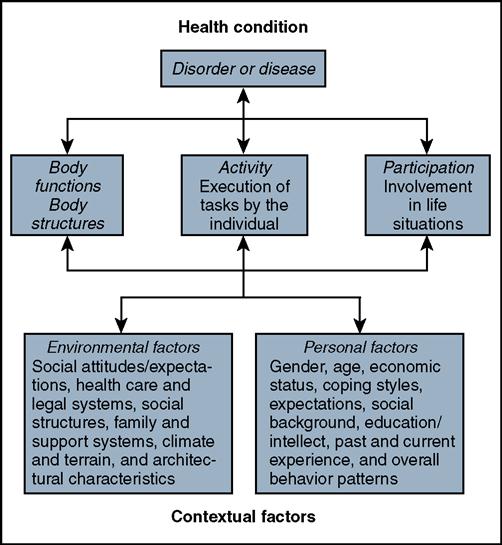

In 2001, ICIDH was revised to ICIDH-2 and renamed “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health” and is commonly referred to as ICF.26 The ICF disablement framework includes individual function at the level of body/body part, whole person, and whole person within a social context. The model helps in the description of changes in body function and structure, what people with particular health conditions can do in standard environments (their level of capacity), as well as what they actually do in their usual environments (their level of performance). One of the major innovations of the ICF model is the presence of an environmental factor classification that considers the role of environmental barriers and facilitators in the performance of tasks of daily living. Disability becomes an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. The ICF model emphasizes health and functioning rather than disability. The ICF model provides a radical departure from emphasizing a person’s disability to focusing on the level of health and facilitating an individual’s participation to whatever extent is possible within that level of health. In the ICF, disability and functioning are viewed as outcomes of interactions between health conditions (diseases, disorders, and injuries) and contextual factors (Figure 1-4).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree