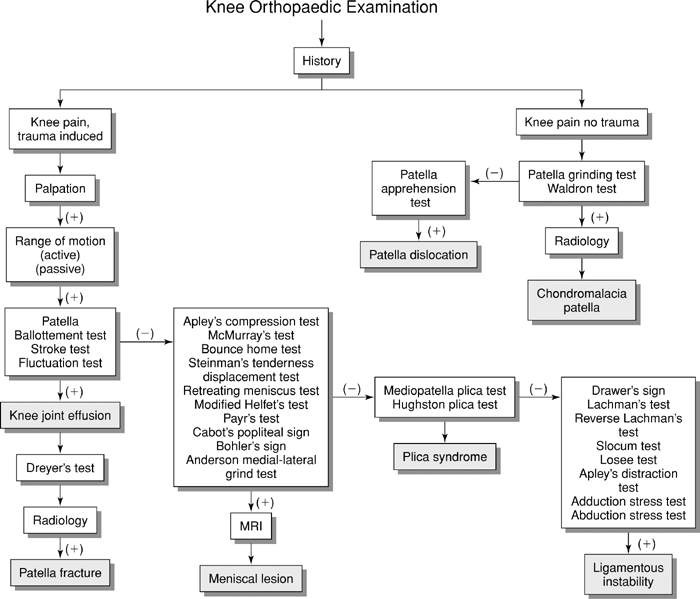

Knee Orthopaedic Tests

Palpation

Anterior Aspect

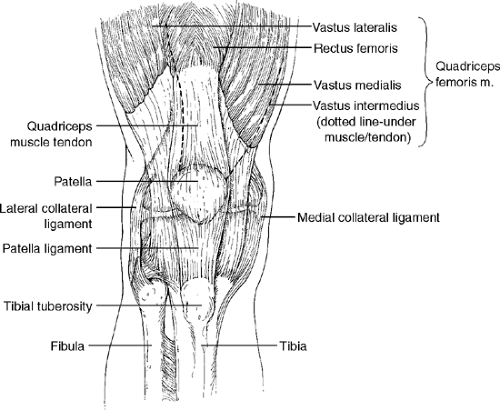

Patella, Quadriceps Femoris Tendon, and Patella Ligament

Descriptive Anatomy

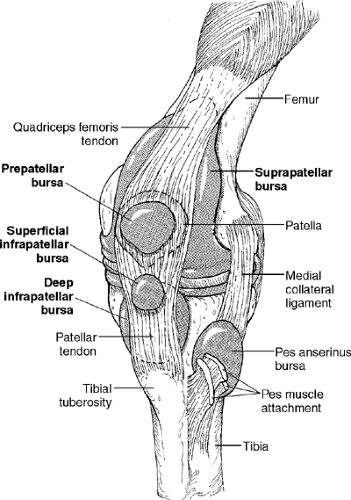

The suprapatellar tendon anchors the patella to the anterior aspect of the knee superiorly. This tendon is an extension of the quadriceps muscle and it continues inferiorly as the patellar ligament (Fig. 14-1). The patellar ligament is thick, strong, and continuous with the fibrous capsule of the knee joint, and it attaches to the tibial tuberosity. These structures, which are superficial and easily palpable, function as a lever to extend the leg when the quadriceps muscle contracts.

Procedure

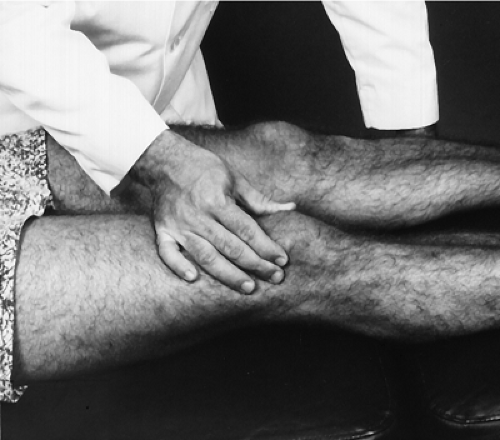

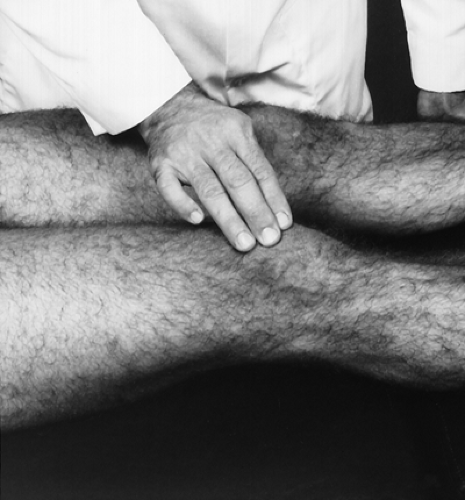

With the patient supine and the knee extended, palpate the patella and its margins (Fig. 14-2). Note any tenderness, inflammation, temperature differences, and/or roughness. Tenderness and pain from direct trauma may indicate periosteal contusion or fracture of the patella. Swelling and an increase in temperature suggest prepatellar bursitis. Roughness at the margins of the patella may indicate chondromalacia patellae, or degeneration of the undersurface of the patella.

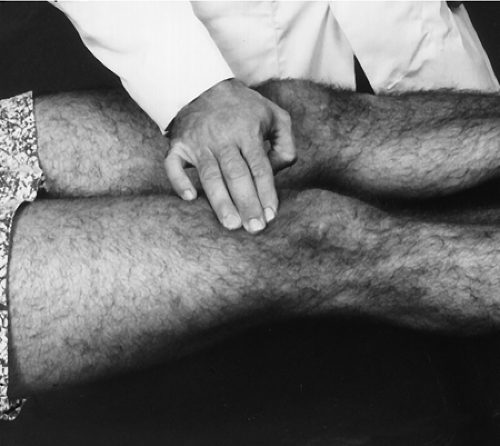

Next, palpate the quadriceps femoris tendon (Fig. 14-3). Tenderness may indicate tendinitis caused by overuse or strain resulting from overstress. Continue palpation inferior to the patella which is the patellar ligament. Palpate from the apex of the patella, which is the inferior margin, down to the tibial tubercle, which is the attachment of the patellar ligament (Fig. 14-4). Note any pain, tenderness, swelling, or temperature differences. Any of these findings may indicate ligament sprain. If symptoms are local to the tibial tuberosity, suspect Osgood-Schlatter disease, an enlargement of the tibial tuberosity, in the adolescent; it is common in young adults.

Descriptive Anatomy

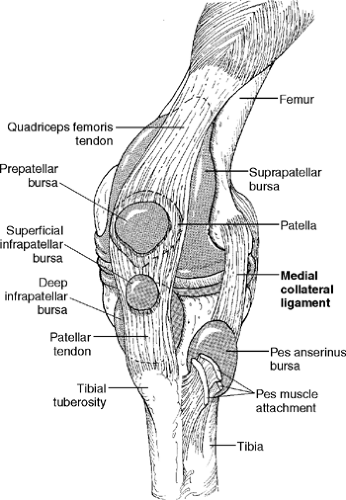

The clinically important bursae in the anterior aspect of the knee are the suprapatellar bursa, prepatellar bursa, superficial infrapatellar bursa, and deep infrapatellar bursa (Fig. 14-5). The suprapatellar bursa, an extension of the synovial capsule, lies between the femur and the quadriceps femoris tendons. It allows for movement of the quadriceps tendon over the distal end of the femur. The prepatellar bursa is superficial to the patella between the skin and anterior surface of the patella. It allows movement of the skin over the underlying patella. The superficial infrapatellar bursa is between the tibial tuberosity and the skin. It allows for movement of the skin over the tibial tuberosity. The deep infrapatellar bursa lies between the patellar ligament and the tibia. This allows for movement of the patellar ligament over the tibia.

Procedure

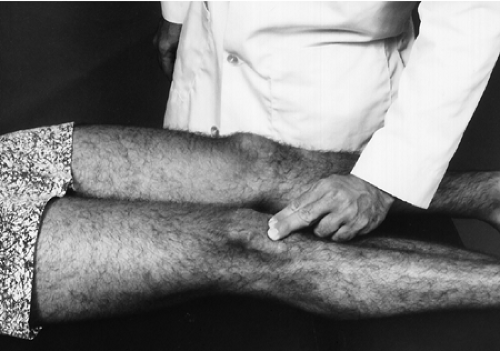

Palpate the suprapatellar bursa above the patella (Fig. 14-6). Note any thickening, tenderness, or temperature differences. These signs may indicate bursitis in the suprapatellar bursa or pathology in the quadriceps femoris tendon. Next, palpate the prepatellar bursa, which is superficial to the patella (Fig. 14-7). Note any thickening, swelling, tenderness, or temperature differences. These signs may indicate prepatellar bursitis (housemaid’s knee). Palpate the superficial and deep infrapatellar bursa (Fig. 14-8). Note any thickening, swelling, tenderness, or temperature differences. Any of these may indicate infrapatellar bursitis or patellar ligament pathology.

Descriptive Anatomy

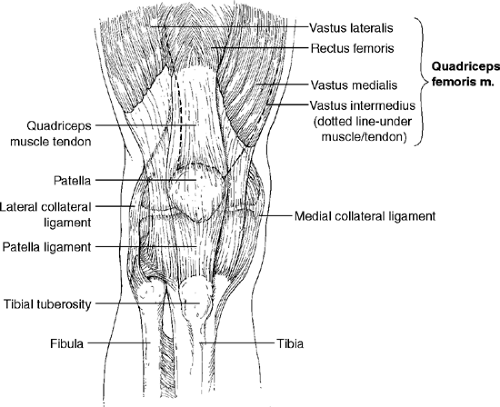

The quadriceps femoris consists of four muscles: rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius (Fig. 14-9). The primary action of these muscles is to extend the leg at the knee. They all unite to form the quadriceps tendon, which inserts into the patella.

Procedure

Palpate the entire length of the quadriceps muscle, noting any swelling, tenderness, temperature differences, or masses (Fig. 14-10). Tenderness and/or swelling may indicate muscle strain or hematoma. Point tenderness at the upper aspect of the muscle may indicate active trigger points and may refer pain to the knee. A hard mass secondary to trauma may indicate myositis ossificans, which is an ossification of muscle tissue.

Medial Aspect

Descriptive Anatomy

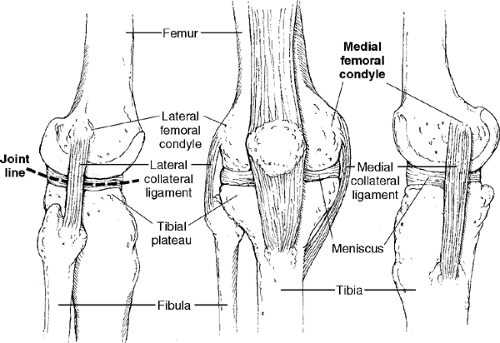

The medial femoral condyle is a bony prominence on the medial aspect of the distal femur, which is the attachment of the medial collateral ligament. The medial tibial plateau and joint line are important palpable landmarks of the medial aspect of the knee. The medial aspect of the meniscus is in the joint line, and the coronary ligament attaches the meniscus to the tibial plateau (Fig. 14-11).

Procedure

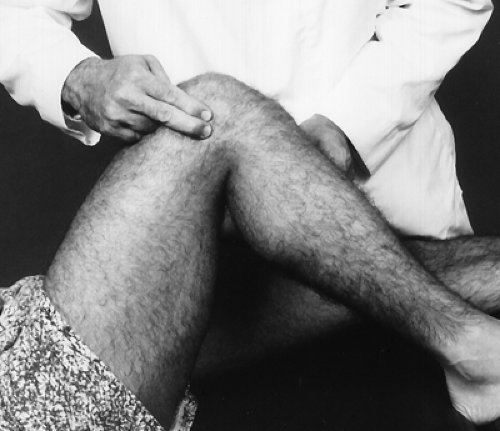

With the knee in 90° of flexion, palpate the medial femoral condyle with your index and middle fingers (Fig. 14-12). Note any tenderness or pain. These signs may indicate a sprain, avulsion, or calcification (Pellegrini-Stieda disease) of the medial collateral ligament. Next, palpate the tibial plateau and medial joint line. Note any tenderness or pain. These signs may indicate a tear of the medial meniscus or sprain of the coronary ligament.

Descriptive Anatomy

The medial collateral, or tibial collateral, ligament is a strong, broad, flat band that extends from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial condyle and upper medial aspect of the tibia (Fig. 14-13). It contributes to the medial stability of the knee. Its fibers are attached to the medial meniscus and the fibrous capsule of the knee.

Procedure

With the patient supine and the leg extended, palpate the medial collateral ligament from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial condyle of the tibia with your index and middle fingers (Fig. 14-14). Note any pain, tenderness, or defect in the ligament. Pain and tenderness may indicate a sprain of the ligament. A deficit secondary to trauma may indicate a tear of the ligament, which is usually associated with capsular and meniscal damage. A defect at either the medial femoral epicondyle or the medial tibial condyle suggests an avulsion fracture secondary to trauma.

Lateral Aspect

Descriptive Anatomy

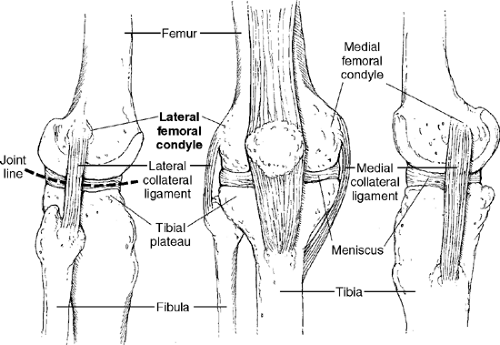

The lateral femoral condyle is a bony prominence on the lateral aspect of the distal femur, which is the attachment of the lateral collateral ligament and iliotibial band. This structure is important for the lateral stability of the knee. The lateral joint line is an important palpable landmark of the lateral aspect of the knee. The lateral aspect of the meniscus and the coronary ligament, which attaches the meniscus to the tibia, are in the joint line (Fig. 14-15).

Procedure

With the knee in 90° of flexion, palpate the lateral femoral condyle with your index and middle fingers (Fig. 14-16). Note any tenderness or pain. These signs may indicate sprain, avulsion, or calcification of the lateral collateral ligament. Next, palpate the lateral joint line. Note any tenderness or pain. These signs may indicate a tear of the lateral meniscus or strain of the coronary ligament.

Descriptive Anatomy

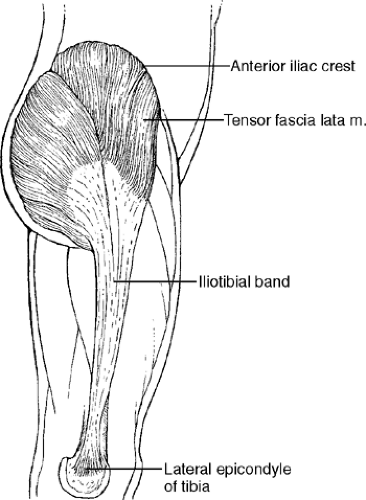

The lateral collateral ligament is a round cord that extends from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula (Fig. 14-15). This structure is important for the lateral stability of the knee. In contrast to the medial collateral ligament, the fibers are not attached to the meniscus. The tendon of the popliteus muscle passes deep to the ligament, separating it from the meniscus of the knee. The iliotibial band is a continuation of the tensor fasciae latae muscle, and it attaches to the lateral condyle of the tibia (Fig. 14-17). This band helps keep the knee extended during standing and is important for lateral stability of the knee.

Procedure

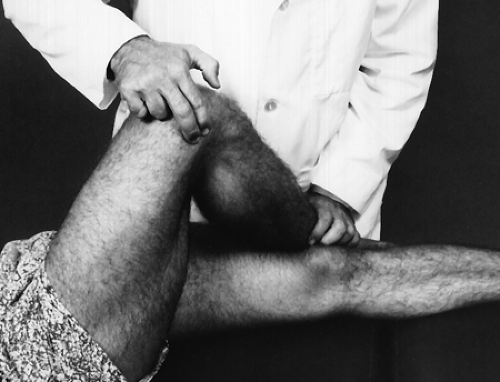

With the patient either supine or sitting, instruct the patient to cross one leg over the other (Fig. 14-18). With your index and middle finger, palpate the lateral collateral ligament of the top leg from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula. Note any pain, tenderness, or defect. Pain and tenderness may indicate a sprain or calcification of the ligament. A defect secondary to trauma may indicate a tear or avulsion of the lateral collateral ligament. Next, palpate the entire length of the iliotibial band from halfway between the hip and knee on the lateral aspect to the lateral condyle of the tibia (Fig. 14-19). Note any pain, tenderness, or defects of the iliotibial band. Pain and tenderness may indicate a strain of the band. A defect secondary to trauma may indicate a tear or avulsion of the band from the lateral condyle of the tibia.

Posterior Aspect

Descriptive Anatomy

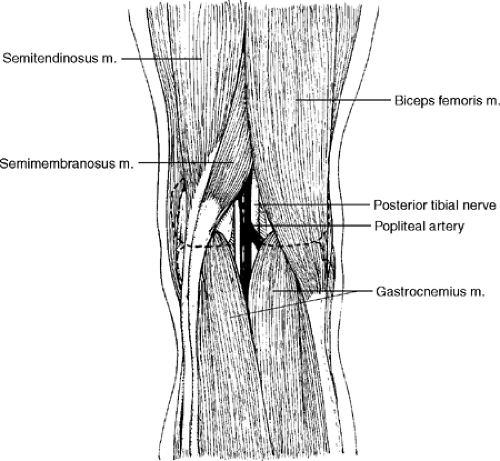

The popliteal fossa is surrounded by the biceps femoris tendon on the superior lateral border and the tendons of the semimembranosus and semitendinosus on the superior medial border. The inferior borders are bounded by the two heads of the gastrocnemius muscles. The posterior tibial nerve, popliteal artery, and popliteal vein cross the popliteal fossa (Fig. 14-20).

Procedure

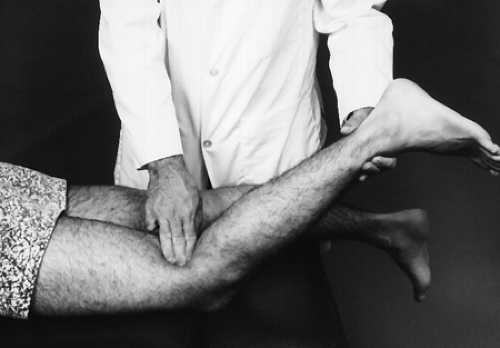

With the knee slightly flexed, palpate the popliteal fossa for swelling or tenderness (Fig. 14-21). These signs may indicate Baker’s cyst, a pressure diverticulum of the synovial sac protruding through the joint capsule of the knee. Next, palpate the biceps femoris tendon (Fig. 14-22), semimembranosus tendon, semitendinosus tendon (Fig. 14-23), and both heads of the gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 14-24) for tenderness, swelling, and continuity. This tenderness and swelling may indicate a strain of the respective tendons or muscles. Loss of continuity may indicate an avulsion of the respective muscles or tendons.

Knee Range of Motion

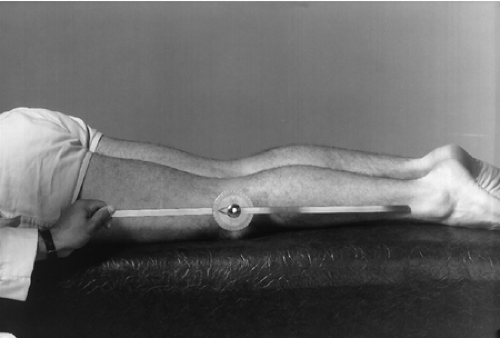

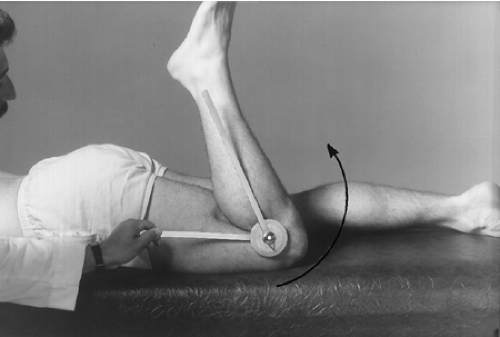

With the patient prone and the leg extended, place the goniometer in the sagittal plane with the center at the knee joint (Fig. 14-25). Instruct the patient to flex the leg as far as possible while following the leg with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 14-26).

Normal Range (2)

Normal range is 141° ± 6.5° or greater from the 0 or neutral position.

| Muscles | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|

| Biceps femoris | Sciatic |

| Semimembranosus | Sciatic |

| Semitendinosus | Sciatic |

| Gracilis | Obturator |

| Sartorius | Femoral |

| Popliteus | Tibial |

| Gastrocnemius | Tibial |

| Plantaris | Superior gluteal |

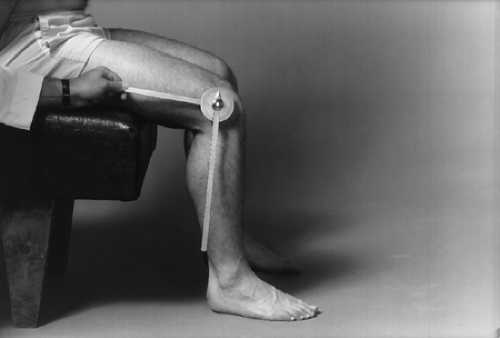

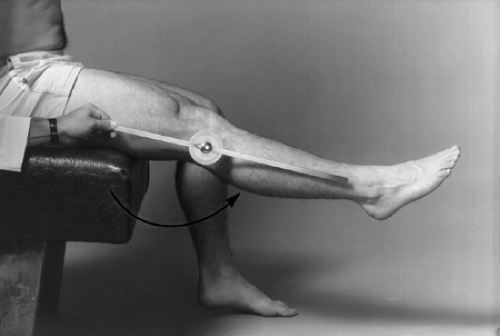

With the patient seated, foot on the floor, place the goniometer in the sagittal plane with the center at the knee (Fig. 14-27). Instruct the patient to extend the leg as far as possible while following the leg with one arm of the goniometer (Fig. 14-28). Note that this test starts with the leg in 90° of flexion and you want the knee to extend to the 0 or neutral position.

Normal Range (2)

Normal range is 0 ± 2°.

| Muscles | Nerve Supply |

|---|---|

| Rectus femoris | Femoral |

| Vastus medialis | Femoral |

| Vastus intermedius | Femoral |

| Vastus lateralis | Femoral |

Meniscus Instability

Clinical Description

The menisci are C-shaped disks of fibrocartilage that are interposed between the condyles of the femur and the tibia. The functions of the meniscus are many. Its primary function is load transmission or weight bearing, and the secondary function is shock absorption during gait. The menisci are also thought to contribute to joint stability and lubrication. Finally, because of the nerve endings in the anterior and posterior horns, proprioception provides a feedback mechanism for joint position.

A tear or loss of the menisci, either partial or complete, hinders their ability to function and predisposes the joint to degenerative changes. A twisting injury to the knee with the foot in a weight-bearing position is the most common injury to the meniscus. Because the outer 20% of the menisci have a vascular supply, peripheral injuries may heal. The inner 80% of the menisci are avascular, so inner meniscal injuries rarely heal.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Local medial or lateral joint pain

Limited knee range of motion

Crepitus upon movement

Joint effusion

Knee buckling

Pain on walking up and down stairs

Pain on squatting

Apley’s Compression Test (3)

|

Procedure

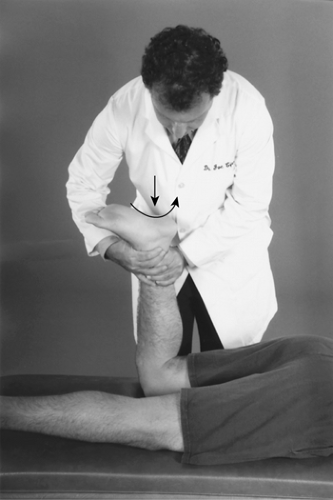

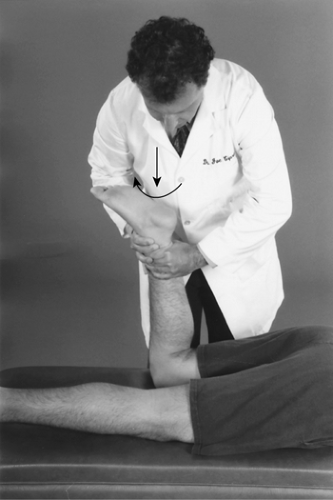

With the patient prone, flex the leg to 90°. Stabilize the patient’s thigh with your knee. Grasp the patient’s ankle and place downward pressure while you internally (Fig. 14-29) and externally (Fig. 14-30) rotate the leg.

Rationale

The menisci, which are asymmetric fibrocartilaginous disks, separate the tibial condyles from the femoral condyles. When the knee is flexed, the meniscus distorts to maintain the congruence between the tibial and femoral condyles. Flexion of the knee applies downward pressure with internal and external rotation stress to the already distorted meniscus. Pain or crepitus on either side of the knee indicates a meniscus injury on that side.

|

Procedure

With the patient supine, flex the leg (Fig. 14-31). Externally rotate the leg as you extend (Fig. 14-32); then internally rotate as you extend (Fig. 14-33).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree